Garnet Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Viscount Wolseley

|

|

|---|---|

Field Marshal Lord Wolseley

|

|

| 8th Commander-in-Chief of the British Army | |

| In office 1 November 1895 – 3 January 1901 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Prime Minister | Marquess of Salisbury |

| Preceded by | Prince George, Duke of Cambridge |

| Succeeded by | Lord Frederick Roberts |

| Governor of Transvaal | |

| In office 29 September 1879 – 27 April 1880 |

|

| Preceded by | Owen Lanyon |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished The Viscount Milner (1901) |

| Governor of the Gold Coast | |

| In office 2 October 1873 – 4 March 1874 |

|

| Preceded by | Robert William Harley |

| Succeeded by | James Maxwell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 June 1833 Golden Bridge House, Inchicore, Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 25 March 1913 (aged 79) Menton, France |

| Resting place | St. Paul's Cathedral, London |

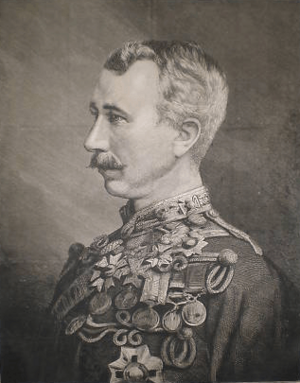

| Awards | Knight of the Order of St Patrick Member of the Order of Merit Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Volunteer Decoration Mentioned in Despatches Order of the Medjidie (Ottoman Empire) Order of Osmanieh (Ottoman Empire) Legion of Honour (France) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom Egypt |

| Branch/service | British Army |

| Years of service | 1852–1900 |

| Rank | Field Marshal |

| Commands | Commander-in-Chief of the Forces Commander-in-Chief, Ireland Adjutant-General to the Forces Quartermaster-General to the Forces |

| Battles/wars | Second Burmese War Crimean War American Civil War (observer) |

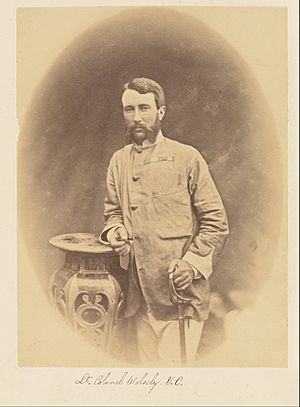

Field Marshal Garnet Joseph Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley (born June 4, 1833 – died March 25, 1913) was an important Anglo-Irish officer in the British Army. He became one of Britain's most respected generals. He achieved success in Canada, West Africa, and Egypt. He also played a key role in making the British Army more modern and efficient.

Wolseley is seen as one of the most famous war heroes of the British Empire during a time called New Imperialism. He fought in many places, including Burma, the Crimean War, and the Indian Mutiny. He also served in China, Canada, and various parts of Africa. His campaigns included the Ashanti War (1873–1874) and the Nile Expedition in Sudan (1884–85). From 1895 to 1900, Wolseley was the Commander-in-Chief of the Forces. He was known for being very organized. This led to the saying "everything's all Sir Garnet," which meant "everything is in order."

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Starting His Military Career

- Fighting in the Crimean War

- Indian Rebellion of 1857

- American Civil War and Canadian Service

- Army Reforms

- Ashanti Campaign

- Service in Natal, Cyprus, and South Africa

- Egypt, the Nile Expedition, and Commander-in-Chief

- Channel Tunnel Opposition

- Personal Life and Death

- Legacy and Recognition

- See also

Early Life and Education

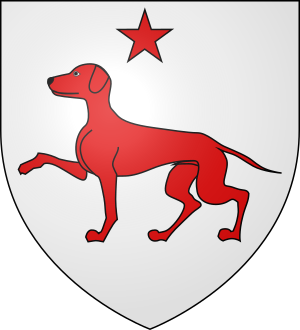

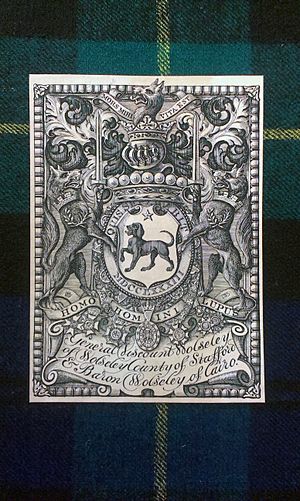

Garnet Wolseley was born in Dublin, Ireland. He came from an important Anglo-Irish family. His father, Major Garnet Joseph Wolseley, was an army officer. His mother was Frances Anne Wolseley. The Wolseley family had a long history in Staffordshire, England. Garnet was the oldest of seven children.

His father died in 1840 when Garnet was only seven. This left his mother and seven children with little money. Unlike other boys from similar families, Garnet did not go to famous schools like Harrow or Eton. Instead, he went to a local school in Dublin. At 14, he had to leave school to work in a surveyor's office. This job helped him earn money and continue studying math and geography.

Starting His Military Career

Wolseley first thought about becoming a church minister. But he needed money to do this, which he didn't have. So, he decided to join the Army. He couldn't afford to go to a military college or buy a rank. He wrote to Field Marshal The Duke of Wellington for help. Wellington was then the Commander-in-Chief of the Forces.

Wellington promised to help when Wolseley turned 16. However, he seemed to forget. Wolseley wrote again at 17, but got no reply. His mother then wrote to the Duke. Because of his father's service, 18-year-old Wolseley was made an ensign (a junior officer) in the 12th Foot on March 12, 1852.

Just one month later, he moved to the 80th Foot. He served with them in the Second Anglo-Burmese War. He was badly wounded in his left thigh during an attack on Donabyu in March 1853. He was praised for his bravery. He was promoted to lieutenant and sent home to recover. He later became a captain in December 1854.

Fighting in the Crimean War

Wolseley joined his regiment in the Crimea in December 1854. He was chosen to work as an assistant engineer with the Royal Engineers. He served during the Siege of Sevastopol. He was wounded twice during the siege. In August 1855, he lost an eye.

After Sevastopol fell, Wolseley helped with moving troops and supplies. He was one of the last British soldiers to leave Crimea in July 1856. For his service, he was praised twice. He received a war medal and honors from France and Turkey.

In March 1857, he went with his regiment to China for the Second Opium War. But their ship was wrecked. The troops were saved and sent to Calcutta because of the Indian Mutiny.

Indian Rebellion of 1857

Wolseley showed great courage during the relief of Lucknow in November 1857. He also helped defend the Alambagh position. He took part in many battles there. In March, he helped capture Lucknow. He then became a deputy-assistant quartermaster-general. He was involved in all the operations of the campaign. This included battles like Bari, Nawabganj, and the capture of Faizabad.

In late 1858 and early 1859, he helped put down the rebellion completely. He was often praised for his service. He received the Mutiny medal. He was promoted to brevet major in March 1858 and brevet lieutenant-colonel in April 1859.

Wolseley continued to serve in India. When his commander, Sir Hope Grant, was sent to China, Wolseley went with him. He was part of the British and French expedition in 1860. He was present at several battles, including the storming of the Taku Forts. He also saw the entry into Peking and the destruction of the Old Summer Palace. He was praised again and received another medal. When he returned home, he wrote a book called Narrative of the War with China. He became a major in February 1861.

American Civil War and Canadian Service

In 1862, Wolseley took a break from his military duties. He traveled to America to observe the American Civil War. He met with Southern supporters in Maryland. They helped him travel into Virginia. There, he met famous Confederate generals like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. He also wrote about Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest.

In November 1861, Wolseley was sent to Canada. This was because of the Trent Affair, a diplomatic incident. After the American Civil War ended, Wolseley returned to Canada. He became a brevet colonel in June 1865. He helped defend Canada from Fenian raids coming from the United States.

In 1869, he published his book Soldiers' Pocket Book for Field Service. This book became very popular and was reprinted many times. In 1870, he successfully led the Red River Expedition. This expedition helped establish Canadian control over the North-West Territories and Manitoba. The journey to Fort Garry (now Winnipeg) was very difficult. It involved traveling over 600 miles through rivers and lakes. Wolseley's excellent planning earned him high honors. He was made a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George.

Army Reforms

In 1871, Wolseley became an assistant adjutant-general at the War Office. He worked to support the Cardwell reforms. These reforms aimed to make the British Army stronger. They wanted to build up army reserves. This meant soldiers would serve part of their time in the army and then join the reserves. The reforms also brought local militia groups into the new army structure.

Many senior military leaders, including the Duke of Cambridge, opposed these changes. But Wolseley strongly fought for them. He continued to push for these reforms even after the laws were passed. He believed that volunteer reserves were very important. He later said that all army reforms since 1860 had first been suggested by volunteers.

Ashanti Campaign

On October 2, 1873, Wolseley became Governor of Sierra Leone and the Gold Coast. This meant he was in charge of British territories in West Africa. In this role, he led an expedition against the Ashanti Empire. Wolseley made all his plans before his troops arrived in January 1874.

At the Battle of Amoaful on January 31, Wolseley's forces defeated a larger Ashanti army. They fought for four hours through thick bush. After five days of fighting, the British entered the Ashanti capital, Kumasi, and burned it. Wolseley finished the campaign in just two months. He sent his troops home before the unhealthy season began. This campaign made him very famous in Britain.

He received thanks from Parliament and a large sum of money. He was promoted to brevet major-general in April 1874. He also received several high honors, including the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George. The City of London gave him the freedom of the city and a sword of honor. He also received honorary degrees from Oxford and Cambridge universities.

Service in Natal, Cyprus, and South Africa

After returning home, he became inspector-general of Auxiliary Forces. He worked hard to build up strong volunteer reserve forces. He faced opposition from senior military figures. But he strongly argued for his ideas, even threatening to resign. He remained a strong supporter of the volunteer reserves throughout his life.

Soon after, he was sent to Natal (in South Africa) as governor and general-commanding in February 1875. This was due to unrest among the local people.

Wolseley joined the Council of India in November 1876. He was promoted to major-general in October 1877 and brevet lieutenant-general in March 1878. On July 12, 1878, he became the first High Commissioner to Cyprus, a new British possession.

The next year, he was sent to South Africa. He took command of the forces in the Zulu War. He also became governor of Natal and the Transvaal. When he arrived in July, the Zulu War was almost over. After making a temporary peace, he went to the Transvaal. While in South Africa, he was promoted to brevet general in June 1879. He reorganized the government there and defeated King Sekhukhune of the Bapedi. He returned to London in May 1880. For his service, he received the South Africa Medal and was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath.

He was then appointed Quartermaster-General to the Forces in July 1880. He found that many people still resisted the short service system for soldiers. He used his growing fame to fight for the Cardwell reforms. He gave a speech where he said that an army with long-serving soldiers "totally disappeared in a few months under the walls of Sevastopol."

Egypt, the Nile Expedition, and Commander-in-Chief

On April 1, 1882, Wolseley became Adjutant-General to the Forces. In August, he was given command of British forces in Egypt. His mission was to stop the Urabi Revolt. He quickly took control of the Suez Canal. He then landed his troops at Ismailia. After a very short campaign, he completely defeated Urabi Pasha at the Battle of Tel el-Kebir. This ended the rebellion.

For his success, he was promoted to general in November. He was also made a Baron Wolseley in the peerage. He received thanks from Parliament and the Egypt Medal. The Khedive (ruler) of Egypt gave him the Order of Osmanieh.

On September 1, 1884, Wolseley was again called away from his duties. He was to command the Nile Expedition. This expedition aimed to rescue General Gordon and his besieged forces in Khartoum. Wolseley's plan was to travel by boat up the Nile River. Then, they would cross the desert to Khartoum. However, the expedition arrived too late. Khartoum had already been captured, and General Gordon was dead.

In 1885, there were problems with Imperial Russia over the Panjdeh Incident. This led to the withdrawal of the expedition. For his service, he received more honors and was made Viscount Wolseley in September 1885. The Queen invited his family to live at the grand Ranger's House in Greenwich in 1888.

Wolseley continued as Adjutant-General to the Forces until 1890. He then became Commander-in-Chief, Ireland. He was promoted to field marshal on May 26, 1894. The Conservative government appointed him to replace the Duke of Cambridge. He became Commander-in-Chief of the Forces on November 1, 1895. This was a position he was well-suited for due to his experience. However, his powers were limited by new rules. After five years, he handed over command to Earl Roberts in January 1901. He also suffered a serious illness in 1897 and never fully recovered.

The large army needed for the start of the Second Boer War was mainly put together using the reserve system Wolseley had created. By using regular and volunteer reservists, Britain could send its largest army ever overseas. However, Wolseley was not happy with the new setup at the War Office. After a difficult period, he was removed from his responsibilities in late 1900. He later spoke about this in the House of Lords.

Lord Wolseley served as Gold Stick in Waiting for Queen Victoria. He took part in her funeral procession in February 1901. He also served King Edward during his coronation in August 1902.

Honors and Royal Appointments

In early 1901, King Edward asked Lord Wolseley to lead a special diplomatic mission. He was to announce the King's new role to the governments of Austria-Hungary, Romania, Serbia, the Ottoman Empire, and Greece. During his visit to Constantinople, the Sultan gave him the Order of Osmanieh.

He was one of the first people to receive the Order of Merit in 1902. He also received the Volunteer Officers' Decoration for his service with the Volunteer Force. He held several honorary colonel positions in different regiments.

Channel Tunnel Opposition

Wolseley was strongly against building a Channel Tunnel between England and France. He told a parliamentary group that the tunnel could be "disastrous for England." He worried that a continental army could easily seize the tunnel exit by surprise. People suggested ways to address his concerns. For example, the tunnel could loop out from the White Cliffs of Dover so the Royal Navy could bomb it if needed. For various reasons, it took over 100 years before a permanent link was made.

Personal Life and Death

Wolseley married Louisa Erskine in 1867. They had one child, a daughter named Frances (1872–1936). Frances became an author and founded a college for lady gardeners. She inherited her father's title, but it ended after her death because she had no children.

In his later years, Lord and Lady Wolseley lived in an apartment at Hampton Court Palace. He and his wife were spending the winter in Menton, France. He became ill with the flu and died on March 26, 1913.

He was buried on March 31, 1913, in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral in London. The band of the Royal Irish Regiment played music at his funeral. He was the first Colonel-in-Chief of this regiment.

Legacy and Recognition

There is a statue of Wolseley on horseback at Horse Guards Parade in London. It was created by Sir William Goscombe John R.A. and put up in 1920.

Wolseley Barracks in London, Ontario, Canada, is a military base named after him. It was built in 1886. It has always housed parts of the Canadian Army. Today, it is home to the Royal Canadian Regiment Museum. The white pith helmet worn by many Canadian regiments is called a Wolseley helmet. Wolseley is also the name of a senior boys' house at the Duke of York's Royal Military School.

A memorial tablet for Field Marshal Lord Wolseley is at St Michael and All Angels Church in Colwich, Staffordshire. This church is near the ancestral home of the Wolseley family.

W. S. Gilbert, who wrote the famous Gilbert and Sullivan operettas, based the character of Major-General Stanley in The Pirates of Penzance on Wolseley. In another operetta, Patience, Colonel Calverley praises Wolseley's skill.

The areas of Wolseley in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, and Wolseley, Saskatchewan, Canada, are named after him. The town of Wolseley, Western Cape, South Africa, is also named after him. It was founded in 1875.

The Sir Garnet pub in Norwich, England, is named after Field Marshal Lord Wolseley. It opened around 1861 and took his name in 1874.

In Ghana, Wolseley is known as "Sargrenti." He is shown as a villain in the 2014 novel The Boy Who Spat in Sargrenti's Eye. This book tells a fictional story of the Anglo-Ashanti war from the view of an Ashanti boy.

Wolseley's uniforms, field marshal's baton, and souvenirs from his campaigns are kept at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Canada. He also collected items related to famous historical figures.

Because of his success and efficiency, the saying "all Sir Garnet" became popular. It means that everything is in good order and ready.

See also

In Spanish: Garnet Wolseley para niños

In Spanish: Garnet Wolseley para niños

- Royal Horse Guards

- British Cavalry

- British Army

- Essex Regiment