Gilbert and Sullivan facts for kids

Gilbert and Sullivan refers to the amazing team of writer W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900). They worked together during the Victorian era in England. They created fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896. Some of their most famous works include H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, and The Mikado.

Gilbert wrote the stories and words for these operas, called libretti. He created funny, "topsy-turvy" worlds where silly ideas were taken to their extreme. Sullivan, who was six years younger, wrote the music. His melodies were catchy and could be both funny and touching.

Their operas became very popular all over the world. People still perform them often, especially in English-speaking countries. Gilbert and Sullivan brought new ideas to musical theatre. They influenced how musicals were made throughout the 1900s. Their operas also affected books, movies, TV shows, and even how politicians talk. Many comedians have made fun of or copied their style. The producer Richard D'Oyly Carte helped bring Gilbert and Sullivan together. He built the Savoy Theatre in 1881 just for their operas, which became known as the Savoy Operas. He also started the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, which performed their works for over 100 years.

Contents

How It All Began

Gilbert's Early Life

Gilbert was born in London on November 18, 1836. His father, William, was a naval surgeon who later wrote stories. Gilbert started writing his own stories, poems, and articles in 1861 to earn more money. Many of these early writings, especially his illustrated poems called the Bab Ballads, later inspired his plays and operas.

In his Bab Ballads and early plays, Gilbert developed a special "topsy-turvy" style. He would start with a silly idea and then show what would logically happen, no matter how absurd. For example, a judge might marry the person suing him! This style mixed the strange with the real in a very clever way.

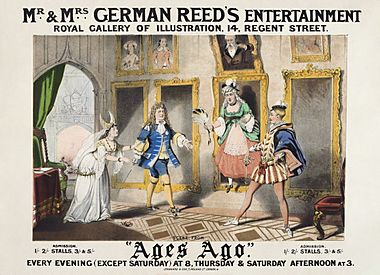

Gilbert also had new ideas about directing plays. He wanted actors to be realistic and not just joke with the audience. He helped make theatre more respected in Britain. He wrote six short, family-friendly comic operas for Thomas German Reed. At a rehearsal for one of these, Ages Ago, in 1870, Gilbert met the young composer Arthur Sullivan. Before they worked together, Gilbert continued writing funny poems and plays.

Sullivan's Early Life

Sullivan was born in London on May 13, 1842. His father was a military bandmaster. By age eight, Arthur could play all the instruments in the band! He started writing songs and hymns in school. In 1856, he won a special scholarship. He studied music at the Royal Academy of Music and in Leipzig, Germany.

His first big success was music for Shakespeare's play The Tempest in 1862. This made him known as England's most promising young composer. He wrote symphonies, concertos, and overtures. However, these serious works didn't earn him enough money. So, he also worked as a church organist and wrote many popular songs.

Sullivan's first comic opera was Cox and Box in 1866. He wrote it with F. C. Burnand for a private gathering. It was very successful and is still performed today. Gilbert, who was a critic at the time, even said Sullivan's music was "too high a class" for the silly story.

Their Famous Operas

First Works Together

Thespis: Their First Try

In 1871, producer John Hollingshead asked Gilbert and Sullivan to create a Christmas show called Thespis. It was a funny play where old Greek gods were replaced by 19th-century actors. The show made fun of politics and serious operas.

Thespis opened on Boxing Day and ran for 63 performances. It did better than many other shows that holiday season. However, no one knew then that this was the start of a great partnership. The show was put together quickly, and its music was never fully published. Most of it is now lost.

For the next three years, Gilbert and Sullivan worked separately. Both became more famous in their own fields. The number of people going to the theatre was also growing. More people had pianos at home and enjoyed music.

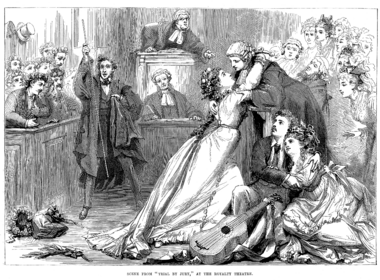

Trial by Jury: A Big Hit

In 1874, Gilbert wrote a short opera story for another producer, but the project stopped. Soon after, Richard D'Oyly Carte needed a short opera for his theatre. He knew about Gilbert's story and asked Sullivan to write music for it. Gilbert read the story to Sullivan in February 1875, and Sullivan loved it! Trial by Jury was created and staged in just a few weeks.

This opera is a funny take on law and lawyers. It's about a man who broke his promise to marry a woman. The man says he's a "very bad lot," so the damages should be small. The woman says she loves him and wants "substantial damages." In the end, the judge solves the case by marrying the woman himself! The show was a huge success.

Sullivan's brother, Fred, played the funny judge. He helped create the "patter" (comic) baritone roles that became famous in their later operas. These characters were often the main funny person in the show and sang fast, witty songs.

After Trial by Jury was a hit, everyone wanted Gilbert and Sullivan to write more operas together. Carte tried to get them to work on another show, but it didn't happen right away.

Their Early Triumphs

The Sorcerer: A New Beginning

Carte wanted to create a new kind of English light opera. He wanted it to be better than the rude shows and poorly translated French operas popular at the time. He formed a company and asked Gilbert and Sullivan to write a full-length comic opera.

Gilbert found an idea in one of his own short stories. It was about a love potion that caused problems in a small village. The main character was a businessman who was also a sorcerer. Gilbert and Sullivan worked very hard to make The Sorcerer (1877) a perfect show. It was much more polished than Thespis. While critics liked it, it wasn't as big a hit as Trial by Jury. Still, it ran for over six months, which was good enough for Carte to ask for another opera.

H.M.S. Pinafore: An International Sensation

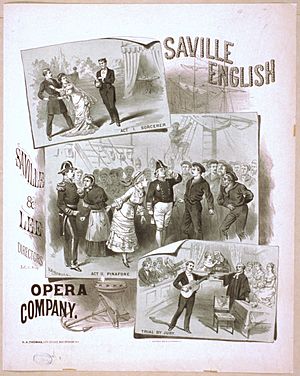

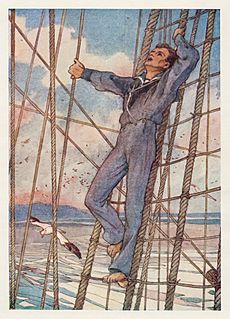

Gilbert and Sullivan had their first international hit with H.M.S. Pinafore (1878). This opera made fun of people getting important jobs without being qualified. It also gently teased the Royal Navy and how much English people cared about social class. Like many of their operas, a surprising twist at the end changes everything.

Gilbert was very involved in the show's look and how the actors performed. He wanted acting to be realistic. He made sure actors knew their lines perfectly and followed his directions. Sullivan made sure the music was just right. This made their shows very sharp and polished.

H.M.S. Pinafore ran for 571 performances in London, which was a very long time back then. Many unauthorized versions of Pinafore appeared in America. During the show's run, Richard D'Oyly Carte had problems with his old business partners. These partners even tried to steal the scenery during a performance! This event led Carte, Gilbert, and Sullivan to form the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company. This company then produced all their future operas.

The story of H.M.S. Pinafore used common character types, like the brave hero, his love interest, and a funny older woman. Gilbert and Sullivan added the funny "patter-singing" character. With H.M.S. Pinafore's success, the D'Oyly Carte company system became set. They would use the same types of characters in each opera. Gilbert and Sullivan chose the actors themselves and wrote for the whole group, not just one big star.

Actors like George Grossmith (the main comedian) and Jessie Bond (a mezzo-soprano) became stars by staying with the company for many years. The funny patter character who was a sorcerer in one show might become a navy ruler in the next, and then a major-general!

The Pirates of Penzance: More Fun and Satire

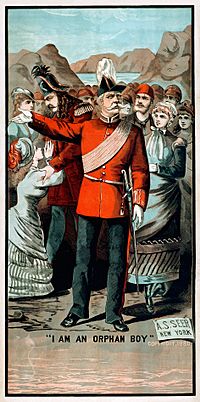

The Pirates of Penzance (New Year's Eve, 1879) also made fun of serious operas, ideas of duty, family rules, and being "respectable." The story also brought back the idea of unqualified people in charge, like the "modern Major-General" who knows everything except about the military. The Major-General and his many daughters escape from the kind-hearted pirates by falsely claiming he is an orphan. But when the pirates find out he lied, they capture him again. Then, it's revealed that the pirates are all noblemen! So, the Major-General tells them to go back to their important jobs and marry his beautiful daughters.

This opera first opened in New York, not London. This was an attempt to protect their rights in America, but it didn't fully work. Still, Pirates was a big hit in both New York and London. It became one of their most performed and copied works.

The Savoy Theatre Opens

Patience: Teasing Art and Fashion

Patience (1881) made fun of the "aesthetic movement," which was a popular art and fashion trend. It combined ideas from famous poets and artists like Oscar Wilde. The opera also teased male vanity and military pride. The story is about two rival poets who attract all the young ladies in the village. But both poets love Patience, a milkmaid.

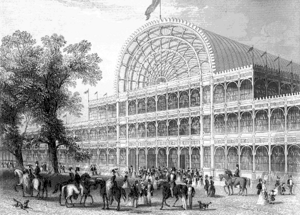

While Patience was running, Carte built the new, modern Savoy Theatre. It was the first public building in the world to be lit entirely by electricity! Patience moved to the Savoy and ran for 578 performances, even longer than H.M.S. Pinafore.

Iolanthe: Fairies and Lords

Iolanthe (1882) was the first opera to open at the new Savoy Theatre. The electric lights allowed for cool special effects, like sparkling magic wands for the fairy chorus. The opera made fun of English law and the House of Lords. It also explored the "war between the sexes." Critics thought Sullivan's music for Iolanthe was a big step forward.

Iolanthe is one of Gilbert's stories where men and "mortal love" cause problems in a peaceful world of women. Gilbert had written similar "fairy comedies" before. These plays often showed characters revealing their true selves under the influence of magic.

In 1882, Gilbert had a telephone installed at his home and at the Savoy Theatre. This allowed him to check on performances from home. Sullivan also had one. In 1883, at Sullivan's birthday party, guests including the Prince of Wales (who later became King Edward VII) listened to parts of Iolanthe live from the Savoy! This was probably the first live "broadcast" of an opera.

During Iolanthe's run in 1883, Queen Victoria made Sullivan a knight. This honor was for his serious music, even though his operas with Gilbert made him most famous. Many people thought this meant he should stop writing comic operas. But Sullivan had signed a five-year agreement with Gilbert and Carte to write more comic operas.

Princess Ida: Women's Education

Princess Ida (1884) made fun of women's education and male chauvinism (the idea that men are better than women). It continued the theme from Iolanthe about the battle between the sexes. The opera is based on a poem by Tennyson. Gilbert had written a play based on the same poem in 1870, and he used much of that play's dialogue in Princess Ida. This opera is the only one by Gilbert and Sullivan where all the dialogue is in blank verse (poetry without rhyme). It's also their only three-act opera.

Princess Ida was not as successful as their previous operas. A very hot summer in London didn't help ticket sales. It ran for 246 performances, which was short for them. Sullivan felt he couldn't write another opera like the ones they had already done. So, when Ida closed, Carte brought back The Sorcerer.

The Famous Mikado

The Mikado: A Japanese Twist

Their most successful opera was The Mikado (1885). It made fun of English government rules, but it was set in Japan. Gilbert first suggested a story about a magic lozenge (a type of candy) that would change characters. Sullivan didn't like this idea, saying it wasn't realistic. After some disagreement, Gilbert agreed to write a story without magic.

The story is about Ko-Ko, a "cheap tailor" who becomes the Lord High Executioner of Titipu. He loves Yum-Yum, but she loves a musician. This musician is actually the son of the Emperor of Japan (the Mikado) and is in disguise. The Mikado has ordered that executions must happen in Titipu. When the Mikado plans to visit, Ko-Ko worries he'll be in trouble for not executing anyone. He comes up with a plan to trick the Mikado, but it goes wrong. In the end, Ko-Ko has to convince an older woman named Katisha to marry him to save everyone's lives.

At the time, Japanese art and styles were very popular in England. A Japanese village exhibition even opened in London. This made it a perfect time for an opera set in Japan. Gilbert said the Japanese setting allowed for colorful costumes and scenery. He also said the Mikado in the opera was an imaginary ruler from a long time ago, so it wasn't making fun of the real Japanese government.

The Mikado became their longest-running hit, with 672 performances at the Savoy Theatre. It is still the most performed Savoy Opera. It has been translated into many languages and is one of the most played musical theatre pieces ever.

Ruddigore: Ghosts and Melodrama

Ruddigore (1887) was a funny take on Victorian melodramas (plays with over-the-top emotions). It was less successful than their earlier works, running for 288 performances. The original title, Ruddygore, and some parts of the story, like ghosts coming back to life, got some negative comments. Gilbert and Sullivan changed the spelling and made some other edits. Still, the show made money, and some critics liked it.

Some ideas in Ruddigore came from Gilbert's earlier opera, Ages Ago, like the story of a wicked ancestor and ghosts stepping out of portraits. When Ruddigore closed, there was no new opera ready. Gilbert again suggested his "lozenge" plot, but Sullivan still didn't want to do it. While they worked things out, Carte brought back popular old operas like H.M.S. Pinafore and The Mikado.

The Yeomen of the Guard: A Serious Turn

The Yeomen of the Guard (1888) was their only opera with a serious ending. It's about a jester and a singing girl who get caught up in a dangerous plot at the Tower of London in the 1500s. The language sounds old-fashioned, but it's not a satire of British institutions. Gilbert used ideas from his 1875 play, Broken Hearts. Critics praised Gilbert's story for trying something new.

This opera gave Sullivan a chance to write his most ambitious music for the theatre. Critics, who had recently praised his serious music, thought the music for Yeomen was his best. It was a hit, running for over a year. However, Sullivan told Gilbert that he no longer enjoyed writing comic operas. He felt he had to simplify his music so Gilbert's words could be heard.

Sullivan insisted their next opera should be a grand opera (a very serious opera). Gilbert didn't think he could write a grand opera story. They agreed to write a light opera for the Savoy and, at the same time, Sullivan would write a grand opera (Ivanhoe) for a new theatre Carte was building.

The Gondoliers: Kings and Equality

The Gondoliers (1889) takes place in Venice and a fictional kingdom. It's about two gondoliers who try to make the monarchy (the king's rule) more equal. Gilbert brought back themes from his earlier works, like making fun of class differences. Critics loved it.

The opera ran for a very long time, almost as long as H.M.S. Pinafore and The Mikado. In 1891, Queen Victoria and the royal family watched a special performance of The Gondoliers at Windsor Castle. This was the first Gilbert and Sullivan opera to receive such an honor. The Gondoliers was their last big success together.

The "Carpet Quarrel"

Gilbert and Sullivan usually got along well, but sometimes their working relationship was difficult. This was especially true during their later operas. Gilbert was often direct and easily upset, while Sullivan avoided conflict. Gilbert's funny, "topsy-turvy" stories sometimes clashed with Sullivan's desire for more realistic and emotional music. Also, Gilbert often made fun of the wealthy and powerful, whom Sullivan wanted as friends.

They disagreed several times about what their operas should be about. After Princess Ida and Ruddigore, which were less successful, Sullivan wanted to stop working with Gilbert. He felt Gilbert's plots were too similar and not artistic enough. When they had these disagreements, Carte kept the Savoy Theatre open by showing their older, popular works. Each time, after a few months, Gilbert would write a story that met Sullivan's wishes, and they would continue working together.

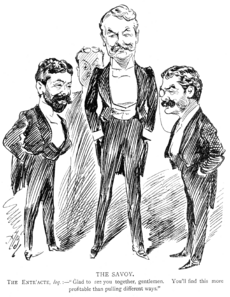

In April 1890, while The Gondoliers was playing, Gilbert argued with Carte about the production costs. Gilbert was upset that Carte had charged the cost of a new carpet for the Savoy Theatre lobby to their partnership. Gilbert thought Carte alone should pay for maintenance. Gilbert confronted Carte, who refused to change the accounts. Gilbert was very angry and sued Carte.

Sullivan supported Carte in the lawsuit. He made a statement that was later found to be incorrect. When Gilbert found out, he asked Sullivan to take back his statement, but Sullivan refused. Gilbert felt this was a serious moral issue. Sullivan felt Gilbert was questioning his honesty. Also, Sullivan wanted to stay on good terms with Carte because Carte was building a new theatre for Sullivan's serious opera, Ivanhoe. After The Gondoliers closed in 1891, Gilbert stopped allowing his operas to be performed at the Savoy. He said he would not write any more operas for them.

Gilbert eventually won the lawsuit. However, his actions had hurt his partners. But their partnership had been so successful that Carte and his wife wanted to bring them back together. In late 1891, after many tries, their music publisher, Tom Chappell, helped them make up. This led to two more operas by Gilbert and Sullivan.

Their Last Works

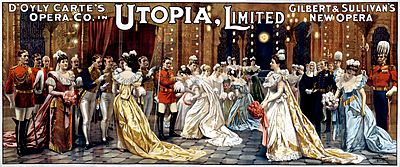

Utopia, Limited (1893), their second-to-last opera, was only a small success. Their very last opera, The Grand Duke (1896), was not successful at all. These two operas were not performed regularly until the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company made recordings of them in the 1970s. Gilbert offered Sullivan another story, His Excellency (1894). But Gilbert insisted on casting his favorite actress, Nancy McIntosh, which made Sullivan refuse. So, another composer wrote the music for His Excellency.

The Savoy Theatre continued to show revivals of Gilbert and Sullivan operas. After The Grand Duke, the partners decided not to work together again. They had one last misunderstanding in 1898. Gilbert went to the premiere of Sullivan's opera The Beauty Stone, thinking Sullivan had saved seats for him. But he was told Sullivan didn't want him there. Sullivan later said this wasn't true. The last time they met was at the Savoy Theatre on November 17, 1898, for a celebration of The Sorcerer's 21st anniversary. They did not speak to each other.

Sullivan, who was very sick, died in 1900. Gilbert wrote that any memory of their disagreements had "completely bridged over." He said, "Sullivan... was as modest and as unassuming as a beginner should be... I remember all that he has done for me in allowing his genius to shed some of its lustre upon my humble name."

Richard D'Oyly Carte died in 1901. His wife, Helen, then managed the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company. Gilbert mostly retired but continued to direct revivals of the operas. Between 1906 and 1909, he helped Mrs. Carte stage two popular seasons of the operas at the Savoy Theatre. Gilbert was made a knight during the first of these seasons. After Sullivan's death, Gilbert wrote only one more comic opera, Fallen Fairies (1909), which was not a success.

Their Lasting Impact

Gilbert died in 1911. Richard D'Oyly Carte's son, Rupert D'Oyly Carte, took over the opera company when his step-mother died in 1913. His daughter, Bridget, inherited the company in 1948. The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company performed Gilbert and Sullivan operas almost all year round until it closed in 1982. Over the 1900s, the company gave more than 35,000 performances. The Savoy operas were also performed a lot in North America, Australia, Germany, Russia, and other parts of the world.

In 1922, Sir Henry Wood explained why their operas were so successful. He said Sullivan was unmatched for his bright, funny, and charming music. His music perfectly fit Gilbert's words. He added that Gilbert's words were much more than just words for Sullivan's music, and Sullivan's music was more than just an accompaniment. They were "two masters who are playing a concerto." Their rare blend of words and music makes these operas truly special.

G. K. Chesterton also praised their combination. He said Gilbert's humor was so smart that it might not have been understood without Sullivan's music. The music gave "wings to his words" and perfectly expressed their light and witty style. In 1957, The Times newspaper said the operas stayed popular because they were never really "in fashion" in the first place. They created an artificial world that has not gone out of style. Gilbert's clever plots and language, with its formal but mocking tone, are perfectly matched by Sullivan's graceful and witty tunes. Together, they are "endlessly and incomparably delightful."

Because the operas were so successful, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company could allow other professional and amateur groups to perform them. For almost 100 years, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company influenced how the operas were performed worldwide. Gilbert, Sullivan, and Carte also had a big impact on amateur theatre. Before them, professional actors looked down on amateur groups. But after Gilbert and Sullivan companies formed in the 1880s, professionals realized that amateur groups helped music and drama. Many professional actors even started in amateur Gilbert and Sullivan groups.

After the rights to the operas expired in Britain in 1961, many other professional companies started performing and recording them. Today, many professional and amateur groups, schools, and universities continue to produce these works. The most popular Gilbert and Sullivan operas are still performed by major opera companies. Since 1994, the International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival has been held every August in England. It features many performances and related events. A critic in 2009 wrote that the charm, silliness, and gentle humor of G&S seem to be "immune to fashion."

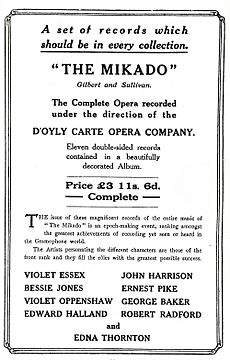

Recordings and Broadcasts

The first commercial recordings of songs from the Savoy operas began in 1898. In 1917, the Gramophone Company (HMV) released the first full recording of a Gilbert and Sullivan opera, The Mikado. They later recorded eight more. The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company continued to make popular recordings until 1979, which helped keep the operas well-known for decades. Many of these recordings are now available on CD.

After the rights expired, many companies worldwide released audio and video recordings of the operas. In the 1960s and 1980s, BBC Radio broadcast complete cycles of the thirteen existing Gilbert and Sullivan operas. Since 1994, the International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival has released many recordings of its productions.

Cultural Influence

For almost 150 years, Gilbert and Sullivan have greatly influenced popular culture in English-speaking countries. Many phrases from their operas have become common sayings, even if Gilbert didn't invent them. Examples include "short, sharp shock", "What never? Well, hardly ever!", and "let the punishment fit the crime". Their operas have influenced politics, books, movies, and TV. Humorists often copy or make fun of their style. Their works have even been quoted in legal rulings.

American and British musical theatre owes a lot to Gilbert and Sullivan. Early musical theatre writers and composers admired and copied them. Later artists like Jerome Kern and Andrew Lloyd Webber were also influenced. Gilbert's lyrics were a model for many 20th-century lyricists. Noël Coward wrote that he grew up hearing Gilbert and Sullivan songs everywhere.

Professor Carolyn Williams noted that the influence of Gilbert and Sullivan goes beyond musical theatre to comedy in general. Their wit and irony, and how they made fun of politics, are still seen in popular culture today. Gilbert and Sullivan expert Ian Bradley agrees. He says their influence can be seen in British comedy that focuses on wit and irony, like Yes Minister, which gently teases authority.

Gilbert and Sullivan's works are often copied and parodied. Famous examples include Tom Lehrer's The Elements and songs by Allan Sherman. Comedians like Anna Russell have used their songs in their acts. Songs from Gilbert and Sullivan are often used in advertisements. Their operas are also often mentioned in books, movies, and TV shows. There are also movies about Gilbert and Sullivan, like Mike Leigh's Topsy-Turvy (1999).

Because Gilbert often focused on politics, politicians and observers have found inspiration in his works. Chief Justice of the United States William Rehnquist added gold stripes to his robes after seeing them on the Lord Chancellor in a production of Iolanthe. British politicians have even given speeches that sound like Gilbert and Sullivan songs.

Their Collaborations

Main Operas and Original London Performances

- Thespis; or, The Gods Grown Old (1871) 63 performances

- Trial by Jury (1875) 131 performances

- The Sorcerer (1877) 178 performances

- H.M.S. Pinafore; or, The Lass That Loved a Sailor (1878) 571 performances

- The Pirates of Penzance; or, The Slave of Duty (1879) 363 performances

- The Martyr of Antioch (a cantata, a type of musical story) (1880) (Gilbert helped with the words)

- Patience; or Bunthorne's Bride (1881) 578 performances

- Iolanthe; or, The Peer and the Peri (1882) 398 performances

- Princess Ida; or, Castle Adamant (1884) 246 performances

- The Mikado; or, The Town of Titipu (1885) 672 performances

- Ruddigore; or, The Witch's Curse (1887) 288 performances

- The Yeomen of the Guard; or, The Merryman and his Maid (1888) 423 performances

- The Gondoliers; or, The King of Barataria (1889) 554 performances

- Utopia, Limited; or, The Flowers of Progress (1893) 245 performances

- The Grand Duke; or, The Statutory Duel (1896) 123 performances

Overtures

The overtures (the music played at the beginning of an opera) from Gilbert and Sullivan operas are still popular. Most of them are a mix of tunes from the opera. Sullivan wrote some of them himself, like for Thespis, Iolanthe, Princess Ida, The Yeomen of the Guard, The Gondoliers, and The Grand Duke. Others were written by his assistants, but always based on Sullivan's ideas.

In the 1920s, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company asked its music director, Geoffrey Toye, to write new overtures for Ruddigore and The Pirates of Penzance. Toye's Ruddigore overture is often heard today.

Other Versions

Translations

Gilbert and Sullivan operas have been translated into many languages. These include Yiddish, Hebrew, Portuguese, Swedish, Dutch, Danish, Estonian, Hungarian, Russian, Japanese, French, Italian, Spanish, and others. There are many German versions, including the popular Der Mikado.

Ballets

- Pineapple Poll: A ballet created in 1951. It's based on Gilbert's 1870 poem "The Bumboat Woman's Story," which also inspired H.M.S. Pinafore. The music is arranged from Sullivan's themes.

- Pirates of Penzance - The Ballet!: Created for the Queensland Ballet in 1991.

Adaptations

Gilbert himself adapted the stories of H.M.S. Pinafore and The Mikado into children's books. Many other children's books have since retold their stories. The most popular Gilbert and Sullivan songs were also adapted into dance pieces in the 1800s.

Many musical theatre and film versions of the operas have been made, including:

- The Swing Mikado (1938; an all-black cast)

- The Hot Mikado (1939)

- The Cool Mikado (1962 film)

- The Black Mikado (1975)

- Dick Deadeye, or Duty Done (1975 animated film)

- The Pirate Movie (1982 film)

- The Ratepayers' Iolanthe (1984; a musical that won an award)

- The Metropolitan Mikado (a political satire from 1985)

- Di Yam Gazlonim (1986; a Yiddish version of Pirates)

- Gondoliers: A Mafia-themed version of the opera (2001)

- Parson's Pirates (2002)

- The Ghosts of Ruddigore (2003)

- Pinafore Swing (2004; another modern adaptation)

See also

In Spanish: Gilbert y Sullivan para niños

In Spanish: Gilbert y Sullivan para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |