Colorado War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Colorado War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars, Sioux Wars | |||||||

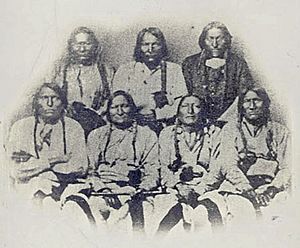

A delegation of Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Arapaho chiefs at Denver, Colorado on September 28, 1864. Black Kettle is second from left in the front row. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Cheyenne Arapaho Sioux |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

William O. Collins |

Black Kettle Roman Nose Spotted Tail Pawnee Killer |

||||||

The Colorado War was a conflict that took place in 1864 and 1865. It was fought between the Southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, and some Sioux (Lakota) tribes against the U.S. army, Colorado militia, and white settlers. This war happened in the Colorado Territory and nearby areas.

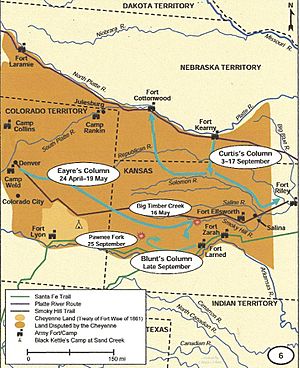

The Kiowa and Comanche tribes were involved in some smaller fights in the southern part of the territory. However, the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux were the main groups fighting north of the Arkansas River. They fought along the South Platte River and near important travel routes like the Great Platte River Road and the Overland Trail. The U.S. government and Colorado authorities used the 1st Colorado Cavalry Regiment, also known as the Colorado Volunteers, in this war. The main fighting happened on the Colorado Eastern Plains, stretching into Kansas and Nebraska.

A very sad event during this war was the Sand Creek massacre in November 1864. U.S. soldiers attacked the winter camp of Southern Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle. At first, this attack was called a big victory. But later, people strongly criticized it as a terrible act of violence. This massacre led to military and government investigations. These investigations found that John M. Chivington, the commander of the Colorado Volunteers, and his troops were responsible.

After the Sand Creek Massacre, the Native American tribes moved north. They wanted to join their relatives, the Northern Cheyenne, Northern Arapaho, and the main Sioux groups in Wyoming. On their way, they carried out many raids along the South Platte River. They also attacked U.S. military forts and forces. They managed to avoid being defeated or captured by the U.S. army.

Contents

Why the War Started

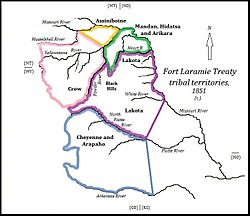

In 1851, the United States and several tribes, including the Cheyenne and Arapaho, signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie. This treaty described the land where the Cheyenne and Arapaho lived. It stretched from the North Platte River in what is now Wyoming and Nebraska down to the Arkansas River in present-day Colorado and Kansas. The treaty also said that these were the minimum lands for the tribes. It didn't stop them from having other lands not mentioned.

At first, this land was not very interesting to white settlers. People even called it "the Great American Desert." But in November 1858, gold was found in the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. This started a gold rush. Many white settlers began to move across Cheyenne and Arapaho lands. Officials in the Colorado Territory then pushed the government to reduce the size of the Native American treaty lands.

On February 18, 1861, some Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs signed a new agreement called the Treaty of Fort Wise. They signed it at Bent's New Fort in Colorado. With this treaty, they gave up more than 90 percent of the land they had been given by the Fort Laramie Treaty. Their new, much smaller land was in eastern Colorado.

However, some Cheyenne, like the Dog Soldiers, did not agree with this new treaty. The Dog Soldiers were a strong group of Cheyenne and Lakotas. They refused to follow the new rules. They kept living and hunting in the lands of eastern Colorado and western Kansas, which had many bison. They became more upset as more white settlers moved onto their lands. The Cheyenne who opposed the treaty said that only a few chiefs had signed it. They also said these chiefs didn't have permission from the rest of the tribe. They claimed the chiefs didn't understand what they were signing. They also believed the chiefs were bribed with many gifts. But the white settlers said the treaty was a "solemn agreement." They thought any Native Americans who didn't follow it were hostile and planning a war.

First Fights Break Out

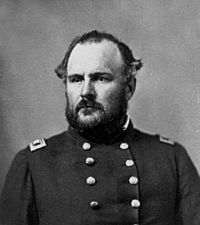

In March 1864, it didn't seem like a war was about to start in Colorado. The U.S. army was even planning to move many of its soldiers away from the Great Plains. They wanted to send them to fight in the Civil War. But on April 9, Colonel John Chivington, who led the Colorado volunteers, reported that Native Americans had stolen 175 cattle from white settlers. The Cheyenne later said they found the cattle wandering freely and took them to their camps.

Lt. George Eayre and his soldiers were sent to get the cattle back. On April 12, Eayre met a group of Cheyenne. A fight started, and one soldier was killed. Eayre burned 70 tipis in a nearby camp. He then returned to Denver with 20 cattle. This fight happened near the Republican River.

Around the same time, a group of fourteen Dog Soldiers met some soldiers north of the South Platte River. The soldiers told the Dog Soldiers to drop their weapons. The soldiers thought the Dog Soldiers had stolen four mules from a white owner. A fight began, and two soldiers were killed. Three Dog Soldiers were wounded. George Bent, a Cheyenne warrior who was part white, said the Native Americans were confused. They thought these attacks by soldiers came out of nowhere. Bent thought that Colonel Chivington and the Colorado Volunteers might have caused these fights. He believed they wanted to stay in Colorado to fight Native Americans instead of going to Kansas to fight in the Civil War.

The Conflict Grows

Small fights kept happening, started by both Native Americans and U.S. soldiers. In May, Lt. Eayre was out again with 100 men and two small cannons. Near the Smoky Hill River in Kansas, Eayre had a battle with the Dog Soldiers. He said the Native Americans started the fight. But the Native Americans said the soldiers attacked them. Eayre claimed he killed 28 Native Americans and lost four of his own men. Bent said only three Native Americans were killed. One of them was Lean Bear, an important Dog Soldier leader. Eayre finished his raid at Fort Larned. There, 240 of his horses and mules were stolen by the Kiowa. Arapahoes offered to help get the horses back, but soldiers shot at them. After that, the Arapahoes became hostile.

Also in May, Major Jacob Downing and Colorado volunteers attacked a Cheyenne village. This happened in Cedar Canyon, north of the South Platte River. The people in the village were mostly older women and children. Downing reported killing 26 Native Americans. One soldier was killed. On June 11, only 50 kilometers (31 miles) from Denver, four Arapaho killed four members of the Hungate family. This made people in Denver very scared that the war was right on their doorstep. On July 12, a group of Miniconjou Sioux attacked a wagon train on the Oregon Trail. They killed four men. Soldiers chased the attackers but were ambushed. One soldier was killed. On August 20, Native Americans killed five members of a family in Nebraska. A total of 51 people were reported killed by Native Americans along the Little Blue River in Kansas and Nebraska. The roads to Denver across the Great Plains were closed from August 15 to September 24.

Soldiers from Kansas also joined the war. On September 25, Major General James G. Blunt and 400 soldiers met Cheyennes. They were near the Pawnee Fork of the Arkansas River. Blunt claimed to have killed nine Native Americans. He lost two soldiers.

Hopes for Peace

In July 1864, Colorado Governor John Evans sent a message to the Plains Indians. He invited friendly tribes to go to a safe place at Fort Lyon. This fort was on the eastern plains, near what is now Lamar, Colorado. There, the U.S. troops would give them food and protection. Many Native Americans wanted peace, but the Dog Soldiers still wanted to fight.

On August 29, 1864, two Cheyenne men who were part white, George Bent and Edmund Guerrier, wrote letters. They wrote on behalf of "Black Kettle and Other Chiefs." They offered to make peace and return seven white prisoners. In exchange, they wanted Native American prisoners held by the whites to be returned. In response, Major Edward W. Wynkoop, the commander of Fort Lyon, led 130 men to try and get the prisoners back. They met a group of 600 or more Cheyenne warriors on the Smoky Hill River. Wynkoop talked with Black Kettle and other chiefs. He invited the chiefs to visit Denver to meet with Governor Evans and Colonel Chivington. The meetings happened at Camp Weld. Black Kettle and the other chiefs seemed to believe they had made peace with the white settlers.

When they returned to Fort Lyon, Wynkoop promised protection to the peaceful Native Americans. He told them to set up a village on Sand Creek, 60 kilometers (37 miles) northeast of Fort Lyon. This area was within the land given to the Cheyenne and Arapaho by the Treaty of Fort Wise. Black Kettle and his followers moved to Sand Creek. However, on October 17, Chivington removed Wynkoop from his command. This seemed to be because Wynkoop supported a peaceful end to the war.

Even though Black Kettle and others wanted peace, the Dog Soldiers and other hostile Native Americans continued to raid ranches and wagon trains. They also clashed with soldiers during the fall, especially in Kansas and Nebraska. Several attacks by the U.S. army did not work well.

The Sand Creek Attack

On November 29, 1864, 675 men, mostly from the Colorado Volunteers, led by Colonel John M. Chivington, entered Cheyenne and Arapaho land. This land was given to the Cheyenne and Arapaho by the Treaty of Fort Wise. The soldiers attacked the village of Black Kettle. An American flag and a white flag of truce were flying over the village. The soldiers killed about 150 Native Americans. There were no Dog Soldiers or other hostile Native Americans in the village when Chivington attacked.

Native American Response

After the Sand Creek massacre, according to George Bent, the Cheyenne, Northern Arapaho, and the Brulé and Oglala Sioux met. This meeting happened around January 1, 1865, on Cherry Creek in what is now Cheyenne County, Kansas. They agreed to go to war with the white settlers. They decided to attack Camp Rankin and the nearby town of Julesburg, Colorado. The Sioux were the first to agree to war. They had the honor of leading a group of possibly 1,000 warriors and 3,000 women and children. After attacking Julesburg, the Native Americans planned to march north to join their relatives in Wyoming.

Julesburg had a stagecoach station, stables, a telegraph office, a warehouse, and a large store. It served travelers going to Denver along the South Platte. About 50 armed men lived there. One mile west was Camp Rankin, with about 60 cavalry soldiers. Both places were surrounded by high sod walls. On January 7, 1,000 warriors attacked Julesburg and Camp Rankin. They killed 14 soldiers and four armed civilians. The Native Americans had very few or no losses themselves. The surviving soldiers and civilians hid inside Camp Rankin. The Native Americans then took everything valuable from the town.

Not all the Native Americans wanted to continue the war. After the raid, Black Kettle and about 80 families (perhaps 100 men and their families) left the main group. They joined the Kiowa and Comanche south of the Arkansas River. Many Southern Arapaho also moved south of the Arkansas.

From January 28 to February 2, the Native Americans carried out a big raid. They went along the valley of the South Platte River. The Cheyenne raided west of Julesburg, the Northern Arapaho near Julesburg, and the Sioux east of Julesburg. They destroyed many ranches and stagecoach stations along 150 kilometers (93 miles) of the river valley. They also gathered a large herd of captured cattle. Near Valley Station (today Sterling, Colorado), the Cheyenne had a small fight with soldiers. Lt. J. J. Kennedy said his force fought the raiders and killed 10 to 20 Native Americans. He also said they got back 400 stolen cattle. George Bent said it was a minor skirmish. He said no Native Americans were killed or wounded. He also said the only cattle the soldiers got back were those the Native Americans had left behind because they were too weak to steal. During the raid, the Cheyenne met a group of nine former soldiers. They killed all nine of them. Soldiers and ranchers claimed to have caused many deaths among the raiders. But Bent said he only knew of four Native Americans who were killed during the raids. Three were Sioux and one was an Arapaho.

On February 2, the Native Americans left their large camp on the South Platte River. They continued north toward the Powder River country of Wyoming. They wanted to join their relatives there. The Sioux led the way because they knew the area best. On their journey, the Native Americans had two more small fights in Nebraska. These were at Mud Springs and Rush Creek. In the months that followed, the Native Americans often raided wagon trains and military places along the Oregon Trail in Wyoming. In the summer of 1865, the Native Americans launched a large attack in the Battle of Platte Bridge (today Casper, Wyoming). They won a small victory there. Later that summer, the U.S. army entered Native American territory in Wyoming. More than 2,000 soldiers were part of the Powder River Expedition, but it didn't work very well.

What Happened Next

Historian John D. McDermott said that the Colorado War was the last time the Northern and Southern Cheyennes and Arapahos and the Brulé Sioux worked together. They effectively resisted the many white settlers and soldiers moving through and settling on their lands. After this war, the Sioux and their allies would not attack in the same way again. Future battles between Native Americans and white settlers would be more about defending their homes. They would not be about punishing those who had wronged them, as the reaction to the Sand Creek massacre was meant to be.

By December 1865, the Colorado War slowly ended. Most of the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho who had gone north to Wyoming returned to the southern Great Plains. The Brulé Sioux, led by Spotted Tail, who had been allies of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, settled peacefully near Fort Laramie. Black Kettle, who always wanted peace, signed the Little Arkansas Treaty in October 1865. This treaty required his group of Southern Cheyenne to move to Indian Territory (which is now Oklahoma). Roman Nose and the Dog Soldiers continued to be hostile. They kept raiding and fighting the U.S. army in Kansas and Colorado.

The two Cheyenne men who were part white, George Bent and Edmund Guerrier, also returned to the southern plains. Bent became a translator between the Cheyenne and the white settlers. He also became a historian of the Colorado War and the Cheyenne through letters he wrote to scholar George E. Hyde. Guerrier worked for a time as a scout for George Armstrong Custer. He helped Custer in campaigns against his Cheyenne relatives. He also worked as a translator for many meetings between the tribe and the United States. Guerrier married Julia Bent, who was George Bent's sister and also survived the Sand Creek massacre.

Looking Into the Attack

In 1865, a group called the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War investigated the Sand Creek massacre. They concluded that Colonel Chivington surprised and killed people at Sand Creek. These people "had every reason to believe they were under the protection of the United States authorities." The committee also said Chivington then returned to Denver and bragged about what he and his men had done.

Another group from Congress, the Joint Special Committee on Conditions of Indian Tribes, also investigated the Sand Creek massacre in 1865. This was part of a bigger look at U.S.-Native American issues across the country. One of their main findings was that ongoing conflicts with Native Americans were directly caused by the actions of "lawless white men." A group of lawmakers from this committee visited Fort Lyon in 1865. They told the tribe members there that the government did not approve of Chivington's actions.

Chivington had already left his military job, so he was not put on trial for the massacre. After Sand Creek, Chivington moved often and was involved in several problems. He defended his actions at Sand Creek until he died in 1894. The Methodist Church, where he was a lay preacher, apologized for his actions in 1996. A street named after him in Longmont, Colorado was renamed in 2005.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |