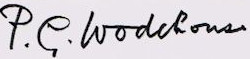

P. G. Wodehouse facts for kids

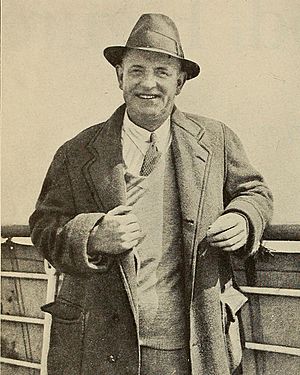

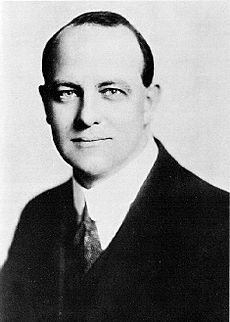

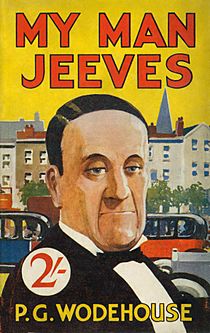

Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse (born October 15, 1881 – died February 14, 1975) was an English author. He was one of the most popular humorists of the 20th century. He created many famous characters. These include the silly Bertie Wooster and his clever valet, Jeeves. Other characters are the stylish Psmith, Lord Emsworth from Blandings Castle, the Oldest Member who tells golf stories, and Mr Mulliner who tells funny, exaggerated tales.

Wodehouse was born in Guildford, England. He was the third son of a British judge who worked in Hong Kong. He had a happy time as a teenager at Dulwich College and loved the school his whole life. After school, he worked at a bank but didn't like it. So, he started writing in his free time. His first books were mostly school stories, but he later began writing funny stories.

Most of Wodehouse's stories are set in England. However, he lived in the US for much of his life. He used New York and Hollywood as settings for some of his books and short stories. During and after the First World War, he wrote many Broadway musical comedies. He worked with Guy Bolton and Jerome Kern. These musicals were very important in how American musicals developed. In the 1930s, he wrote for MGM in Hollywood. In 1931, he gave an interview where he talked about how disorganized and wasteful the studios were. This caused a big stir. But in the same decade, his writing career became even more successful.

In 1934, Wodehouse moved to France for tax reasons. In 1940, German soldiers captured him at Le Touquet. He was held for almost a year. After he was released, he made six radio broadcasts from Berlin to the US. The US had not yet joined the war. These talks were funny and not about politics. But broadcasting on enemy radio made many people in Britain angry. He was even threatened with legal action. Wodehouse never went back to England. From 1947 until he died, he lived in the US. He became a citizen of both Britain and America in 1955. He died in 1975, at 93, in Southampton, New York. This was one month after he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE).

Wodehouse wrote a lot throughout his life. He published over ninety books, forty plays, and two hundred short stories between 1902 and 1974. He worked hard on his books, sometimes writing two or more at the same time. He would spend up to two years planning a story and writing a long outline. After that, he would write the actual story. When he was younger, he could write a novel in about three months. But when he got older, it took him around six months. He used old-fashioned slang, quotes from poets, and different writing styles. This made his writing sound like funny poetry or a musical comedy. Some critics thought his work was too lighthearted. But many famous people, including former British prime ministers and other writers, loved his books.

Contents

- Life and Career of P. G. Wodehouse

- Early Years and Family Life

- From Banking to Writing: 1900–1908

- Famous Characters Appear: 1908–1915

- Broadway Success: 1915–1919

- The 1920s: More Popular Stories

- Hollywood Adventures: 1929–1931

- Peak of Success: The 1930s

- Second World War: Being Held and Radio Talks

- After the War: Reactions and Investigations

- Living in America: 1946–1975

- Images for kids

- See also

Life and Career of P. G. Wodehouse

Early Years and Family Life

Wodehouse was born in Guildford, Surrey. He was the third son of Henry Ernest Wodehouse, a judge in Hong Kong. His mother was Eleanor. The Wodehouse family had a long history, going back to the 13th century. Eleanor was visiting her sister in Guildford when P. G. Wodehouse was born early.

He was christened at the Church of St Nicolas, Guildford. He was named after his godfather, Pelham von Donop. Wodehouse later wrote that he didn't really like his full name. His family and friends quickly started calling him "Plum."

When he was two, Wodehouse and his older brothers, Peveril and Armine, were sent to England. They were cared for by an English nanny named Emma Roper. Their parents returned to Hong Kong and didn't see their sons much. This was common for middle-class families living in colonies back then. Even though he didn't see his parents often, Wodehouse had a happy childhood. He later said that "it went like a breeze from start to finish." However, some people think that being away from his parents made him avoid showing too much emotion in his life and his stories.

In 1886, the brothers went to a small school in Croydon for three years. Then, because Peveril had a "weak chest," they moved to Elizabeth College on the island of Guernsey. In 1891, Wodehouse went to Malvern House Preparatory School in Kent. His father wanted him to join the Royal Navy, but his eyesight wasn't good enough. Wodehouse didn't like the school's strict rules and limited subjects. He later made fun of it in his novels, describing it as a "penitentiary" (like a prison).

During school holidays, the brothers stayed with various aunts and uncles. Wodehouse had twenty aunts, and they often appeared as strong, bossy aunts in his later novels. He also had fifteen uncles, four of whom were clergymen. These uncles inspired his funny, but friendly, characters of priests and bishops.

In 1894, at age twelve, Wodehouse was thrilled to join his brother Armine at Dulwich College. He felt completely at home there. Dulwich gave him "some continuity and a stable and ordered life." He loved being with his friends, and he was good at cricket, rugby, and boxing. He was a good student, though not always super hardworking. The headmaster, Arthur Herman Gilkes, was a big influence on him. Wodehouse's six years at Dulwich were some of the happiest of his life. He was also a good singer and helped edit the school magazine, The Alleynian. He loved the school his entire life.

From Banking to Writing: 1900–1908

Wodehouse expected to go to University of Oxford, like his brother. But his family's money situation got worse. His father's pension, paid in rupees, lost value against the pound. So, in September 1900, Wodehouse started a low-level job at the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank in London. He didn't like the work and found it confusing. He later wrote a funny story about his time there. But at the time, he just wanted the workday to end so he could go home and write.

He first wrote serious articles about school sports for Public School Magazine. In November 1900, his first funny piece, "Men Who Missed Their Own Weddings," was accepted by Tit-Bits. A new boys' magazine, The Captain, also paid him well. During his two years at the bank, Wodehouse had eighty pieces published in nine different magazines.

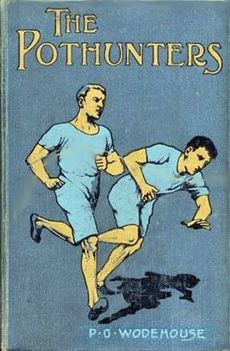

In 1901, with help from a former teacher, Wodehouse got a job writing for The Globe newspaper's popular "By the Way" column. He kept this job until 1909. Around the same time, his first novel, a school story called The Pothunters, was published in 1902. He quit the bank that month to become a full-time writer.

Between 1902 and 1909, Wodehouse wrote eight novels and co-wrote two others. He later said these were his "apprentice years" when he was just learning to write.

Wodehouse had always been fascinated by America. In 1904, he had saved enough money to visit New York. He loved it there. He wrote in his diary that the experience would be "worth many guineas in the future." This was true because few British writers had visited the US. His articles about New York life earned him more money than usual. He later said that after that trip, he was "a man who counted."

In 1904, Wodehouse also started writing for the stage. He was asked to write a song lyric for a musical comedy called Sergeant Brue. He had loved theatre since he was thirteen. His song, "Put Me in My Little Cell," was well-received. This started his career as a theatre writer, which lasted for thirty years.

In 1906, his novel Love Among the Chickens introduced his first truly original funny character: Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge. Ukridge was a clumsy character who often tried to get by without much effort. Wodehouse based him partly on a colleague. He would write more stories about Ukridge for the next sixty years.

In early 1906, the actor-manager Seymour Hicks asked Wodehouse to write songs for the Aldwych Theatre. Hicks had already hired Jerome Kern to write the music. Their first song together, "Mr. Chamberlain," was a big hit and became very popular in London.

Famous Characters Appear: 1908–1915

Wodehouse's early writing period ended in 1908 with the story The Lost Lambs. This was later published as part of the novel Mike. This book started as a school story, but Wodehouse introduced a new and very original character, Psmith. Many writers, like Evelyn Waugh and George Orwell, thought Psmith's creation was a big moment in Wodehouse's writing. Wodehouse said he based Psmith on a hotel owner named Rupert D'Oyly Carte. Psmith appeared in three more novels: Psmith in the City (1910), Psmith, Journalist (1915), and Leave It to Psmith (1923), which was set at Blandings Castle.

In May 1909, Wodehouse visited New York again. He sold two short stories for $500, which was much more than he had earned before. He quit his job at The Globe and stayed in New York for almost a year. He sold many more stories, but no American magazines offered him a steady job. Wodehouse returned to England in late 1910. He rejoined The Globe and also wrote regularly for The Strand Magazine. He visited America often between then and the start of the First World War in 1914.

Wodehouse was in New York when the war began. He couldn't join the military because of his poor eyesight. So, he stayed in the US throughout the war, focusing on his writing and theatre work. In September 1914, he married Ethel May Wayman. Their marriage was happy and lasted their whole lives. Ethel was outgoing and organized, while Wodehouse was shy and not very practical. She helped him have the peace and quiet he needed to write. They didn't have children together, but Wodehouse loved Ethel's daughter, Leonora (1905–1944), and adopted her.

Wodehouse tried different kinds of stories during these years. Psmith, Journalist, which mixed comedy with social comments, was published in 1915. In the same year, The Saturday Evening Post paid $3,500 to publish Something New. This was the first of his novels set at Blandings Castle. It was published in the US and UK in the same year. It was Wodehouse's first very funny novel and his first best-seller. Even though he wrote some gentler stories later, he became known for his funny, farcical novels. Later that year, "Extricating Young Gussie," the first story about Bertie and Jeeves, was published. These stories introduced characters that Wodehouse wrote about for the rest of his life.

The Blandings Castle stories are set in a grand English house. They show the calm Lord Emsworth trying to avoid all the distractions around him. These include young lovers, his lively brother Galahad, his bossy sisters, and anything that might bother his prize pig, the Empress of Blandings. The Bertie and Jeeves stories feature a friendly young man who is often saved from his own silly mistakes by his clever valet.

Broadway Success: 1915–1919

A third important event for Wodehouse happened in late 1915. His old songwriting partner, Jerome Kern, introduced him to the writer Guy Bolton. Bolton became Wodehouse's closest friend and a frequent collaborator. Bolton and Kern had a musical, Very Good Eddie, playing in New York. It was successful, but they thought the song lyrics could be better. So, they asked Wodehouse to join them for their next show. This was Miss Springtime (1916), which ran for 227 performances. This was a good run for that time. The team created several more hits, including Leave It to Jane (1917), Oh, Boy! (1917–18), and Oh, Lady! Lady!! (1918). Wodehouse and Bolton also wrote a few more shows with other composers. In these musicals, Wodehouse's lyrics were highly praised by critics and other lyricists.

Unlike his inspiration, W. S. Gilbert, Wodehouse preferred to have the music written first. Then, he would fit his words to the melodies. The books and lyrics for these shows made the collaborators a lot of money. They also played a big part in how American musicals developed. In the Grove Dictionary of American Music, Larry Stempel wrote that these shows brought "a new level of intimacy, cohesion, and sophistication to American musical comedy." The theatre writer Gerald Bordman called Wodehouse "the most observant, literate, and witty lyricist of his day."

The 1920s: More Popular Stories

After the war, Wodehouse's book sales kept growing. He made his existing characters even better and created new ones. Bertie and Jeeves, Lord Emsworth, and Ukridge appeared in novels and short stories. Psmith made his last appearance. Two new characters were the Oldest Member, who told golf stories, and Mr. Mulliner, who told very exaggerated tales at the Angler's Rest bar. Other young men appeared in short stories about members of the Drones Club.

The Wodehouses moved back to England and had a house in London for some years. But Wodehouse kept traveling to New York often. He continued to work in theatre. In the 1920s, he worked on nine musical comedies that were shown on Broadway or in London. These included Sally (1920) and The Cabaret Girl (1922). He also wrote non-musical plays.

Wodehouse was never a very social person, but he was more outgoing in the 1920s than at other times. He was friends with writers like A. A. Milne and Ian Hay, and stage performers.

Hollywood Adventures: 1929–1931

Films based on Wodehouse's stories had been made since 1915. But it wasn't until 1929 that Wodehouse went to Hollywood. His friend Bolton was working there as a highly paid writer for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). Ethel liked the money and social life in Hollywood. She got her husband a contract with MGM for $2,000 a week. This big salary was very helpful because the couple had lost a lot of money in the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

The actual work is negligible.... So far, I have had eight collaborators. The system is that A. gets the original idea, B. comes in to work with him on it, C. makes a scenario, D. does preliminary dialogue, and then they send for me to insert Class and what-not. Then E. and F., scenario writers, alter the plot and off we go again.

His contract started in May 1930. But the studio didn't have much for Wodehouse to do. He had free time to write a novel and nine short stories. He said, "It's odd how soon one comes to look on every minute as wasted that is given to earning one's salary." Even when the studio found a project for him, many people would change his ideas. So, his work was rarely used.

Wodehouse's contract ended after a year and was not renewed. MGM asked him to give an interview to The Los Angeles Times. Wodehouse was described as "politically naive" and "unworldly." He caused a big stir by publicly saying what he had told friends: Hollywood was inefficient, made decisions without reason, and wasted money on talented people. The interview was printed in The New York Times, and there was a lot of talk about the film industry. Many people thought the interview led to big changes in the studio system.

Some people think Wodehouse was not as naive as he seemed. Biographers suggest he was quite smart in some ways. He strongly criticized the studio owners in his short stories set in Hollywood from the early 1930s. These stories contain his sharpest and most critical humor.

Peak of Success: The 1930s

In the 1930s, Wodehouse's theatre work slowed down. He wrote or adapted four plays for London's West End. Only Leave it to Psmith (1930) had a long run. Critics said that what they missed most in the plays were Wodehouse's unique descriptions and comments from his novels. In 1934, Wodehouse worked on the book for Cole Porter's Anything Goes. But his version was almost completely rewritten by others. Wodehouse focused on writing novels and short stories. He reached the peak of his writing in this decade, writing about two books each year and earning around £100,000 annually.

Wodehouse divided his time between Britain and America. This caused problems with the tax authorities in both countries. Both the UK tax office and the US tax office wanted to tax him as a resident. After long talks, the issue was settled. But the Wodehouses decided to move to France to avoid future tax problems. They bought a house near Le Touquet.

In 1935, Wodehouse created his last regular main character, Lord Ickenham, also known as Uncle Fred. He is a character who loves to cause fun trouble in four novels and a short story. Other books from this decade include Right Ho, Jeeves, which some consider his best work, and Uncle Fred in the Springtime. The book Blandings Castle contains "Lord Emsworth and the Girl Friend," which the writer Rudyard Kipling called "one of the most perfect short stories I have ever read."

Other famous writers who admired Wodehouse included A. E. Housman and Hilaire Belloc. Belloc called Wodehouse "the best writer of our time." Wodehouse wasn't sure if his books had great literary value or just popular appeal. He must have been very happy when the University of Oxford gave him an honorary doctorate in June 1939. This visit to England for the ceremony was the last time he was in his home country.

Second World War: Being Held and Radio Talks

When the Second World War started, Wodehouse and his wife stayed at their house in Le Touquet. During the early part of the war, when there wasn't much fighting, he worked on his novel Joy in the Morning. As the Germans advanced, the nearby Royal Air Force base left. Wodehouse was offered a seat on a fighter plane, but he refused because it meant leaving Ethel and their dog behind. On May 21, 1940, with German troops coming through northern France, the Wodehouses tried to drive to Portugal to fly to the US. But their car broke down, and the roads were blocked with refugees. So, they went back home.

The Germans took over Le Touquet on May 22, 1940. Wodehouse had to report to the authorities every day. After two months, the Germans held all male enemy citizens under 60. Wodehouse was sent to a former prison in Loos on July 21. Ethel stayed in Le Touquet. The prisoners were put four to a cell, which was meant for one person. Only one bed was available per cell, given to the oldest man. Wodehouse slept on the stone floor. They were soon moved to a former army base in Liège, Belgium, run by the SS. After a week, they were moved to Huy and held in the local citadel. They stayed there until September 1940, when they were taken to Tost in what was then Germany (now Poland).

Wodehouse's family and friends didn't know where he was after France fell. But an article by an Associated Press reporter who visited Tost in December 1940 led to calls for his release. Influential people in the US, including Senator W. Warren Barbour, asked the German ambassador to release him. The Germans refused, but Wodehouse was given a typewriter. To pass the time, he wrote Money in the Bank. While in Tost, he secretly sent postcards to his US literary agent. He asked for $5 to be sent to various people in Canada, mentioning his name. These were the families of Canadian prisoners of war. Wodehouse's messages were the first news that their sons were alive. Wodehouse risked severe punishment for this, but he managed to get around the German censor.

On June 21, 1941, while playing cricket, Wodehouse was visited by two members of the Gestapo (German secret police). He was given ten minutes to pack and then taken to the Hotel Adlon, a luxury hotel in Berlin. He stayed there at his own expense, using money from his German book royalties. He was released from being held a few months before his sixtieth birthday, which was the age when civilian prisoners were released by the Nazis. Soon after, Wodehouse was persuaded to make five radio broadcasts to the US through German radio. The broadcasts, called How to be an Internee Without Previous Training, were funny stories about his time as a prisoner. They even gently made fun of his captors. The German propaganda ministry arranged for these recordings to be broadcast to Britain in August. The day after Wodehouse recorded his last program, Ethel joined him in Berlin. She had sold most of her jewelry to pay for the trip.

After the War: Reactions and Investigations

The reaction in Britain to Wodehouse's broadcasts was very negative. He was called names like "traitor" and "coward," even though many people who criticized him hadn't heard the programs. A newspaper article said that Wodehouse "lived luxuriously because Britain laughed with him, but when the laughter was out of his country's heart, ... [he] was not ready to share her suffering." Several libraries removed Wodehouse's novels from their shelves.

On July 15, the journalist William Connor, using the name Cassandra, gave a radio speech criticizing Wodehouse. This speech caused a lot of complaints from listeners across the country. Wodehouse's biographer, Joseph Connolly, called the broadcast "inaccurate, spiteful and slanderous." This broadcast was ordered by Duff Cooper, the Minister of Information, even though the BBC strongly protested. Many letters appeared in British newspapers, both supporting and criticizing Wodehouse. His friend, A. A. Milne, wrote a letter criticizing him. Other authors like Compton Mackenzie defended Wodehouse. Most people defending Wodehouse agreed that he had acted foolishly. Some people wrote to say that all the facts weren't known yet, so a fair judgment couldn't be made. The BBC thought Wodehouse's actions were just "ill advised."

When Wodehouse heard about the controversy, he contacted the British Foreign Office through the Swiss embassy in Berlin. He tried to explain his actions and return home, but the German authorities wouldn't let him leave. In a 1953 book of letters, Wodehouse wrote, "Of course I ought to have had the sense to see that it was a loony thing to do to use the German radio for even the most harmless stuff, but I didn't. I suppose prison life saps the intellect." The reaction in America was mixed. Some accused Wodehouse of helping the Nazis, but the Department of War used the interviews as an example of anti-Nazi propaganda.

The Wodehouses stayed in Germany until September 1943. Because of Allied bombings, they were allowed to move back to Paris. They were living there when the city was freed on August 25, 1944. Wodehouse reported to the American authorities the next day. He was later visited by Malcolm Muggeridge, an intelligence officer. Muggeridge quickly liked Wodehouse and thought the idea of him being a traitor was "ludicrous." He described Wodehouse as "ill-fitted to live in an age of ideological conflict." On September 9, Wodehouse was investigated by a British intelligence officer. The officer's report said Wodehouse's behavior was "unwise" but advised against further action. On November 23, the Director of Public Prosecutions decided there was no reason to charge Wodehouse.

In November 1944, Duff Cooper became the British ambassador to France. He was given a place to stay at the Hôtel Le Bristol, where the Wodehouses were living. Cooper complained, and the couple were moved to a different hotel. The Wodehouses were then arrested by French police and held, even though no charges were made. Muggeridge found them and got Ethel released right away. Four days later, he made sure Wodehouse was declared unwell and moved to a nearby hospital, which was more comfortable. While in the hospital, Wodehouse worked on his novel Uncle Dynamite.

While still held by the French, Wodehouse was again mentioned in the British Parliament in December 1944. Members of Parliament wondered if the French could send him back to Britain for trial. The Foreign Secretary said there were "no grounds upon which we could take action." Two months later, George Orwell wrote an essay called "In Defence of P.G. Wodehouse." He said that Wodehouse's actions in 1941 showed nothing worse than "stupidity." Orwell believed Wodehouse's "moral outlook has remained that of a public-school boy," and he had a "complete lack... of political awareness."

On January 15, 1945, the French authorities released Wodehouse. But they didn't tell him until June 1946 that he wouldn't face any official charges and was free to leave the country.

Living in America: 1946–1975

After getting American visas in July 1946, the Wodehouses got ready to return to New York. They were delayed because Ethel wanted new clothes and Wodehouse wanted to finish his novel, The Mating Season, in the quiet French countryside. In April 1947, they sailed to New York. Wodehouse was relieved by the friendly welcome he received from the many reporters waiting for him. Ethel found a nice apartment in Manhattan, but Wodehouse wasn't comfortable. New York had changed a lot since before the war. The magazines that used to pay him well were not doing as well, and they weren't very interested in him. He was asked about writing for Broadway, but he didn't feel at home in the post-war theatre. He had money problems, with large amounts of money temporarily stuck in Britain. For the first time in his career, he had no ideas for a new novel. He didn't finish one until 1951.

Wodehouse remained unsettled until he and Ethel left New York City for Long Island. Their friends, the Boltons, lived in Remsenburg, part of the Southampton area. Wodehouse often stayed with them, and in 1952, he and Ethel bought a house nearby. They lived in Remsenburg for the rest of their lives. Between 1952 and 1975, he published over twenty novels, two short story collections, a book of his letters, a memoir, and some of his magazine articles. He still hoped to revive his theatre career. In 1959, an off-Broadway revival of the 1917 musical Leave It to Jane was a surprise hit. But his few post-war stage works didn't make much of an impact.

Ethel visited England in 1948, but Wodehouse never left America after 1947. It wasn't until 1965 that the British government privately said he could return without legal trouble. But by then, he felt too old to travel. Some biographers believe this exile helped Wodehouse's writing. It allowed him to keep writing about an ideal England he imagined, rather than the real England after the war. During their years on Long Island, the couple often took in stray animals and gave a lot of money to a local animal shelter.

In 1955, Wodehouse became an American citizen, but he also remained a British subject. This meant he could still receive British honors. He was considered for a knighthood three times starting in 1967, but the honor was blocked twice by British officials. In 1974, the British prime minister, Harold Wilson, helped Wodehouse get a knighthood (KBE). This was announced in January 1975. The Times newspaper said that Wodehouse's honor showed "official forgiveness for his wartime indiscretion."

The next month, Wodehouse went to Southampton Hospital, Long Island, for a skin problem. While there, he had a heart attack and died on February 14, 1975, at the age of 93. He was buried at Remsenburg Presbyterian Church four days later. Ethel lived for more than nine years after him. His adopted daughter, Leonora, had died suddenly in 1944.

Images for kids

-

The English Heritage blue plaque for Wodehouse at 17 Dunraven Street, Mayfair, in the City of Westminster

See also

In Spanish: P. G. Wodehouse para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |