Jackson's Valley campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Jackson’s Valley campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

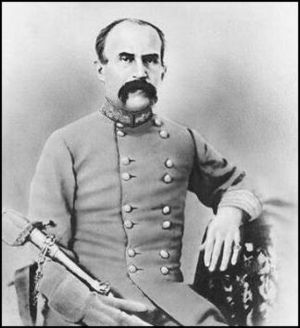

Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, commander of the Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley campaign of 1862 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Nathaniel P. Banks John C. Frémont Irvin McDowell |

“Stonewall” Jackson | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 52,000 (June 1862) | 17,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5,307 | 2,677 | ||||||

The Jackson's Valley campaign, also known as the Shenandoah Valley campaign of 1862, was a series of clever military moves by Confederate General Stonewall Jackson. It happened in the spring of 1862 in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia during the American Civil War.

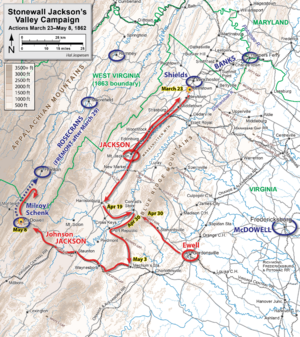

Jackson's army of about 17,000 soldiers moved very quickly and unexpectedly. They marched 646 miles (1,040 km) in just 48 days. During this time, they fought and won several smaller battles. They faced three different Union armies that had a total of 52,000 soldiers. Jackson's main goal was to stop these Union forces from joining a bigger attack on Richmond, the Confederate capital. He succeeded in this goal.

Jackson's first battle was a loss at the First Battle of Kernstown on March 23, 1862. But this defeat actually helped the Confederates. It made Union President Abraham Lincoln send more troops to the Valley. These troops were originally meant to help the Union attack on Richmond. After Kernstown, Jackson used maps made by Jedediah Hotchkiss to gain a big advantage in knowing the land.

Later, Jackson moved west and defeated part of a Union army at the Battle of McDowell on May 8. This stopped two Union armies from joining forces against him. He then moved back down the Valley. On May 23, he captured the Union base at Front Royal. This made the Union general, Nathaniel P. Banks, retreat. On May 25, Jackson defeated Banks again at the First Battle of Winchester. He chased Banks's army all the way into Maryland.

Union generals James Shields and John C. Frémont tried to trap Jackson. But Jackson skillfully pulled his army back up the Valley. On June 8, his general Richard S. Ewell defeated Frémont at the Battle of Cross Keys. The next day, Jackson's forces joined Ewell's to defeat Shields at the Battle of Port Republic. This battle ended the campaign.

After his success, Jackson quickly marched his troops to join General Robert E. Lee. They fought together in the Seven Days Battles near Richmond. Jackson's bold campaign made him a very famous general in the Confederacy. His tactics are still studied by military leaders today.

Contents

- Why the Valley Was Important

- Who Fought in the Valley?

- How the Campaign Began

- Key Battles and Movements

- Battle of Kernstown: A Surprising Start

- Jackson's Clever Retreat

- Battle of McDowell: Fighting in the Mountains

- Tricky Orders and Smart Moves

- Battle of Front Royal: A Sneaky Attack

- Battle of Winchester: Chasing the Enemy

- Union Armies Try to Catch Jackson

- Battle of Cross Keys: Holding the Line

- Battle of Port Republic: The Final Clash

- What Happened Next?

- See also

Why the Valley Was Important

In the spring of 1862, the Confederate side was not doing well. Union armies were winning battles in the west. A huge Union army was also moving toward Richmond, the Confederate capital. Another Union army was threatening the Shenandoah Valley.

However, Jackson's Confederate soldiers were in good spirits. Their actions in the Valley helped stop the Union plans. This also gave a boost to the Confederate morale everywhere.

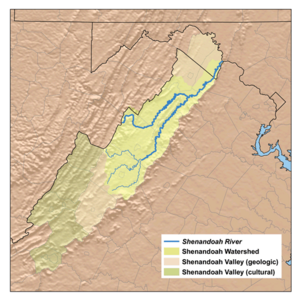

The Shenandoah Valley was very important during the Civil War. It was a long valley between the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Allegheny Mountains. It stretched about 140 miles. The Valley offered two key advantages to the Confederates. First, it was a good place to launch surprise attacks on Union armies. Second, it was a protected path for Confederate armies to march north into Pennsylvania. General Robert E. Lee used this route in 1863.

The Valley was also rich in farms and livestock. It provided food for Virginia's armies and for Richmond. If the Union could control the Valley, it would be a big loss for the Confederates. Jackson himself wrote, "If this Valley is lost, Virginia is lost."

Who Fought in the Valley?

The Confederate Army

| Confederate Commanders |

|---|

|

Stonewall Jackson's army grew during the campaign. It started with only about 5,000 soldiers. By June 1862, it reached about 17,000 men. Even with these reinforcements, Jackson's army was much smaller than the Union forces. The Union had about 52,000 men in total.

Jackson's command included famous units like the Stonewall Brigade. He also had cavalry led by Colonel Turner Ashby. Other important generals under Jackson included Richard S. Ewell and Edward "Allegheny" Johnson.

The Union Army

| Union Department Commanders |

|---|

|

| Key Union Subordinates |

|---|

|

The Union forces in the Valley changed a lot. Different armies arrived and left. These forces were usually from three separate commands. This made it harder for them to work together against Jackson.

Initially, Major General Nathaniel P. Banks was in charge of the Valley. His force included divisions led by James Shields and Alpheus S. Williams. Later, Shields's division was moved to another command.

Major General John C. Frémont commanded the Mountain Department, west of the Valley. Parts of his army faced Jackson at the Battle of McDowell.

Major General Irvin McDowell was also ordered to send troops to the Valley. This included Shields's division returning to the area.

How the Campaign Began

In November 1861, Jackson took command of the Valley District. His headquarters were in Winchester. Jackson knew the Valley well because he had lived there for many years. His army was small at first.

In early 1862, Union General George B. McClellan ordered Banks to move his troops across the Potomac River. Banks moved south toward Winchester. Jackson's army was part of a larger Confederate force. When that force moved away, Jackson's position became isolated. He began to pull his troops back "up" the Valley. This meant moving to the higher ground in the southwest. He did this to protect the main Confederate army.

By March 12, 1862, Banks occupied Winchester. Jackson had already left the town. On March 21, Jackson learned that Banks was splitting his forces. Many Union troops were leaving the Valley. This meant fewer soldiers were left to guard the area. Jackson saw an opportunity to strike.

Key Battles and Movements

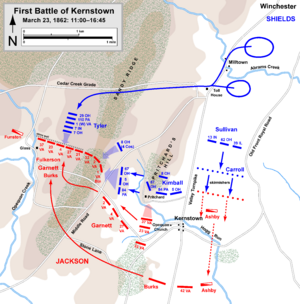

Battle of Kernstown: A Surprising Start

Jackson's orders were to stop Banks's forces from leaving the Valley. So, Jackson turned his men around. They marched quickly, covering 40 miles in two days. They arrived at Kernstown on the morning of March 23.

Jackson thought he was attacking a small Union force of about 3,000 men. But he was wrong. He was actually attacking almost 9,000 Union soldiers. The Union commander, General Shields, had been wounded. Colonel Nathan Kimball was now in charge.

Jackson attacked the Union position. His main force tried to go around the Union right side. Kimball moved his troops to block this. The Confederates reached a stone wall and fired fiercely. Jackson realized the Union force was much larger. He sent more troops to his left. But by then, his soldiers were running out of ammunition. They had to retreat.

The Union won the battle, but it was a strategic victory for the Confederates. President Lincoln was worried by Jackson's bold attack. He sent Banks and more troops back to the Valley. He also held back a large Union corps that was supposed to help McClellan attack Richmond. McClellan later said this stopped him from taking Richmond. So, Jackson's only loss in his military career turned into a big win for the Confederacy.

After the battle, Jackson arrested General Richard B. Garnett for retreating without permission. He was replaced by General Charles S. Winder.

Jackson's Clever Retreat

After Kernstown, Union forces chased Jackson. But Banks stopped the chase due to supply problems. Jackson retreated to Mount Jackson. There, he asked Captain Jedediah Hotchkiss to make a detailed map of the Valley. This map gave Jackson a big advantage in the battles to come.

Banks continued to advance slowly. Jackson kept moving his army further up the Valley to Harrisonburg. Banks then controlled the Valley as far south as Harrisonburg.

President Lincoln decided to move Shields's division away from Banks. This left Banks with only one division in the Valley. Banks was told to retreat and take a defensive position.

Meanwhile, Jackson received new orders. He was told to stop Banks from taking Staunton. He also received reinforcements: 8,500 men under Major General Richard S. Ewell. Jackson and Ewell planned their next moves.

Jackson also had some problems with his own officers. He arrested Garnett and had a disagreement with Turner Ashby. But Jackson eventually smoothed things over.

Jackson's plan was to have Ewell threaten Banks. Jackson's own force would move to help General Edward "Allegheny" Johnson. Johnson was fighting a Union advance toward Staunton. Jackson wanted to defeat the Union armies one by one before they could combine. He moved his troops quickly and secretly. On May 5, Jackson's army camped near Staunton.

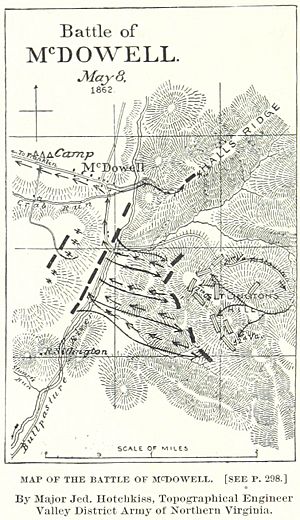

Battle of McDowell: Fighting in the Mountains

On May 8, Jackson arrived at McDowell. He found Johnson's troops fighting. About 6,000 Union soldiers were camped in the village. A hill called Sitlington Hill overlooked the Union position. Jackson's army had about 10,000 men.

The Union generals realized they were outnumbered. They also thought Jackson could use artillery from the hill. (They didn't know Jackson couldn't bring his cannons up the steep hill.) So, to buy time to retreat, the Union decided to attack the hill first.

Around 4:30 p.m., 2,300 Union troops attacked Sitlington Hill. They almost broke Johnson's line. Jackson sent in more infantry and pushed them back. The fighting continued until about 10 p.m. Then, the Union troops pulled back.

The Union generals retreated north from McDowell early on May 9. Jackson tried to chase them, but they were too far ahead. The Union lost 259 men, while the Confederates lost 420. This was one of the few times in the Civil War that the attacker lost fewer men than the defender.

Tricky Orders and Smart Moves

After McDowell, General Ewell was confused by many orders. He received orders from both Jackson and General Joseph E. Johnston. Jackson wanted Ewell to chase Banks. Johnston wanted Ewell to leave the Valley and go to Richmond.

Ewell met with Jackson on May 18. They decided to attack Banks's army. Banks now had fewer than 10,000 men. Jackson asked Robert E. Lee for help. Lee convinced President Jefferson Davis that a win in the Valley was more important right then. Johnston then changed his orders. He told Ewell to stop Banks's troops from joining McDowell's.

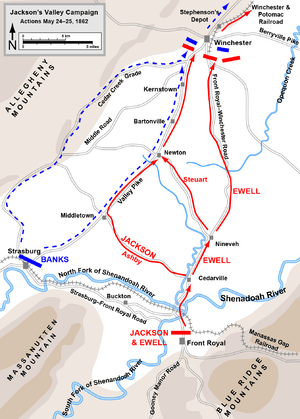

On May 21, Jackson marched his army east. He joined Ewell's forces on May 22. They then moved down the Luray Valley. Their fast marches earned Jackson's soldiers the nickname "Jackson's foot cavalry." Jackson sent cavalry ahead to make Banks think he was attacking Strasburg. But Jackson's real plan was to first attack the small Union outpost at Front Royal. This would make Banks's position at Strasburg impossible to hold.

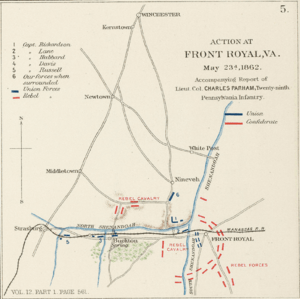

Battle of Front Royal: A Sneaky Attack

On May 23, Confederate cavalry captured a Union supply depot and cut telegraph wires. This isolated Front Royal from Banks. Jackson led his infantry on a hidden path to approach Front Royal. He saw that the Union troops would have to cross two bridges to escape.

The battle began around 2 p.m. The Confederates quickly pushed the small Union force out of town. The Union commander, Colonel John Reese Kenly, tried to make a stand. But he saw Confederate cavalry approaching the bridges he needed for escape. He ordered his men to abandon their position. They crossed the bridges and set the last one on fire.

Jackson ordered his troops to cross the burning bridge. He was frustrated that his cannons were delayed. A group of 250 Confederate cavalry arrived. Jackson sent them to chase Kenly. The cavalry charged the Union line and routed them.

The battle was a big win for the Confederates. The Union lost 773 men, mostly captured. The Confederates lost only 36. Jackson's men also captured many Union supplies. Banks became known as "Commissary Banks" because of all the supplies Jackson took from him.

This battle had a huge impact. President Lincoln decided to send 20,000 men from McDowell's corps to the Valley. These troops were supposed to reinforce McClellan's attack on Richmond. Lincoln wired McClellan, saying he had to stop McDowell's movement because of Banks's critical situation.

Battle of Winchester: Chasing the Enemy

On May 24, Jackson planned to cut off Banks's retreating army. He sent cavalry to watch the roads. He also ordered Ewell to move his main force toward Winchester.

Confederate forces reached Middletown and began firing cannons at the Union column. The Union troops were thrown into chaos. Jackson's men chased the Union army long after dark. Jackson reluctantly let his exhausted men rest for two hours.

On May 25, Jackson's troops woke up at 4 a.m. to fight again. Jackson found that Banks had not properly defended a key hill south of Winchester. He ordered the Stonewall Brigade to take the hill. They faced heavy fire but held their ground.

Jackson ordered another brigade to attack a hill to the southwest. These soldiers charged up the steep slope and over a stone wall. At the same time, Ewell's men attacked the far left of the Union line. The Union lines broke, and the soldiers retreated through the town streets. Jackson was so excited he rode cheering after the enemy. He shouted, "Go back and tell the whole army to press forward to the Potomac!"

The Confederate chase was not very effective. Jackson's cavalry had gone off to chase a small Union group. The Union soldiers fled 35 miles in 14 hours, crossing the Potomac River into Williamsport, Maryland. The Union lost over 2,000 men, mostly captured. The Confederates lost about 400.

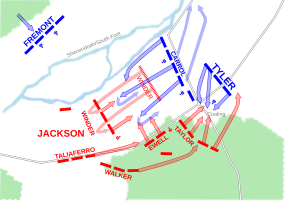

Union Armies Try to Catch Jackson

News of Banks's defeat worried Washington. President Lincoln feared Jackson might attack the capital. Lincoln planned a big offensive. He ordered Frémont to march to Harrisonburg to fight Jackson. He also told McDowell to send 20,000 men to the Shenandoah Valley. Their goal was to capture Jackson and Ewell.

Lincoln's plan was to trap Jackson between three armies. Frémont would be on Jackson's supply line. Banks would chase Jackson if he moved up the Valley. McDowell's troops would attack Jackson from Front Royal. This would crush Jackson's army against Frémont's.

But Lincoln's plan was complicated. McDowell was not eager to go to the Valley. Frémont moved slowly on bad roads. Instead of going to Harrisonburg, he went north. This meant the Union could only hope for a pincer movement at Strasburg. This would require perfect timing.

Jackson learned about Shields's return on May 26. He moved his army back to Winchester. Lincoln's plan continued to fall apart. Banks said his army was too shaken to move. Frémont was slow. Shields would not leave Front Royal until more troops arrived. Jackson reached Strasburg before either Union army.

On June 2, Union forces chased Jackson. McDowell went up the Luray Valley. Frémont went up the main Valley. Jackson's men marched very fast. But heavy rains and mud slowed the Union pursuers. For the next five days, there were many small fights between Jackson's cavalry and Union cavalry. Jackson's cavalry also burned some bridges. This slowed the Union chase and kept Shields's and Frémont's forces separated.

On June 6, Jackson's cavalry commander, Turner Ashby, was killed in a skirmish. This was a big loss for the Confederates. Jackson later wrote that Ashby was one of the best cavalry officers he knew.

As the two Union armies got closer, Jackson had a choice. He could escape through Brown's Gap and march to Richmond. But he wanted to defeat the two Union armies. He realized that Port Republic was key. If he could hold the bridges there, he could stop the Union armies from joining. He placed most of his army south of the town. He sent Ewell's division to a ridge near Cross Keys, ready to face Frémont.

On June 7, Ewell tried to get Frémont to attack him. But Frémont was cautious. On June 8, Jackson hoped to avoid fighting on Sunday. But Union cavalry almost captured Confederate supplies and Jackson himself at Port Republic.

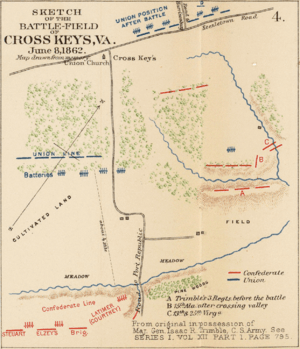

Battle of Cross Keys: Holding the Line

Frémont moved carefully toward Ewell's position on the morning of June 8. He thought he was outnumbered, but he actually had more men (11,500 to 5,800). His men were delayed by Confederate skirmishers. Frémont's cannons started firing around 10 a.m. This only alerted Jackson at Port Republic that the battle had begun.

Frémont's men advanced. Around noon, a Union brigade attacked. They were surprised by heavy musket fire. The 8th New York Infantry lost almost half its men.

By mid-afternoon, Frémont had sent only a few of his regiments into battle. Ewell expected another attack. One of Ewell's generals, Isaac R. Trimble, launched his own attack against a Union cannon position. He and his men waited there, but no attack came. Frémont pulled his men back. Ewell decided not to counterattack because he was outnumbered. The Confederates moved to the previous Union position. The battle was more of a skirmish. The Union lost 684 men, while the Confederates lost only 288.

Jackson's plan for June 9 was to combine his forces and defeat Shields at Port Republic. He believed Frémont would not attack again. So, he ordered most of Ewell's division to leave under cover of darkness. They crossed the North River bridge. A quickly built bridge allowed them to cross the South River. The Stonewall Brigade led the advance toward Shields. Jackson also ordered his supply wagons to move into Brown's Gap.

Battle of Port Republic: The Final Clash

Jackson learned at 7 a.m. that Union troops were approaching. Without waiting for all his troops, he ordered the Stonewall Brigade to charge through the fog. The brigade was caught between cannons and rifle fire. They fell back in confusion. They had run into 3,000 Union soldiers under General Erastus B. Tyler.

Jackson realized the Union cannons were on a hill called the Coaling. He sent two regiments up the hill. They met three Union regiments and were pushed back.

Jackson ordered the rest of Ewell's division to cross the North River bridge and burn it. This kept Frémont's men separated. While waiting for these troops, Jackson reinforced his line. He ordered General Richard Taylor to attack the Union cannons again. The Stonewall Brigade charged again but was routed.

Then, Ewell arrived. He ordered two regiments to attack the Union line's left side. Tyler's men fell back. Taylor attacked the cannons on the Coaling three times before finally taking it. But then, three Ohio regiments charged. It was only when Ewell's troops appeared that Tyler decided to retreat. The Confederates began firing cannons at the retreating Union troops. More Confederate reinforcements arrived. The Union army slowly pulled back. Jackson said, "General, he who does not see the hand of God in this is blind, sir, blind."

The Battle of Port Republic was not well managed by Jackson. It was the most costly battle for the Confederates. They lost 816 men against a Union force half their size. The Union lost 1,002 men, many of them captured. Union soldiers were unhappy with their commanders, Shields and Frémont. Both of their military careers declined after this.

What Happened Next?

After Jackson's wins at Cross Keys and Port Republic, the Union forces retreated. Frémont marched back to Harrisonburg. Jackson's cavalry chased Frémont's retreat. Shields slowly marched to Front Royal.

Jackson asked Richmond for more troops. He wanted to go on the attack across the Potomac River. Lee sent him about 14,000 reinforcements. But then Lee told Jackson his real plan. He wanted Jackson to come to Richmond. Jackson would help attack McClellan's Union army and push it away from Richmond.

Shortly after midnight on June 18, Jackson's men began marching toward Richmond. They fought with Lee in the Seven Days Battles. Jackson's performance in these battles was not as strong as usual. This might have been because of how tired he was from the Valley campaign and the long march to Richmond.

Jackson's Valley campaign was a great success. He became the most famous Confederate soldier. His victories boosted the morale of the Southern public. He pushed his army to travel 646 miles (1,040 km) in 48 days. He won five important battles with about 17,000 men against over 50,000 Union soldiers. Jackson achieved his difficult goal. He made Washington hold back over 40,000 troops from McClellan's attack.

On the Union side, there were big changes in command. Lincoln was frustrated by the problems of controlling many different forces. He created a new army, the Army of Virginia. This army included the units of Banks, Frémont, and McDowell. This new army was later defeated by Lee and Jackson.

See also

In Spanish: Campaña de Jackson's Valley para niños

In Spanish: Campaña de Jackson's Valley para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |