Cavalry in the American Civil War facts for kids

The American Civil War was a huge conflict in American history. During this war, the way cavalry (soldiers on horseback) fought changed a lot. Instead of charging directly into enemy lines, cavalry became more focused on protecting their own army, launching quick attacks (raids), and gathering information (reconnaissance). This change happened because new, more accurate rifles were invented, making old-style cavalry charges very dangerous and not very effective.

At the start of the war, the Confederate (Southern) army had an advantage in cavalry. Many Southern men were already skilled at riding and shooting. Also, most experienced cavalry officers from the regular army chose to join the Confederacy.

However, by 1863, the Union (Northern) army caught up. They developed strong cavalry forces thanks to clever tactics by leaders like Benjamin Grierson and aggressive movements by Philip Sheridan.

Keeping cavalry units was very expensive. Sometimes, dishonest people would sell bad horses at very high prices, making it even harder for the armies.

Contents

Types of Horse Soldiers in the Civil War

During the Civil War, there were four main kinds of mounted (horse-riding) forces:

Cavalry: Fighting on Horseback

Cavalry soldiers mainly fought while riding their horses. They used short rifles called carbines, pistols, and sabers (swords). Only a small number of Civil War units truly fit this description. This was mostly true for Union forces in the Eastern part of the war early on. Confederate forces in the East usually didn't carry carbines or sabers. Some Confederate groups in the West used shotguns, especially at the beginning of the war.

Mounted Infantry: Riding to Fight on Foot

Mounted infantry rode horses to get around quickly, but they would get off their horses to fight on foot. They mainly used rifles. Later in the war, most units called "cavalry" actually fought like mounted infantry. For example, Colonel John T. Wilder's "Lightning Brigade" rode horses to reach battlefields quickly, like at the Battle of Chickamauga. But once there, they fought like regular infantry soldiers. At the Battle of Gettysburg, Union cavalry under John Buford also got off their horses to fight, but they still used traditional cavalry weapons and formations.

Dragoons: A Mix of Cavalry and Infantry

Dragoons were a mix of cavalry and infantry. They were armed like cavalrymen but were also expected to fight on foot. The name comes from the French army, meaning they were a cross between light infantry and light cavalry. Union General Philip Sheridan's forces in 1864 and Confederate General Wade Hampton's men after the Battle of Yellow Tavern fought like dragoons, even though they didn't use the name.

Irregular Cavalry: Partisan Rangers and Guerrillas

Irregular cavalry were often called partisan rangers or guerrillas. They were usually mounted forces. They used whatever weapons they could find. The Confederacy had the most famous irregular leaders, such as William Quantrill and John S. Mosby.

What Cavalry Did: Their Main Jobs

During the Civil War, cavalry had five main jobs, listed from most important to least important:

- Finding and Hiding Information: They scouted ahead to find the enemy and also screened their own army's movements to keep them secret.

- Delaying the Enemy: They fought defensive battles to slow down the enemy's advance.

- Chasing and Harassing: They pursued and bothered defeated enemy forces.

- Attacking: They sometimes launched direct attacks.

- Long-Distance Raids: They rode far behind enemy lines to destroy supply depots, railroads, and communication lines.

This was a big change from earlier wars, like the Napoleonic Wars, where cavalry often made huge charges to break enemy infantry lines. But with the new, accurate rifled muskets, a soldier could shoot many times before cavalry could reach them. Horses and riders were easy targets.

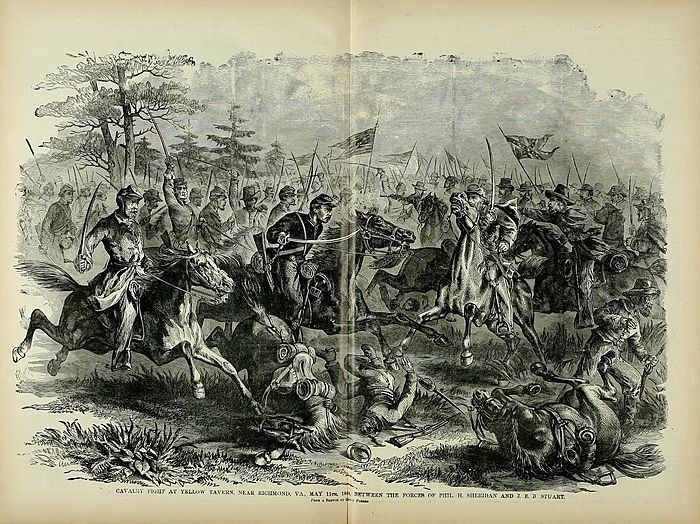

Still, cavalry did attack, especially against other cavalry units. Famous examples include the Battle of Brandy Station and the Battle of Yellow Tavern. Cavalry-on-cavalry fights happened at the First Battle of Bull Run and during Elon J. Farnsworth's charge at Gettysburg.

Reconnaissance (gathering information) was super important for cavalry. They were like the "eyes" of the army. For example, in the Gettysburg Campaign, Union cavalry tried to find the Confederate army invading the North. Confederate cavalry, led by J.E.B. Stuart, worked to hide their army's movements.

Long-distance raids were exciting for cavalrymen because they could bring fame. However, they often didn't have much strategic value. Jeb Stuart became famous for his bold raids in 1862. But during the Gettysburg Campaign, his raid actually weakened his army and left Robert E. Lee without enough information, which contributed to the Confederate defeat.

Union raids had mixed results. George Stoneman's raid was a failure. But Benjamin Grierson's raid during the Vicksburg Campaign was a brilliant success. It pulled Confederate forces away from Ulysses S. Grant's army. James H. Wilson's huge raid in 1865 showed what future armored warfare might look like. Generally, raids were more effective in the Western part of the war.

Cavalry also played a crucial role in defensive actions, like during the retreat from Gettysburg. Chasing and harassing enemy forces, though often overlooked, was done very well during the pursuit of Robert E. Lee in the Appomattox Campaign.

How Cavalry Units Were Organized

Cavalry regiments were made up of companies (later called "troops"), each with up to 100 men. Ten companies formed a regiment. Two or more companies could be grouped into battalions. Civil War regiments were often smaller than their full strength. They were usually grouped with two to four other regiments to form brigades. Two to four brigades then formed divisions. By the end of the war, the Union Army had 272 cavalry regiments, and the Confederate Army had 137.

Early in the war, most cavalry regiments were spread out and put under the command of infantry units. But as commanders realized how important long-range scouting and raiding were, they started to group more regiments into larger, separate cavalry units. Eventually, the Union Army of the Potomac had a Cavalry Corps with three divisions. The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, which grouped its cavalry earlier under J.E.B. Stuart, had a cavalry division.

Both armies' cavalry units were also supported by horse artillery (cannons pulled by horses) and their own supply wagons for ammunition and other needs.

Cavalry Equipment

Horses: The Cavalryman's Best Friend

The most important piece of equipment for a cavalryman was his horse. Both the North and South were hesitant to form mounted units at first because horses were so expensive. Each cavalry regiment cost $300,000 to start and over $100,000 each year to maintain.

At first, both sides required new recruits or local communities to provide horses. The North quickly changed this policy, but the South kept it throughout the war, even though it caused problems. Confederate soldiers owned their horses and were paid monthly for them. If a soldier's horse got sick, hurt, or died, he had to go home and replace it himself. If he didn't return with a new horse within 60 days, he had to become an infantryman, which was seen as a bad fate.

Union cavalrymen rode horses provided by the army. The Union army bought about 650,000 horses during the war, plus another 75,000 taken from Confederate territory.

Union army rules for cavalry horses said they had to be at least 15 hands (about 5 feet) tall, weigh at least 950 pounds, and be between 4 and 10 years old. They also had to be well-trained. Dark-colored male horses (geldings) were preferred. The Confederacy couldn't be as picky because they had fewer horses.

Horse prices changed during the war. In 1861, a cavalry horse cost up to $119. By 1865, prices were around $190. In the Confederacy, horses became very scarce and expensive, costing over $3,000 by the end of the war due to inflation. Union cavalry horses were given plenty of food each day, but sometimes the army's supply system couldn't deliver it where it was needed most.

Unfortunately, officers on both sides often didn't take good care of the animals. There was no organized veterinary corps (animal doctors) in the army, so diseases spread easily. The U.S. Congress created the rank of veterinary sergeant in 1863, but the pay was too low to attract qualified people. A proper U.S. army veterinary corps wasn't formed until 1916.

Horses gave cavalry units great speed. Sometimes, forces were pushed to their limits, like Jeb Stuart's raid in 1862, where his men marched 80 miles in 27 hours. Such long, fast marches were very hard on the units, and they needed long rest periods afterward. During the Gettysburg Campaign, Stuart's men had to take over 1,000 horses from local farmers because their own horses were worn out. Many of these new, untrained horses made fighting harder.

Weaponry: What Cavalry Carried

While some mounted forces used regular infantry rifles, cavalrymen, especially in the North, often carried three other types of weapons:

- Carbines: These were shorter rifles, easier to carry and use from horseback. They were less accurate than long rifles. Most carbines were single-shot weapons that loaded from the back. The most common ones were the Sharps rifle, the Burnside carbine, and the Smith carbine. Later in 1863, the seven-shot Spencer repeating carbine was introduced. Union Colonel John T. Wilder equipped his entire brigade with these, earning them the nickname "Lightning Brigade" for their speed. One Confederate soldier joked that Wilder's men could "load on Sunday and fire all week."

- Pistols: These were usually six-shot revolvers, made by Colt or Remington. They were good for close-up fighting but not very accurate from a distance. It was common for cavalrymen to carry two revolvers for extra firepower. John Mosby's men often carried four each!

- Sabers: These were swords used by cavalrymen on both sides. They were often used to scare opponents more than as practical weapons. Many Confederate cavalrymen thought sabers were old-fashioned and not useful in modern battles. One Southern commander even said the only time he used his saber was to roast meat over a fire! However, sabers were used a lot in battles like Battle of Brandy Station and the Gettysburg cavalry battles. South Carolina cavalry and General Wade Hampton's men loved using their sabers.

- Shotguns: These were used early in the war, especially by the Confederacy. They caused a lot of damage up close but were mostly replaced by carbines once armies had enough supplies.

- Lances: These long spears were used by a few cavalry regiments, like the 5th Texas Cavalry and the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Lances had been used since medieval times but became useless with the invention of the Minié ball (a type of bullet). The 5th Texas Cavalry tried the only major lancer charge of the war at the Battle of Valverde and suffered heavy losses, abandoning lances afterward. The 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry stopped using lances in May 1863.

Confederate Cavalry: Southern Horsemen

Many people believed that Southerners were better horsemen than Northerners, especially at the start of the war. Roads in the rural South were often poor, so horses were used more for everyday travel. Also, Southern society had a strong tradition of militias and "slave catcher" patrols, which meant more mounted units existed before 1861.

Confederate soldiers owned their horses and were paid monthly for them. If a soldier's horse was sick, injured, or killed, he had to go home and replace it at his own cost. If he didn't return with a new horse within 60 days, he was forced to become an infantryman, which was considered a disgrace.

The first famous Confederate cavalry leader was J. E. B. Stuart. He was known for his flashy style and bold commands. He became very popular in the South for riding all the way around the Union Army of the Potomac twice. These long-range missions didn't achieve much militarily but greatly boosted Southern morale. After Stuart's death in 1864, Wade Hampton took over and was arguably a more effective commander. Another notable Eastern commander was Turner Ashby, known as the "Black Knight of the Confederacy," who led Stonewall Jackson's cavalry in the Valley Campaign. He was killed in battle in 1862.

In the Western Theater, Nathan Bedford Forrest was a fearless and tough cavalry commander. He achieved amazing results with small forces but often didn't work well with the main army commanders. John Hunt Morgan had similar issues. In the East, the Partisan Ranger John S. Mosby managed to tie down thousands of Federal troops with only 100-150 irregulars. In the Trans-Mississippi Theater, John S. Marmaduke and "Jo" Shelby became important leaders.

Union Cavalry: Northern Horsemen

The Union Army started the war with five regular mounted regiments. These were later renumbered as the 1st through 5th U.S. Cavalry regiments, and a 6th was added. The Union was initially slow to create more cavalry because it was expensive and training a good cavalryman could take up to two years. Also, many thought the rough, forested land in the U.S. wasn't good for large cavalry forces like those in Europe. As the war went on, the value of cavalry became clear, especially for scouting and raiding. Many state volunteer cavalry regiments were then added to the army. The Union eventually had about 258 mounted regiments and 170 separate companies, and they suffered 10,596 killed and 26,490 wounded.

The Union cavalry faced challenges at the start. Northern soldiers supposedly had less riding experience than Southerners. Also, the Union army didn't test recruits' horsemanship until August 1862. More than half (104 out of 176) of the experienced U.S. Army cavalry officers had left to fight for the Confederacy. One advantage Union horsemen had was that the army provided their horses, so they didn't have to worry about replacing an injured one. Commanders often tried to get specific horse breeds, with the Morgan being a favorite. Famous Morgan cavalry horses included Sheridan's "Rienzi" and Stonewall Jackson's "Little Sorrel."

Early in the war, Union cavalry forces were often used for simple tasks like guarding posts, delivering messages, or protecting officers. The first officer to use Union cavalry effectively was Major General Joseph Hooker. In 1863, he put all the cavalry forces of his Army of the Potomac under one commander, George Stoneman.

By the summer of 1863, the Union cavalry truly came into its own. It was seen as less skilled than the Southern cavalry until then. The Battle of Brandy Station, though not a clear victory, is seen as the point where the Union cavalry proved it was just as capable.

In 1864, Philip Sheridan took command of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac. He used his horsemen in a more strategic way. Even though his superior, Major General George Meade, was hesitant, Sheridan convinced General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant to let him lead long-range raids. The first of these, at Yellow Tavern, resulted in the death of Confederate commander Jeb Stuart. Sheridan later used his cavalry effectively in the Valley Campaigns of 1864 and the Appomattox Campaign, chasing Robert E. Lee.

In the Western Theater, two effective Union cavalry generals, Benjamin Grierson and James H. Wilson, are not as famous as their Eastern counterparts. Grierson's dramatic raid through Mississippi was a key part of Ulysses S. Grant's Vicksburg Campaign. Wilson was crucial in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign and his 1865 Alabama raid.

Important Cavalry Battles and Raids

Here are some Civil War battles, campaigns, or raids where cavalry played a very important role:

- Battle of Brandy Station — In 1863, this was the largest cavalry battle of the war, with 20,500 soldiers.

- Battle of Chancellorsville — A plan for a raid behind Confederate lines failed due to George Stoneman's inaction.

- Battle of Gaines's Mill — The first big cavalry fight of the war.

- Battle of Gettysburg, Third Day cavalry battles — Included fights at East Cavalry Field and Farnsworth's Charge.

- Battle of Franklin — James H. Wilson's defense against Forrest likely saved the Union army.

- Battle of Mine Creek — In 1864, this was the largest cavalry battle west of the Mississippi, with 9,600 cavalry.

- Battle of Sailor's Creek — Clever cavalry moves led to Confederates being close to surrender in the Appomattox Campaign.

- Battle of Selma — James H. Wilson's huge raid into Alabama in 1865.

- Battle of Trevilian Station — In 1864, Sheridan led the largest all-cavalry battle of the war, with 16,048 cavalry.

- Battle of Yellow Tavern — Confederate commander J.E.B. Stuart was killed by Philip Sheridan's cavalry.

- Dahlgren's Raid — An unsuccessful Union raid against Richmond.

- Gettysburg Campaign — Many cavalry actions happened during Robert E. Lee's invasion of Pennsylvania.

- Grierson's Raid — A long-range raid through Mississippi that helped Ulysses S. Grant's Vicksburg Campaign.

- Maryland Campaign — J.E.B. Stuart's second ride around the Union army.

- Peninsula Campaign — Stuart's first ride around the Union army.

- Price's Raid — Sterling Price's 1864 raid in the Trans-Mississippi Theater.

- Streight's Raid — An 1863 raid where Colonel Abel Streight surrendered 1,500 men to Forrest's 400.

- Third Battle of Winchester — In 1864, Sheridan fought Early in the Shenandoah valley with 9,300 cavalry.

- Wilson's Raid — James H. Wilson's 1865 raid through Alabama and Georgia.

- Morgan's Raid — John H. Morgan's 1863 raid through Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio.

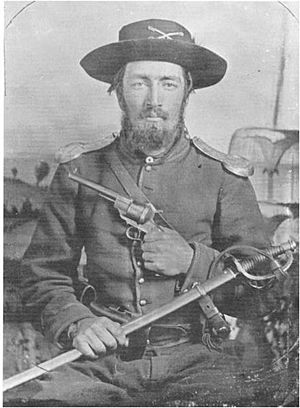

Famous Cavalry Leaders and Partisan Rangers

|

|

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |