Volunteer Force facts for kids

The Volunteer Force was like a citizen army made up of part-time groups of rifle shooters, artillery (big guns), and engineers. It started as a popular movement across the British Empire in 1859.

At first, these volunteer groups were very independent. But over time, they became more connected with the British Army, especially after some big changes in 1881. Eventually, in 1908, they became part of the Territorial Force. Many of the army units you see today, like the Army Reserves for foot soldiers, artillery, engineers, and signals, can trace their history back to these early Volunteer Force units.

Contents

Why Britain Needed Volunteers

Before the Crimean War (a big war in the 1850s), the British military on land was split into different parts. There were the Regular Forces (professional soldiers like the British Army) and the Reserve Forces (part-time groups).

After the Crimean War, it became very clear that Britain didn't have enough soldiers at home. Many regular soldiers were stationed all over the British Empire to guard its territories. This meant there weren't enough troops ready to fight if a new conflict started, or even to defend Britain itself. During the Crimean War, Britain even had to send part-time soldiers (called militia and Yeomanry) to help the regular army.

Things got even more tense with France in 1858. There was an attempt to assassinate the French Emperor, Napoleon III, and the bombs used were made in England. This made people in Britain worry that France might invade. Britain's defenses felt very weak, and a war between France and Austria in 1859 made these fears even stronger.

Starting the Volunteer Force

To deal with these worries, on May 12, 1859, the government officially allowed volunteer groups to form. The Secretary of State for War, Jonathan Peel, sent a letter to leaders in counties across England, Wales, and Scotland. This letter gave permission to create volunteer rifle groups and artillery groups in towns along the coast.

These groups were set up using an old law from 1804, which had been used during the Napoleonic Wars to form local defense forces. Many communities already had rifle clubs for fun, which helped these new volunteer units get started.

Here are some of the rules for these new volunteer groups:

- A group could only be formed if the local county leader (called a lord-lieutenant) approved it.

- Officers in the group got their positions from the lord-lieutenant.

- Volunteers had to promise loyalty to the Queen.

- The force could be called into action if there was an actual invasion, if an enemy appeared on the coast, or if a rebellion happened during these times.

- When called up, volunteers followed military law and received regular army pay.

- Volunteers couldn't quit during active service. At other times, they had to give two weeks' notice.

- To be considered "effective," a volunteer had to attend a certain number of drills and exercises.

- Volunteers usually paid for their own weapons and uniforms. However, the War Office made sure all firearms were the same type.

- Volunteers could choose their uniform design, but the lord-lieutenant had to approve it.

Most rifle groups were planned to have about 100 members. Their job was to bother invading enemies from the sides. Artillery groups were meant to operate coastal guns and forts. Some engineer groups also formed to help protect ports, often by placing underwater mines. Even stretcher-bearers joined, and they later formed volunteer medical teams.

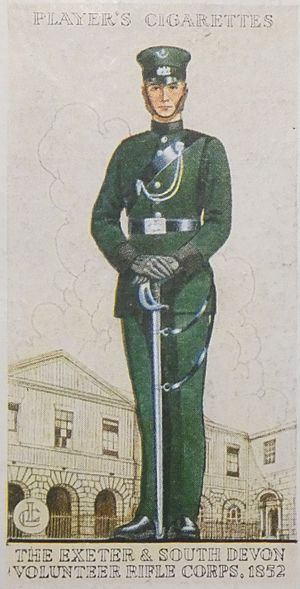

Two volunteer units that had already been accepted by Queen Victoria in the early 1850s became the most important rifle groups in the new force. These were the Exeter and South Devon Volunteers (formed in 1852) and the Victoria Rifles.

At first, there was a bit of a class difference. Middle-class people saw rifle units as different from the regular army, where officers were from rich families and other soldiers were working-class. Many volunteer units chose green or grey uniforms, unlike the red coats of the regular army. This also suited the army, as they didn't want amateur volunteers wearing their official red. The rule that volunteers had to buy their own rifles and uniforms meant that poorer people often couldn't join.

Unlike regular army units, volunteer units often had special flags (called colours) made by women in the community. However, these were not officially allowed by the army.

Making the Force Stronger

Having many small, independent groups was hard to manage. By 1861, most had been combined into larger units, usually the size of a battalion. This happened either by making an existing group bigger (in cities) or by grouping smaller groups together (in rural areas). Official training guides and rules for volunteers were published in 1859 and 1861.

Cadet Corps for Young People

Starting in 1860, Cadet Corps were also formed for school-aged boys. These were the early versions of today's Army Cadet Force and Combined Cadet Force. Like the adult volunteers, the boys received weapons from the War Office, but they had to pay a fee. Cadet Corps were usually linked to private schools and often marched in public.

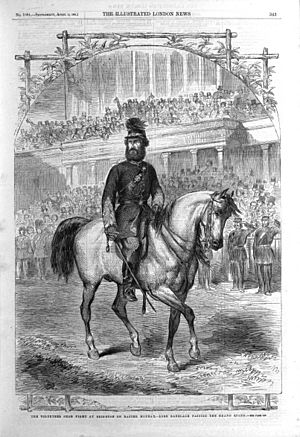

Official Review of 1862

In 1862, a special committee looked into the Volunteer Force. They wanted to know how well it was doing and if it would continue to be strong.

The report found that by April 1, 1862, the Volunteer Force had 162,681 members. This included:

- 662 light horse (cavalry)

- 24,363 artillery (big guns)

- 2,904 engineers

- 656 mounted rifles

- 134,096 rifle volunteers

The committee made some important suggestions about money and training:

- Setting up the volunteer groups had mostly been paid for by public donations. But uniforms and equipment were wearing out, and volunteers would have to pay for replacements, which might make many leave.

- To fix this, the committee suggested the government give money to each volunteer who met certain training standards.

- Groups that received money could spend it on their headquarters, training areas, transport, and maintaining their weapons and uniforms.

- The committee also found that many drill instructors were not very good. They suggested setting up a school for instructors and having volunteers train with regular army troops whenever possible.

The Volunteer Act of 1863

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An act to consolidate and amend the Acts relating to the Volunteer Force in Great Britain. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 26 & 27 Vict. c. 65 |

| Territorial extent |

|

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 21 July 1863 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

To put the committee's ideas into action, the Volunteer Act 1863 was passed. This new law replaced the older one from 1804.

The Act made it legal for the Queen to accept volunteer groups. Existing groups continued under the new law. It also allowed for a permanent staff of officers and instructors for each group. Groups could be combined into larger "administrative regiments," but the individual groups still existed.

The rules for calling out the force changed slightly. They would now be called out "in the case of actual or feared invasion of any part of the United Kingdom." If called up, volunteers and their families would receive pay and support. If a volunteer was injured during service, they would receive a pension.

The Act also set rules for discipline, how groups managed their property, and how they could get land for shooting ranges.

Joining the Regular Army

In 1872, the government took control of the volunteers away from the county leaders and put it under the Secretary of State for War. This meant volunteer units became more and more connected with the Regular Army.

A big change happened in 1881, called the Childers Reforms. Rifle volunteer groups were officially named "volunteer battalions" of the new "county" infantry regiments. These regiments also included regular army and militia battalions from a specific area. Over the next few years, many volunteer groups adopted the "volunteer battalion" name and the uniform of their parent regiment. However, some groups kept their original names and unique uniforms until 1908.

Artillery volunteers also became reserve units of the Royal Artillery, and engineer volunteers became part of the Royal Engineers.

Fighting in the Boer War

The volunteers finally got to fight in a real war during the Second Boer War (1899-1902) in South Africa. The war lasted a long time, so Britain needed more soldiers. Volunteer Battalions formed special companies that joined the regular battalions of their county regiments. After the war, volunteer units that sent soldiers to the campaign were given the special honor "South Africa 1900–02."

The Territorial Force is Born

By 1907, the Volunteer Force had become super important for Britain's defense. It also helped the Regular Army send its own soldiers to other parts of the world. So, in 1907, the government passed a law that combined the Volunteer Force with another part-time force called the Yeomanry. Together, they formed the Territorial Force in 1908. The government would now pay for the entire Territorial Force.

Most of the volunteer units lost their unique names and became numbered battalions of the local army regiment, though they often kept special badges or uniform details.

The new law didn't apply to the Isle of Man. So, the 7th (Isle of Man) Volunteer Battalion was the only remaining Volunteer Force unit until it was disbanded in 1922.

How Many Volunteers?

Here's a look at how many people were in the Volunteer Force over the years:

| Year | Planned Size | Actual Members | Classed as Efficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1861 | 211,961 | 161,239 | 140,100 |

| 1870 | 244,966 | 193,893 | 170,671 |

| 1880 | 243,546 | 206,537 | 196,938 |

| 1885 | 250,967 | 224,012 | 218,207 |

| 1890 | 260,310 | 212,048 | 212,293 |

| 1895 | 260,968 | 231,704 | 224,962 |

| 1899 | 263,416 | 229,854 | 223,921 |

| 1900 | 339,511 | 277,628 | 270,369 |

| 1901 | 342,003 | 288,476 | 281,062 |

| 1902 | 345,547 | 268,550 | 256,451 |

| 1903 | 346,171 | 253,281 | 242,104 |

| 1904 | 343,246 | 253,909 | 244,537 |

| 1905 | 341,283 | 249,611 | 241,549 |

| 1906 | 338,452 | 255,854 | 246,654 |

| 1907 | 335,849 | 252,791 | 244,212 |

See also

- Category:Units and formations of the Volunteer Force (Great Britain)

- Category:Rifle Volunteer Corps of the British Army

- Category:Artillery Volunteer Corps of the British Army

- Category:Engineer Volunteer Corps of the British Army

- Category:Mounted Rifle Volunteers of the British Army

- Category:Volunteer Infantry Brigades of the British Army

- Category:Volunteer Force officers

- British Volunteer Corps – 1794–1803

- 1st Middlesex Volunteers

- Army Reserve (United Kingdom)

- Militia (United Kingdom)

- Volunteer Training Corps (World War I)

- Home Service Force

- Honourable Artillery Company

- Post Office Rifles

- 1st Nottinghamshire (Robin Hood) Volunteer Rifle Corps (VRC)

- Artists' Rifles

- The Liverpool Scottish

- Halifax Volunteer Battalion, Nova Scotia

- Victoria Rifles (Nova Scotia)

- The Royal Hong Kong Regiment (The Volunteers)

- Cambridgeshire Regiment

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |