George Armstrong Custer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

George Armstrong Custer

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service/ |

United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861–76 |

| Rank | Major General of Volunteers Lieutenant Colonel (Regular Army) |

| Commands held | Michigan Brigade 3rd Cavalry Division 7th U.S. Cavalry |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

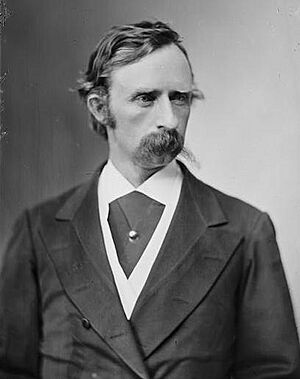

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer. He was a cavalry commander during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars.

When the Civil War began, Custer was a student at the United States Military Academy at West Point. His class graduated early so they could join the war. Custer finished last in his class. He served at the First Battle of Bull Run and later with Major General George B. McClellan in 1862. Early in the Gettysburg Campaign, Custer was promoted to Brigadier General of Volunteers at just 23 years old.

Custer stayed in the Army after the Civil War. He served as an officer in the Indian Wars. He died with all his men at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.

Contents

- Custer's Early Life and Family

- Education and West Point Years

- Custer in the Civil War

- After the Civil War

- Custer in the Indian Wars

- Politics and the Army

- The Battle of the Little Bighorn

- Custer's Personal Life

- Custer's Death

- Custer's Legacy

- Monuments and Memorials

- Dates of Rank

- See also

- Images for kids

Custer's Early Life and Family

Family Background and Name

Custer's family came to America from Germany around 1693. His mother's family had roots in England and Northern Ireland.

According to family letters, Custer was named after a minister, George Armstrong. His religious mother hoped he might become a clergyman.

Birth and Childhood Adventures

Custer was born in New Rumley, Ohio. His father, Emanuel Henry Custer, was a farmer and blacksmith. His mother was Marie Ward Kirkpatrick. He had two younger brothers, Thomas and Boston, and other siblings.

The Custer brothers loved playing practical jokes. Their father, Emanuel, was a strong supporter of the Democratic Party. He taught his children about politics and being tough from a young age. Once, when George (called Autie) was about four, he had to have a tooth pulled. His father told him to be a "good soldier." Even though it was painful, Autie didn't cry. Afterward, he proudly told his father they could "whip all the Whigs in Michigan!"

Education and West Point Years

To go to school, Custer lived with his older half-sister in Monroe, Michigan. Before West Point, he attended McNeely Normal School in Hopedale, Ohio. This school trained teachers. Custer even carried coal to help pay for his room and board. After graduating in 1856, he taught school in Cadiz, Ohio.

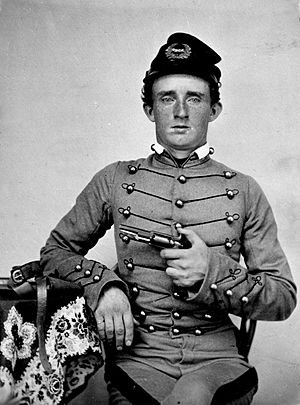

Custer joined West Point as a cadet on July 1, 1857. His class was supposed to study for five years. But the American Civil War started in 1861, so the course was shortened to four years. Custer graduated on June 24, 1861. He was 34th in a class of 34 graduates. Many classmates had dropped out or joined the Confederacy.

Custer often pushed boundaries and rules. In his four years at West Point, he got 726 demerits. This was one of the worst conduct records in the academy's history. A friend recalled Custer saying there were only two places in a class: the head and the foot. Since he didn't want to be the head, he aimed for the foot!

Custer in the Civil War

Early Service and Promotions

After graduating, Custer became a second lieutenant. He was assigned to the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. He helped train volunteers in Washington, D.C. He was at the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861. After getting sick, he rejoined his unit in February 1862.

In April 1862, Custer became an aide to Major General George B. McClellan. McClellan was leading the Army of the Potomac. During a pursuit of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, Custer showed his daring. When General John G. Barnard wondered how deep a river was, Custer rode his horse into the middle and shouted, "McClellan, that's how deep it is, General!"

Custer then led an attack across the Chickahominy River. His men captured 50 Confederate soldiers and the first Confederate battle flag of the war. General McClellan called it a "very gallant affair." Custer was promoted to captain in June 1862. He later participated in the Battle of Antietam in September.

In June 1863, Custer became an aide to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Pleasonton. Pleasonton commanded the Cavalry Corps. Custer said, "I do not believe a father could love his son more than General Pleasonton loves me." Pleasonton's first job was to find Robert E. Lee's army, which was moving north. This led to the Gettysburg Campaign.

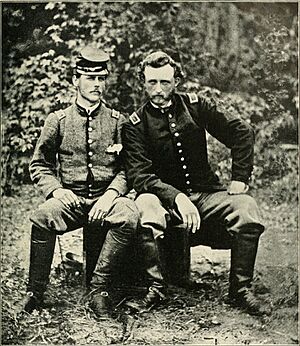

Leading the Michigan Brigade

On June 29, 1863, Pleasonton promoted Custer to brigadier general of volunteers. Custer was given command of the Michigan Cavalry Brigade, also known as the "Wolverines." At 23, he became one of the youngest generals in the Union Army. Even without much direct command experience, he quickly made his brigade reflect his aggressive style.

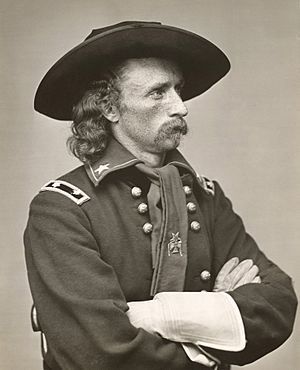

As a general, Custer could choose his uniform. He often wore a showy uniform. This wasn't just for looks. He wanted his men to easily spot him leading the way into danger on the battlefield. This helped boost their morale.

Key Battles: Hanover and Hunterstown

On June 30, 1863, Custer's brigade was near Hanover, Pennsylvania. They heard gunfire and found that another brigade was under attack. Custer quickly organized his troops and engaged the enemy. The rebels soon retreated. This skirmish delayed Confederate General Stuart from joining Lee's main army.

The next morning, July 1, Custer's men heard gunfire from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. They learned that General John Buford's cavalry had found Lee's army there. On July 2, Custer was ordered to go north to help the Union forces. Near Hunterstown, Pennsylvania, they met Stuart's cavalry.

Custer rode ahead alone to scout. He saw that the rebels didn't know his troops were nearby. He then carefully placed his men along the road, hidden. He also positioned his artillery. To lure the rebels, Custer rode directly at them with a small group of his men. As expected, over 200 rebel horsemen chased them. Custer's horse was shot, leaving him on foot. Private Norvell Francis Churchill rescued him. The pursuing rebels were then hit by rifle fire and cannons. Both sides pulled back.

After a long night, Custer's brigade arrived near Gettysburg around 3:00 a.m. on July 3. They were ordered to protect the Union flanks. This was where Custer would have some of his most important moments in the war.

The Battle of Gettysburg

Lee's plan at Gettysburg was to attack the Union forces from different sides. General Stuart was to attack from the southeast with 6,000 cavalrymen.

By mid-morning on July 3, Custer was east of Gettysburg. He was joined by Brigadier General David McMurtrie Gregg. Custer's men and Gregg's brigade, along with artillery, faced Stuart's larger force.

Around noon, Custer's men heard cannon fire. This was Stuart's signal to Lee. Soon, fighting began. Stuart ordered his mounted infantry to attack, but the Union line held. After a brief cannon exchange, there was a quiet period.

Around 1:00 p.m., a huge Confederate artillery attack began. Stuart's men attacked again. Custer sent his Fifth Michigan cavalry forward on foot, pushing the rebels back. The fighting became hand-to-hand. Custer then led a counterattack with the Seventh Michigan Cavalry. He shouted, "Come on, you Wolverines!" They charged, chasing the rebels until they hit a fence. The Confederates were then attacked from both sides. Custer's men pulled back to their artillery, which drove the Confederates away.

Around 3:00 p.m., Stuart's entire force advanced again. They were in a tight formation, looking very impressive. Stuart needed to break through the Union cavalry to reach the Union rear. Stuart's column easily passed some Union troops.

Stuart's last obstacle was Custer and his 400 veteran troopers of the First Michigan Cavalry. Custer was outnumbered but not afraid. He rode to the front, drew his saber, and shouted, "Come on, you Wolverines!" Custer's men charged. The collision was so sudden that many horses and riders were thrown. The Confederate advance stopped. Custer's men, along with others, attacked the rebel flanks. The rebel column broke apart.

Within twenty minutes, the Union artillery began firing on Pickett's men. Stuart knew his chance to join the main Confederate attack was gone. He pulled his men back. Custer's brigade lost 257 men at Gettysburg, the highest loss of any Union cavalry brigade. Custer wrote, "I challenge the annals of warfare to produce a more brilliant or successful charge of cavalry." He was promoted to major for his brave service.

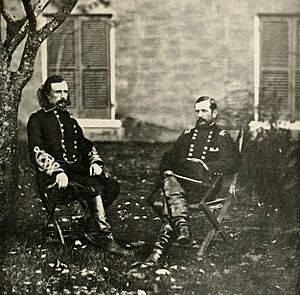

Shenandoah Valley and Appomattox

Custer also fought in General Philip Sheridan's campaign in the Shenandoah Valley. By the end of 1864, they had defeated Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early's army. Custer's division also took part in the Battle of Yellow Tavern, where Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart was badly wounded.

In the largest all-cavalry battle of the war, the Battle of Trevilian Station, Custer captured a Confederate supply train. But he was then cut off and suffered heavy losses before being rescued.

Sheridan and Custer later returned to the Siege of Petersburg. In April 1865, the Confederate lines broke. Robert E. Lee began his retreat to Appomattox Court House. Custer's division blocked Lee's retreat on the final day. They received the first flag of truce from the Confederates.

Custer was present at the surrender at Appomattox Court House. The table where the surrender was signed was given to him as a gift for his wife by General Sheridan. Custer's wife treasured this historic gift, which is now in the Smithsonian Institution. On April 15, 1865, Custer was promoted to major general in the U.S. Volunteers. At 25, he was the youngest major general in the Union Army.

After the Civil War

Reconstruction in Texas

After the war, Major General Custer took command of the 2nd Division of Cavalry. He marched his troops from Alexandria, Louisiana, to Hempstead, Texas. This was part of the Union occupation forces. Custer arrived in Texas in August 1865. He later moved his division to Austin.

During his time in Texas, Custer faced problems with his volunteer cavalry regiments. They were tired of fighting and wanted to leave the army. They didn't like Custer's strict discipline, especially since he was an officer from the Eastern Theater. Many of these veterans felt angry towards Custer.

New Opportunities and Politics

In February 1866, Custer left the U.S. volunteer service. He took a long break and explored new careers in New York City, like railroads and mining. He was offered a job as a general in the Mexican army, but he turned it down.

After his father-in-law died, Custer returned to Monroe, Michigan. He thought about running for Congress. He spoke out about how the American South should be treated after the Civil War, suggesting a moderate approach.

In September 1866, Custer traveled with President Andrew Johnson on a train tour. This trip was to gain public support for Johnson's policies toward the South. Custer and his wife stayed with the president for most of the trip.

Custer in the Indian Wars

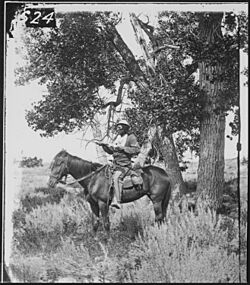

On July 28, 1866, Custer was appointed lieutenant colonel of the new 7th Cavalry Regiment. This regiment was based at Fort Riley, Kansas. He served on the frontier and scouted in Kansas and Colorado. He joined Major General Winfield Scott Hancock's expedition against the Cheyenne. In June, a small party of soldiers was attacked and killed by Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne warriors. Custer later found their bodies.

Custer was arrested and suspended for being absent without leave (AWOL) to see his wife. But Major General Sheridan asked for him to return for a winter campaign. Custer rejoined his regiment in October 1868.

Battle of Washita River

Under Sheridan's orders, Custer led the 7th Cavalry Regiment in an attack on the Cheyenne camp of Chief Black Kettle on November 27, 1868. This was the Battle of Washita River. Custer reported killing 103 warriors and taking 53 women and children prisoner. The Cheyenne said fewer warriors died, but many women and children were killed. Custer had his men shoot most of the 875 Indian ponies they captured. This battle was seen as an important U.S. victory. It helped force many Southern Cheyenne onto a U.S.-assigned reservation.

Dakota Territory and Gold Discovery

In 1873, Custer was sent to the Dakota Territory. His job was to protect a railroad survey party from the Lakota. On August 4, 1873, near the Tongue River, the 7th Cavalry had its first clash with the Lakota.

In 1874, Custer led an expedition into the Black Hills. He announced the discovery of gold on French Creek. This sparked the Black Hills Gold Rush. Towns like Deadwood, South Dakota, known for being wild, quickly appeared.

Politics and the Army

In 1875, the government tried to buy the Black Hills from the Sioux. When the Sioux refused, they were told to report to reservations by January 1876. But winter conditions made this impossible. The government called them "hostiles" and sent the Army to bring them in.

Custer was supposed to lead an expedition in the spring of 1876. But in March, he was called to Washington to testify at a congressional hearing. This hearing was investigating claims of corruption involving the Secretary of War and President Grant's brother. Custer provided information about these claims. His testimony caused a sensation.

Custer wanted to rejoin his regiment for the campaign. But President Grant ordered that another officer should lead Custer's military duty. General Terry, Custer's superior, argued that no other officer was qualified to replace Custer. Both Sheridan and Sherman supported Custer. General Sherman advised Custer to meet with Grant, but Grant refused to see him.

Custer left Washington to rejoin his regiment. A furious Grant ordered Sheridan to arrest Custer for leaving without permission. Custer's arrest caused public outrage. Grant eventually allowed Custer to lead his expedition, but only under General Terry's direct supervision. Custer was excited and told Terry's chief engineer that he would "cut loose" from Terry and act on his own.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn

By 1874, tensions between the U.S. and Plains Indian tribes like the Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne were very high. European-Americans kept breaking treaties and moving west. This led to violence from both sides. To take the Black Hills and stop Indian attacks, the U.S. decided to gather all remaining free Plains Indians. The government set a deadline for them to report to reservations. If they didn't, they would be considered "hostile."

Lieutenant Colonel Custer was in command of the 7th Cavalry Regiment. Custer and the 7th Cavalry left Fort Abraham Lincoln on May 17, 1876. They were part of a larger army force to round up the free Indians. Meanwhile, in the spring of 1876, the Lakota holy man Sitting Bull gathered many Plains Indians. They met at Ash Creek, Montana, to decide what to do about the white settlers. This large camp of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho Indians was the one the 7th Cavalry met at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

On June 22, Custer's regiment was sent to follow a large trail. On June 25, some of Custer's Crow Indian scouts spotted what they thought was a large Indian camp near the Little Bighorn River. Custer had planned to attack the next day. But since his presence was known, he decided to attack immediately. He divided his forces into three groups. Major Marcus Reno led one, Captain Frederick Benteen led another, and Custer led the third.

Reno charged the southern end of the village but stopped short. His men dismounted and formed a line. Lakota and Cheyenne warriors quickly attacked Reno's exposed side. Reno and his men had to retreat up the bluffs above the river, where they made a stand. This first part of the battle cost Reno a quarter of his men.

Custer may have seen Reno stop. Custer led his group to the northern end of the main camp. He might have planned to trap the Indians between his attack and Reno's. Some accounts say Custer's group tried to cross the river but were driven back by Indian sharpshooters. The soldiers were then chased by hundreds of warriors onto a ridge north of the camp. Crazy Horse prevented Custer and his men from digging in.

Hurrah boys, we've got them! We'll finish them up and then go home to our station.

Custer's men were likely spread out in fighting formations. But as the fight got worse, many soldiers might have held their own horses. This would have reduced their firepower. When Crazy Horse and White Bull charged, they broke through Custer's lines. Some soldiers panicked and ran towards a small hill where Custer and about 40 men were making a last stand. Warriors rode them down, hitting them with whips or lances.

Custer had 208 officers and men under his direct command. Reno had 142, Benteen had over 100, and 50 soldiers were with the supply train. The Lakota-Cheyenne forces may have had over 1,800 warriors. Some estimates from battle participants were even higher, averaging around 3,500 Indian warriors.

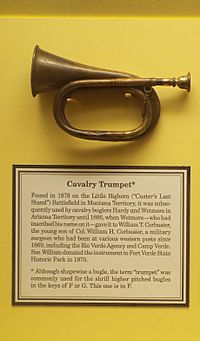

As Custer's soldiers were killed, the Native warriors took their weapons and ammunition. The soldiers' firing decreased, while the Indians' firing increased. The remaining soldiers likely shot their horses to use as shields for a final stand on the hill. The warriors then closed in and killed every man in Custer's command. Because of this, the Battle of the Little Bighorn is often called "Custer's Last Stand."

Custer's Personal Life

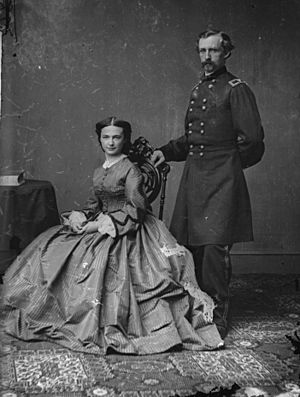

On February 9, 1864, Custer married Elizabeth Clift Bacon (1842–1933). He had first met her when he was ten. They were formally introduced in November 1862. Elizabeth wasn't impressed at first, and her father, Judge Daniel S. Bacon, didn't approve of Custer. But after Custer was promoted to brigadier general, he gained the judge's approval. They married fourteen months after their formal meeting.

Besides "Autie," Custer had other nicknames. During the Civil War, after becoming the youngest brigadier general at 23, the press called him "The Boy General."

Custer loved collecting geological samples and sent them to the University of Michigan. He also bought thoroughbred horses. He took two, Vic and Dandy, on his last campaign. He rode Vic into his last battle. Custer also took his two staghounds, Tuck and Bleuch, leaving them with his orderly before the battle.

Appearance and Habits

Custer was very neat. His wife, Libbie, once wrote that he brushed his teeth after every meal and washed his hands often. He was 5'11" tall and fit. He was an excellent horseman. He could fall asleep quickly and get by on short naps. He often rested on the grass, surrounded by his dogs.

The common image of Custer at the Last Stand, with a buckskin coat and long, curly blonde hair, is not accurate. It was hot, so he and other officers took off their buckskin coats. Also, Custer, whose hair was thinning, had it cut short before leaving Fort Lincoln.

Custer's Death

It is unlikely that any Native American recognized Custer during or after the battle. Many warriors said they didn't know they were fighting Custer or recognize him. Several individuals claimed to have killed Custer, including White Bull and Rain-in-the-Face.

One account from an Oglala named Joseph White Cow Bull suggests he shot a rider wearing a buckskin jacket at the river. This rider was giving orders and was next to someone carrying a flag. When this buckskin-clad rider fell, many attackers stopped. If this rider was Custer, it might explain why his forces broke apart quickly. However, other officers also wore buckskin coats that day.

The bodies of Custer and his brother Tom were wrapped in canvas and blankets. They were buried in a shallow grave. When soldiers returned a year later, animals had disturbed the grave. Only a few small bones were found. Custer was reburied with full military honors at West Point Cemetery on October 10, 1877. The battle site became a National Cemetery in 1886.

Custer's Legacy

Public Image During His Life

Custer was known for being good with public relations. He often invited journalists to join his campaigns. Their positive reports helped his reputation grow. One reporter, Mark Kellogg, died at the Little Bighorn.

Custer enjoyed writing. He wrote many magazine articles about his experiences on the frontier. These were published as a book called My Life on the Plains in 1874. This book is still a valuable source of information about U.S.-Native relations.

After His Death

After his death, Custer became very famous. His wife, Elizabeth, helped his fame grow by publishing several books about him. These books included Boots and Saddles, Life with General Custer in Dakota and Tenting on the Plains.

The deaths of Custer and his troops became the most famous event in the American Indian Wars. This was partly due to a painting commissioned by the Anheuser-Busch brewery. Reprints of this dramatic painting, showing "Custer's Last Stand," were hung in many saloons. This created lasting images of the battle.

President Grant, who had been Custer's superior, criticized Custer's actions at the Little Bighorn. He said Custer's actions caused an "unnecessary" loss of troops. General Phillip Sheridan had a more balanced view of Custer's final military actions. General Nelson Miles praised Custer as a hero who was let down by his officers.

Today, people have different views on Custer's actions during the Indian Wars. Author Evan S. Connell noted that in the 1800s, Custer was seen as a fearless hero. But today, his reputation is often criticized.

Monuments and Memorials

- Counties are named after Custer in six states: Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and South Dakota.

- Townships in Illinois, Michigan, and Minnesota were named for Custer.

- Other towns named after Custer include Custer, Michigan, Custar, Ohio, Custer, South Dakota, Custer City, Oklahoma, and Custer, Wisconsin.

- Custer National Cemetery is located within Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, where Custer died.

- The George Armstrong Custer Equestrian Monument was put up in Monroe, Michigan, Custer's childhood home, in 1910.

- Fort Custer National Military Reservation, near Augusta, Michigan, was built in 1917 for World War I.

- Fort Custer National Cemetery opened officially in 1982.

- Custer Hill is the main troop area at Fort Riley, Kansas. Custer's 1866 home there is now the Custer House Museum.

- The 85th Infantry Division was nicknamed The Custer Division.

- The Black Hills of South Dakota have a county, town, and Custer State Park named after him.

- A mountain peak in the Black Hills also bears his name.

- The Custer house at Fort Abraham Lincoln, near Mandan, North Dakota, has been rebuilt. Annual re-enactments show Custer's 7th Cavalry leaving for the Little Bighorn.

- A monument to Brigadier General Custer was dedicated in 2008 at the 1863 Civil War Battle of Hunterstown site in Pennsylvania.

- The Custer Monument at the United States Military Academy was first shown in 1879. It is now next to his grave.

- The Custer Memorial Monument at his birthplace in New Rumley, Ohio, was built in 1931.

Dates of Rank

| Insignia | Rank | Date | Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | Cadet | 1 July 1857 | United States Military Academy |

| Second Lieutenant | 24 June 1861 | Regular Army | |

| Captain | 5 June 1862 | Temporary aide de camp | |

| First Lieutenant | 17 July 1862 | Regular Army | |

| Brigadier General | 29 June 1863 | Volunteers | |

| Brevet Major | 3 July 1863 | Regular Army | |

| Captain | 8 May 1864 | Regular Army | |

| Brevet Lieutenant Colonel | 11 May 1864 | Regular Army | |

| Brevet Colonel | 19 September 1864 | Regular Army | |

| Brevet Brigadier General | 13 March 1865 | Regular Army | |

| Brevet Major General | 13 March 1865 | Regular Army | |

| Major General | 15 April 1865 | Volunteers (Mustered out on 1 February 1866.) | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | 28 July 1866 | Regular Army |

See also

In Spanish: George Armstrong Custer para niños

In Spanish: George Armstrong Custer para niños

- Custer's Revenge

- Garryowen march song

- German-Americans in the Civil War

- Half Yellow Face

- List of American Civil War generals (Union)

- List of German Americans

- White Swan

Images for kids

-

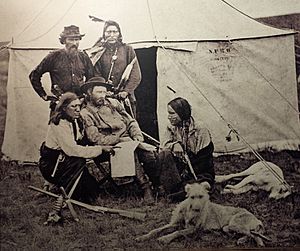

Hunting and camping party near Fort Abraham Lincoln, 1875. An illustration of the variety of uniforms worn by Cavalry Regiments in the west. From left to right: Lt. James Calhoun, Mr. Swett, Capt. Stephen Baker, Boston Custer, Lt. Winfield Scott Edgerly, Miss Watson, Capt. Myles Walter Keogh, Mrs. Maggie Calhoun, Mrs. Elizabeth Custer, Lt. Col. George Custer, Dr. H.O. Paulding, Mrs. Henrietta Smith, Dr. George Edwin Lord, Capt. Thomas Bell Weir, Lt. William Winer Cooke, Lt. R.E. Thompson, Miss ; Wadsworth, another Miss Wadsworth, Capt. Thomas Custer and Lt. Algernon Emery Smith.

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |