W. S. Gilbert facts for kids

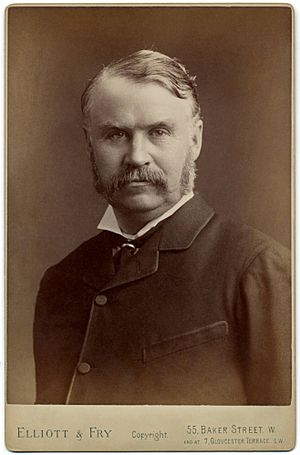

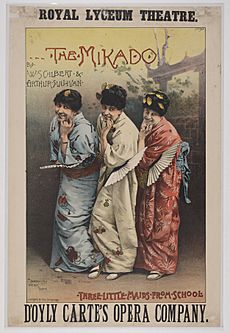

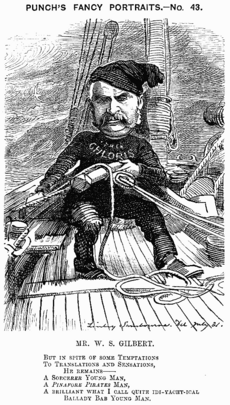

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert (born November 18, 1836 – died May 29, 1911) was an English writer and artist. He is most famous for working with the composer Arthur Sullivan. Together, they created fourteen funny operas, often called comic operas. Some of their most well-known works include H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, and The Mikado. The Mikado is one of the most performed musical shows ever!

For over a century, their works were performed all year round by the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company. This company was started by Gilbert, Sullivan, and their producer Richard D'Oyly Carte. These operas, known as Savoy Operas, are still very popular today in English-speaking countries and beyond.

Gilbert wrote more than 75 plays and opera stories (called libretti). He also wrote many short stories, poems, and songs, both funny and serious. After working as a government clerk and a lawyer, Gilbert started focusing on writing in the 1860s. He wrote light poems, including his Bab Ballads, short stories, and theatre reviews. He often drew pictures for Fun magazine.

He also began writing funny plays called burlesques. He developed a unique, upside-down style that became known as his "topsy-turvy" style. He was also known for directing plays in a very realistic way and was a strict theatre director. In the 1870s, Gilbert wrote 40 plays and libretti. This included his German Reed Entertainments, some serious plays, and his first five collaborations with Sullivan: Thespis, Trial by Jury, The Sorcerer, H.M.S. Pinafore, and The Pirates of Penzance. In the 1880s, Gilbert focused on the Savoy Operas, such as Patience, Iolanthe, The Mikado, The Yeomen of the Guard, and The Gondoliers.

In 1890, after a long and successful partnership, Gilbert had a big disagreement with Sullivan and Carte. This fight, known as the "carpet quarrel," was about money spent at the Savoy Theatre. Gilbert won the lawsuit, but it caused bad feelings among them. Gilbert and Sullivan did work together on two more operas, but they were not as successful as their earlier ones. In his later years, Gilbert wrote more plays and a few operas with other people. He retired with his wife Lucy and their adopted daughter, Nancy McIntosh, to a country home called Grim's Dyke. He was made a knight in 1907. Gilbert died from a heart attack while trying to save a young woman during a swimming lesson in the lake at his home.

Gilbert's plays inspired other famous writers like Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw. His comic operas with Sullivan helped shape American musical theatre, especially influencing writers for Broadway. According to The Cambridge History of English and American Literature, Gilbert's "skill with words and his mastery of rhythm made comic opera poetry better than it had ever been before, or since."

Contents

Gilbert's Early Life and Career

How Did Gilbert Start?

| "As soon as the judge said this, the poor person bent down, took off a heavy boot, and threw it at my head. This was her thanks for my great speech on her behalf! She also yelled many insults about my skills as a lawyer and my defense plan." |

| — My Maiden Brief

(Gilbert said this story was true about himself.) |

Gilbert was born in London at 17 Southampton Street, Strand. His father, also named William, was a naval surgeon for a short time. Later, he became a writer of novels and short stories, some of which his son illustrated. Gilbert's mother was Anne Mary Bye Morris. Gilbert's parents were not very warm, and he wasn't very close to them. After their marriage ended in 1876, his relationship with them, especially his mother, became even more difficult.

Gilbert had three younger sisters. Two were born outside England because the family traveled a lot. Jane Morris was born in Milan, Italy, in 1838. Mary Florence was born in Boulogne, France, in 1843. Anne Maude was born in 1845. The two younger sisters never married. Gilbert was called "Bab" as a baby. Later, he was called "Schwenck" after his great aunt and uncle.

As a child, Gilbert traveled to Italy in 1838 and then to France for two years with his parents. They finally settled back in London in 1847. He went to school in Boulogne, France, from age seven. He later wrote his diary in French so servants couldn't read it. He then attended Western Grammar School in Brompton, London, and later the Great Ealing School. There, he became the head student and wrote plays for school shows, also painting the scenery.

He then went to King's College London, finishing in 1856. He wanted to join the Royal Artillery as an officer. But the Crimean War ended, so fewer soldiers were needed. The only military job available to Gilbert was in a regular army unit. Instead, he joined the Civil Service. He worked as an assistant clerk in the Privy Council Office for four years and disliked it. In 1859, he joined the Militia, a part-time group for Britain's defense. He served until 1878, reaching the rank of captain.

In 1863, he received £300, which he used to leave the civil service. He then started a short career as a barrister (a type of lawyer). He had already started studying law at the Inner Temple. His law practice was not very successful, with only about five clients a year.

To earn more money from 1861 onwards, Gilbert wrote many things. He wrote stories, funny rants, strange drawings, and theatre reviews. Many reviews were parodies of the plays he was reviewing. He also wrote illustrated poems under the name "Bab" (his childhood nickname) for several funny magazines, mainly Fun. This magazine was started in 1861 by H. J. Byron. He also published in other papers like The Cornhill Magazine and London Society. Gilbert was also a London reporter for L'Invalide Russe and a drama critic for the Illustrated London Times. In the 1860s, he also wrote for Christmas annuals and other magazines. In 1870, The Observer newspaper sent him to France as a war reporter for the Franco-Prussian War.

His poems, with Gilbert's funny drawings, became very popular. They were collected and published as the Bab Ballads. He later used many of these poems as ideas for his plays and comic operas. Gilbert and his friends from Fun magazine, like Tom Robertson and Tom Hood, often met at clubs and cafes.

After a relationship in the mid-1860s with writer Annie Thomas, Gilbert married Lucy Agnes Turner (1847–1936). Gilbert and Lucy were very social in London and later at Grim's Dyke. They often hosted dinner parties and were invited to others' homes. The Gilberts had no children, but they had many pets, including some unusual ones.

Gilbert's First Plays

Gilbert wrote and directed several plays at school. But his first play produced professionally was Uncle Baby, which ran for seven weeks in 1863.

In 1865–66, Gilbert worked with Charles Millward on several pantomimes. One was called Hush-a-Bye, Baby, On the Tree Top (1866). Gilbert's first solo success came a few days after Hush-a-Bye Baby opened. His friend and mentor, Tom Robertson, was asked to write a pantomime. But he didn't think he could do it in two weeks. So, he suggested Gilbert instead.

Gilbert wrote Dulcamara, or the Little Duck and the Great Quack in just 10 days. It was a burlesque (a funny parody) of Gaetano Donizetti's opera L'elisir d'amore. It became very popular. This led to many more funny opera parodies, pantomimes, and farces by Gilbert. These plays were full of silly puns, which were common in burlesques then. But they also showed signs of the satire that would become a key part of Gilbert's later work.

Next came Gilbert's second-to-last opera parody, Robert the Devil. This was a burlesque of Giacomo Meyerbeer's opera, Robert le diable. It was part of a show that opened the Gaiety Theatre, London, in 1868. This play was Gilbert's biggest success so far. It ran for over 100 nights and was often brought back and played in other towns for three years.

In Victorian theatre, it was common for burlesques to make fun of serious and beautiful themes. However, Gilbert's burlesques were seen as more tasteful than others in London. Isaac Goldberg wrote that these plays "show how a playwright can start by making fun of opera and end by making opera out of fun." Gilbert began to move away from the burlesque style around 1869. He started writing plays with original stories and fewer puns. His first full-length comedy was An Old Score (1869).

German Reed Shows and Other Plays (Early 1870s)

When Gilbert started writing, theatre was not highly respected. Poorly translated French operettas and badly written, rude burlesques were common in London. As actress Jessie Bond described it, "the theatre had become a bad place for respectable British families." Bond helped create many roles in Gilbert and Sullivan operas. She was talking about how Gilbert helped improve Victorian theatre.

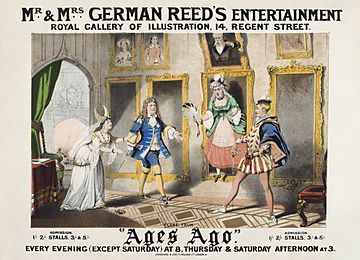

From 1869 to 1875, Gilbert worked with Thomas German Reed and his wife Priscilla. Their Gallery of Illustration aimed to make theatre more respectable by offering family-friendly shows in London. They were so successful that by 1885, Gilbert said that original British plays were suitable for a 15-year-old girl to watch. Three months before Gilbert's last burlesque opened, his first play for the Gallery of Illustration, No Cards, was produced. Gilbert created six musical shows for the German Reeds. Some had music by Thomas German Reed.

The small theatre of the German Reeds allowed Gilbert to quickly develop his own style. He had freedom to control all parts of the production, including sets, costumes, and directing. These works were a success. Gilbert's first big hit at the Gallery of Illustration, Ages Ago, opened in 1869. Ages Ago also started his seven-year collaboration with composer Frederic Clay, which produced four works. It was at a rehearsal for Ages Ago that Clay introduced Gilbert to his friend, Arthur Sullivan. The Bab Ballads and Gilbert's many early musical works gave him a lot of practice writing song lyrics even before he worked with Sullivan.

Many ideas from the German Reed Entertainments (and some from his earlier plays and Bab Ballads) were used again by Gilbert in the later Gilbert and Sullivan operas. These ideas include paintings coming to life (Ages Ago, used again in Ruddigore). Another idea was a deaf nursemaid accidentally binding a respectable man's son to a "pirate" instead of a "pilot" (Our Island Home, 1870, used again in The Pirates of Penzance). Also, a strong older lady who is "an acquired taste" (Eyes and No Eyes, 1875, used again in The Mikado).

During this time, Gilbert perfected his 'topsy-turvy' style. In this style, the humor comes from setting up a ridiculous idea and then showing its logical, but absurd, results. Director Mike Leigh describes the "Gilbertian" style: Gilbert "constantly challenges what we expect. First, in the story, he makes strange things happen and turns the world upside down. For example, the judge marries the plaintiff, and soldiers become artists. Almost every opera is solved by cleverly changing the rules. His genius is to mix opposites smoothly, blending the unreal with the real, and funny drawings with natural behavior. In other words, he tells a completely outrageous story in a very serious way."

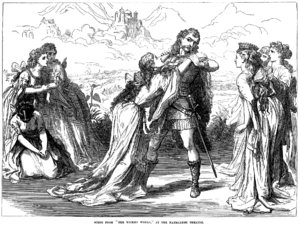

At the same time, Gilbert created several "fairy comedies" at the Haymarket Theatre. These plays were based on characters revealing their true selves when influenced by magic or supernatural events. The first was The Palace of Truth (1870). In 1871, with Pygmalion and Galatea, Gilbert had his biggest hit yet. He produced seven plays that year. These plays, and later ones like The Wicked World (1873), Sweethearts (1874), and Broken Hearts (1875), showed that Gilbert could write more than just burlesques. They earned him artistic respect and proved he was a versatile writer, comfortable with human drama as well as funny humor. The success of these plays, especially Pygmalion and Galatea, gave Gilbert a good reputation. This was important for his later work with a respected musician like Sullivan.

| "It is very important for this play to succeed that it is acted with perfect seriousness and gravity throughout. There should be no over-the-top costumes, makeup, or actions. The characters should all seem to believe, completely, in the truth of their words and actions. As soon as the actors show they know their words are silly, the play starts to get boring." |

| — From the Preface to Engaged |

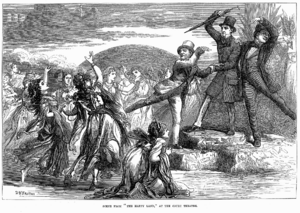

During this time, Gilbert also pushed the limits of how much satire could be used in theatre. He worked with Gilbert Arthur à Beckett on The Happy Land (1873). This was a political satire, partly making fun of his own play The Wicked World. It was briefly banned because it made fun of Gladstone and his government ministers. Similarly, The Realm of Joy (1873) was set in the lobby of a theatre showing a scandalous play (implied to be The Happy Land). It had many jokes at the expense of the Lord Chamberlain (who was called the "Lord High Disinfectant" in the play). These works were early examples of "problem plays" like those by Shaw and Ibsen.

Gilbert as a Director

Once he became well-known, Gilbert directed his own plays and operas. He had strong ideas about how they should be performed. He was greatly influenced by new ideas in "stagecraft" (now called stage direction) from playwrights like James Planché and especially Tom Robertson. Gilbert watched Robertson's rehearsals to learn directing firsthand. He started using these ideas in his early plays.

He wanted acting, settings, costumes, and movement to be realistic, even if the play's story itself was not. He avoided actors directly talking to the audience. He insisted that characters should never seem aware of how silly they were. Instead, they should act as if their actions were completely normal. Gilbert even wrote a romantic comedy in a "naturalist" style, Sweethearts, as a tribute to Robertson.

In Gilbert's 1874 play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, the character Hamlet explains Gilbert's idea of comic acting. He says, "I believe there is no funnier person than a boastful hero who speaks his foolishness so seriously that his listeners believe he doesn't see how absurd it is." Robertson "taught Gilbert about disciplined rehearsals and about having a unified style for the whole show – directing, design, music, and acting." Like Robertson, Gilbert demanded discipline from his actors. He required them to know their lines perfectly, speak them clearly, and follow his stage directions. These were new ideas for many actors at the time. A major change was replacing the main "star" actor with a disciplined group of actors. This made the director much more important in the theatre. "There's no doubt that Gilbert was a good director. He could get natural, clear performances from his actors, which fit Gilbert's need for outrageousness delivered seriously."

Gilbert prepared very carefully for each new work. He made models of the stage, actors, and set pieces. He planned every action and detail beforehand. He would not work with actors who questioned his authority. George Grossmith wrote that, at least sometimes, "Mr. Gilbert is a complete dictator. He insists that his words be spoken exactly as he says, even down to the tone of voice. He would stand on stage next to the actor or actress and repeat the words with the right actions again and again until they were done as he wanted." Even during long runs and revivals, Gilbert closely watched the performances. He made sure actors didn't add, remove, or change lines without permission. Gilbert was famous for showing the actions himself, even when he was older. Gilbert himself sometimes went on stage. He played the Associate in Trial by Jury several times. He also filled in for an injured actor in a charity show of Broken Hearts. He also performed in charity shows of his one-act plays, like King Claudius in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.

Working with Sullivan

First Works Together and Other Projects

In 1871, John Hollingshead asked Gilbert to work with Sullivan on a Christmas show, Thespis, or The Gods Grown Old, at the Gaiety Theatre. Thespis ran longer than five of the nine other holiday shows in 1871. Its run was extended beyond a normal show length at the Gaiety. However, nothing more came of it then, and Gilbert and Sullivan went their separate ways. Gilbert worked again with Clay on Happy Arcadia (1872) and with Alfred Cellier on Topsyturveydom (1874). He also wrote several farces, opera stories, extravaganzas, fairy comedies, adaptations from novels, translations from French, and the dramas mentioned earlier. Also in 1874, he published his last piece for Fun magazine, "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern", after a three-year break. He then quit because he didn't like the new owner's other publishing interests.

It would be almost four years after Thespis before the two men worked together again. In 1868, Gilbert had published a short funny sketch in Fun magazine called "Trial by Jury: An Operetta." In 1873, the theatre manager, Carl Rosa, asked Gilbert to write a work for his planned 1874 season. Gilbert expanded "Trial" into a one-act opera story. However, Rosa's wife Euphrosyne Parepa-Rosa, a childhood friend of Gilbert's, died in 1874. So Rosa dropped the project. Later in 1874, Gilbert offered the story to Richard D'Oyly Carte, but Carte couldn't use it then.

By early 1875, Carte was managing the Royalty Theatre. He needed a short opera to play after Offenbach's La Périchole. He contacted Gilbert, asked about the piece, and suggested Sullivan to write the music. Sullivan was excited, and Trial by Jury was composed in a few weeks. The short piece was a huge hit. It ran longer than La Périchole and was brought back at another theatre.

Gilbert continued his effort to gain respect for his profession. One thing that might have held playwrights back was that plays were not published in a nice format for a "gentleman's library." At the time, they were usually published cheaply for actors, not for people to read at home. To help fix this, Gilbert arranged in late 1875 for publishers Chatto and Windus to print a volume of his plays. It was designed to appeal to general readers, with a nice binding and clear print. It contained Gilbert's most respectable plays, including his serious works, but cleverly ended with Trial by Jury.

After Trial by Jury was successful, there were talks about bringing back Thespis. But Gilbert and Sullivan couldn't agree on terms with Carte and his supporters. The music for Thespis was never published, and most of it is now lost. It took some time for Carte to get money for another Gilbert and Sullivan opera. During this time, Gilbert produced several works, including Tom Cobb (1875), Eyes and No Eyes (1875, his last German Reed Entertainment), and Princess Toto (1876). This was his last and most ambitious work with Clay. It was a three-act comic opera with a full orchestra, unlike his earlier shorter works with less music. Gilbert also wrote two serious plays during this time, Broken Hearts (1875) and Dan'l Druce, Blacksmith (1876).

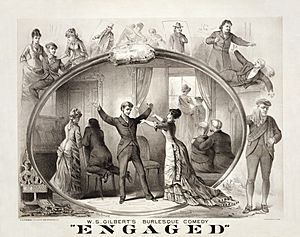

Also during this period, Gilbert wrote Engaged (1877). This play inspired Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest. Engaged is a parody of romantic drama. It uses the "topsy-turvy" satiric style found in many of Gilbert's Bab Ballads and the Savoy Operas. In the play, one character promises his love, using very poetic language, to every single woman in the story. The story shows some "innocent" Scottish villagers who make money by causing train crashes and then charging passengers for help. It also shows how people easily give up romance for money. A New York Times reviewer wrote in 1879, "Mr Gilbert, in his best work, has always shown a tendency to present unlikely situations from a likely point of view. In that sense, he can claim to be original. Luckily, this skill is supported by a truly poetic imagination. In [Engaged] the author lets his humor run wild. The result, though very temporary, is a very amusing mix of characters – or caricatures – and mock-heroic events." Engaged is still performed today by both professional and amateur groups.

The Most Successful Years Together

Carte finally put together a group of investors in 1877. They formed the Comedy Opera Company to create new English comic operas. They started with a third collaboration between Gilbert and Sullivan, The Sorcerer, in November 1877. This play was a moderate success. H.M.S. Pinafore followed in May 1878. Despite a slow start, mainly because of a very hot summer, Pinafore became extremely popular by autumn.

After a disagreement with Carte about how profits were shared, the other Comedy Opera Company partners hired toughs. One night, they tried to storm the theatre to steal the sets and costumes. They wanted to put on their own show. But stagehands and others loyal to Carte fought them off. Carte continued as the sole manager of the newly named D'Oyly Carte Opera Company. Pinafore was so successful that over a hundred unauthorized productions appeared in America alone. Gilbert, Sullivan, and Carte tried for many years to control the American performance rights for their operas, but they were not successful.

For the next ten years, the Savoy Operas (named after the theatre Carte later built for them) were Gilbert's main focus. The successful comic operas with Sullivan continued to appear every year or two. Several of them were among the longest-running shows in musical theatre history up to that point. After Pinafore came The Pirates of Penzance (1879), Patience (1881), Iolanthe (1882), Princess Ida (1884, based on Gilbert's earlier play, The Princess), The Mikado (1885), Ruddigore (1887), The Yeomen of the Guard (1888), and The Gondoliers (1889).

Gilbert not only directed and managed all parts of the production for these works, but he also designed the costumes himself for Patience, Iolanthe, Princess Ida, and Ruddigore. He insisted on accurate and real-looking sets and costumes. This helped to make his absurd characters and situations feel more grounded and believable.

During this time, Gilbert and Sullivan also worked together on another major piece, the oratorio The Martyr of Antioch. It premiered at the Leeds music festival in October 1880. Gilbert adapted the original long poem by Henry Hart Milman into a story suitable for the music, and it includes some of his own writing. During this period, Gilbert also occasionally wrote plays to be performed elsewhere. These included both serious dramas (like The Ne'er-Do-Weel, 1878; and Gretchen, 1879) and humorous works (like Foggerty's Fairy, 1881). However, he no longer needed to write many plays each year, as he had before. In fact, during the more than nine years between The Pirates of Penzance and The Gondoliers, he wrote only three plays outside of his partnership with Sullivan. Only one of these, Comedy and Tragedy, was successful. Although Comedy and Tragedy had a short run because the lead actress refused to perform during Holy Week, the play was regularly revived.

In 1878, Gilbert achieved a lifelong dream: to play Harlequin. He did this at the Gaiety Theatre as part of an amateur charity production of The Forty Thieves, which he partly wrote himself. Gilbert practiced Harlequin's special dancing with his friend John D'Auban, who had arranged dances for some of his plays and would choreograph most of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas. Producer John Hollingshead later remembered, "the best part of the performance was the very serious and determined Harlequin played by W. S. Gilbert. It gave me an idea of what Oliver Cromwell would have made of the character." Another cast member recalled that Gilbert was tirelessly enthusiastic about the show. He often invited the cast to his home for dinner and extra rehearsals. "It would have been difficult, if not impossible, to find a more pleasant, kind, or agreeable companion than he was." In 1882, Gilbert had a telephone installed in his home and at the Savoy Theatre's prompt desk. This allowed him to monitor performances and rehearsals from his home study. Gilbert had mentioned the new technology in Pinafore in 1878, only two years after the device was invented and before London even had telephone service.

The "Carpet Quarrel" and End of Their Work Together

Gilbert's working relationship with Sullivan sometimes became difficult, especially during their later operas. This was partly because each man felt he was giving up his own work for the other's. It was also due to their very different personalities. Gilbert was often argumentative and easily offended, though he could also be incredibly kind. Sullivan, on the other hand, avoided conflict. Gilbert filled his opera stories with "topsy-turvy" situations where the normal social order was turned upside down. After a while, these topics often clashed with Sullivan's desire for realism and emotional depth in his music. Also, Gilbert's political satire often made fun of privileged people, while Sullivan enjoyed socializing with wealthy and titled friends.

Throughout their work together, Gilbert and Sullivan disagreed several times about what topic to choose for an opera. After both Princess Ida and Ruddigore, which were less successful than their other seven operas from H.M.S. Pinafore to The Gondoliers, Sullivan asked to leave the partnership. He said he found Gilbert's plots repetitive and that the operas were not artistically satisfying to him. While the two artists worked out their differences, Carte kept the Savoy Theatre open by showing revivals of their earlier works. Each time, after a few months' break, Gilbert would write an opera story that met Sullivan's objections, and their partnership continued successfully.

However, in April 1890, during the run of The Gondoliers, Gilbert challenged Carte about the production costs. Among other things Gilbert disagreed with, Carte had charged the cost of a new carpet for the Savoy Theatre lobby to their partnership. Gilbert believed this was a maintenance cost that Carte alone should pay. Gilbert confronted Carte, who refused to change the accounts. Gilbert stormed out and wrote to Sullivan that "I left him saying that it was a mistake to destroy the ladder by which he had climbed." Helen Carte wrote that Gilbert had spoken to Carte "in a way that I would not have thought you would use to a disobedient servant."

Gilbert filed a lawsuit. After The Gondoliers closed in 1891, he took back the rights to perform his opera stories, vowing to write no more operas for the Savoy. Gilbert next wrote The Mountebanks with Alfred Cellier and the unsuccessful Haste to the Wedding with George Grossmith. Sullivan wrote Haddon Hall with Sydney Grundy. Gilbert eventually won the lawsuit and felt he was right, but his actions and words had hurt his partners.

Nevertheless, their partnership had been so profitable that, after the financial failure of the Royal English Opera House, Carte and his wife tried to bring the writer and composer back together.

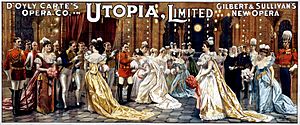

In 1891, after many failed attempts to make up, Tom Chappell, the music publisher for the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, stepped in to help. He managed to bring two of his most profitable artists together within two weeks. This resulted in two more operas: Utopia, Limited (1893) and The Grand Duke (1896). Gilbert also offered a third opera story to Sullivan (His Excellency, 1894). But Gilbert insisted on casting Nancy McIntosh, his protégée from Utopia, which led to Sullivan refusing. Utopia, about trying to make a South Pacific island kingdom more "English," was only a moderate success. The Grand Duke, where a theatre group takes political control of a grand duchy through a "statutory duel" and a conspiracy, was a complete failure. After that, their partnership ended for good. Sullivan continued to compose comic operas with other writers but died four years later. In 1904, Gilbert wrote, "...Savoy opera ended with the sad death of my talented partner, Sir Arthur Sullivan. When that happened, I saw no one I felt I could work with successfully, so I stopped writing opera stories."

Gilbert's Later Years

Gilbert built the Garrick Theatre in 1889. The Gilberts moved to Grim's Dyke in Harrow in 1890. He bought it from Robert Heriot. In 1891, Gilbert was appointed a Justice of the Peace for Middlesex. After casting Nancy McIntosh in Utopia, Limited, he and his wife grew fond of her. She eventually became like an unofficially adopted daughter, moving to Grim's Dyke to live with them. She continued living there even after Gilbert died, until Lady Gilbert's death in 1936. A statue of Charles II, carved in 1681, was moved in 1875 from Soho Square to an island in the lake at Grim's Dyke. It remained there when Gilbert bought the property. At Lady Gilbert's request, it was returned to Soho Square in 1938.

Although Gilbert announced he was retiring from theatre after the short run of his last work with Sullivan, The Grand Duke (1896), and the poor reception of his 1897 play The Fortune Hunter, he produced at least three more plays in the last twelve years of his life. This included an unsuccessful opera, Fallen Fairies (1909), with Edward German. Gilbert also continued to oversee the various revivals of his works by the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, including its London Repertory seasons from 1906–09. His last play, The Hooligan, produced just four months before his death, is about a young criminal in a prison cell. Like some of his earlier work, the play shows "his belief that upbringing, rather than natural traits, often explained criminal behavior." This serious and powerful play became one of Gilbert's most successful dramas. Experts believe that in his last months, Gilbert was developing a new style, a "mix of irony, social themes, and gritty realism," to replace his old "Gilbertianism" which he had grown tired of. In these last years, Gilbert also wrote children's book versions of H.M.S. Pinafore and The Mikado, sometimes adding background details not found in the original opera stories.

Gilbert was made a knight on July 15, 1907, for his contributions to drama. Sullivan had been knighted for his music almost 25 years earlier, in 1883. However, Gilbert was the first British writer ever to receive a knighthood just for his plays. Earlier playwrights who were knights, like Sir William Davenant and Sir John Vanbrugh, were knighted for political or other services.

On May 29, 1911, Gilbert was about to give a swimming lesson to two young women, Winifred Isabel Emery (born 1890) and 17-year-old Ruby Preece, in the lake at his home, Grim's Dyke. Ruby Preece got into trouble and called for help. Gilbert dived in to save her but had a heart attack in the middle of the lake and died at age 74. He was cremated at Golders Green, and his ashes were buried at St. John's Church, Stanmore. The inscription on Gilbert's memorial on the south wall of the Thames Embankment in London reads: "His Foe was Folly, and his Weapon Wit." There is also a memorial plaque at All Saints' Church, Harrow Weald.

Gilbert's Personality

Gilbert was known for being sometimes difficult. He knew people thought this about him. He claimed that the song "If you give me your attention" from Princess Ida, which is about a misanthrope (someone who dislikes people), was a funny reference to himself. He said: "I thought it my duty to live up to my reputation." However, many people have defended him, often mentioning his generosity.

The journalist Frank M. Boyd wrote: "Gilbert was a man of very strong feelings. He could be very kind and generous, but also very harsh and critical. He was quick to anger, but also quick to forgive. He was a man of great talent and great integrity."

Jessie Bond wrote that Gilbert "was quick-tempered, often unreasonable, and he could not stand to be stopped. But I cannot understand how anyone could call him unfriendly." George Grossmith wrote to The Daily Telegraph that, although Gilbert had been called a dictator at rehearsals, "That was really just how he acted when he was directing rehearsals. In truth, he was a generous, kind, true gentleman, and I use the word in its purest and original meaning."

Besides his occasional creative disagreements with Sullivan, and their eventual split, Gilbert's temper sometimes caused him to lose friendships. For example, he argued with his old colleague C. H. Workman over the firing of Nancy McIntosh from the production of Fallen Fairies. He also argued with actress Henrietta Hodson. His friendship with theatre critic Clement Scott also turned sour.

However, Gilbert could be incredibly kind. For instance, during Scott's final illness in 1904, Gilbert donated to a fund for him. He visited almost every day and helped Scott's wife, even though they hadn't been friendly for the previous sixteen years. Similarly, Gilbert had written several plays for the comic actor Ned Sothern. However, Sothern died before he could perform the last of these, Foggerty's Fairy. Gilbert bought the play back from Sothern's grateful widow.

Gilbert's niece Mary Carter stated, "he loved children very much and never missed a chance to make them happy... [He was] the kindest and most human of uncles." Letters between Gilbert and Muriel Barnby, the young daughter of Sir Joseph Barnby, show how much he enjoyed their playful exchange of letters. Grossmith quoted Gilbert as saying, "Deer-stalking would be a very fine sport if only the deer had guns."

Gilbert's Lasting Impact

Gilbert's legacy, besides building the Garrick Theatre and writing the Savoy Operas and other works that are still performed or in print nearly 150 years later, is perhaps most strongly felt today through his influence on American and British musical theatre. The new ideas in content and form that he and Sullivan developed, and Gilbert's ideas about acting and stage direction, directly influenced the growth of modern musicals throughout the 20th century. Gilbert's song lyrics used puns and complex rhyme schemes. They served as a model for 20th-century Broadway writers like P. G. Wodehouse, Cole Porter, Ira Gershwin, Lorenz Hart, and Oscar Hammerstein II.

Gilbert also had a notable impact on the English language. Well-known phrases like "A policeman's lot is not a happy one," "short, sharp shock," "What never? Well, hardly ever!," and "let the punishment fit the crime" all came from his writing. Also, people continue to write biographies about Gilbert's life and career. His work is not only performed but also often parodied, copied, quoted, and imitated in comedy shows, films, television, and other popular media.

See also

In Spanish: W. S. Gilbert para niños

In Spanish: W. S. Gilbert para niños

- W. S. Gilbert bibliography

- Cultural influence of Gilbert and Sullivan

- List of W. S. Gilbert dramatic works

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |