Evelyn Waugh facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Evelyn Waugh

|

|

|---|---|

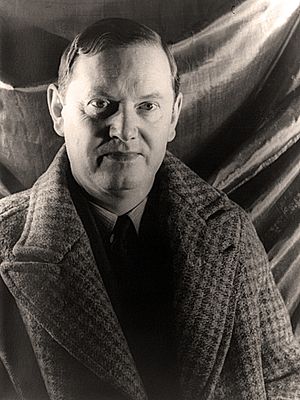

Evelyn Waugh, circa 1940

|

|

| Born | Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh 28 October 1903 West Hampstead, London, England |

| Died | 10 April 1966 (aged 62) Combe Florey, Somerset, England |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Education | Lancing College |

| Alma mater | Hertford College, Oxford |

| Period | 1923–1964 |

| Genre | Novel, biography, short story, travelogue, autobiography, satire, humour |

| Spouses |

Evelyn Gardner

(m. 1928; annulled 1936)Laura Herbert

(m. 1937) |

| Children | 7, including Auberon Waugh |

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (born October 28, 1903 – died April 10, 1966) was a famous English writer. He wrote many novels, biographies, and travel books. He was also a journalist and reviewed books. Some of his most well-known works include the funny stories Decline and Fall (1928) and A Handful of Dust (1934). He also wrote the novel Brideshead Revisited (1945) and the Second World War series Sword of Honour (1952–1961). Many people think he was one of the best English writers of the 20th century.

Waugh's father was a publisher. Evelyn went to Lancing College and then Hertford College, Oxford. He worked as a school teacher for a short time before becoming a full-time writer. When he was young, he made friends with many rich and important people. He enjoyed spending time in fancy country houses. In the 1930s, he traveled a lot, often as a special reporter for newspapers. He reported from Abyssinia during the 1935 Italian invasion.

During the Second World War, he served in the British armed forces. He was first in the Royal Marines and then in the Royal Horse Guards. Waugh was a sharp observer and used his experiences and the people he met in his stories. He often made these experiences humorous. He even wrote about his own mental health struggles in a fictional way.

In 1930, after his first marriage ended, Waugh became a Catholic. He strongly believed in traditional ways and did not like changes to the Church. The changes made by the Second Vatican Council (1962–65) upset him greatly, especially the new way of saying Mass. This, along with his dislike for the new welfare system after the war and his declining health, made his final years difficult. However, he continued to write. He often seemed distant to others, but he was very kind to his friends. After he died in 1966, more people discovered his books through TV shows and movies, like the 1981 TV series Brideshead Revisited.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Evelyn Waugh was born on October 28, 1903. His parents were Arthur Waugh (1866–1943) and Catherine Charlotte Raban (1870–1954). His family had roots in England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, and France. His father, Arthur Waugh, worked in publishing and was a literary critic. In 1902, he became the managing director of Chapman and Hall, a company that published books by Charles Dickens.

Evelyn's older brother, Alec Waugh, was born in 1898 and also became a well-known novelist. Evelyn was born in West Hampstead, London. He was christened Arthur Evelyn St John Waugh but was always known as Evelyn.

Childhood Years

Moving to Golders Green

In 1907, the Waugh family moved to Underhill, a house his father built near Golders Green. This area was then mostly countryside. Evelyn had his first lessons at home from his mother. He was very close to her. His father was closer to his older brother, Alec, which sometimes made Evelyn feel left out.

In September 1910, Evelyn started at Heath Mount preparatory school. He was a lively boy with many interests. He had already written his first story, "The Curse of the Horse Race." A teacher named Aubrey Ensor helped him with his writing. Evelyn was happy at Heath Mount for six years. He said he was "quite a clever little boy" and rarely found lessons hard. He was physically strong and sometimes bullied weaker boys, including the future photographer Cecil Beaton.

Outside school, Evelyn and other children put on plays, often written by him. During the First World War, which started in 1914, Evelyn and other boys from his Boy Scout troop sometimes worked as messengers at the War Office. Evelyn hoped to see Lord Kitchener but never did.

Family holidays were often spent with his aunts in Midsomer Norton, Somerset. Evelyn loved these times. There, he became very interested in the rituals of the Anglican Church. This was the start of his spiritual journey. He even served as an altar boy. In his last year at Heath Mount, Waugh started and edited the school magazine, The Cynic.

Life at Lancing College

Evelyn was expected to go to Sherborne School, like his father and brother Alec. However, in 1915, Alec had to leave Sherborne because of a problem with school rules. Alec then wrote a novel called The Loom of Youth (1917) about school life. This book caused a stir and made it impossible for Evelyn to go to Sherborne. So, in May 1917, Evelyn was sent to Lancing College, which he thought was not as good.

Despite his first feelings, Waugh soon liked Lancing. He became known for his artistic taste. In November 1917, his essay "In Defence of Cubism" was published in an arts magazine. This was his first published article. After the war, some younger teachers returned to the school. They encouraged Waugh to write and believed he had a great future. Another teacher, Francis Crease, taught him calligraphy and design. Some of Evelyn's designs were even used on book covers.

In his last years at Lancing, Waugh did very well. He was a house captain, editor of the school magazine, and president of the debating society. He won many art and literature prizes. He also lost most of his religious beliefs during this time. He started writing a novel about school life but stopped after about 5,000 words. He finished school by winning a scholarship to study History at Hertford College, Oxford, and left Lancing in December 1921.

Oxford University Life

Waugh started at Oxford in January 1922. He quickly wrote to friends about how much he enjoyed his new life. He said he did "no work here and never go to Chapel." At first, he followed the usual student activities. He smoked a pipe, bought a bicycle, and gave his first speech at the Oxford Union. He also wrote reviews for Oxford magazines and was a film critic. He became secretary of his college's debating society. He did enough work to pass his first history exam.

In October 1922, his Oxford life changed when sophisticated students like Harold Acton and Brian Howard arrived. They became the center of a group called the Hypocrites' Club, which Waugh joined. He wrote reviews and short stories for university journals and became known as a talented artist. However, he stopped focusing on his studies. This led to arguments with his history tutor, C. R. M. F. Cruttwell. Waugh later admitted he was "fatuously haughty" in his replies. Their dislike for each other continued for years. Waugh even used Cruttwell's name for silly or unpleasant characters in his early novels.

Waugh's carefree lifestyle continued into his last year at Oxford in 1924. He hinted at emotional difficulties in a letter to a friend. He did just enough work to pass his final exams with a low grade. Because he had not completed enough terms, he lost his scholarship and could not return for his final term. So, he left Oxford without a degree.

Back home, Waugh started a novel called The Temple at Thatch. He also worked with friends on a film, The Scarlet Woman. He spent much of the summer with a friend, Alastair Graham. After Graham left, Waugh enrolled in an art school in London, Heatherley's.

Starting His Career

Teaching and Early Writing

Waugh started at Heatherley's in September 1924 but quickly got bored and left. He spent weeks going to parties in London and Oxford. Needing money, he found a teaching job at Arnold House, a boys' school in North Wales, starting in January 1925. He took his novel notes with him, hoping to write in his free time. The school was gloomy, and a short trip to London and Oxford made him feel even more isolated.

In summer 1925, Waugh's hopes rose when he thought he got a job in Pisa, Italy. He would be a secretary to the writer C. K. Scott Moncrieff. Believing the job was his, Waugh quit Arnold House. He had sent his novel chapters to a friend, Harold Acton, for feedback. Acton's reply was so negative that Waugh immediately burned his manuscript. Soon after, he learned the job in Italy had fallen through.

For the next two years, Waugh taught at schools in Aston Clinton and Notting Hill. He thought about other jobs like printing or making furniture. He took evening classes in carpentry while still writing. A short story, "The Balance," was his first published fiction in 1926. He also wrote an essay on the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, which was printed privately. This led to a contract to write a biography of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which he finished in 1927. He also started writing a funny novel, which became Decline and Fall. He stopped teaching and briefly worked as a reporter for the Daily Express, but it wasn't successful. In 1927, he met and fell in love with Evelyn Gardner.

Marriage and Success

In December 1927, Waugh and Evelyn Gardner got engaged. Her mother did not approve, thinking Waugh lacked good character. Among their friends, they were called "He-Evelyn" and "She-Evelyn." At this time, Waugh relied on money from his father and small earnings from writing. His Rossetti biography was published in April 1928 and was generally well-received.

When Decline and Fall was finished, Chapman & Hall agreed to publish it. This allowed Waugh and Gardner to get married sooner. They wed on June 27, 1928, with only a few friends present. They lived in a small flat in Canonbury Square, Islington. The first months of their marriage were hard due to lack of money and Gardner's poor health.

In September 1928, Decline and Fall was published and received great praise. By December, it was in its third printing, and the American rights were sold. Because of his success, Waugh was asked to write travel articles in exchange for a free trip. He and Gardner started a cruise in February 1929 as a delayed honeymoon. The trip was cut short when Gardner got pneumonia. They returned home in June. A month later, Gardner told him she was in love with their friend, John Heygate. After trying to fix things, a shocked Waugh filed for divorce on September 3, 1929. They reportedly met only once more, during the process to annul their marriage years later.

Becoming a Novelist and Journalist

Finding His Voice

After his divorce, friends noticed a new "hardness and bitterness" in Waugh. Despite feeling very sad, he quickly returned to his work and social life. He finished his second novel, Vile Bodies, and wrote articles. During this time, Waugh often stayed at friends' houses, as he had no settled home for eight years.

Vile Bodies, a funny story about the "Bright Young People" of the 1920s, was published on January 19, 1930. It was Waugh's first big commercial success. As a best-selling author, he could now earn more money for his journalism. He wrote Labels, a detached account of his honeymoon cruise.

Becoming Catholic

On September 29, 1930, Waugh became a Catholic. This surprised his family and some friends, but he had thought about it for a while. He had lost his Anglican faith at Lancing and lived without much religion at Oxford. However, his diaries from the mid-1920s show he had religious discussions and went to church regularly. His friend Olivia Plunket-Greene, who had converted in 1925, influenced him. She led him to Father Martin D'Arcy, a Jesuit priest. Father D'Arcy convinced Waugh that "the Christian revelation was genuine." In 1949, Waugh explained that he converted because he realized life was "unintelligible and unendurable without God."

Travels and New Books

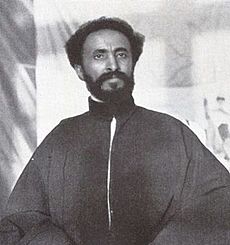

On October 10, 1930, Waugh went to Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) to cover the coronation of Haile Selassie for several newspapers. He reported that the event was a big show to make Abyssinia look civilized, hiding how the emperor really gained power. A trip through British East Africa and the Belgian Congo led to two books: the travel book Remote People (1931) and the funny novel Black Mischief (1932).

Waugh's next long trip, in winter 1932–1933, was to British Guiana in South America. He traveled by steam launch into the jungle. His adventures became part of two more books: his travel account Ninety-two Days and the novel A Handful of Dust, both published in 1934.

After returning from South America, Waugh faced criticism from a Catholic journal about parts of Black Mischief. He defended himself in a letter to the Archbishop of Westminster. In summer 1934, he went on an expedition to Spitsbergen in the Arctic, which he did not enjoy. He then decided to write a major Catholic biography. He chose the Jesuit martyr Edmund Campion as his subject. The book, published in 1935, was controversial because it was strongly pro-Catholic. However, it won him the Hawthornden Prize.

He returned to Abyssinia in August 1935 to report on the start of the Second Italo-Abyssinian War for the Daily Mail. Waugh believed Abyssinia was "a savage place which Mussolini was doing well to tame." He saw little fighting and was not very serious as a war correspondent. Another reporter, William Deedes, noted Waugh's snobbery but also his courage during air attacks. Waugh wrote about his Abyssinian experiences in Waugh in Abyssinia (1936). A more famous account is his novel Scoop (1938), where the main character, William Boot, is loosely based on Deedes.

Waugh's circle of friends grew to include many famous people. He often stayed at Madresfield Court, a country house that became like a home to him. In 1933, he met Laura Herbert, the 17-year-old sister of a friend.

Second Marriage and Family

After becoming Catholic, Waugh believed he could not remarry while his first wife, Evelyn Gardner, was alive. However, he wanted a wife and children. In October 1933, he started the process to annul his first marriage. The annulment was granted on July 4, 1936. By then, Waugh had fallen in love with Laura Herbert. He proposed to her in spring 1936. Laura's family was aristocratic and Catholic, and some were hesitant because Laura was also a cousin of Evelyn Gardner. Despite some family opposition, they married on April 17, 1937, in London.

As a wedding gift, Laura's grandmother bought them Piers Court, a country house in Gloucestershire. They had seven children, though one died as a baby. Their first child, Maria Teresa, was born in 1938, and a son, Auberon Alexander, in 1939. Between these births, Scoop was published in May 1938 and was very popular. In August 1938, Waugh and Laura took a three-month trip to Mexico. He wrote Robbery Under Law based on his experiences there. In this book, he clearly stated his conservative beliefs.

Second World War Experiences

Royal Marine and Commando

Waugh left Piers Court on September 1, 1939, when the Second World War began. He moved his family to Pixton Park in Somerset while he looked for military work. He also started writing a new novel, but stopped when he joined the Royal Marines in December. He trained at Chatham naval base. He never finished that novel, but parts were published later.

Waugh's training made him very stiff. In April 1940, he was promoted to captain and given command of a company of marines. However, he was not a popular officer, being proud and short-tempered with his men. His battalion did not see action during the German invasion of Europe. Waugh found it hard to fit into military life and soon lost his command. He became the battalion's Intelligence Officer. In this role, he finally saw action in Operation Menace in West Africa in August 1940. This mission failed, and Waugh commented, "Bloodshed has been avoided at the cost of honour."

In November 1940, Waugh joined a commando unit called "Layforce." In February 1941, they sailed to the Mediterranean and tried to recapture Bardia in Libya, but failed. In May, Layforce helped evacuate Crete. Waugh was shocked by the chaos and lack of discipline among the retreating troops. In July, on his way home, he wrote Put Out More Flags (1942), a novel about the early war months. Back in Britain, he transferred to the Royal Horse Guards in May 1942. On June 10, 1942, Laura gave birth to Margaret, their fourth child.

Writing Brideshead and Yugoslavia

Waugh was happy about his transfer but soon felt disappointed because he couldn't find opportunities for active service. His father died on June 26, 1943, and family matters kept him from going to North Africa with his brigade. Despite his bravery, his unmilitary and disobedient nature made him difficult to employ as a soldier. After periods of inactivity, Waugh started parachute training but broke his leg during an exercise. While recovering, he asked for three months' unpaid leave to write a novel. His request was granted, and he went to Chagford, Devon, in January 1944 to work alone. The result was Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder (1945). This was his first clearly Catholic novel.

Waugh extended his leave until June 1944. Soon after returning to duty, he was asked by Randolph Churchill to join a mission to Yugoslavia. In early July, he flew with Churchill to the Croatian island of Vis. There, they met Marshal Tito, the Communist leader fighting the Axis forces with Allied support. Waugh and Churchill were injured in a plane crash, delaying their mission.

The mission eventually arrived at Topusko. Their duties between the British Army and the Communist Partisans were light. Waugh did not like the Communist-led Partisans and disliked Tito. He became very interested in the welfare of the Catholic Church in Croatia. He believed it had suffered and would suffer more under Communist control. He wrote a long report, "Church and State in Liberated Croatia." After visiting Dubrovnik and Rome, Waugh returned to London in March 1945 to present his report. However, the Foreign Office suppressed it to maintain good relations with Tito.

Post-War Life

Fame and New Works

Brideshead Revisited was published in London in May 1945. Waugh was sure it was a good book, calling it "my first novel rather than my last." It was a huge success, bringing him fame, money, and literary recognition. Despite this, Waugh's main concern after the war was the fate of Eastern European Catholics. He felt they were betrayed to Stalin's Soviet Union by the Allies. He saw little moral difference between the warring sides. He was briefly happy when Winston Churchill and his party lost the 1945 election. However, he saw the Labour Party coming to power as the start of a new "Dark Age."

In September 1945, after leaving the army, he returned to Piers Court with his family. Another daughter, Harriet, had been born in 1944. For the next seven years, he spent much time in London or traveling. In March 1946, he visited the Nuremberg Trials. Later that year, he was in Spain. Waugh wrote about his frustrating experiences of postwar European travel in a short novel, Scott-King's Modern Europe. In February 1947, he made the first of several trips to the United States to discuss filming Brideshead. The film project failed, but Waugh used his time in Hollywood to visit a cemetery. This visit inspired his funny story about American views on death, The Loved One (1948). In 1951, he visited the Holy Land. In 1953, he traveled to Goa to see the remains of the 16th-century Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier.

Between his travels, Waugh worked on Helena, a novel about the discoverer of the True Cross. He believed it was "far the best book I have ever written." It wasn't a big public success, but his daughter Harriet said it was "the only one of his books that he ever cared to read aloud."

In 1952, Waugh published Men at Arms, the first book in his war trilogy. It was based on his own experiences from the early war. Other books from this time included When The Going Was Good (1946), a collection of his pre-war travel writing, and Love Among the Ruins (1953). This was a story about a future world where Waugh showed his dislike for modern society. Nearing 50, Waugh looked older than his age. He was "selectively deaf, rheumatic, irascible." Two more children, James (born 1946) and Septimus (born 1950), completed his family.

From 1945 onwards, Waugh became a keen collector of Victorian paintings and furniture. He filled Piers Court with his finds, often from London's Portobello Market. Some of his purchases were very smart. He also started writing knowledgeable reviews and articles about painting from 1949.

Health Challenges

By 1953, Waugh's popularity as a writer was decreasing. He was seen as out of touch with the times, and the high fees he asked for were harder to get. He was running out of money, and progress on the second book of his war trilogy, Officers and Gentlemen, had stopped. His health was getting worse. A lack of money led him to agree to a BBC radio interview in November 1953. He felt the interviewers tried to make him look foolish.

In early 1954, Waugh's doctors suggested a change of scenery due to his declining health. On January 29, he took a ship to Ceylon. Within days, he complained of "other passengers whispering about me" and hearing voices. He left the ship in Egypt and flew to Colombo, but the voices followed him. Alarmed, Laura sought help. Waugh eventually made his own way back, believing he was possessed by devils. A medical exam showed he had bromide poisoning from his medication. When his medicine was changed, the voices and hallucinations quickly disappeared. Waugh was delighted, telling friends he had been "mad." He later wrote about this experience in The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold (1957).

In 1956, a short film was made about Waugh. In it, he said he hated the modern world and wished he had been born centuries earlier. He disliked modern transport and communication, refused to drive or use the telephone, and wrote with an old-fashioned pen.

Later Works and Final Years

Once healthy again, Waugh finished Officers and Gentlemen. In June 1955, a journalist and her friend arrived uninvited at Piers Court and demanded an interview. Waugh sent them away and wrote a funny account for The Spectator. However, he was bothered by the incident and decided to sell Piers Court, feeling it was "polluted." In late 1956, the family moved to Combe Florey House in Somerset. In January 1957, Waugh won money in a lawsuit against the newspaper and journalist for an article that suggested his book sales were very low.

Gilbert Pinfold was published in summer 1957. Waugh called it "my barmy book." His next major book was a biography of his friend Ronald Knox, a Catholic writer who had died. This took two years to write, delaying the third volume of his war trilogy. In June 1958, his son Auberon was badly hurt in a shooting accident while serving in the army. Waugh remained distant and did not immediately visit Auberon.

Although most of Waugh's books sold well, and he earned good money from journalism, his spending habits meant he often had money problems and tax bills. In 1950, to avoid taxes, he set up a trust fund for his children. By 1960, money issues led him to agree to a BBC Television interview. He answered questions calmly, appearing "world-weary bored."

In 1960, Waugh was offered a CBE honor but turned it down. He felt he should have been given a higher honor, a knighthood. In September, he wrote his last travel book, A Tourist in Africa. He enjoyed the trip but "despised" the book itself. He then worked on the last part of his war trilogy, published in 1961 as Unconditional Surrender.

Decline and Death

As he neared his sixties, Waugh's health was poor. He looked older than his age, described as "fat, deaf, short of breath." In 1962, Waugh began writing his autobiography and his final fiction, the short story Basil Seal Rides Again. This story, featuring a character from his earlier novels, was published in 1963. That same year, he received the title Companion of Literature from the Royal Society of Literature, its highest honor. When the first part of his autobiography, A Little Learning, was published in 1964, Waugh's careful writing meant friends were not embarrassed.

Waugh had welcomed Pope John XXIII in 1958. However, he became very worried by the decisions from the Second Vatican Council, which started in 1962. Waugh strongly opposed changes to the Church. He was especially upset by replacing the universal Latin Mass with local languages. He wrote an article in The Spectator arguing against the changes. He told Nancy Mitford that "the buggering up of the Church is a deep sorrow to me."

In 1965, a new money problem arose from a flaw in his children's trust fund, and a large amount of back tax was demanded. His agent negotiated a settlement. To raise funds, Waugh signed contracts to write several books, but his declining health prevented him from working on them, and the contracts were canceled. His only major literary work in 1965 was editing his three war novels into one volume, Sword of Honour.

On Easter Day, April 10, 1966, after attending a Latin Mass, Waugh died of heart failure at his home in Combe Florey, at age 62. He was buried in a special consecrated plot outside the Anglican churchyard. A Latin Mass was held for him in Westminster Cathedral on April 21, 1966.

Character and Beliefs

During his life, Waugh made enemies and offended many people. One writer said he was "the nastiest-tempered man in England." His son, Auberon, said that his father's strong personality made important people "quail in front of him."

However, some biographers say that the idea of Evelyn Waugh as a "snobbish misanthrope" is not entirely true. They ask why such an unpleasant man would be loved by so many friends. He was generous to individuals and Catholic causes. After winning a lawsuit, he even sent his opponent a bottle of champagne. Some say his outward rudeness was not always serious but a way to find someone witty enough to argue with. Waugh also made fun of himself, often acting like a grumpy old man, which was a comic act.

As a natural conservative, Waugh believed that class differences and unequal wealth were normal. He thought "no form of government [was] ordained by God as being better than any other." After the war, he criticized socialism and complained that the Conservative Party never "put the clock back a single second." Waugh never voted in elections.

Waugh's Catholic faith was very important to him. He believed the Church was the last defense against a new "Dark Age" brought on by the welfare state and working-class culture. He was very strict in his faith. He admitted that his hardest task was to balance his faith with his indifference to other people. When asked how he could be a Christian with his often rude behavior, Waugh replied that "were he not a Christian he would be even more horrible."

Waugh's conservative views also applied to art. While he praised some younger writers, he disliked other literary groups. He thought the literary world was "sinking into black disaster." As a schoolboy, he liked Cubism, but he soon lost interest in modern art. In 1945, Waugh said that Pablo Picasso's art was a "mesmeric trick." He admired George Orwell despite their political differences, because of their shared patriotism and sense of right and wrong. Orwell, in turn, said Waugh was "about as good a novelist as one can be... while holding untenable opinions."

Waugh has been criticized for expressing racist and anti-Semitic views. Some describe his anti-Semitism as his "most persistently noticeable nastiness." His belief in white superiority was seen as an extension of his views on social hierarchy.

His Works and Style

Themes and Writing Style

Waugh's novels often use events from his own life, but he said that it's wrong to assume a novelist only writes about what they see. Readers should not think the author agrees with the opinions of his characters. However, a critic noted that Waugh's detailed descriptions of social prejudices and the language used to express them were part of his careful observation of his time.

Critic Clive James said Waugh wrote "a more unaffectedly elegant English" than almost anyone. As his talent grew, he kept "an exquisite sense of the ludicrous, and a fine aptitude for exposing false attitudes." In his early career, before becoming Catholic in 1930, Waugh wrote about the "Bright Young People." His first two novels, Decline and Fall (1928) and Vile Bodies (1930), humorously show a pointless society with unbelievable characters. A common feature in his early novels is quick, unnamed dialogue where you can easily tell who is speaking. At the same time, Waugh wrote serious essays, criticizing his own generation as "crazy and sterile."

Waugh's conversion to Catholicism did not immediately change his next two novels, Black Mischief (1934) and A Handful of Dust (1934). But in A Handful of Dust, the funny parts are less strong, and the main character, Tony Last, feels more like a real person. Waugh's first story with a Catholic theme was "Out of Depth" (1933). From the mid-1930s, Catholicism and conservative politics appeared more in his non-fiction. Then he returned to his earlier style with Scoop (1938), a novel about journalism.

In Work Suspended and Other Stories, Waugh introduced more "real" characters and a first-person narrator. This hinted at the style he would use in Brideshead Revisited. Brideshead explores the meaning of life without God and is the first novel where Waugh clearly shows his conservative religious and political views. In a 1946 article, Waugh said that future novels would try to show "man in his relation to God." His novel Helena (1950) is his most philosophical Christian book.

In Brideshead, the working-class officer Hooper shows a theme in Waugh's later novels: the rise of average people in the "Age of the Common Man." In the trilogy Sword of Honour (1952–1961), this idea is shown through the character "Trimmer," a lazy fraud who succeeds by trickery. In the short novel "Scott-King's Modern Europe" (1947), Waugh's sadness about the future is clear. Similarly, the novel Love Among the Ruins (1953) is set in a future Britain where society is so unpleasant that euthanasia is the most desired government service. Of his postwar novels, The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold (1957) is seen as a "mock-novel," a playful invitation to a game. Waugh's last fiction, "Basil Seal Rides Again" (1962), features characters from his pre-war novels. Waugh admitted it was an "old attempt to recapture the manner of my youth."

Lasting Reputation

In 1973, Waugh's diaries were published, revealing details about his private life and thoughts. This caused controversy. Although Waugh had removed embarrassing parts about his Oxford years and first marriage, enough remained to create a negative image of him as intolerant and snobbish. Some of his supporters argued this image came from poor editing of the diaries. However, a popular idea of Waugh as a "monster" developed. When his letters were published in 1980, his reputation was debated further.

The publication of his diaries and letters led to more interest in Waugh's works and new books about him. Several biographies and critical studies have been produced. A collection of his journalism and reviews was published in 1983, showing more of his ideas. The 1981 Granada Television TV show Brideshead Revisited introduced a new generation to Waugh's books in Britain and America. Its nostalgic look at a past English way of life appealed to American audiences. Time magazine called the series "a novel... made into a poem" and listed it among the "100 Best TV Shows of All Time." There have been other movie adaptations of Waugh's books: A Handful of Dust in 1988, Vile Bodies (filmed as Bright Young Things) in 2003, and Brideshead Revisited again in 2008. These popular adaptations have kept the public's interest in Waugh's novels, which are still in print and continue to sell well. Many of his books have been listed among the world's greatest novels.

One biographer concluded that beneath his public image, Waugh was "a dedicated artist and a man of earnest faith." Graham Greene called him "the greatest novelist of my generation." Time magazine called him "the grand old mandarin of modern British prose." Nancy Mitford said of him, "What nobody remembers about Evelyn is that everything with him was jokes. Everything."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Evelyn Waugh para niños

In Spanish: Evelyn Waugh para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |