Nathan Bedford Forrest facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nathan Bedford Forrest

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Birth name | Nathan Bedford Forrest |

| Nickname(s) | "Old Bed" "Wizard of the Saddle" |

| Born | July 13, 1821 Chapel Hill, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | October 29, 1877 (aged 56) Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Buried |

Columbia, Tennessee, U.S.

|

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Unit |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| Relations |

|

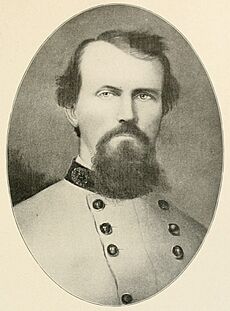

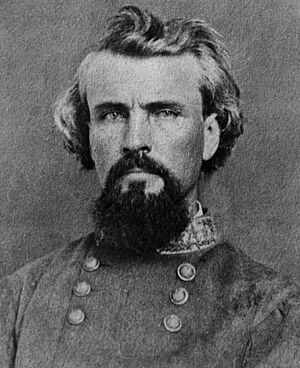

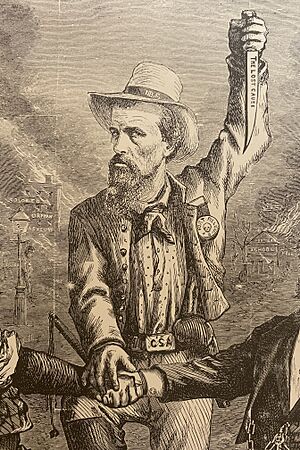

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821 – October 29, 1877) was a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He was also the first leader, known as the Grand Wizard, of the Ku Klux Klan from 1867 to 1869.

Before the war, Forrest became very wealthy. He owned cotton plantations, traded horses and cattle, and was involved in the slave trade. In June 1861, he joined the Confederate Army. He was one of the few soldiers who started as a private and rose to the rank of general without any previous military training.

Forrest was known as an expert cavalry leader. He commanded a large group of cavalry and developed new ways to use mobile forces. This earned him the nickname "The Wizard of the Saddle." He used his cavalry troops like mounted infantry and often used artillery at the front of battles. This helped change how cavalry was used in war.

Forrest is a debated figure in U.S. history. People recognize his skill as a military leader. However, his past as a slave trader and his role in the Fort Pillow incident, where many U.S. Army soldiers (most of them Black) were killed after surrendering, are controversial. His leadership of the Ku Klux Klan after the war is also a major point of controversy.

In June 2021, Forrest and his wife's remains were moved from Health Sciences Park in Memphis, where they had been buried for over 100 years. They were reburied in Columbia, Tennessee. In July 2021, Tennessee officials decided to move Forrest's bust (a statue of his head and shoulders) from the State Capitol to the Tennessee State Museum.

Contents

Early Life and Business Career

Nathan Bedford Forrest was born on July 13, 1821. He came from a poor family living in a cabin near Chapel Hill, Tennessee. This area was then part of Bedford County, Tennessee. He was the first son of Mariam and William Forrest. His father was a blacksmith. Nathan and his twin sister, Fanny, were the oldest of 12 children.

The Forrest family lived in a log house from 1830 to 1833. This house is now preserved as the Nathan Bedford Forrest Boyhood Home. In 1834, his family moved to Salem, Mississippi. When his father died in 1837, 16-year-old Forrest became the main provider for his family.

By 1858, Forrest was elected as a city leader (alderman) in Memphis. He served two terms. In 1859, he bought two large cotton plantations in Mississippi. He also owned part of another plantation in Arkansas. By October 1860, he owned over 3,345 acres in Mississippi. He also bought several cotton plantations in the Mississippi Delta region of West Tennessee.

By the start of the American Civil War in 1861, Forrest was one of the richest men in the Southern United States. He claimed his personal wealth was worth $1.5 million.

Forrest was about 6 feet 2 inches tall and weighed around 180 pounds. People described him as having a "striking and commanding presence." He was usually mild-mannered, but his mood could change quickly if he was angered. He was known as a tireless rider and a skilled swordsman. Even though he did not have much formal education, he could read and write clearly.

Family Life and Connections

Forrest had twelve brothers and sisters. Many of them died young from typhoid fever. His father also died from the effects of the disease when Nathan was 16. In 1845, Forrest married Mary Ann Montgomery. They had two children: William Montgomery Bedford Forrest (born 1846) and a daughter, Fanny (born 1849), who died as a child.

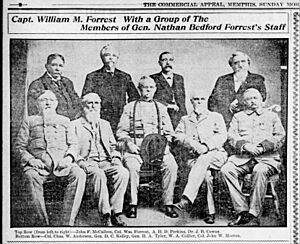

All of Forrest's younger brothers worked with him in the slave trade before the war. Most of them also served as Confederate military officers during the war. Forrest's son, William M. Forrest, served as his assistant. His half-brother, Mat Luxton, was a sergeant and scout in his cavalry.

Forrest's grandson, Nathan Bedford Forrest II, became a leader in the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the Ku Klux Klan. A great-grandson, Nathan Bedford Forrest III, became a brigadier general in the U.S. Army Air Corps. He was killed during a bombing raid in Nazi Germany in 1943.

American Civil War Service

Joining the Cavalry

When the Civil War began, Forrest joined the Confederate States Army on June 14, 1861. He started as a private, along with his youngest brother and 15-year-old son. Forrest noticed that the Confederate Army lacked horses and equipment. He offered to buy these items for a group of Tennessee volunteer soldiers using his own money.

His officers and the Governor of Tennessee were surprised that a wealthy man like Forrest had joined as a private. They made him a lieutenant colonel. He was then allowed to recruit and train a group of Confederate mounted rangers. In October 1861, Forrest was given command of the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry. Even though he had no military training, he quickly showed strong leadership and tactical skills.

Forrest was known for being very strict. He would use physical force to maintain discipline. This led some soldiers and junior officers to avoid serving under him.

Tennessee was divided about joining the Confederacy. Both Confederate and U.S. armies recruited soldiers from the state. Forrest put out advertisements to join his regiment, using the slogan, "Let's have some fun and kill some Yankees!" He also had an elite unit of 40 to 90 men called his "Escort Company."

Early Battles and Promotions

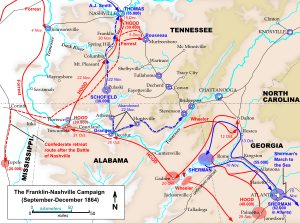

Template:Image flip Forrest earned praise for his actions in the Battle of Sacramento in Kentucky. This was his first battle commanding troops. He led a cavalry charge that defeated a U.S. Army force. He also showed bravery at the Battle of Fort Donelson in February 1862. During a siege by Major General Ulysses S. Grant, Forrest led nearly 4,000 troops to escape across the Cumberland River.

After the Confederates surrendered Fort Donelson, Nashville was about to fall to U.S. forces. Forrest took command of Nashville. He arranged for army supplies and equipment, including cannons, to be moved to other Confederate locations.

A month later, Forrest fought in the Battle of Shiloh (April 6–7, 1862). After the U.S. victory, Forrest commanded the Confederate rear guard. In a smaller fight called Fallen Timbers, he charged alone into a U.S. brigade. He was surrounded and shot through the pelvis. A surgeon removed the bullet a week later without pain medicine.

By early summer, Forrest commanded a new group of inexperienced cavalry. He led them into Middle Tennessee in July. On July 13, 1862, he led them in the First Battle of Murfreesboro. All U.S. units there surrendered to Forrest. The Confederates destroyed many U.S. Army supplies and railroad tracks.

Raids in West Tennessee

On July 21, 1862, Forrest was promoted to brigadier general. He was given command of a Confederate cavalry brigade. In December 1862, his experienced soldiers were moved to another officer. Forrest had to recruit a new group of about 2,000 untrained men, many without weapons.

He was ordered to disrupt the communications of U.S. Army forces under Grant. Forrest argued that sending untrained men behind enemy lines was risky, but he obeyed. In the raids that followed, he was chased by thousands of U.S. soldiers. Forrest avoided attacks by moving quickly and never staying in one place for long. He led his troops on raids into west Tennessee, Kentucky, and north Mississippi.

Forrest returned to his base with more men than he started with. All of them were armed with captured U.S. Army weapons. Grant had to change his plans for the Vicksburg campaign because of Forrest's actions. A newspaper writer who traveled with Grant said Forrest "was the only Confederate cavalryman of whom Grant stood in much dread."

Battles in Alabama and Georgia

The U.S. Army gained control of Tennessee in 1862. Forrest continued to lead small operations, including the Battle of Dover and the Battle of Brentwood. In April 1863, he was sent to northern Alabama and western Georgia. His mission was to defend against an attack by 3,000 U.S. Army cavalrymen led by Colonel Abel Streight. Streight wanted to cut the Confederate railroad south of Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Forrest chased Streight's men for 16 days. Streight's goal changed from destroying the railroad to escaping Forrest. On May 3, Forrest caught up with Streight's unit. Forrest had fewer men but made it seem like he had a larger force. He paraded some of his men around a hilltop repeatedly. This convinced Streight to surrender his tired troops, about 1,500 to 1,700 men.

Chickamauga and Paducah

Forrest fought in the Battle of Chickamauga on September 18–20, 1863. He pursued the retreating U.S. Army and captured many prisoners.

On December 4, 1863, Forrest was promoted to major general. On March 25, 1864, Forrest's cavalry raided Paducah, Kentucky in the Battle of Paducah. Forrest demanded that U.S. Colonel Stephen G. Hicks surrender. Hicks refused. Forrest's troops tried to storm the fort but were pushed back. They made two more attempts, but both failed.

Fort Pillow Incident

Fort Pillow was located near Henning, Tennessee, on the Mississippi River. It was defended by 557 U.S. Army troops, both white and Black soldiers.

On April 12, 1864, Forrest's men attacked and captured Fort Pillow. The U.S. commander was killed, and Major William Bradford took command. Forrest demanded that the fort surrender. He warned that he might not be able to control his men if they had to storm the fort. Bradford refused to surrender, hoping his troops could escape to a U.S. Navy gunboat.

Forrest's men then took over the fort. U.S. Army soldiers retreated to the river bluffs, but the gunboat did not rescue them. What happened next became known as the Fort Pillow Massacre. As the U.S. Army troops surrendered, Forrest's men opened fire. Many Black and white U.S. Army soldiers were killed. Historians note that a much higher percentage of Black soldiers were killed compared to white soldiers. The violence continued through the night.

Because of these events, the U.S. public and press saw Forrest as a war criminal. General Grant later wrote in his memoirs that Forrest's report of the battle "left out the part which shocks humanity to read."

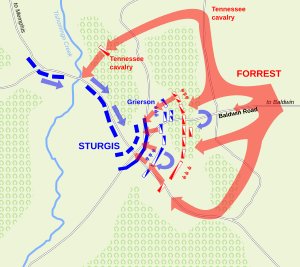

Brices Cross Roads and Tupelo

Forrest's most important victory happened on June 10, 1864. His 3,500 men fought against 8,500 U.S. Army soldiers at the Battle of Brices Crossroads in Mississippi. Forrest's quick movements and smart tactics led to a victory. This allowed him to continue bothering U.S. forces in Tennessee and Mississippi.

Forrest set up an attack position against a pursuing U.S. force. When the U.S. army arrived, they clashed with Forrest's cavalry. The U.S. infantry, tired from the heat, quickly broke and retreated. Forrest ordered a full charge, capturing many artillery pieces, wagons, and weapons. Forrest lost 96 men killed and 396 wounded. The U.S. troops suffered 223 killed, 394 wounded, and 1,623 missing.

One month later, Forrest faced a defeat at the Battle of Tupelo in 1864. U.S. Army forces drove the Confederates from the field. Forrest was wounded in the foot, but his forces were not completely destroyed. He continued to fight U.S. Army efforts in the West for the rest of the war.

Later Raids and Surrender

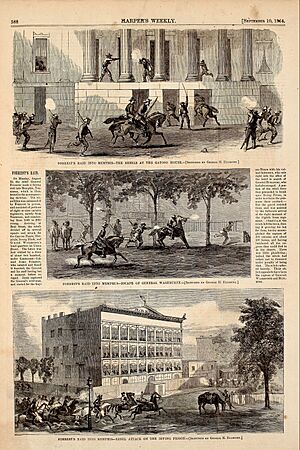

Forrest led other raids that summer and fall. These included a famous raid into downtown Memphis in August 1864 (the Second Battle of Memphis). He also attacked a major U.S. Army supply depot at Johnsonville, Tennessee. On November 4, 1864, during the Battle of Johnsonville, the Confederates shelled the city. They sank three gunboats and nearly thirty other ships, destroying many tons of supplies.

During Hood's Tennessee Campaign, Forrest fought alongside General John Bell Hood. In the Second Battle of Franklin on November 30, Forrest argued with Hood. He wanted permission to cut off the escape route of the U.S. Army. He tried, but it was too late.

After his defeat at Franklin, Hood continued to Nashville. Hood ordered Forrest to attack the Murfreesboro garrison. Forrest succeeded in his objectives. He then fought U.S. forces near Murfreesboro on December 5, 1864. In the Third Battle of Murfreesboro, part of Forrest's command broke and ran.

When Hood's army was destroyed at the Battle of Nashville on December 15–16, Forrest commanded the Confederate rear guard. He led a series of actions that allowed what was left of the army to escape. For this, he was promoted to lieutenant general on March 2, 1865.

In the spring of 1865, Forrest led a defense of Alabama against Wilson's Raid. His opponent, U.S. Army Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson, defeated Forrest at the Battle of Selma on April 2, 1865. A week later, General Robert E. Lee surrendered in Virginia. When Forrest heard this news, he also surrendered. On May 9, 1865, in Gainesville, Forrest gave his farewell address to his men. He urged them to "submit to the powers to be, and to aid in restoring peace and establishing law and order throughout the land."

Forrest's War Record and Promotions

- Enlisted as private July 1861. (White's Company "E", Tennessee Mounted Rifles)

- Commissioned as lieutenant colonel, October 1861 (3rd Tennessee Cavalry)

- Promoted to colonel, February 1862

- Battle of Fort Donelson, February 12–16, 1862

- Wounded at Battle of Shiloh, April 6–8, 1862

- Promoted to brigadier general, July 21, 1862

- First Battle of Murfreesboro, July 1862

- Raids in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Mississippi, December 1862 – January 1863

- Battle of Day's Gap, April 30 – May 2, 1863

- Assigned to command Forrest's Cavalry Corps, May 1863

- Battle of Chickamauga, September 18–20, 1863

- Promoted to major general, December 4, 1863

- Battle of Paducah, March 25, 1864

- Battle of Fort Pillow, April 12, 1864

- Battle of Brices Crossroads, June 10, 1864

- Battle of Tupelo, July 14–15, 1864

- Raids in Tennessee, August–October 1864

- Battle of Spring Hill, November 29, 1864

- Battle of Franklin, November 30, 1864

- Third Battle of Murfreesboro, December 5–7, 1864

- Battle of Nashville, December 15–16, 1864

- Promoted to lieutenant general, February 28, 1865

- Battle of Selma, April 2, 1865

- Farewell address to his troops, May 9, 1865

Life After the War

After the war, the end of slavery meant a big financial loss for Forrest. In 1865, he started a civilian life in Memphis, Tennessee. In 1866, Forrest helped build the Memphis & Little Rock Railroad. The store he built to supply the 1,000 Irish workers became the start of a town. This town was called "Forrest's Town" by residents and became Forrest City, Arkansas in 1870.

Forrest later worked for the Marion & Memphis Railroad and became its president. However, he was not successful in the railroad business. The company went bankrupt under his leadership. This failure nearly ruined him financially.

Forrest spent his last days running an eight-hundred-acre farm on President's Island in the Mississippi River. He and his wife lived in a log cabin there. He used over a hundred prison convicts to grow crops like corn, potatoes, vegetables, and cotton. While this was profitable, his health steadily declined. In May 1877, some described his use of convict labor as similar to slavery. Critics argued it was unfair and took advantage of people.

Death and Burial

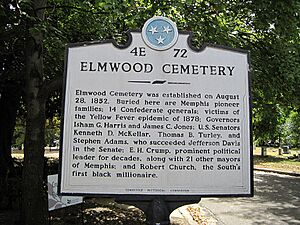

Nathan Bedford Forrest died on October 29, 1877, in Memphis. He reportedly died from complications of diabetes. His funeral procession was over two miles long. An estimated 20,000 people attended, including many Black citizens.

Forrest was buried at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis. In 1904, his and his wife Mary's remains were moved to a Memphis city park. This park was named Forrest Park in his honor, but it is now called Health Sciences Park.

On July 7, 2015, the Memphis City Council voted to remove Forrest's statue from Health Sciences Park. They also voted to return his and his wife's remains to Elmwood Cemetery. However, in October 2017, the Tennessee Historical Commission blocked this decision. Memphis then sold the park land to a non-profit group called Memphis Greenspace. This group was not subject to the state law. They immediately removed the monument.

See also

In Spanish: Nathan Bedford Forrest para niños

In Spanish: Nathan Bedford Forrest para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |