Vincenzo Bellini facts for kids

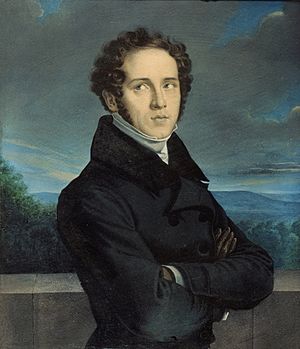

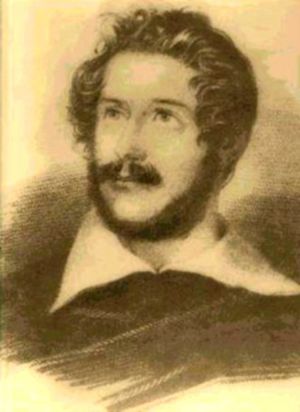

Vincenzo Bellini (born November 3, 1801 – died September 23, 1835) was a famous Italian opera composer. People called him "the Swan of Catania" because of the beautiful, long, flowing melodies in his music. Years later, another great composer, Giuseppe Verdi, praised Bellini's melodies, saying no one else had created such long, lovely tunes before.

Most of what we know about Bellini's life comes from letters he wrote. Many of these letters were sent to his good friend Francesco Florimo, whom he met when they were students in Naples. Other letters from friends and business partners also tell us about his life.

Bellini wrote many successful operas. Il pirata in 1827 was an early hit. Then came I Capuleti e i Montecchi in 1830 and La sonnambula in 1831, which were huge triumphs. His opera Norma in 1831 took a little longer to become popular but is now very famous. His last big success was I puritani in Paris in 1835. Today, you can still see Il pirata, Capuleti, La sonnambula, Norma, and I puritani performed regularly around the world.

After his first success in Naples, Bellini spent most of his short life away from Sicily and Naples. He lived and composed in Milan and other parts of Northern Italy. After a visit to London, he created his final masterpiece, I puritani, in Paris. Just nine months later, Bellini passed away in Puteaux, France, at the young age of 33.

Template:TOC limit=3

Contents

- Early Life in Catania

- Musical Education in Naples

- Beginning His Career

- Life in Northern Italy

- Major Achievements

- London: April to August 1833

- Paris: August 1833 to January 1835

- Paris: January to September 1835

- Bellini, Romanticism, and Melodrama

- Personal Life and Relationships

- Complete Works of Bellini

- See also

Early Life in Catania

Vincenzo Bellini was born in Catania, which was part of the Kingdom of Sicily at the time. He was the oldest of seven children in a very musical family. His grandfather, Vincenzo Tobia Bellini, was an organist and teacher in Catania. Vincenzo's father, Rosario, was also a musician.

Some stories say that Bellini was a child genius. An old handwritten history in Catania claims he could sing an opera song at 18 months old! It also says he started learning music theory at two and piano at three. By age five, he could play "marvelously." This document even states that he wrote his first five pieces at just six years old. However, Bellini's biographer, Herbert Weinstock, thinks some of these stories might just be myths.

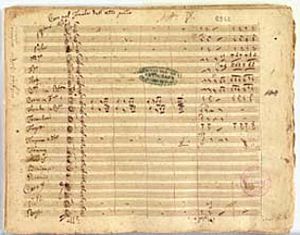

After 1816, Bellini lived with his grandfather and began his first music lessons. Soon, he started writing his own music. These early works included nine Versetti da cantarsi il Venerdi Santo, many of which used texts by Pietro Metastasio.

By 1818, Bellini had written several orchestral pieces and two settings of the Mass Ordinary. These pieces still exist today and have even been recorded.

Bellini was ready for more advanced studies. Wealthy students would move to Naples for this. Even though his family wasn't rich, Bellini's talent was clear. He got a big break when the Duke and Duchess of San Martino e Montalbo, who were important officials in Catania, encouraged him. They helped him ask the city for money to support his music studies. In May 1819, the city agreed to give him a four-year scholarship to study at the Real Collegio di Musica di San Sebastiano in Naples. He left Catania in July with letters of introduction to important people. Bellini lived in Naples for the next eight years.

Musical Education in Naples

The Conservatorio di San Sebastiano in Naples was a government-run music school. Students wore uniforms and followed a strict daily schedule. They had classes in main subjects, singing, and instruments, plus basic education. Their days were long, starting early in the morning and ending late at night. Bellini was a bit older than most new students, but he submitted ten pieces of music that showed his great talent. He did need to work on some of his techniques, though.

The school focused on older Italian composers like Pergolesi and Paisiello, and orchestral works by Haydn and Mozart. They didn't focus as much on newer composers like Rossini. Bellini's first teacher was Giovanni Furno, and he learned counterpoint from Giacomo Tritto. The school's artistic director was the famous opera composer, Niccolò Antonio Zingarelli.

During his time at the Collegio, Bellini met Francesco Florimo, who became his lifelong friend. Other students who later became opera composers included Francesco Stabile and the Ricci brothers, Luigi and Federico. Saverio Mercadante was also a student there.

Bellini also met Gaetano Donizetti, another important composer. Donizetti's opera La zingara was a big success in Naples. Bellini was very impressed by Donizetti's music and by the man himself.

First Compositions in Naples

Bellini did very well in his studies. In January 1820, he passed his exams and earned an annual scholarship. This meant the money from Catania could now help his family. He continued to succeed and, as part of his scholarship, he sent a Messa di Gloria in A Minor to Catania. It was performed there in October.

During his years of study in Naples, Bellini also wrote two other Mass settings and two settings of the Salve Regina. He also composed a short two-movement Oboe Concerto in E-flat in 1823, which has been recorded by the Berlin Philharmonic.

By January 1824, Bellini became a "primo maestrino," meaning he could tutor younger students and had his own room. He also got to visit the Teatro di San Carlo on Thursdays and Sundays. There, he saw his first opera by Rossini, Semiramide. Bellini was amazed by Rossini's music. He even told his friends, "After Semiramide, it's useless for us to try and achieve anything!"

A personal challenge also came up for Bellini. He fell in love with Maddalena Fumarolis, whose family he tutored in music. Her parents found out and forbade them from seeing each other. Bellini was determined to get their permission to marry her. Some people believe this desire pushed him to write his first opera.

Adelson e Salvini

In late 1824, Bellini was asked to compose an opera for the conservatory's small theater. This became Adelson e Salvini, a "half-serious" opera with words by Andrea Leone Tottola. It premiered between January and March 1825, with an all-male cast of fellow students. It was so popular that it was performed every Sunday for a year!

After this success, Bellini, who had been away from home for six years, visited his family in Catania. He returned to Naples by late 1825 to work on a new opera for one of the royal theaters.

Beginning His Career

After Adelson e Salvini, Bellini started making changes to it, hoping it would be performed by Domenico Barbaja, the manager of the Teato di San Carlo. However, it seems this revised version was never performed.

In late 1825, Bellini began working on his first opera to be produced professionally. The Conservatory had a rule that talented students should write a cantata or a one-act opera for a special gala. Bellini managed to get permission to write a full-length opera instead. He also got to choose his own writer for the words (libretto), instead of using the official theater poet. Barbaja, the theater manager, benefited greatly from this, finding a promising young composer with a small investment.

Bianca e Gernando

Bellini chose Domenico Gilardoni, a young writer, to create his first libretto. It was called Bianca e Fernando, based on a play set in Sicily.

However, the title had to be changed because "Ferdinando" was the name of the heir to the throne, and that name couldn't be used on a royal stage. After some delays, the opera, now called Bianca e Gernando, premiered at the Teatro di San Carlo on May 30, 1826. It was a huge success! Even King Francesco I broke tradition by applauding, which was not usually done when royalty was present. Donizetti also attended and wrote that it was "beautiful, beautiful, beautiful." Bellini's music was highly praised.

Within nine months, in February 1827, Domenico Barbaja offered Bellini a contract to write an opera for La Scala in Milan, a very famous opera house.

Life in Northern Italy

From 1827 to 1833, Bellini mostly lived in Milan. He didn't hold any official job at an opera company. He earned his living only from his compositions, for which he could ask for higher than usual fees.

When he arrived in Milan, he met Antonio Villa of La Scala and composer Saverio Mercadante. Mercadante introduced him to Francesco and Marianna Pollini, an older couple who took Bellini under their wing.

Bellini also met the librettist Felice Romani. Romani suggested the story for Bellini's first project, Il pirata. Bellini liked the idea because the story had "passionate and dramatic situations" and "Romantic characters" which were new for opera at the time. This started a strong working relationship between Bellini and Romani. Romani wrote the words for six of Bellini’s next operas. Bellini admired Romani's beautiful and elegant writing.

While in Milan, Bellini became friends with people in high society. He also stayed with friends, the Cantù and Turina families. He began a relationship with Giuditta Turina in 1828.

The four years Bellini spent in Northern Italy (1827-1831) were very productive. He created four great operas: Il pirata, I Capuleti e i Montecchi, La sonnambula, and Norma.

Il pirata for Milan

Bellini and Romani started working on Il pirata in May 1827. By August, Bellini was writing the music. He knew his favorite tenor, Giovanni Battista Rubini, and the soprano Henriette Méric-Lalande would sing in it. Both had starred in his earlier opera, Bianca. The cast also included the famous bass-baritone Antonio Tamburini. Rehearsals were sometimes difficult. Bellini wanted Rubini to act more expressively, not just sing beautifully. Bellini's advice worked, and the audience loved Rubini's performance.

The premiere on October 17, 1827, was an instant success. It was performed 15 times to full houses. For Rubini, it was a defining performance. After Milan, Il pirata was also very successful in Vienna and Naples. By this time, Bellini was becoming famous internationally.

Bianca Revised

After Il pirata, Bellini stayed in Milan, hoping for another opera contract. He received an offer from Genoa in January 1828 for a new opera. Since he didn't know which singers would be available, he waited. When no other offers came, he accepted Genoa's offer in February. It was too late to write a brand new opera, so he suggested revising Bianca e Gernando. This time, it was called Bianca e Fernando, as there was no royal named Fernando in Genoa. Romani rewrote much of the libretto, making about half of it new. Bellini then changed the music to fit the voices of the new singers, Adelaide Tosi and Giovanni David.

Bellini had some disagreements with Tosi about changes to her songs, but he stuck to his ideas. He was right, as the audience loved the opera, especially the second act. The first performance in Genoa was even more successful than in Naples, with 21 performances in total. However, some critics were not as positive as the audience.

After Bianca

Bellini returned to Milan with no specific plans. He had some issues with Barbaja, the theater manager, but eventually signed a contract to write a new opera for Milan's Carnival season. This time, he would receive 1,000 ducati, much more than the 150 ducati for his first opera.

La straniera for Milan

For La straniera, Bellini earned enough money to live solely from composing. This new opera became an even bigger success than Il pirata. Bellini and Romani decided to base the story on a French novel called L'étrangère. The premiere was planned for December 26, but Romani fell ill, causing delays. Bellini also worried about finding a good tenor. He eventually found Domenico Reina, whom he described as having a beautiful voice and great acting skills.

Romani recovered, but the libretto arrived slowly. Bellini worked hard, sometimes struggling to find inspiration for the music. One time, Romani had to rewrite a song's text three times before Bellini was happy. Bellini wanted words that were "a prayer, an imprecation, a warning, a delirium..." Romani finally got it right.

La straniera premiered on February 14, 1829. It was a huge success. The newspaper praised Bellini as "a modern Orpheus" for his beautiful melodies. Bellini wrote to Romani, saying, "the thing went as we never had imagined it. We were in seventh heaven." However, some people criticized the opera's new style and harmonies.

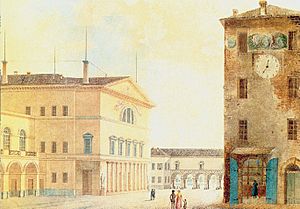

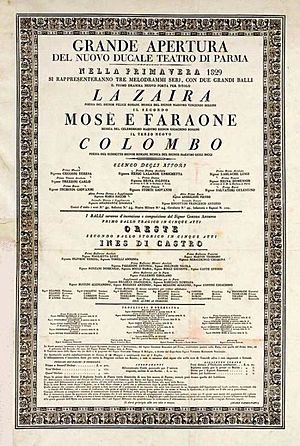

Zaira: A Setback in Parma

Bellini was asked to write an opera for the opening of the new Teatro Ducale (now the Teatro Regio) in Parma. He and Romani chose Voltaire's play Zaïre as the subject for Zaira.

This opera was Bellini's first major setback. Some say Bellini wasn't very enthusiastic about the project. Others believe it was because Parma loved Rossini's music more. Also, Bellini was often seen in cafes instead of composing, and Romani admitted in the libretto that he had rushed the writing. Both composer and librettist delayed their work. Bellini arrived in Parma only 56 days before the opening, and some singers arrived even later.

The premiere on May 16, 1829, was not well-received. The music was considered weak, though some parts were liked. The singers were applauded, but Bellini received little praise. Zaira was performed only eight times and then disappeared until 1976.

Major Achievements

After Zaira's poor reception, Bellini returned to Milan. He learned that his 85-year-old grandfather had passed away. He didn't have a contract for a new opera, but there was a chance to work with the Teatro La Fenice in Venice.

Giovanni Pacini, another composer from Catania, was also in Milan and had a successful opera. Bellini saw him as a rival. Pacini received offers for operas in Turin and Venice. He accepted both, but the Venice theater manager had a backup plan: if Pacini couldn't fulfill the contract, it would go to Bellini.

Bellini focused on bringing back his opera Il pirata at the Teatro Canobbiana in Milan. It was a huge success again, with 24 performances.

During this time, Gioachino Rossini visited Milan. He saw Il pirata and met Bellini. The two composers liked each other, and later in Paris, they became very close friends.

In the autumn, Bellini received a firm contract for a new opera in Venice. He arrived in Venice in mid-December.

I Capuleti e i Montecchi: Venice, March 1830

Bellini was told that Pacini might not be able to stage an opera in Venice, so Bellini's contract would become active on January 14. He accepted the offer on January 5, agreeing to set Romani's libretto for Giulietta Capellio. He asked for 45 days between getting the libretto and the first performance.

Romani arrived in Venice by January 20. He had already reworked much of his earlier libretto for another opera called Giulietta e Romeo. Bellini and Romani worked together under great pressure. Bellini fell ill due to the bad weather and tight schedule. They agreed on changes to the libretto and a new title: I Capuleti e i Montecchi. Bellini also reused some music from Zaira and from Adelson e Salvini. The role of Romeo was written for Giuditta Grisi, and Giulietta was sung by Rosalbina Caradori-Allan.

The premiere on March 11, 1830, was a great success for Bellini. It was performed eight times before the season ended. A local newspaper reported that it created as much excitement in Venice as La straniera had in Milan.

Bellini knew he was becoming famous. He wrote on March 28, "My style is now heard in the most important theatres in the world... and with the greatest enthusiasm."

Before leaving Venice, Bellini was offered another contract for the 1830–31 Carnival season. He also received an offer from Genoa, but he had to turn it down because it was for the same time.

Later that year, Bellini prepared a version of Capuleti for La Scala, which premiered on December 26. He lowered Giulietta’s part for the mezzo-soprano Amalia Schütz Oldosi.

La sonnambula: Milan, March 1831

After the Capuleti performances, Bellini returned to Milan. He was able to get a very good contract to write for the Teatro Carcano in Milan. He would earn almost twice as much as before. He also secured contracts for Norma at La Scala and Beatrice di Tenda for La Fenice.

Bellini then suffered from an illness that would return after each opera and eventually cause his death. He described it as a "tremendous inflammatory gastric bilious fever." He was cared for by his friends, Francesco and his wife, who loved him "more than a son."

After recovering, Bellini went to stay near Lake Como. He needed to choose a subject for his next opera. It was decided that Giuditta Pasta, a famous singer, would be the main artist. She also owned a house near Como, so Romani traveled to meet her and Bellini.

Attempts to Create Ernani

By July 15, they decided to adapt Victor Hugo's play, Hernani. However, the play's political themes were risky due to strict censorship in Austrian-controlled Lombardy. Also, it was unclear if Pasta wanted to sing a male role. Romani promised to start the libretto but instead wrote one for Donizetti's Anna Bolena. By late November, nothing had been written for Ernani.

On January 3, 1831, Bellini wrote that he was no longer composing Ernani because the police would have required too many changes. Instead, Romani was writing La sonnambula, ossia I Due Fidanzati Svizzeri, which needed to be on stage by February 20.

La sonnambula Replaces Ernani

Romani's libretto for La sonnambula was based on a French ballet. With its country setting and story, La sonnambula became another huge success for Bellini in Milan.

The main role of Amina (the sleepwalker) is very difficult to sing, requiring perfect control of trills and fancy vocal techniques. It was written for Giuditta Pasta, who was known for her wide vocal range.

Bellini reused some music he had started for Ernani in La Sonnambula. This was common for composers at the time.

The opera premiered on March 6, 1831, at the Teatro Carcano. Its success was due to Romani's improved libretto and the combined experience of both Bellini and Romani.

After its Milan premiere, the opera was performed in London on July 28, 1831, and in New York on November 13, 1835. During Bellini's lifetime, another famous singer, Maria Malibran, also became well-known for singing the role of Amina.

Norma: Milan, December 1831

After La sonnambula's success, Bellini and Romani began working on their next opera for La Scala, which would feature Giuditta Pasta. By summer, they chose Norma, based on a French play.

For the roles of Adalgisa and Pollione, La Scala hired Giulia Grisi, Giuditta's sister, and the famous tenor Domenico Donzelli. Romani finished much of the libretto by the end of August, allowing Bellini to start composing in September. Pasta's singing and acting skills were amazing; she had just created the very different role of Amina in La sonnambula.

As the year went on, Bellini became worried. A cholera outbreak in Austria made him fear it would spread to Italy and close the theaters. He wrote to Florimo that he was composing without much enthusiasm because he thought the cholera would arrive.

He also received an offer to compose for the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. Bellini set strict conditions, refusing to work with a soprano he thought was "below mediocrity." He also demanded a higher fee than he received from La Scala.

Norma was finished by late November. Bellini then had to deal with music piracy. Some publishers were illegally copying his vocal scores, orchestrating them, and selling them as full orchestral scores to theaters. Bellini published a notice in newspapers to warn these "pirates."

Rehearsals began on December 5. Pasta initially didn't want to sing the famous aria Casta diva, feeling it didn't suit her voice. But Bellini convinced her to keep trying, and after a week, she mastered it and admitted her mistake. On opening night, December 26, 1831, the opera was met with "chill indifference." Bellini wrote to Florimo, "Fiasco! Fiasco! Solemn fiasco!"

Bellini tried to explain the reasons for the audience's reaction. He mentioned the singers' tiredness and how some parts of the opera didn't please the audience or even himself. However, he noted that most of the second act was very effective. The second performance was more successful. He also believed some negative reactions were caused by a newspaper owner and a wealthy woman who supported another composer. Despite the initial reception, Norma was performed 39 times that season and became more popular over time. Bellini left Milan for Naples and Sicily in January 1832. That year, he did not write a new opera.

Naples, Sicily, Bergamo: January to September 1832

Bellini traveled to Naples, possibly stopping in Rome to see Giuditta Turina. Giuditta and her brother also went to Naples, where she finally met Florimo. Bellini stayed in Naples for six weeks.

He was busy during this time, spending time with Turina, visiting the conservatory, and meeting students and his old teacher, Zingarelli. He also attended a performance of Capuleti at the San Carlo, where King Ferdinand II led the applause for him. Bellini received a warm welcome from the people of Naples.

Bellini then traveled to Messina with Florimo, where his family greeted him. They attended a performance of Il pirata, and Bellini was cheered loudly.

On March 3, Bellini arrived in Catania to a civic welcome. The city authorities and citizens celebrated him with a concert featuring music from La sonnambula and Il pirata. The city's main theater, the Teatro Massimo Bellini, was later named in his honor. After a month, Bellini and Florimo left for Palermo, where he received another "royal welcome." He met Filippo Santocanale and his wife. Despite bad weather, they had a good time, but Bellini wanted to return to Naples to be with Giuditta Turina. They reached Naples on April 25.

Bellini wrote to Santocanale, saying he would accept a contract from La Fenice. He had forgotten the exact terms he demanded, so he asked Giuditta Pasta's husband to send him a letter where he had revealed the offer.

The couple reached Rome on April 30. Some people think Bellini composed a one-act opera called Il fu ed it sara (The Past and the Present) for a private performance there, but no music from it has been found. They then traveled to Florence, where Bellini saw a performance of La sonnambula that he found "quite unrecognizable." He also told his publisher that he had finalized the contract with Lanari for an opera in Venice, where he would have the "divine Pasta" as a singer. He would also receive 100% of the rental rights for the scores.

Within a few days, Bellini was in Milan. He wrote to Santocanale that he was looking for a good subject for his new opera for Venice. In August, he went to Bergamo for a successful production of Norma with Pasta.

After the Bergamo success, Bellini spent a few days with Turina. By mid-September, he was back in Milan, eager to meet Romani to choose the subject for the next opera for La Fenice. It was also agreed that Norma would open the season before the new opera.

Beatrice di Tenda: Venice 1833

For Beatrice di Tenda, Bellini needed a strong female character for Pasta. He and Romani met to choose a subject. Romani had to search through many possible sources and became frustrated. By October 6, they agreed on Cristina regina di Svenzia. However, a month later, Bellini wrote to Pasta that the subject had changed to Beatrice di Tenda, based on a play by Carlo Tedaldi-Fores. Bellini had a hard time convincing Romani, but he succeeded. He hoped Romani would quickly prepare the first act.

Bellini's hope for Romani's speed was a mistake. Romani had too many other commitments. Nothing happened in November. Bellini arrived in Venice in early December and focused on rehearsals for Norma. The lack of new verses for Beatrice, which was supposed to be staged in February, forced Bellini to complain to the governor of Venice, who then contacted Romani through the police. Romani finally arrived in Venice on January 1, 1833. He worked on Bellini's libretto, but other composers like Donizetti were also angry about delays from Romani.

When Norma opened on December 26, it was a success only because of Pasta. The other singers were not very good, and Bellini worried about Beatrice. He complained to Santocanale on January 12 about the short time he had to write the opera, blaming Romani for being lazy. Their relationship quickly worsened. However, by February 14, Bellini reported that he had only "another three pieces of the opera to do" and hoped to open on March 6.

Bellini had to delete parts of the libretto and some music to finish the opera in time. The theater manager, Lanari, filled the program with older works to give Bellini more time. This left only eight days for Beatrice before the season ended. Not surprisingly, the audience was not enthusiastic on opening night, March 16. Romani even included a note in the libretto asking for "the reader's full indulgence." However, the next two performances drew large crowds. Bellini felt his opera "was not unworthy of her sisters."

The Break with Romani

Before the premiere, a Venetian newspaper published a letter complaining about the delay of Beatrice. The editor replied, saying Bellini and Romani were trying to achieve perfection. After the first performance, many negative letters about Beatrice appeared. Then, a pro-Bellini letter, signed "A friend of M. Bellini," shifted the blame to Romani, explaining how late the libretto was delivered. On April 2, Romani responded, blaming Bellini for not deciding on a subject and complaining that his work was "touched up in a thousand ways" for London audiences.

The argument continued in Milanese newspapers. "Pietro Marinetti" defended Bellini, criticizing Romani's harsh tone. Romani responded again, and the editor of L'Eco expressed disapproval of the public dispute.

The Relationship Begins to Be Repaired

Bellini was invited to write a new opera for Naples but declined due to his Paris commitments. He suggested May 1835 might be possible. Florimo tried to persuade him, mentioning that the famous singer Malibran would be in Naples in January 1835.

It seems Bellini no longer held a grudge against Romani. Through a mutual friend, Romani expressed interest in being friends again. Bellini wrote back, "Tell my dear Romani that I still love him even though he is a cruel man." He wondered if Romani ever thought about him, saying he constantly talked about Romani. He ended with, "Give him a kiss for me." Bellini then asked Florimo if Romani felt the same way. Romani apparently did, as Bellini later wrote to Romani, suggesting they "draw a veil over everything that happened." He said he couldn't come to Milan but might in January 1835 after I puritani. He ended by saying if he didn't hear back, he wouldn't write again. Romani replied, and Bellini wrote a very friendly letter to him on October 7, 1834, saying, "It seemed impossible to exist without you," and "Write for me alone: only for me, for your Bellini."

Sadly, Bellini died within a year of writing that letter. The two men never met again.

London: April to August 1833

After leaving Venice on March 26, Bellini spent time with Mrs. Turina in Milan. He left many of his belongings with her, planning to return by August.

Bellini and his opera group, including Pasta, were contracted to perform in London by the King's Theatre manager, Pierre-François Laporte. On his way, Bellini stopped in Paris and talked with Dr. Louis Véron, the director of the Paris Opéra, about writing a French opera. He planned to focus on this after returning from London.

When Bellini arrived in London by April 27, he was already well-known. Many of his operas had been performed there. He was seen at a performance of Rossini's La Cenerentola with other famous musicians like Maria Malibran, Felix Mendelssohn, and Niccolò Paganini. His operas Il pirata, La sonnambula, and La straniera had already been presented in London.

Separately, Maria Malibran was about to make her London debut in La sonnambula at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane on May 1. It was an English version with Bellini's music adapted.

As the opera season continued, Bellini was invited to many social events. His fame was now secure, especially after La sonnambula. The premiere of Norma on June 21, with Pasta in the main role, was a huge triumph. London newspapers also gave favorable reviews. I Capuleti e i Montecchi premiered in London in late July. After his contract ended, Bellini left for Paris by mid-August.

Paris: August 1833 to January 1835

When Bellini arrived in Paris in mid-August 1833, he planned to stay only about three weeks. His main goal was to continue talks with the Opéra. Although he didn't reach an agreement with the Opéra, the Théâtre-Italien made him an offer. Bellini accepted because the pay was better than in Italy, the company was magnificent, and he could stay in Paris at someone else's expense.

The managers of the Italien offered him a seat at their theater. They told him that Grisi, Unger, and Rubini would sing Pirata in October and Capuleti in November. Bellini settled into a new, small apartment and wrote to Florimo, asking him to send some of his furniture from Milan.

Bellini quickly joined the fashionable Parisian social scene, especially the salon run by Princess Belgiojoso. Her salon was a meeting place for Italian revolutionaries and artists. Bellini likely met Count Carlo Pepoli there, as well as famous writers like Victor Hugo and Heinrich Heine, and musicians like Luigi Cherubini.

Bellini admitted to Florimo in March 1834 that he had been having too much fun in London and Paris. However, in January 1834, he signed a contract to write a new opera for the Théâtre-Italien, to be presented at the end of the year. He also received an offer from Naples for an opera, but he declined due to his Paris commitment.

Bellini became worried in April 1834 when he learned that Donizetti would also be composing for the Théâtre-Italien that season. Bellini thought this was a plot by Rossini. He wrote long letters to Florimo expressing his frustrations.

However, after the great success of Puritani, Bellini realized his fears were unfounded. He explained how he had worked to become friends with Rossini, seeking his advice. He wrote that he had "tamed Rossini's hatred" and finished his work, which brought him much honor. Throughout the year, he wrote to Florimo about Rossini's increasing support and even love for him.

While composing Puritani, Bellini suffered another bout of "gastric fever," an illness that often returned with warm weather.

I puritani: January 1834 to January 1835

After signing the contract for a new opera, Bellini looked for a suitable subject. In March 1834, he wrote to Florimo that he was struggling to find a plot that would work for Paris and the singers.

He was working with Count Pepoli, an Italian exile who had not written for opera before. Writing the libretto and working with Bellini was difficult. Bellini also reported a period of illness. However, by April 11, he wrote that he was well and had chosen the story for his Paris opera. It was about the time of Cromwell and the English Civil War. He mentioned that his favorite singers—Giulia Grisi, Rubini, Tamburini, and Lablache—would be available for the main roles. He planned to start writing the music by April 15.

The chosen story was a play performed in Paris called Têtes Rondes et Cavalieres (Roundheads and Cavaliers). Bellini helped Pepoli by creating a scenario of 39 scenes, simplifying the original play and reducing the number of characters. He also gave them more Italian-sounding names.

While working on I Puritani, Bellini moved to Puteaux, a short distance from Paris, to stay with an English friend, Samuel Levys. He hoped to finish his opera more carefully there. He urged Pepoli to bring the first act of the opera so they could finish discussing it.

By late June, much progress had been made. Bellini wrote to Alessandro Lanari, director of the Royal Theatres of Naples, that the first act of Puritani was finished. He expected to complete the opera by September so he could then write for Naples. Bellini set strict terms for the Naples contract, but he decided not to negotiate until he saw how successful Puritani would be.

By September, he was polishing the opera. He was happy with Pepoli's verses, especially a "very beautiful trio for the two basses and La Grisi." By mid-December, he had submitted the score for Rossini's approval. Rehearsals were planned for late December/early January. The dress rehearsal on January 20, 1835, was attended by many important people who were very enthusiastic. The premiere, delayed by two days, took place on January 24, 1835. The opera became "the rage of Paris" and was performed 17 times until the season ended on March 31.

Paris: January to September 1835

After I puritani's success, Bellini received two honors. King Louis-Philippe named him a chevalier of the Légion d'honneur, and King Ferdinand II in Naples awarded him the cross of the "Order of Francesco I." Bellini dedicated I puritani to the Queen of the French, Queen Marie-Emélie. Personally, Bellini was sad that he hadn't seen Florimo in a long time. He invited Florimo to Paris many times, but Florimo didn't come. Bellini eventually wrote, "I'll no longer ask for reasons, and I'll see you when I see you." He then tried to persuade his uncle, Vincenzo Ferlito, to visit, but without success.

In 1834, Bellini had agreed to present three operas in Naples, including revisions for Malibran. However, the revised score didn't arrive on time, so the performances were canceled, and the contract was dropped. In March, Bellini did nothing but attend the final performance of Puritani. On April 1, he wrote a long letter to Ferlito, describing his life in Paris and his old worries about Donizetti and Rossini. He mentioned his future plans to get a contract with the French Grand Opéra and make Paris his home. He also talked about possibly marrying a young woman who wasn't rich but had wealthy relatives.

Throughout May, Bellini heard about I puritani's success in London and the failure of a Norma revival there due to poor singing. He was glad that Grisi hadn't performed Norma in Paris. Over the summer, Bellini's mood was described as "dark." Discussions with the Opéra were on hold, and he wrote long letters filled with projects and ideas. These things suggested he was deeply troubled.

Earlier that year, Bellini met the writer Heinrich Heine at a literary gathering. Heine later wrote about Bellini in his unfinished novel Florentine Nights, describing him as "a sigh in dancing pumps."

Bellini's last known letter to Filippo Santocanale was on August 16, followed by one to Florimo on September 2. In the latter, he mentioned being "slightly disturbed by a diarrhea" for three days but felt better.

Final Illness and Death

Bellini clearly did not like Heine's remarks. Madame Joubert, a friend, tried to bring them together by inviting them to dinner. Bellini didn't show up, sending a note that he was too ill. Doctor Luigi Montallegri was sent to Puteaux to check on him. Over a few days, the doctor sent notes reporting on Bellini's condition. On September 20, there was "no appreciable improvement." The next day, a slight improvement was reported. On September 22, the doctor hoped to declare him out of danger the next day. However, a fourth note on September 22 was more pessimistic, stating it was the thirteenth day of illness and Bellini had a "very restless night." On September 23, Montallegri reported a "terrifying convulsion," and Bellini died around 5 pm.

Rossini immediately took charge of the funeral arrangements and Bellini's estate. He ordered a post-mortem examination, as requested by the King.

Rossini formed a committee of Parisian musicians to raise money for a monument to Bellini and to organize a funeral mass on October 2.

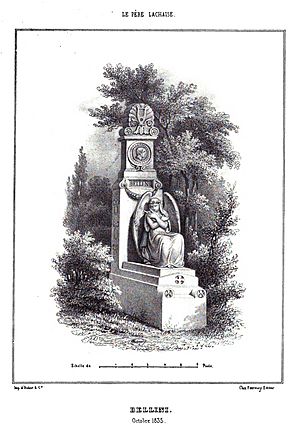

Rossini wrote detailed letters to Santocanale in Palermo about everything he had done. Initially, Bellini was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery as a temporary arrangement. Despite efforts over many years, Bellini's remains were not moved to Catania until 1876. His casket was taken to the cathedral in Catania and reburied. His empty tomb in Père Lachaise Cemetery remains, next to Rossini's, whose bones were also later moved back to Italy.

Many tributes poured in after Bellini's death. One notable tribute was written by Felice Romani and published in Turin on October 1, 1835.

Today, the Museo Belliniano, located in the Palazzo Gravina-Cruyllas in Catania (Bellini's birthplace), preserves his belongings and manuscripts. Bellini was featured on the front of the Banca d'Italia 5,000 lire banknote in the 1980s and 90s, with a scene from Norma on the back.

Bellini, Romanticism, and Melodrama

When planning his opera for Parma in 1829, Bellini was given power to choose the librettist. He rejected the work of Luigi Torrigiani, who complained that Bellini "likes Romanticism and exaggeration. He declares that Classicism is cold and boring." Torrigiani also noted that Bellini liked "unnatural meetings in forests, among graves, tombs and the like."

When writing the libretto for Zaira, Romani explained that he didn't cover Zaira with the "ample cloak of Tragedy" but instead "wrapped [it] in the tight form of Melodrama."

Personal Life and Relationships

Three people were very important in Bellini's life: Francesco Florimo, Maddalena Fumaroli, and Giuditta Turina.

Francesco Florimo

Francesco Florimo was one of Bellini's closest friends. They met as students at the Naples Conservatory and wrote many letters to each other throughout Bellini's life. During the 1820 revolution, Bellini and Florimo joined a secret society called the Carboneria. After Bellini left Naples for Milan, they rarely saw each other. Their last meeting was in Naples in late 1832. Bellini later said that Florimo "was the only friend in whom [I] could find comfort." After Bellini's death, Florimo became responsible for his writings and papers.

Maddalena Fumaroli

Bellini had a relationship with Maddalena Fumaroli early in his career. Her parents did not approve of him because he was a "poor piano player." However, after Bianca e Gernado became a success, Bellini hoped her parents would change their minds. They did, but by then, Bellini's feelings had changed. He was focused on his career and felt he couldn't support her financially. Even Maddalena's own pleas in letters didn't change his mind.

Giuditta Turina

After 1828, Bellini had a five-year relationship with Giuditta Turina, a married woman. Their relationship began in Genoa in April 1828. Bellini's letters to Florimo show he was happy with the relationship because it allowed him to avoid marriage and focus on his work.

However, in May 1833, while Bellini was in London, Giuditta's husband found a letter from Bellini. This led to her husband seeking a legal separation. Bellini didn't want the responsibility of caring for her, as his feelings for her had cooled. He wrote to Florimo from Paris that he was constantly threatened by Giuditta coming to Paris, and he would leave if she did. He stated, "I no longer want to be put in the position of renewing a relationship that made me suffer great troubles." When Turina decided to leave her husband, Bellini left her. He said that with his many commitments, such a relationship would be "fatal" to his career. He avoided long-term romantic commitments and never married.

Giuditta Turina stayed in touch with Florimo throughout her life. After Bellini's death, they corresponded for years, and Florimo even visited her in Milan. She passed away on December 1, 1871.

Complete Works of Bellini

Operas

In 1999, the music publisher Casa Ricordi and the Teatro Massimo Bellini in Catania started a project to publish all of Bellini's works.

| Title | Type of Opera | Acts | Libretto by | First Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Place | ||||

| Adelson e Salvini | opera semiseria (half-serious opera) | 3 acts | Andrea Leone Tottola | 12 (?) February 1825 | Naples, Teatro del Conservatorio di San Sebastiano |

| Bianca e Gernando | melodramma | 2 acts | Domenico Gilardoni | 30 May 1826 | Naples, Teatro San Carlo |

| Il pirata | melodramma | 2 acts | Felice Romani | 27 October 1827 | Milan, Teatro alla Scala |

| Bianca e Fernando (a new version of Bianca e Gernando) |

melodramma | 2 acts | Felice Romani | 7 April 1828 | Genoa, Teatro Carlo Felice |

| La straniera | melodramma | 2 acts | Felice Romani | 14 February 1829 | Milan, Teatro alla Scala |

| Zaira | tragedia lirica (lyric tragedy) | 2 acts | Felice Romani | 16 May 1829 | Parma, Teatro Ducale |

| I Capuleti e i Montecchi | tragedia lirica (lyric tragedy) | 2 acts | Felice Romani | 11 March 1830 | Venice, Teatro La Fenice |

| La sonnambula | opera semiseria (half-serious opera) | 2 acts | Felice Romani | 6 March 1831 | Milan, Teatro Carcano |

| Norma | tragedia lirica (lyric tragedy) | 2 acts | Felice Romani | 26 December 1831 | Milan, Teatro alla Scala |

| Beatrice di Tenda | tragedia lirica (lyric tragedy) | 2 acts | Felice Romani | 16 March 1833 | Venice, Teatro La Fenice |

| I puritani | melodramma serio (serious melodrama) | 3 acts | Carlo Pepoli | 24 January 1835 | Paris, Théâtre-Italien |

Songs

The following fifteen songs were published together in a collection called Composizioni da Camera in 1935, 100 years after Bellini's death.

Six Early Songs

- "La farfalletta" – a little song

- "Quando incise su quel marmo" – scene and aria

- "Sogno d'infanzia" – romance

- "L'abbandono" – romance

- "L'allegro marinaro" – ballad

- "Torna, vezzosa fillide" – romance

Three Little Arias

- "Il fervido Desiderio"

- "Dolente immagine di Fille mia"

- "Vaga luna, che inargenti"

Six Little Arias

- "Malinconia, Ninfa gentile"

- "Vanne, o rosa fortunata"

- "Bella Nice, che d'amore"

- "Almen se non poss'io"

- "Per pietà, bell'idol mio"

- "Ma rendi pur contento"

Other Works

- Eight symphonies, including a Capriccio, ossia Sinfonia per studio (Capriccio or Study Symphony), composed around 1820. Bellini's symphonies are short pieces, like Italian overtures, not long works like those by Beethoven.

- Oboe Concerto in E-flat major

- Seven piano pieces, three of them for four hands (two players at one piano)

- An Organ Sonata in G major

- 40 sacred works, including:

- ("Catania" No. 1) Mass in D major (1818)

- ("Catania" No. 2) Mass in G major (1818)

- Messa di Gloria in A minor for solo singers, choir, and orchestra (1821)

- Mass in E minor (Naples, around 1823)

- Mass in G minor (Naples, around 1823)

- Salve Regina in A major for choir and orchestra (around 1820)

- Salve Regina in F minor for solo voice and piano (around 1820)

See also

In Spanish: Vincenzo Bellini para niños Other important bel canto opera composers:

In Spanish: Vincenzo Bellini para niños Other important bel canto opera composers:

- Gioachino Rossini

- Gaetano Donizetti

- Saverio Mercadante