Richard Taylor (Confederate general) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

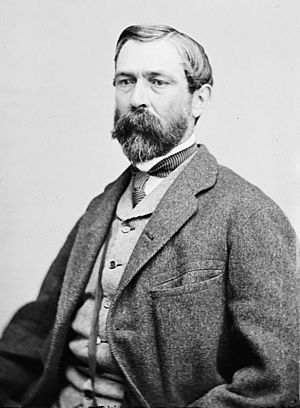

Richard Taylor

|

|

|---|---|

Photo taken between 1860 and 1870

|

|

| Born | January 27, 1826 Jefferson County, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | April 12, 1879 (aged 53) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | Confederate States of America |

| Service/ |

Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General (CSA) |

| Commands held | 9th Louisiana Infantry "Louisiana Tigers" |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Other work | Louisiana State Senate (1855–1861) |

Richard "Dick" Taylor (born January 27, 1826 – died April 12, 1879) was an American plantation owner, a politician, and a general for the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. He was also a military historian.

When the Civil War started, Taylor joined the Confederate States Army. He first led a group of soldiers in Virginia. Later, he commanded an army in the area west of the Mississippi River, known as the Trans-Mississippi Theater. In 1864, he led troops in West Louisiana during the Red River Campaign. He was the only son of Zachary Taylor, who was the 12th president of the United States. After the war, Richard Taylor wrote a book about his experiences.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Richard Taylor was born in 1826 at Springfield, his family's plantation near Louisville, Kentucky. His father was Zachary Taylor, a military officer, and his mother was Margaret Mackall Smith Taylor. Richard was named after his grandfather, Richard Lee Taylor, who fought in the American Revolutionary War.

Richard, often called "Dick," had five older sisters. The family moved a lot because his father was a career soldier who commanded forts on the American frontier. Richard went to private schools in Kentucky and Massachusetts.

He started college at Harvard College and finished at Yale in 1845. He didn't focus on grades but spent most of his time reading books about history, especially military history.

In 1846, during the Mexican–American War, Taylor visited his father in Mexico. He offered to help his father as an aide.

Plantation Life and Politics

Because of rheumatoid arthritis, a condition that affects joints, Taylor had to leave the war. He then managed his family's cotton plantation in Jefferson County, Mississippi. In 1850, he convinced his father, who was then president, to buy a large sugar cane plantation in St. Charles Parish, Louisiana. After his father died suddenly in 1850, Taylor inherited the sugar plantation.

In 1851, Richard Taylor married Louise Marie Myrthe Bringier. She was from Louisiana. Taylor made his plantation bigger and improved its sugar production. He also expanded the number of enslaved people working on his land to almost 200. This made him one of the wealthiest men in Louisiana. However, a big freeze in 1856 ruined his crop, putting him in debt.

In 1855, Taylor became involved in politics. He was elected to the Louisiana State Senate and served until 1861. He was part of different political parties, including the Whig Party and the Democratic Party. He was a delegate to the Democratic Convention in 1860, where he saw the party split apart.

American Civil War

When the American Civil War began, General Braxton Bragg asked Taylor to help him in Pensacola, Florida. Bragg knew Taylor and thought his knowledge of military history would be useful. Taylor had been against states leaving the Union, but he accepted the role.

While training new soldiers, Taylor was made a colonel of the Confederate 9th Louisiana Infantry Regiment. The soldiers chose him because they thought his connection to President of the Confederate States Jefferson Davis (who was married to Taylor's late sister) would help them get into battle faster. On July 20, he arrived in Richmond, Virginia, with his regiment. They were ordered to join the First Battle of Manassas, but they arrived hours after the Confederates had won.

Shenandoah Valley Campaign

On October 21, 1861, Taylor was promoted to brigadier general. He commanded a Louisiana brigade under Richard S. Ewell in the Shenandoah Valley campaign. This campaign was led by Stonewall Jackson. Jackson often used Taylor's brigade as a special attack force. They marched quickly and made swift attacks on the enemy's sides. Taylor led his soldiers in important attacks at the Battle of Front Royal on May 23, the First Battle of Winchester on May 25, and the Battle of Port Republic on June 9.

His brigade included various Louisiana regiments, like Major Chatham Roberdeau Wheat's "Louisiana Tigers" battalion. These soldiers were known for fighting hard and being tough outside of battle. Taylor helped to bring more order to the Tigers.

Taylor's brigade then went with Jackson's command to fight in the Seven Days Battles near Richmond. However, his rheumatoid arthritis made him unable to command for days. He missed the Battle of Gaines Mill, and the officer who took his place was killed.

Command in Louisiana

Taylor was promoted to major general on July 28, 1862. He was the youngest major general in the Confederacy. Some older commanders complained about this, but President Davis explained that Taylor was a strong leader and General Jackson had recommended him. Taylor was sent to Opelousas, Louisiana, to gather and train troops in the District of Western Louisiana.

A historian named John D. Winters wrote that Taylor was tasked with commanding all troops south of the Red River. His job was to stop the enemy from using the rivers and waterways in the area. He also had to gather new soldiers for Louisiana regiments fighting in Virginia and keep enough troops for his state.

Before Taylor returned to Louisiana, U.S. forces had raided much of southern Louisiana. In the spring of 1862, U.S. soldiers attacked and looted Taylor's Fashion plantation.

Taylor found his district almost empty of troops and supplies. But he made the best of it. He found two good commanders to help him: Alfred Mouton for infantry and Thomas Green for cavalry. These two were very important in Taylor's future battles.

In 1863, Taylor led a series of successful fights against U.S. Army forces for control of lower Louisiana. These included the Battle of Fort Bisland and the Battle of Irish Bend. These battles were against U.S. Major General Nathaniel P. Banks for control of the Bayou Teche area. Banks was trying to reach Port Hudson. After Banks pushed Taylor's army aside, Banks continued to Alexandria, Louisiana, before returning south to surround Port Hudson. Taylor then planned to take back Bayou Teche and the city of New Orleans, which would help stop the Siege of Port Hudson.

Battles to Retake New Orleans

Taylor planned to move down the Bayou Teche, capture lightly defended outposts and supply areas, and then take New Orleans. This would cut off Banks' U.S. army from their supplies. His plan was approved by the Secretary of War and President Jefferson Davis. However, Taylor's direct superior, Edmund Kirby Smith, thought it was better to focus on operations across the Mississippi River from Vicksburg.

Taylor marched his army to Richmond, Louisiana. There, he was joined by John G. Walker's Texas Division, known as "Walker's Greyhounds". Taylor ordered Walker's division to attack U.S. soldiers at two places on the Louisiana side of the Mississippi. These battles, the Battle of Milliken's Bend and the Battle of Young's Point, did not achieve the Confederate goals. After some early success at Milliken's Bend, U.S. gunboats shelled the Confederate positions, ending the fight. Young's Point also ended early.

After these battles, Taylor marched his army back to the Bayou Teche region. He captured Brashear City (Morgan City, Louisiana), gaining many supplies and new weapons. He moved close to New Orleans, which was lightly defended. While preparing to attack the city, he learned that Port Hudson had fallen. To avoid being trapped, he retreated his forces up Bayou Teche.

Red River Campaign

In 1864, Taylor defeated U.S. General Nathaniel P. Banks in the Red River Campaign. Taylor had a smaller force but won the Battle of Mansfield and the Battle of Pleasant Hill on April 8–9. He chased Banks back to the Mississippi River. For his success, the Confederate Congress thanked him. In these two battles, Taylor's trusted commanders, Alfred Mouton and Thomas Green, were killed. On April 8, 1864, Taylor was promoted to lieutenant general. This happened even though he had asked to be removed from command because he didn't trust his superior, General Edmund Kirby Smith.

End of the War

Taylor was given command of the Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana. After General John Bell Hood's army was badly defeated in Tennessee, Taylor briefly commanded the Army of Tennessee. Most of its remaining soldiers were sent to fight William Tecumseh Sherman's march through the Carolinas.

Taylor surrendered his department at Citronelle, Alabama, on May 4, 1865. This was almost a month after Appomattox Courthouse. He was released three days later. His remaining soldiers were released on May 12, 1865. In his book, "Destruction and Reconstruction," Taylor described his surrender. He mentioned a Union officer who seemed to think Southerners would quickly realize their mistakes. Taylor responded by proudly talking about his family's long history in America, including his ancestors fighting in the Revolutionary War and his father being president.

Military Prowess

Richard Taylor did not have military experience before the Civil War. However, many people who knew him, including his commanders and soldiers, often spoke about his great military skills. Nathan Bedford Forrest, another Confederate general, said about Taylor, "He's the biggest man in the lot. If we'd had more like him, we would have licked the Yankees long ago."

Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson and Richard S. Ewell often talked about their discussions with Taylor on military history, strategy, and tactics. Ewell said he learned a lot from Taylor. Stonewall Jackson even recommended promoting Taylor to major general. Taylor was one of only three lieutenant generals in the Confederacy who did not graduate from West Point, a famous military academy.

In his 1879 book, Taylor humbly explained how he became a better commander. He said he always studied the roads and areas around him, making rough maps and notes. He also imagined battles while marching, planning how to attack or defend. He learned from his mistakes and believed these habits helped him succeed.

Postwar Life

The war destroyed Taylor's home, his valuable library, and his sugar cane plantation. After the war, he moved his family to New Orleans. He lived there until his wife died in 1875. After her death, he moved with his three daughters to Winchester, Virginia. From there, he often traveled to visit friends in Washington, D.C., and New York City.

Taylor wrote a book called Destruction and Reconstruction: Personal Experiences of the Late War (1879). This book is considered one of the best accounts of the Civil War.

Taylor remained active in politics. He spoke with President Andrew Johnson to help get former Confederate President Jefferson Davis released from prison. Taylor was also a strong opponent of the Reconstruction policies after the war.

On April 12, 1879, he died from a serious illness in New York City. He was visiting a friend. Taylor's body was returned to Louisiana and buried at Metairie Cemetery in New Orleans.

Family

Richard Taylor was the only son of Margaret Mackall Smith and President Zachary Taylor. His sister Sarah Knox Taylor was the first wife of Jefferson Davis, but she died in 1835. Another sister, Mary Elizabeth, served as their father's hostess in the White House. Even though Richard Taylor joined the Confederacy, his uncle, Joseph Pannell Taylor, served as a Brigadier-General in the U.S. Army.

Richard and Marie Taylor had five children: two sons and three daughters. Their two sons died from scarlet fever during the Civil War. This was a very sad loss for both parents.

Legacy

- The Lt. General Richard Taylor Camp #1308, Sons of Confederate Veterans in Shreveport, Louisiana, is named after General Taylor.

- Jackson B. Davis, a former state senator, wrote an article about Taylor in 1941.

- A full biography about him, Richard Taylor, Soldier Prince of Dixie, was published in 1992 by T. Michael Parrish.

Works

- Taylor, Richard. Destruction and Reconstruction: Personal Experiences of the Late War. J.S. Sanders & Co., 2001 [1879]. ISBN: 1-879941-21-X.

See also

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |