Arthur Sullivan facts for kids

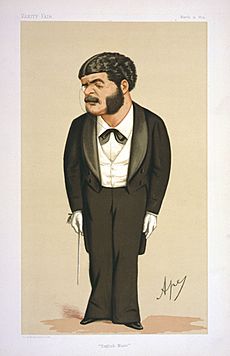

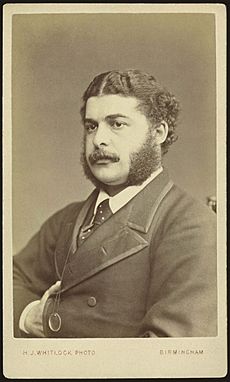

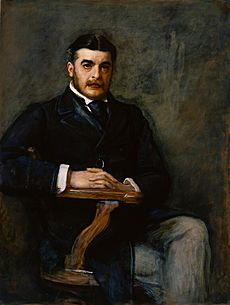

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (born May 13, 1842 – died November 22, 1900) was a famous English composer. He is best known for his 14 comic operas created with the writer W. S. Gilbert. These include very popular shows like H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, and The Mikado. Sullivan wrote many different kinds of music. He composed 24 operas, many orchestral pieces, choral works, two ballets, and music for plays. He also wrote church music, songs, and piano pieces. Some of his most famous songs are "Onward, Christian Soldiers" and "The Lost Chord".

Arthur Sullivan's father was a military bandmaster. Arthur composed his first song at just eight years old. Later, he sang as a soloist in the boys' choir of the Chapel Royal. In 1856, when he was 14, he won the first Mendelssohn Scholarship. This allowed him to study music at the Royal Academy of Music in London. Then he went to the Leipzig Conservatoire in Germany. His final project there was music for Shakespeare's play The Tempest (1861). This music was a big success when it was first performed in London. Some of his early important works included a ballet, L'Île Enchantée (1864), a symphony, and a cello concerto (both 1866). To earn more money, he also wrote hymns and popular songs. He worked as a church organist and music teacher for a while.

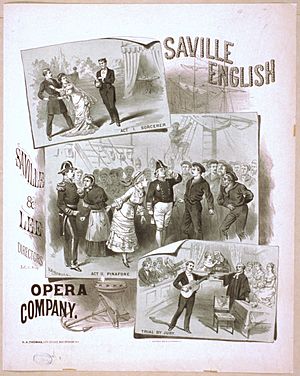

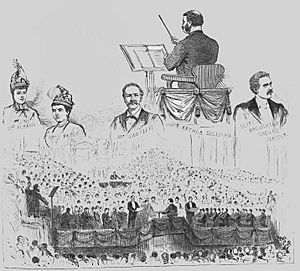

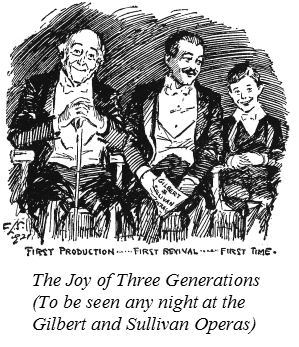

In 1866, Sullivan wrote a short comic opera called Cox and Box. People still perform this opera today. His first opera with W. S. Gilbert was Thespis in 1871. Four years later, a theatre manager named Richard D'Oyly Carte asked Gilbert and Sullivan to create a short show. This was Trial by Jury (1875). It was a huge success! Because of this, they wrote twelve more full-length comic operas together. After the amazing success of H.M.S. Pinafore (1878) and The Pirates of Penzance (1879), Carte used his profits to build the Savoy Theatre in 1881. Their joint works became known as the Savoy operas. The Mikado (1885) and The Gondoliers (1889) are among their most famous later operas. Gilbert and Sullivan had a disagreement in 1890, but they worked together again in the 1890s for two more operas. However, these new operas were not as popular as their earlier ones.

During the 1880s, Sullivan also wrote some serious pieces. These included two cantatas: The Martyr of Antioch (1880) and The Golden Legend (1886). The Golden Legend became his most popular choral work. He also wrote music for several Shakespeare plays in London's West End. Sullivan's only grand opera was Ivanhoe. It was successful at first in 1891, but it is rarely performed now. In his last ten years, Sullivan kept composing comic operas with other writers. He also wrote other important and smaller musical works. He died at 58, known as Britain's top composer. His style of comic opera influenced many musical theatre composers who came after him. His music is still performed, recorded, and copied today.

Contents

Life and Career Highlights

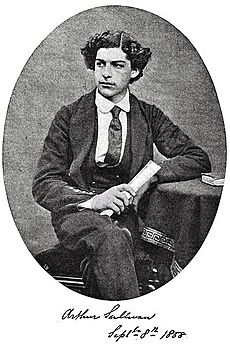

Early Life and Musical Talent

Arthur Sullivan was born on May 13, 1842, in Lambeth, London. He was the younger of two sons. His father, Thomas Sullivan, was a military bandmaster and music teacher. His mother, Mary Clementina, was English with Irish and Italian family. From 1845 to 1857, Thomas Sullivan worked at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. He was the bandmaster there and also taught music privately. Young Arthur learned to play many instruments in the band. He even composed a song, "By the Waters of Babylon," when he was only eight years old.

Arthur's father saw his son's great talent. However, he knew that a music career could be uncertain. So, he tried to discourage Arthur from becoming a musician. Arthur went to a private school in Bayswater. In 1854, he convinced his parents and headmaster to let him try out for the choir of the Chapel Royal. Even though he was almost 12, which was a bit old for a boy singer, he was accepted. He quickly became a soloist. By 1856, he was the "first boy" in the choir. Even at this young age, Arthur's health was delicate, and he tired easily.

Arthur learned a lot from Reverend Thomas Helmore, who was the Master of the Children of the Chapel Royal. Arthur started writing songs and anthems. Helmore encouraged his composing. He even helped get one of Arthur's pieces, "O Israel," published in 1855. This was his first published work. Helmore also arranged for Arthur's music to be performed. One song was even performed at the Chapel Royal in St James's Palace.

Becoming a Mendelssohn Scholar

In 1856, the Royal Academy of Music gave the first Mendelssohn Scholarship to 14-year-old Arthur Sullivan. This scholarship gave him a year of training at the academy. His main teacher was John Goss. John Goss's own teacher had been a student of Mozart. Arthur also studied piano with William Sterndale Bennett and Arthur O'Leary. During this first year, Sullivan continued to sing solos with the Chapel Royal. This helped him earn a little spending money.

Sullivan's scholarship was extended for a second year. In 1858, the scholarship committee made an unusual decision. They extended his grant for a third year so he could study in Germany. He went to the Leipzig Conservatoire. There, Sullivan studied composition with Julius Rietz and Carl Reinecke. He also learned about counterpoint and piano. He learned about Mendelssohn's ideas. But he also learned about many other styles, including those of Schubert, Verdi, and Wagner. He visited a synagogue and was so impressed by the music that he remembered it for 30 years. He later used some of those musical ideas in his grand opera, Ivanhoe. He became friends with future theatre manager Carl Rosa and the famous violinist Joseph Joachim.

The academy renewed Sullivan's scholarship for a second year in Leipzig. For his third and final year there, his father found money for his living costs. The conservatoire also helped by not charging him fees. Sullivan finished his graduation piece in 1861. It was music for Shakespeare's play The Tempest. He later made some changes and additions to it. It was performed at the Crystal Palace in 1862, a year after he returned to London. The Musical Times newspaper said it was a sensation. He started to become known as England's most promising young composer.

Becoming a Famous Composer

Sullivan started his composing career with some big, important works. He also wrote hymns, popular songs, and other lighter pieces to earn money. His compositions alone were not enough to support him. So, between 1861 and 1872, he worked as a church organist, which he liked. He also taught music, which he disliked and stopped as soon as he could. He also arranged music for popular operas. He got an early chance to compose music for royalty. This was for the wedding of the Prince of Wales in 1863.

With The Masque at Kenilworth (1864), Sullivan began writing works for voices and orchestra. While working as an organist at the Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, he composed his first ballet, L'Île Enchantée (1864). His Irish Symphony and Cello Concerto (both 1866) were his only works in those styles. In the same year, his Overture in C (In Memoriam) was written. It was to remember his father, who had recently died. This piece became very popular. In June 1867, the Philharmonic Society performed his overture Marmion. A reviewer for The Times newspaper called it "another step forward" for England's most promising composer. In October, Sullivan traveled with George Grove to Vienna. They were looking for forgotten music by Schubert. They found old copies of symphonies and vocal music. They were especially excited to find the music for Rosamunde.

Sullivan's first try at an opera was The Sapphire Necklace (1863–64). The words were by Henry F. Chorley. This opera was never performed and is now lost, except for the overture and two songs. His first opera that still exists is Cox and Box (1866). It was first performed privately. Then it had charity performances in London and Manchester. Later, it was performed at the Gallery of Illustration. It ran for an amazing 264 shows! W. S. Gilbert, writing in Fun magazine, said the music was better than the story. Sullivan and F. C. Burnand were soon asked to write a two-act opera, The Contrabandista (1867). It was later changed and expanded into The Chieftain in 1894, but it was not as successful. One of Sullivan's early popular songs is "The Long Day Closes" (1868). Sullivan's last major work of the 1860s was a short oratorio called The Prodigal Son. It was first performed in Worcester Cathedral in 1869 and received much praise.

1870s: Working with Gilbert

Sullivan's most lasting orchestral work, the Overture di Ballo, was written for the Birmingham Festival in 1870. In the same year, Sullivan first met the poet and writer W. S. Gilbert. In 1871, Sullivan published his only song cycle, The Window, with words by Tennyson. He also wrote the first of many music scores for Shakespeare plays. He composed a dramatic cantata, On Shore and Sea, for the opening of the London International Exhibition. He also wrote the hymn "Onward, Christian Soldiers", with words by Sabine Baring-Gould. The Salvation Army adopted this hymn, and it became Sullivan's most famous hymn.

At the end of 1871, John Hollingshead, who owned London's Gaiety Theatre, asked Sullivan to work with Gilbert. They were to create a burlesque-style comic opera called Thespis. It was a Christmas show and ran until Easter 1872, which was a good run for that type of show. Gilbert and Sullivan then worked separately until they wrote three popular songs together in late 1874 and early 1875.

Sullivan's big works in the early 1870s included the Festival Te Deum (1872) and the oratorio The Light of the World (1873). He wrote music for plays like The Merry Wives of Windsor (1874) and Henry VIII (1877). He continued to compose hymns throughout this time. In 1873, Sullivan contributed songs to Burnand's Christmas show, The Miller and His Man.

In 1875, the manager of the Royalty Theatre, Richard D'Oyly Carte, needed a short play to go with another opera. Carte had conducted Sullivan's Cox and Box. He remembered that Gilbert had an idea for a story. So, Carte asked Sullivan to set it to music. The result was the one-act comic opera Trial by Jury. Trial was a surprise hit! It received great reviews and played for 300 performances in its first few seasons. The Daily Telegraph newspaper said the piece showed the composer's "great ability for writing lighter dramatic music." Other reviews praised how well Gilbert's words and Sullivan's music fit together. One reviewer wrote that it seemed "as though poem and music had proceeded simultaneously from one and the same brain." A few months later, another short comic opera by Sullivan opened: The Zoo. It was not as successful as Trial. For the next 15 years, Gilbert was Sullivan's only partner for operas. Together, they created twelve more operas.

Sullivan also wrote over 80 popular songs. Most of these were written before the end of the 1870s. His first popular song was "Orpheus with his Lute" (1866). A well-liked song was "Oh! Hush thee, my Babie" (1867). His most famous song is "The Lost Chord" (1877), with words by Adelaide Anne Procter. He wrote it while his brother Fred was very ill. The sheet music for his popular songs sold very well and was an important source of income for him.

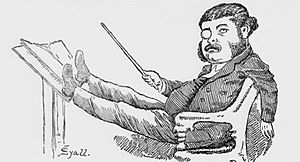

In this decade, Sullivan also conducted many concerts. He conducted the Glasgow Choral Union concerts (1875–77) and at the Royal Aquarium Theatre in London (1876). He was a Professor of Composition at the Royal Academy of Music. He was also appointed the first Principal of the National Training School for Music in 1876. He took this job unwillingly. He worried that it would take too much time away from his composing. He was right. He was not very effective in the role and resigned in 1881.

Sullivan's next opera with Gilbert, The Sorcerer (1877), ran for 178 performances. This was a success for the time. But H.M.S. Pinafore (1878), which came next, made Gilbert and Sullivan famous worldwide. Sullivan composed the cheerful music for Pinafore while suffering from severe pain from a kidney stone. Pinafore ran for 571 performances in London. This was the second-longest theatre run in history at that time. More than 150 unofficial productions quickly opened in America alone. Many reviews were positive. The Times noted that the opera was an early attempt to create a "national musical stage" free from foreign influences. The Times and other newspapers agreed that while the show was fun, Sullivan was capable of "higher art." They worried that light opera would hold him back. This criticism stayed with Sullivan throughout his career.

In 1879, Sullivan told a reporter from The New York Times the secret of his success with Gilbert. He said, "His ideas are as inspiring for music as they are funny. His songs... always give me musical ideas." Pinafore was followed by The Pirates of Penzance in 1879. It opened in New York and then ran in London for 363 performances.

Early 1880s: Knighthood and New Challenges

In 1880, Sullivan became the director of the Leeds Music Festival. This festival happened every three years. He had been asked to write a religious choral work for the festival. He chose a poem about the life of St Margaret of Antioch. The Martyr of Antioch was first performed at the Leeds Festival in October 1880. Gilbert helped adapt the story for Sullivan. In thanks, Sullivan gave Gilbert an engraved silver cup. Sullivan was not a very showy conductor. Some thought he was a bit dull. But Martyr was very popular and performed often. Other critics liked Sullivan's conducting. He had a busy conducting career alongside his composing. He always conducted the opening nights of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas.

Carte opened the next Gilbert and Sullivan opera, Patience, in April 1881. It was at London's Opera Comique. In October, Patience moved to the new, bigger, and modern Savoy Theatre. This theatre was built with the money from the previous Gilbert and Sullivan shows. All the rest of their operas were performed at the Savoy. They became known as the "Savoy operas." Iolanthe (1882) was the first new opera to open at the Savoy. It was Gilbert and Sullivan's fourth hit in a row. Sullivan, despite the financial security of writing for the Savoy, started to feel that writing comic operas was not important enough for his skills. After Iolanthe, Sullivan did not plan to write another work with Gilbert. But he lost a lot of money when his stockbroker went bankrupt in November 1882. So, he decided he needed to keep writing Savoy operas for money. In February 1883, he and Gilbert signed a five-year agreement with Carte. It said they had to produce a new comic opera with six months' notice.

On May 22, 1883, Queen Victoria made Sullivan a knight. This was for his "services... to the promotion of the art of music" in Britain. Many in the music world thought this meant he should stop writing comic operas. They believed a knight should only write serious works like oratorios or grand operas. Since he had just signed the five-year agreement, Sullivan felt trapped. The next opera, Princess Ida (1884), was their only three-act opera written in blank verse. It ran for a shorter time than their previous four hits. Sullivan's music for it was praised. When ticket sales slowed in March 1884, Carte gave the six months' notice for a new opera. Sullivan's close friend, the composer Frederic Clay, had recently had a stroke at 45. Sullivan thought about this, and his own kidney problems. He also wanted to write more serious music. He told Carte, "It is impossible for me to do another piece like those Gilbert and I have already written."

Gilbert had already started a new opera idea. In it, characters fell in love against their will after taking a magic lozenge. Sullivan wrote on April 1, 1884, that he was "at the end of my rope" with the operas. He said, "I have been constantly holding back the music so that not one word should be lost... I would like to set a story with human interest and realism. Where funny words would be in a funny situation, and if the situation was tender or dramatic, the words would be similar." In many letters, Sullivan said Gilbert's plot idea (especially the "lozenge") was too mechanical. He felt it was too similar to their earlier work, especially The Sorcerer. He kept asking Gilbert to find a new topic. The problem was finally solved on May 8. Gilbert suggested a plot that did not use any magic. The result was Gilbert and Sullivan's most successful work, The Mikado (1885). The show ran for 672 performances. This was the second-longest run for any musical theatre work at that time.

Later 1880s: More Success and New Dreams

In 1886, Sullivan composed his second and last big choral work of the decade. It was a cantata for the Leeds Festival, The Golden Legend. It was based on a poem by Longfellow. Besides the comic operas, this became Sullivan's most popular full-length work. It was performed hundreds of times during his life. At one point, he even stopped its performances for a while. He worried it was being performed too much. Only Handel's Messiah was performed more often in Britain in the 1880s and 1890s. It remained popular until about the 1920s. However, it is rarely performed now. It received its first professional recording in 2001. Music expert David Russell Hulme says the work influenced famous composers like Elgar and Walton.

Ruddigore followed The Mikado at the Savoy in 1887. It made money, but its nine-month run was not as long as most of the earlier Savoy operas. For their next piece, Gilbert suggested another version of the magic lozenge plot. Sullivan rejected it again. Gilbert finally suggested a more serious opera, and Sullivan agreed. Although it was not a grand opera, The Yeomen of the Guard (1888) gave him a chance to write his most ambitious stage work yet. As early as 1883, the music world had been pushing Sullivan to write a grand opera. In 1885, he told an interviewer that the "opera of the future" would combine the best parts of French, German, and Italian styles. He said, "I myself will try to produce a grand opera of this new style... Yes, it will be a historical work, and it is the dream of my life." After The Yeomen of the Guard opened, Sullivan again turned to Shakespeare. He composed music for Henry Irving's production of Macbeth (1888).

Sullivan wanted to create more serious works with Gilbert. He had not worked with any other writer since 1875. But Gilbert felt that the reaction to The Yeomen of the Guard was not strong enough to show that the public wanted even more serious works. He suggested that Sullivan should go ahead with his grand opera plan. But he should also keep writing comic works for the Savoy. Sullivan was not immediately convinced. He replied, "I have lost the liking for writing comic opera, and have serious doubts about my ability to do it." Nevertheless, Sullivan soon asked Julian Sturgis to write a grand opera story. He also suggested to Gilbert that he revive an old idea for an opera set in colourful Venice. The comic opera was finished first: The Gondoliers (1889). It was described as a peak of Sullivan's achievements. It was the last big Gilbert and Sullivan success.

1890s: New Collaborations and Final Works

The friendship between Gilbert and Sullivan had its biggest problem in April 1890. This happened during the run of The Gondoliers. Gilbert disagreed with Carte's financial records for the show. He especially objected to a charge for new carpet for the Savoy Theatre lobby. Gilbert believed this was a theatre maintenance cost that Carte should pay alone. Carte was building a new theatre for Sullivan's upcoming grand opera. Sullivan sided with Carte. He even signed a statement that had wrong information about old debts. Gilbert took legal action against Carte and Sullivan. He promised not to write for the Savoy again. So, their partnership ended badly. Sullivan wrote to Gilbert in September 1890 that he was "physically and mentally ill over this terrible business." He said he was shocked to see their names "in hostile opposition over a few miserable pounds."

Sullivan's only grand opera, Ivanhoe, was based on Walter Scott's novel. It opened at Carte's new Royal English Opera House on January 31, 1891. Sullivan finished the music too late for Carte's planned opening date. Costs grew, and Sullivan had to pay Carte a penalty of £3,000 for his delay. The show ran for 155 performances in a row. This was a very long run for a grand opera, and the music received good reviews. After this, Carte could not fill the new opera house with other opera productions and sold the theatre. Despite Ivanhoe's initial success, some people blamed it for the opera house's failure. It soon became forgotten. Herman Klein called it "the strangest mix of success and failure ever recorded in British opera history!" Later in 1891, Sullivan composed music for Tennyson's The Foresters. It did well in New York in 1892 but failed in London the next year.

Sullivan returned to comic opera. But because of the break with Gilbert, he and Carte looked for other writers. Sullivan's next piece was Haddon Hall (1892). The story was by Sydney Grundy, loosely based on the legend of Dorothy Vernon and John Manners. Although still comic, this work was more serious and romantic than most of the operas with Gilbert. It ran for 204 performances and was praised by critics. In 1895, Sullivan again wrote music for the Lyceum Theatre. This time it was for J. Comyns Carr's King Arthur.

With help from an intermediary, Sullivan's music publisher Tom Chappell, the three partners reunited in 1892. Their next opera, Utopia, Limited (1893), ran for 245 performances. It barely covered the costs of the grand production. However, it was the longest run at the Savoy in the 1890s. Sullivan disliked the leading lady, Nancy McIntosh, and refused to write another piece with her. Gilbert insisted she must be in his next opera. Instead, Sullivan teamed up again with his old partner, F. C. Burnand. The Chieftain (1894) was a heavily changed version of their earlier opera, The Contrabandista. It was not a success. Gilbert and Sullivan reunited one more time after McIntosh announced her retirement from the stage. This was for The Grand Duke (1896). It failed, and Sullivan never worked with Gilbert again. However, their earlier operas continued to be successfully revived at the Savoy.

In May 1897, Sullivan's full-length ballet, Victoria and Merrie England, opened at the Alhambra Theatre. It celebrated Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee. The work showed English history and culture, ending with the Victorian period. Its six-month run was a great achievement. The Beauty Stone (1898), with a story by Arthur Wing Pinero and J. Comyns Carr, was based on medieval morality plays. This collaboration did not go well. Sullivan wrote that Pinero and Comyns Carr were "talented and brilliant men, with no experience in writing for music." When he asked for changes to improve the structure, they refused. Also, the opera was too serious for the Savoy audiences. It was a critical failure and ran for only seven weeks.

In 1899, to help "the wives and children of soldiers and sailors" fighting in the Boer War, Sullivan composed music for a song. It was called "The Absent-Minded Beggar", with words by Rudyard Kipling. It became an instant hit and raised an amazing £300,000 for the fund. This came from performances and selling sheet music and related items. In The Rose of Persia (1899), Sullivan returned to his comic style. He wrote to a story by Basil Hood that mixed an exotic Arabian Nights setting with parts of The Mikado plot. Sullivan's musical score was well-liked. This opera became his most successful full-length collaboration apart from those with Gilbert. Another opera with Hood, The Emerald Isle, quickly began preparation. But Sullivan died before it was finished. The music was completed by Edward German and performed in 1901.

Death, Honours, and Lasting Influence

Sullivan's health was never very strong. From his thirties, his kidney disease often made him conduct while sitting down. He died of heart failure after an attack of bronchitis in his London flat on November 22, 1900. His Te Deum Laudamus, written hoping for victory in the Boer War, was performed after his death.

A monument to Sullivan was put up in the Victoria Embankment Gardens in London. It shows a weeping Muse (a goddess of inspiration). It has words from Gilbert's The Yeomen of the Guard: "Is life a boon? If so, it must befall that Death, whene'er he call, must call too soon." Sullivan wanted to be buried in Brompton Cemetery with his family. But Queen Victoria ordered him to be buried in St Paul's Cathedral. Besides being knighted, Sullivan received other honours. These included honorary Doctor of Music degrees from the Universities of Cambridge (1876) and Oxford (1879). He was also made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in France (1878). The Sultan of Turkey gave him the Order of the Medjidie (1888). He was also appointed a Member of the Fourth Class of the Royal Victorian Order (MVO) in 1897.

Sullivan's operas have often been changed and adapted. In the 19th century, they were made into dance pieces and foreign versions of the operas. Since then, his music has been used for ballets like Pineapple Poll (1951) and Pirates of Penzance – The Ballet! (1991). It has also been used in musicals like The Swing Mikado (1938) and The Hot Mikado (1939). His operas are still performed often. They are also parodied, copied, quoted, and imitated in many popular forms. These include comedy, advertising, films, and television. He has been shown in movies like The Story of Gilbert and Sullivan (1953) and Topsy-Turvy (2000). He is celebrated not only for writing the Savoy operas and his other works. He is also famous for his influence on the development of modern American and British musical theatre.

Personal Life

Sullivan never married, but he had close relationships with several women. In 1896, he proposed marriage to Violet Beddington, but she said no.

Hobbies and Family

Sullivan loved spending time in France, both in Paris and on the Riviera. There, he met European royalty. He also enjoyed playing games of chance at the casinos. He liked to host private dinners and parties at his home. These often featured famous singers and actors. In 1865, he joined Freemasonry. He became the Grand Organist of the United Grand Lodge of England in 1887 during Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee. Sullivan's talent and friendly personality helped him make many friends. These included people in music, like George Grove, and in high society. Sullivan enjoyed playing tennis. However, according to George Grossmith, he was not very good at it!

Sullivan was very close to his parents, especially his mother. He wrote to her regularly when he was away from London, until she died in 1882. Henry Lytton wrote that there was "never a more loving bond" than between Sullivan and his mother. She was a witty old lady and very proud of her son. Sullivan was also very fond of his brother Fred. He helped Fred's acting career whenever he could. He also loved Fred's children. After Fred died at 39, leaving his pregnant wife, Charlotte, with seven children under 14, Sullivan visited the family often. He became the children's guardian.

In 1883, Charlotte and six of her children moved to Los Angeles, California. The oldest boy, "Bertie", stayed with Sullivan. Sullivan paid for all the costs and gave the family a lot of financial support. A year later, Charlotte died. Her brother mostly raised the children. From June to August 1885, after The Mikado opened, Sullivan visited the family in Los Angeles. He took them on a sightseeing trip of the American west. For the rest of his life, and in his will, he helped Fred's children financially. He continued to write to them and cared about their education, marriages, and money matters. Bertie stayed with his Uncle Arthur for the rest of the composer's life.

Three of Sullivan's cousins, the daughters of his uncle John Thomas Sullivan, performed with the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company. These were Rose, Jane ("Jennie"), and Kate Sullivan. Rose and Jane used the stage name Hervey. Kate was a choir singer who joined a rival production of H.M.S. Pinafore. There, she got to play the main soprano role, Josephine, in 1879. Jennie was a D'Oyly Carte choir singer for 14 years. Rose played main roles in many of the shorter shows that played with the Savoy operas.

Sullivan's Music

Sullivan wrote 24 operas, 11 full orchestral works, 10 choral works and oratorios, 2 ballets, and music for several plays. He also composed over 70 hymns and anthems, more than 80 songs, and many piano and chamber pieces. He wrote operas, songs, and religious music throughout his career. His solo piano and chamber pieces are mostly from his early years. They usually sound like Mendelssohn's music. Except for his Imperial March (1893), his big orchestral concert works also came from early in his career.

Musical Influences

Music experts often say that Mendelssohn was the most important influence on Sullivan. Music for The Tempest and the Irish Symphony sounded very much like Mendelssohn to people at the time. Percy Young writes that Sullivan's early love for Mendelssohn stayed with him throughout his career. However, Benedict Taylor says that Schumann and Schubert were also big influences on Sullivan's orchestral works. From his first meeting with Rossini in Paris in 1862, Rossini's operas became a model for Sullivan's comic opera music.

As a young man, Sullivan's traditional music education led him to follow older composers. Later, he became more daring. Richard Silverman points out the influence of Liszt in later works. This included more complex harmonies. By the time of The Golden Legend, Sullivan sometimes did not even use a main musical key for the beginning. Sullivan did not like much of Wagner's opera style. But he based the overture to The Yeomen of the Guard on the beginning of Die Meistersinger. He called it "the greatest comic opera ever written." Meinhard Saremba writes that in his middle and later works, Sullivan was inspired by Verdi. This was true for small details and for the overall musical character of a piece. Examples include the "nautical feel of H.M.S Pinafore" and the "lightness of The Gondoliers."

How Sullivan Composed Music

Sullivan told an interviewer, Arthur Lawrence, "I don't use the piano when I compose. That would limit me terribly." Sullivan explained that he did not wait for inspiration. Instead, he would "dig for it." He would decide on the rhythm first. "I mark out the rhythm in dots and dashes," he said. "Only after I have completely decided on the rhythm do I start writing the actual notes." Sullivan's way of setting words to music was much more sensitive than other English composers of his time. His opera style tried to create a unique English blend of words and music. By using a traditional musical style, he could match Gilbert's clever words with his own clever music.

When composing the Savoy operas, Sullivan wrote the singing parts first. These were given to the actors. He, or an assistant, played a simple piano accompaniment during early rehearsals. He wrote the full orchestra music later. He did this after seeing how Gilbert would stage the show. He left the overtures until last. Sometimes he let his assistants compose them, based on his ideas. He would often add his own suggestions or corrections. Sullivan wrote the overtures for Thespis, Iolanthe, Princess Ida, The Yeomen of the Guard, The Gondoliers, The Grand Duke, and probably Utopia, Limited. Most of the overtures are a mix of tunes from the operas. They usually have three parts: fast, slow, and fast. The overtures for Iolanthe and The Yeomen of the Guard are written in a modified sonata form.

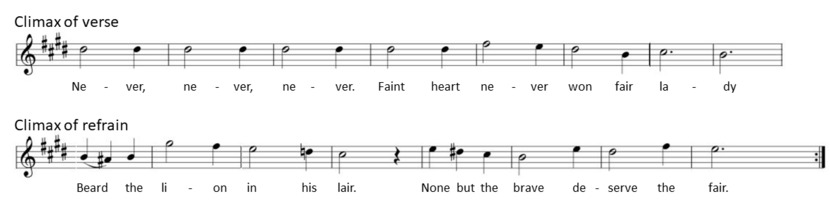

Melody and Rhythm

The Musical Times noted that Sullivan's tunes, especially in the comic operas, appealed to both musicians and everyday listeners. Famous European composers like Saint-Saëns and critic Eduard Hanslick thought highly of the Savoy operas. Hughes writes, "When Sullivan wrote what we call 'a good tune' it was nearly always 'good music' as well." He adds that few other composers, besides the very greatest, could say the same. Although his melodies came from rhythm, some of his themes might have been inspired by the instruments he chose or his harmony techniques.

In the comic operas, many songs have a verse and a chorus. Sullivan shaped his melodies to build to a peak in the verse. Then they would reach an overall peak in the chorus. Hughes gives "If you go in" (Iolanthe) as an example. He adds that Sullivan rarely reached the same level of excellence in instrumental works. This was because he did not have a writer to inspire him. Even with Gilbert, when the writer used a very regular rhythm, Sullivan often did the same. This sometimes led to simple, repeated musical phrases. Examples include "Love Is a Plaintive Song" (Patience) and "A Man Who Would Woo a Fair Maid" (The Yeomen of the Guard).

Sullivan preferred to write in major keys. This was true for most of the Savoy operas and even his serious works. Examples of his rare uses of minor keys include the long E minor melody in the first part of the Irish Symphony. Also, "Go Away, Madam" in Iolanthe and the execution march in The Yeomen of the Guard use minor keys.

Harmony and Counterpoint

Sullivan was trained in the classical style. He was not very interested in modern music. His early works used the usual harmonies of early 19th-century composers. These included Mendelssohn, Auber, Donizetti, and Schubert. Hughes says that the harmony in the Savoy works is made better by Sullivan's way of changing between keys. For example, in "Expressive Glances" (Princess Ida), he moves smoothly between E major, C sharp minor, and C major. Or in "Then One of Us will Be a Queen" (The Gondoliers), he writes in F major, D flat major, and D minor.

When someone criticized him for using consecutive fifths in Cox and Box, Sullivan replied, "if 5ths turn up it doesn't matter, so long as there is no offense to the ear." Both Hughes and Jacobs in Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians criticize Sullivan for using tonic pedals too much. These are usually in the bass (low notes). Hughes says this was due to "lack of effort or even plain laziness." Another Sullivan trademark criticized by Hughes is his repeated use of the augmented fourth chord during sad moments. In his serious works, Sullivan tried to avoid the harmony tricks he used in the Savoy operas. Because of this, according to Hughes, The Golden Legend is a "mix of harmonic styles."

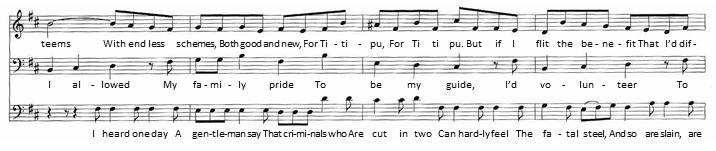

One of Sullivan's most famous techniques is what Jacobs calls his "'counterpoint of characters'." This is when different characters sing two seemingly separate tunes. These tunes then come together at the same time. He was not the first composer to combine themes this way. But it became almost "the trademark of Sullivan's operetta style." Sometimes the melodies were for solo singers, like in "I Am So Proud" (The Mikado). This song combines three different melodies. Other examples are in choruses. Typically, a graceful tune for the women is combined with a strong one for the men. Examples include "When the Foeman Bares his Steel" (The Pirates of Penzance) and "Welcome, Gentry" (Ruddigore). In "How Beautifully Blue the Sky" (The Pirates of Penzance), one theme is given to the chorus (in 2/4 time) and the other to solo voices (in 3/4).

Sullivan rarely composed fugues. Examples are from the "Epilogue" to The Golden Legend and Victoria and Merrie England. In the Savoy operas, he used fugal style to make fun of serious legal matters. This can be heard in Trial by Jury and Iolanthe. Less formal counterpoint is used in songs like "Brightly Dawns Our Wedding Day" (The Mikado).

Orchestration

Hughes concludes his chapter on Sullivan's orchestration: "In this very important part of the composer's art, he deserves to be called a master." Sullivan could play at least four orchestra instruments well. He was also a very skilled orchestrator. While he sometimes used too much grandeur for a full symphony orchestra, he was good at using smaller groups of instruments to great effect. Young writes that orchestra players generally enjoy playing Sullivan's music. "Sullivan never asked his players to do what was either unpleasant or impossible."

Sullivan's orchestra for the Savoy operas was typical for theatre orchestras of his time. It included flutes, oboe, clarinets, bassoon, horns, cornets, trombones, timpani, percussion, and strings. According to Geoffrey Toye, Sullivan's Savoy Theatre orchestras had a "minimum" of 31 players. Sullivan strongly argued for a larger orchestra. Starting with The Yeomen of the Guard, the orchestra was made bigger with a second bassoon and a second tenor trombone. He usually arranged each score almost at the last minute. He noted that the music for an opera had to wait until he saw the staging. This way, he could decide how much or how little to orchestrate each part of the music. For his large orchestral pieces, which often used very many instruments, Sullivan added more instruments. These included a second oboe, sometimes a double bassoon and bass clarinet, more horns, trumpets, tuba, and sometimes an organ or a harp.

One of the most recognizable things in Sullivan's orchestration is how he uses woodwind instruments. Hughes especially notes Sullivan's clarinet writing. He used all the different sounds of the instrument. He also really liked oboe solos. For example, the Irish Symphony has two long solo oboe parts one after the other. In the Savoy operas, there are many shorter examples. In the operas and concert works, another typical Sullivan touch is his love for pizzicato passages for the string sections. This is when strings are plucked instead of bowed. Hughes gives examples like "Kind Sir, You Cannot Have the Heart" (The Gondoliers) and "Free From his Fetters Grim" (The Yeomen of the Guard).

Musical References and Parodies

Throughout the Savoy operas, and sometimes in other works, Sullivan quotes or imitates well-known tunes. He also makes fun of the styles of famous composers. Sometimes he might have copied older composers without realizing it. Hughes mentions a Handelian influence in "Hereupon We're Both Agreed" (The Yeomen of the Guard). Rodney Milnes called "Sighing Softly" in The Pirates of Penzance "a song clearly inspired by – and indeed worthy of – Sullivan's hero, Schubert." Edward Greenfield found a tune in the slow part of the Irish Symphony to be "an outrageous copy" from Schubert's Unfinished Symphony. In early pieces, Sullivan used Mendelssohn's style in his music for The Tempest. He used Auber's style in his Henry VIII music and Gounod's in The Light of the World. Mendelssohn's influence is strong in the fairy music in Iolanthe. The Golden Legend shows the influence of Liszt and Wagner.

Sullivan used traditional musical forms. These included madrigals in The Mikado, Ruddigore, and The Yeomen of the Guard. He used glees in H.M.S. Pinafore and The Mikado. He also used the Venetian barcarolle in The Gondoliers. He used dance styles to fit the time or place of different scenes. These included gavottes in Ruddigore and The Gondoliers. He used a country dance in The Sorcerer and a nautical hornpipe in Ruddigore. He also used the Spanish cachucha and Italian saltarello and tarantella in The Gondoliers. Sometimes he used influences from further away. In The Mikado, he used an old Japanese war song. His trip to Egypt in 1882 inspired musical styles in his later opera The Rose of Persia.

Elsewhere, Sullivan wrote clear parodies. About the sextet "I Hear the Soft Note" in Patience, he told the singers, "I think you will like this. It is Dr Arne and Purcell at their best." In his comic operas, he followed Offenbach's lead in making fun of French and Italian opera styles. These included the styles of Donizetti, Bellini, and Verdi. Examples of his opera parodies include Mabel's song "Poor Wand'ring One" in The Pirates of Penzance. Also, the duet "Who Are You, Sir?" from Cox and Box and the whispered plans for elopement in "This Very Night" in H.M.S. Pinafore make fun of the conspirators' choruses in Verdi's Il trovatore and Rigoletto. The mock-patriotic "He Is an Englishman" in H.M.S. Pinafore and parts of the chorus in The Zoo make fun of British patriotic tunes like Arne's "Rule, Britannia!". The chorus "With Catlike Tread" from The Pirates makes fun of Verdi's "Anvil Chorus" from Il trovatore.

Hughes calls Bouncer's song in Cox and Box "a jolly Handelian parody." He also notes a strong Handelian feel to Arac's song in Act III of Princess Ida. In "A More Humane Mikado", at the words "Bach interwoven with Spohr and Beethoven", the clarinet and bassoon play a tune from Bach's Fantasia and Fugue in G minor. Sullivan sometimes used Wagnerian leitmotifs for both funny and dramatic effects. In Iolanthe, a special four-note tune is linked to the main character. The Lord Chancellor has a fugal (like a fugue) tune. The Fairy Queen's music makes fun of Wagner's heroines. In The Yeomen of the Guard, the Tower of London is brought to mind by its own tune. This use of the leitmotif technique is repeated and developed further in Ivanhoe.

Reputation and Criticism

Knighthood and Later Years

When Sullivan was knighted in 1883, serious music critics had more reasons to criticize him. They felt he should write more serious music.

Even Sullivan's friend George Grove wrote: "Surely the time has come when such a skilled master of voice, orchestra, and stage effect – a master, too, of so much true feeling – may use his talents for a serious opera on some lasting human or natural topic." Sullivan finally earned praise from critics with The Golden Legend in 1886. The Observer called it a "triumph of English art." The World called it "one of the greatest creations we have had for many years. Original, bold, inspired, grand in idea, in execution, in treatment, it is a composition which will mark an 'era' and which will carry the name of its composer higher on the wings of fame and glory... The effect of the public performance was unprecedented."

Hopes for a new direction were expressed in The Daily Telegraph's review of The Yeomen of the Guard (1888). This was Sullivan's most serious opera up to that point. The review said, "The music follows the story to a higher level. We have a true English opera, hopefully the first of many others. It possibly shows a step towards a national opera stage." Sullivan's only grand opera, Ivanhoe (1891), received mostly good reviews. However, J. A. Fuller Maitland, in The Times, had some doubts. He wrote that the opera's "best parts rise so far above anything else that Sir Arthur Sullivan has given to the world. They have such force and dignity that it is easy to forget the problems."

Even though the more serious music critics could not forgive Sullivan for writing music that was both funny and easy to enjoy, he was still "the nation's unofficial composer laureate." His obituary in The Times called him England's "most noticeable composer... the musician who had such power to charm all classes... The critic and the student found new beauties at every fresh listening. What... made Sullivan so popular, far above all other English composers of his day, was the tunefulness of his music. That quality made it... immediately recognized as a joyful contribution to the happiness of life... Sullivan’s name stood for music in England."

Reputation After His Death

In the ten years after his death, Sullivan's reputation dropped quite a bit among music critics. In 1901, Fuller Maitland disagreed with the generally praising tone of the obituaries. He asked, "Is there any case quite like that of Sir Arthur Sullivan? He began his career with a work that immediately showed him as a genius. Yet he only rarely reached that height throughout his life... It is because such great natural gifts – gifts greater, perhaps, than any English musician since... Purcell – were so very seldom used in work worthy of them." Edward Elgar, whom Sullivan had been especially kind to, defended Sullivan. He called Fuller Maitland's obituary "the dark side of music criticism... that terrible unforgettable event."

Fuller Maitland's followers, including Ernest Walker, also dismissed Sullivan. They called him "merely the idle singer of an empty evening." As late as 1966, Frank Howes, a music critic for The Times, criticized Sullivan for "lack of sustained effort... a basic lack of seriousness towards his art [and] inability to see the smugness, the sentimentality and commonness of the Mendelssohnian leftovers... to remain happy with the plainest and most obvious rhythms. This giving in to an easy talent excludes Sullivan from the ranks of the good composers." Thomas Dunhill wrote in 1928 that Sullivan's "music has suffered greatly from the strong attacks made on it by music professionals. These attacks have created a kind of barrier of prejudice around the composer. This barrier must be removed before his genius can be fairly judged."

Sir Henry Wood continued to perform Sullivan's serious music. In 1942, Wood held a Sullivan centenary concert at the Royal Albert Hall. But it was not until the 1960s that Sullivan's music, other than the Savoy operas, began to be widely performed again. In 1960, Hughes published the first full book about Sullivan's music. This book "noted his weaknesses (which are many) and did not hesitate to criticize his occasional lapses in good taste. It tried to see them in perspective against the wider background of his solid musicianship." The work of the Sir Arthur Sullivan Society, started in 1977, and books about Sullivan by musicians like Young (1971) and Jacobs (1986) helped people rethink Sullivan's serious music. The Irish Symphony had its first professional recording in 1968. Many of Sullivan's works without Gilbert have been recorded since then. New scholarly editions of more and more of Sullivan's works have been published.

In 1957, a review in The Times explained Sullivan's contributions to "the continued life of the Savoy operas." It said, "Gilbert's lyrics... become even more clever and lively when set to Sullivan's music... [Sullivan, too, is] a delicate wit. His tunes have a precision, a neatness, a grace, and a flowing melody."

Recordings

On August 14, 1888, George Gouraud introduced Thomas Edison's phonograph to London. This was at a press conference. It included playing a piano and cornet recording of Sullivan's "The Lost Chord." This was one of the first music recordings ever made. At a party on October 5, 1888, to show the technology, Sullivan recorded a speech for Edison. He said, in part: "I am amazed and somewhat scared by the result of this evening's experiments. Amazed at the wonderful power you have developed, and scared at the thought that so much awful and bad music may be recorded forever. But still, I think it is the most wonderful thing I have ever experienced. I congratulate you with all my heart on this wonderful discovery." These recordings were found in the Edison Library in New Jersey in the 1950s.

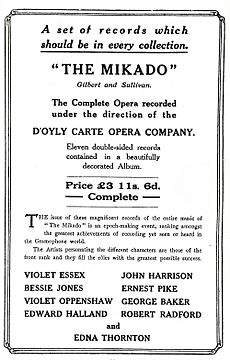

The first commercial recordings of Sullivan's music began in 1898. These were of individual songs from the Savoy operas. In 1917, the Gramophone Company (HMV) produced the first album of a complete Gilbert and Sullivan opera, The Mikado. They followed this with eight more. Electrical recordings of most of the operas were released by HMV and Victor from the 1920s. These were overseen by Rupert D'Oyly Carte. The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company continued to make recordings until 1979. After the copyrights ended, other opera companies made recordings. These included Gilbert and Sullivan for All and Australian Opera. Sir Malcolm Sargent and Sir Charles Mackerras each conducted audio sets of several Savoy operas. Since 1994, the International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival has released professional and amateur CDs and videos of its shows. Ohio Light Opera has recorded several of the operas in the 21st century.

Sullivan's works not from the Savoy operas were rarely recorded until the 1960s. A few of his songs were recorded in the early 1900s. These included versions of "The Lost Chord" by Enrico Caruso and Clara Butt. The first of many recordings of the Overture di Ballo was made in 1932. The Irish Symphony was first recorded in 1968. Since then, much of Sullivan's serious music and his operas without Gilbert have been recorded. These include the Cello Concerto by Julian Lloyd Webber (1986). Also, The Rose of Persia (1999), The Golden Legend (2001), Ivanhoe (2009), and The Masque at Kenilworth and On Shore and Sea (2014) have been recorded. In 2017, Chandos Records released an album called Songs. It includes The Window and 35 individual Sullivan songs. Mackerras's Sullivan ballet, Pineapple Poll, has been recorded many times since its first performance in 1951.

See Also

In Spanish: Arthur Sullivan para niños

In Spanish: Arthur Sullivan para niños

- List of compositions by Arthur Sullivan

- People associated with Gilbert and Sullivan

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |