Cheyenne facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 22,970 (Northern: 10,840; Southern: 12,130) |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Montana, Oklahoma) | |

| Languages | |

| Cheyenne, English, Plains Sign Talk | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional tribal religion, Native American Church, and Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Arapaho, Blackfoot, Suhtai, and other Algonquian peoples |

The Cheyenne (pronounced shy-AN or shy-EN) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. They are made up of two main Native American tribes: the Só'taeo'o (also called Suhtai) and the Tsétsėhéstȧhese (also called Tsitsistas). These two tribes joined together in the early 1800s.

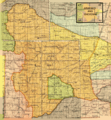

Today, the Cheyenne people live in two federally recognized nations. The Southern Cheyenne are part of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes in Oklahoma. The Northern Cheyenne live on the Northern Cheyenne Tribe of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana. The Cheyenne language is part of the Algonquian language family.

For over 400 years, the Cheyenne way of life changed a lot. They moved from the Great Lakes woodlands to the Northern Plains. By the mid-1800s, the U.S. government moved them onto reservations. When Europeans first met them in the 1500s, the Cheyenne lived in what is now Minnesota. They were close friends with the Arapaho and had ties with the Lakota.

By the early 1700s, other tribes pushed them west across the Missouri River. They settled in North and South Dakota, where they learned to use horses. They brought horse culture to the Lakota people around 1730. The main Cheyenne group, the Tsêhéstáno, once had ten bands. These bands lived across the Great Plains, from southern Colorado to the Black Hills. They often fought their old enemies, the Crow, and later the United States Army.

In the mid-1800s, the Cheyenne bands began to separate. Some stayed near the Black Hills, while others moved closer to the Platte Rivers in central Colorado. With the Arapaho, the Cheyenne pushed the Kiowa to the Southern Plains. Later, the larger Lakota groups pushed the Cheyenne further west.

The Northern Cheyenne are called Notameohmésėhese ("Northern Eaters") or Ohmésėhese ("Eaters") in their language. They live in southeastern Montana on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation. In late 2014, about 10,840 members were counted, with nearly 5,000 living on the reservation. Most of the people on the reservation are Native American. Many still speak the Cheyenne language.

The Southern Cheyenne are known as Heévâhetaneo'o ("Roped People"). They, along with the Southern Arapaho, form the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes in western Oklahoma. In 2008, their combined population was 12,130. About 8,000 of these identified as Cheyenne in 2003.

Contents

- Who Are the Cheyenne People?

- A Journey Through Cheyenne History

- Cheyenne Culture and Traditions

- Notable Cheyenne Leaders

- Cheyenne Population Over Time

- Fun Facts About the Cheyenne

- Images for kids

- See Also

Who Are the Cheyenne People?

The Cheyenne people have a rich history and culture. They are known for their strong traditions and their journey across the American Plains.

What Does "Cheyenne" Mean?

The Cheyenne call themselves Tsétsêhéstâhese, which means "those who are like this" or "our people." The Suhtai tribe, who later joined the Tsétsêhéstâhese, had slightly different ways of speaking and customs.

The name "Cheyenne" comes from the Lakota Sioux word Šahíyena. This word means "little Šahíya." No one is sure who the Šahíya were. Many Plains tribes think it meant the Cree or another group who spoke a language similar to Cree and Cheyenne. Some also believe "Cheyenne" means "red-talker," referring to people who spoke a different language than the Lakota.

Speaking the Cheyenne Language

The Cheyenne people in Montana and Oklahoma speak the Cheyenne language. They call it Tsėhésenėstsestȯtse. About 800 people in Oklahoma speak Cheyenne. There are only a few small differences in words between the two areas. The Cheyenne alphabet has 14 letters. It is one of the larger languages in the Algonquian language group.

Long ago, the Só'taeo'o (Suhtai) bands spoke Só'taéka'ėškóne. This language was so similar to Cheyenne that some people called it a Cheyenne dialect.

A Journey Through Cheyenne History

The Cheyenne people have a long and fascinating history. They adapted to many changes over hundreds of years.

Early Life and Moving West

The first written records of the Cheyenne are from the mid-1600s. At that time, some Cheyenne visited a French fort in what is now Illinois. The Cheyenne lived between the Mississippi River and Mille Lacs Lake in Minnesota. They gathered wild rice and hunted, especially bison, which lived nearby.

According to their stories, the Assiniboine pushed the Cheyenne from the Great Lakes region in the 1600s. The Cheyenne then moved to Minnesota and North Dakota, where they built villages. One important ancient village is Biesterfeldt Village in North Dakota. They reached the Missouri River by 1676.

The Horse Changes Everything

On the Missouri River, the Cheyenne met the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara people. They learned new cultural ways from these neighbors. The Cheyenne were among the first Plains tribes to move into the Black Hills and Powder River Country. Around 1730, they introduced horses to the Lakota bands.

Conflicts with the Lakota and Ojibwe forced the Cheyenne further west. They, in turn, pushed the Kiowa to the south. By 1776, the Lakota had taken over much of the Cheyenne's land near the Black Hills. In 1804, Lewis and Clark visited a Cheyenne village in North Dakota.

Forming Alliances and New Territories

The Cheyenne tribes today come from two related groups: the Tsétsėhéstȧhese and the Só'taeo'o (Suhtai). The Suhtai joined the Tsétshéstȧhese in the mid-1800s. Their oral traditions tell of two special heroes or prophets. These prophets received sacred items from their god, Ma'heo'o.

The Tsétsėhéstȧhese prophet, Motsé'eóeve (Sweet Medicine), received the Maahótse ((Sacred) Arrows Bundle). These arrows were used for tribal wars and kept in a special lodge. Sweet Medicine helped organize Cheyenne society. He set up their military societies, their justice system, and the Council of Forty-four peace chiefs. He also predicted the arrival of horses, cows, and new people to the Cheyenne lands.

The Maahótse (Sacred Arrows) represent male power. The Ésevone / Hóhkėha'e (Sacred Buffalo Hat) represents female power. Together, these two sacred bundles ensure life and blessings for the Cheyenne people.

The Só'taeo'o prophet, Tomȯsévėséhe (Erect Horns), received the Ésevone (Sacred Buffalo Hat Bundle). This happened near the Great Lakes. Erect Horns gave them ceremonies and the Sun Dance. His vision led the tribe to change from farming to a nomadic horse culture. They replaced their earth lodges with portable tipis. Their diet changed from fish and crops to mainly bison and wild plants. Their lands stretched from the upper Missouri River to what is now Wyoming, Montana, Colorado, and South Dakota.

The Ésevone / Hóhkėha'e (Sacred Buffalo Hat) is kept by the Northern Cheyenne. The person who cares for it must be from the Só'taeo'o tribe.

Challenges and Changes on the Plains

After being pushed south and west by the Lakota, the Cheyenne found new lands. Around 1811, the Cheyenne made a strong alliance with the Arapaho people (Hetanevo'eo'o). This friendship lasted for many years. This alliance helped the Cheyenne expand their territory. Their lands reached from southern Montana, through Wyoming, eastern Colorado, and parts of Nebraska and Kansas.

By 1820, American traders met Cheyenne people in what is now Denver, Colorado. The Cheyenne likely hunted and traded in this area much earlier. Some Cheyenne bands moved south for winter. A large part of the tribe moved further south after Bent's Fort was built. The rest stayed near the North Platte and Yellowstone rivers. These groups became the Southern Cheyenne and the Northern Cheyenne. They stayed in close contact.

In the south, the Cheyenne and Arapaho fought with the Comanche, Kiowa, and Plains Apache. Many battles took place. In 1840, these conflicts ended when the tribes formed an alliance. This new alliance allowed the Cheyenne to hunt bison and trade in areas like the Llano Estacado in Texas and New Mexico.

To the north, the Cheyenne allied with the Lakota. This helped them regain some of their old lands around the Black Hills. They avoided the smallpox epidemics of 1837–39 by staying in the Rocky Mountains. However, the cholera epidemic of 1849 greatly affected them. Contact with European-Americans was mostly through traders and explorers.

Important Treaties and Agreements

In the summer of 1825, U.S. officials visited the Cheyenne on the Upper Missouri River. They signed treaties of friendship and trade. These treaties recognized the Cheyenne as living within the United States. They promised peace and agreed to trade only with licensed traders. The Cheyenne also agreed to return stolen goods or pay for them.

The increasing number of settlers traveling along trails like the Oregon Trail in the 1840s caused problems. There was less water and game for Native Americans. This led to the Cheyenne dividing more into Northern and Southern groups.

The cholera epidemic of 1849 spread to the Plains Indians. It caused many deaths among the Cheyenne, with historians estimating about 2,000 people died. This was a huge loss for their population.

Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851

In 1851, a big meeting was held at Fort Laramie. U.S. officials and leaders from many Plains tribes, including the Cheyenne and Arapaho, gathered. The goal was to reduce fighting between tribes. The government "assigned" territories to each tribe and asked them to promise peace.

The treaty also allowed the U.S. government to build roads and forts through Indian lands. In return, the tribes received payments and supplies. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 confirmed Cheyenne and Arapaho territory. This land was between the North Platte River and the Arkansas River.

Conflicts and the Fight for Land

In 1857, the U.S. Army launched an expedition against the Cheyenne. This was in response to incidents along the Platte River. Cheyenne warriors, believing spiritual medicine would protect them, faced the soldiers. However, the soldiers charged with sabers, and the Cheyenne retreated. This was the first battle between the Cheyenne and the U.S. Army.

The Colorado Gold Rush in 1859 brought many European-American settlers onto Cheyenne lands. Travel increased, and conflicts began. In 1861, the Treaty of Fort Wise created a smaller reservation for the Cheyenne in southeastern Colorado. Many Cheyenne did not sign this treaty and continued to live on their traditional hunting grounds.

In 1864, the governor of Colorado Territory, John Evans, and Colonel John Chivington began attacking Indians on the plains. This started the Colorado War.

The Sand Creek Tragedy

On November 29, 1864, the Colorado Militia attacked a peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho camp. This camp, led by Chief Black Kettle, displayed a white flag to show they were friendly. The Sand Creek massacre resulted in the deaths of 150 to 200 Cheyenne, mostly unarmed women and children.

The survivors fled and joined other Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapaho camps. In January 1865, they attacked Camp Rankin in Julesburg in retaliation. They raided the area and killed many European Americans. Most of the Indians then moved north.

Chief Black Kettle still wanted peace. He did not join the raids and returned to the Arkansas River to seek peace with the U.S.

The Battle of Little Bighorn

The Northern Cheyenne fought in the Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876. Along with the Lakota and Arapaho, they defeated General George Armstrong Custer and his soldiers. Historians estimate about 10,000 Native Americans were gathered there. This was one of the largest gatherings in North America before reservations. News of this event caused outrage across the United States.

The Northern Cheyenne's Long Journey Home

After the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the U.S. Army increased efforts to capture the Cheyenne. In 1879, after the Dull Knife Fight, some Cheyenne chiefs like Morning Star (Dull Knife) and Little Wolf surrendered. They expected to live with the Sioux in the north, as promised by a treaty.

However, the U.S. government pressured them to move to the Southern Cheyenne reservation in Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Conditions there were very difficult, with not enough food and illness. On September 9, 1878, a group of Northern Cheyenne, led by Little Wolf and Dull Knife, began their journey back north.

They fought battles with the U.S. Army during their long trek. Dull Knife's group, mostly women, children, and elders, eventually surrendered at Fort Robinson. They were held in barracks without food, water, or heat. Most escaped on January 9, 1879, in freezing weather, but many were recaptured or killed. This event is known as the Fort Robinson tragedy.

Eventually, the U.S. government created a reservation for the Northern Cheyenne in southern Montana.

Life on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation

The Cheyenne who traveled to Fort Keogh (now Miles City, Montana), including Little Wolf, settled near the fort. Many Cheyenne worked as scouts for the army. These scouts helped the Army find Chief Joseph and his Nez Percé band.

The U.S. government established the Tongue River Indian Reservation, now the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation, in 1884. It was later expanded. The Northern Cheyenne were finally allowed to return to their homeland near the Black Hills, which they consider sacred.

Today, the Northern Cheyenne Nation is one of the few American Indian nations that controls most of its land. They have also managed to keep their culture, religion, and language strong.

Cheyenne Culture and Traditions

The Cheyenne people have a rich culture that has adapted over centuries.

Cheyenne Government and Bands

The traditional Cheyenne government is a unified system. The main traditional government is the Arrow Keeper, followed by the Council of Forty-four. Early in their history, three related tribes joined to form the Tsétsėhéstȧhese, or "Like Hearted People," known today as the Cheyenne.

The unified tribe then divided into ten main bands:

- Hevéškėsenėhpȧho'hese

- Hévhaitanio

- Masikota

- Omísis

- Só'taeo'o (Northern and Southern)

- Wotápio

- Oivimána (Northern and Southern)

- Hisíometanio

- Ohktounna

- Hónowa

Each of these ten bands had four chiefs who were delegates to the council. Four other chiefs served as main advisors. This system also guided the Cheyenne military societies, which planned warfare, enforced rules, and conducted ceremonies.

The Importance of Horses

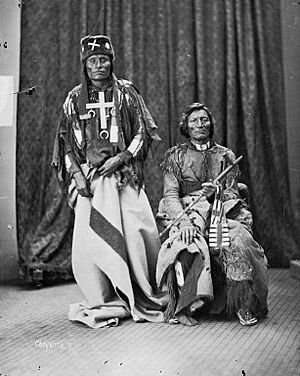

As a horse and warrior people on the Plains, Cheyenne men hunted and sometimes fought with other tribes. Warriors were seen as protectors, providers, and leaders. They earned respect by showing bravery in battle.

Cheyenne women tanned hides for clothing and shelter. They also gathered roots, berries, and other plants. From these resources, women made lodges, clothing, and other important items. Their lives were very active and required a lot of physical effort.

Role Models in Cheyenne Society

A Cheyenne woman gains respect if she comes from a family with honored ancestors. She is also valued for being friendly and getting along with her female relatives. Cheyenne women are expected to be hardworking, modest, skilled in traditional crafts, and knowledgeable about Cheyenne culture and history. Speaking the Cheyenne language fluently is also highly valued.

Notable Cheyenne Leaders

- George Bent (1843–1918), a warrior, interpreter, and Cheyenne historian.

- Black Kettle (c. 1803–1868), a Southern Cheyenne chief who sought peace.

- Morning Star (1810–1883), also known as Dull Knife, a head chief of the Northern Cheyenne.

- Little Wolf (ca. 1820–1904), a Northern Só'taeo'o chief and Sweet Medicine Chief, known for leading his people north.

- St. David Pendleton Oakerhater (1847–1931), a Southern Cheyenne veteran, artist, and deacon.

- Owl Woman (d. 1847), daughter of White Thunder and wife of William Bent.

- Roman Nose (in Cheyenne: Vóo'xénéhe), a legendary Northern Cheyenne war hero.

- Two Moons, a Northern Cheyenne Chief who fought at Little Bighorn.

- Wooden Leg, a Northern Cheyenne warrior who fought at Little Bighorn.

- Wolf Robe, a Southern Cheyenne chief known as a peacemaker.

Cheyenne Population Over Time

In 1856, estimates placed the Cheyenne population at around 10,000 people. By 1875, about 4,228 people were reported. In 1900, the count was 3,446 (2,037 Southern Cheyenne and 1,409 Northern Cheyenne). The population was 3,055 in 1910 and 3,281 in 1921.

The Cheyenne population has grown significantly in recent times. The U.S. census of 2020 counted 22,979 Cheyenne people.

Fun Facts About the Cheyenne

- In Cheyenne culture, jobs were given based on age and whether you were a boy or a girl.

- They usually built their villages near rivers. This made it easier for them to trade with others.

- The Cheyenne believed the world had seven main levels.

- The Cheyenne bands would meet for four days each spring for the Sun Dance ceremony.

- Kids enjoyed playing hoop games and lacrosse.

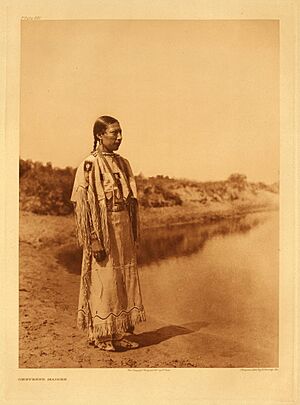

- Cheyenne women wore long deerskin dresses. Men wore breechcloths (a long piece of buckskin that went between the legs and looped over a belt) with leather leggings.

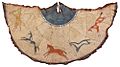

- Cheyenne artists are known for their beautiful quillwork, native beading, pottery, and pipestone carving.

- The Dog Soldiers were the most famous of the Cheyenne warrior societies.

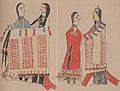

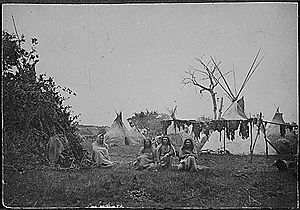

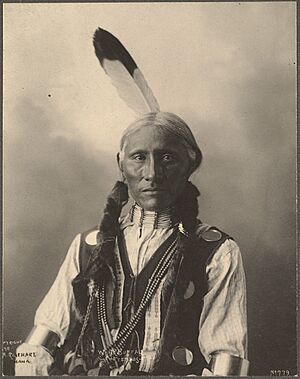

Images for kids

-

Cheyenne hide dress, c. 1920, Gilcrease Museum

-

Cheyenne beaded hide shirt, Woolaroc

-

W. Richard West Jr., former director and co-founder of the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian

-

Portrait of Cheyenne chief Wolf-on-the-Hill by George Catlin, 1832. A band of Cheyenne visited Fort Pierre, South Dakota in 1832 where some were painted by Catlin during a westward expedition.

See Also

In Spanish: Cheyenes para niños

In Spanish: Cheyenes para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |