Kiowa facts for kids

Three Kiowa men in 1898

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 12,000 (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Kiowa, Plains Sign Talk | |

| Religion | |

| Native American Church, traditional tribal religion, Sun Dance, Christianity |

The Kiowa people are a Native American tribe. They are one of the Indigenous people of the Great Plains in the United States. Long ago, they moved south from western Montana to the Rocky Mountains in Colorado during the 1600s and 1700s. By the early 1800s, they had settled in the Southern Plains. In 1867, the Kiowa were moved to a special area called a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma.

Today, the Kiowa are officially recognized by the US government as the Kiowa Indian Tribe of Oklahoma. Their main office is in Carnegie, Oklahoma. In 2011, there were about 12,000 members of the tribe. The Kiowa language (Cáuijògà) is part of the Tanoan language family. Sadly, it is in danger of disappearing, with only about 20 people speaking it in 2012.

Contents

What's in a Name?

| Person | Cáui |

|---|---|

| People | Cáuigú |

| Language | Cáuijògà |

| Country | Cáuidàumgà |

In their own language, the Kiowa call themselves Cáuigú, which means "Principal People." The first part of the name, Cáui-, simply means 'Kiowa'. We don't know exactly where this part of the name came from. The second part, -gú, means 'people' or 'plural'.

In the past, the tribe had other names. One was Kútjàu, meaning "emerging" or "coming out rapidly." Another was Tep-da. These names relate to an old story about how the tribe came from a hollow log. Later, they called themselves Kom-pa-bianta, which means "people with large tipi flaps." This was before they met other tribes from the Southern Plains or European settlers.

In English, Kiowa is usually said as KI-o-wa (like KAI-oh-wah). The English name comes from how the Comanches would say Cáuigú.

In Plains Indian Sign Language, the sign for Kiowa involves holding two straight fingers near the right eye and moving them back past the ear. This sign comes from an old Kiowa hairstyle. They used to cut their hair horizontally from their eyes to their ears. This helped keep their hair out of the way when they shot arrows. The artist George Catlin painted Kiowa warriors with this special hairstyle.

Kiowa Language and Communication

The Kiowa language is part of the Kiowa-Tanoan language family. This connection was first suggested in 1910 and later confirmed in 1967. Parker McKenzie, born in 1897, was a very important expert on the Kiowa language. He learned English only when he started school. He worked with linguists to study and record the language. His letters about Kiowa pronunciation and grammar are kept in the National Anthropological Archives.

The Kiowa language is mainly spoken by Kiowa people in Caddo, Kiowa, and Comanche counties in Oklahoma.

Besides their own language, the Kiowa also used Plains Sign Talk. This was a common way for many different Native American nations across North America to communicate, especially for trading. It became a language on its own.

How the Kiowa Tribe is Governed

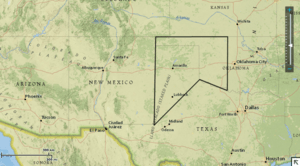

The Kiowa Indian Tribe of Oklahoma has its main office in Carnegie, Oklahoma. Their tribal area covers several counties in Oklahoma, including Caddo, Comanche, and Kiowa counties. To be a member of the tribe, a person needs to have at least one-quarter Kiowa heritage.

As of 2022, the leader of the Kiowa Tribe is Chairman Lawrence SpottedBird. The Vice-Chairman is Jacob Tsotigh.

Kiowa Economic Activities

The Kiowa tribe creates its own special vehicle tags. In 2011, the tribe owned a smoke shop and several restaurants. These included the Morningstar Steakhouse and Grill, Morningstar Buffet, and The Winner's Circle restaurant in Devol, Oklahoma. They also owned Kiowa Bingo near Carnegie, Oklahoma.

The tribe also owns three casinos. These are the Kiowa Casino in Carnegie, another in Verden, and the Kiowa Casino and Hotel Red River in Devol.

Kiowa Culture and Daily Life

The Kiowa originally came from the Northern Plains and later moved to the Southern Plains. Their society values family connections from both the mother's and father's sides. They don't have clans, but they have a complex system based on family ties. They also have groups based on age and gender.

Homes and Travel

The main type of home for the Kiowa was the tipi. Tipis were cone-shaped lodges made from bison hides sewn together. Long wooden poles, about 12 to 25 feet long, supported the tipi. These poles came from red juniper and lodgepole pine trees. Tipis had at least one entrance flap. There were also smoke flaps at the top to let smoke out from the fire pit inside. The floor of the tipi was covered with animal furs and skins to make it warm and comfortable. Tipis were designed to be warm in winter and cool in summer. They were easy to take down and set up quickly, which was perfect for a tribe that moved often. When traveling, the tipi poles were used to build a travois. Special paintings often decorated the outside and inside of tipis, with each design having a unique meaning.

Before horses arrived in North America, the Kiowa used dogs to carry and pull their belongings. Tipis, goods, and even small children were carried on travois. A travois was a frame made from tipi poles, pulled by dogs.

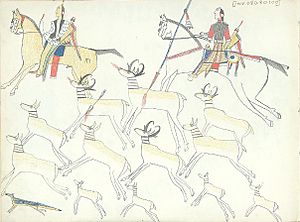

The arrival of horses changed the Kiowa way of life completely. They got horses by trading or by taking them from Spanish ranches in Mexico and from other Native American tribes. With horses, they could carry more things, hunt more animals over a wider area, and travel much farther and faster. The Kiowa became very skilled warriors on horseback. They would travel long distances to raid their enemies. The Kiowa were known as some of the best horse riders on the Plains. A man's wealth was often measured by how many horses he owned. Some wealthy individuals had hundreds of horses. Stealing horses from enemies was considered a great honor for young warriors. Kiowa horses were often painted by the medicine man for good luck and protection in battle. They were also decorated with beaded masks and feathers in their manes. Mules and donkeys were also used for travel and were seen as valuable, but not as much as horses.

Kiowa Food and Hunting

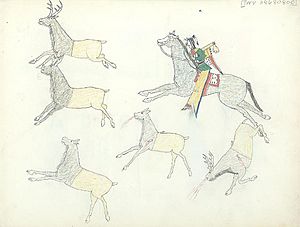

The Kiowa were historically a nomadic people, meaning they moved from place to place to hunt and gather food. Their diet was similar to other Plains tribes, like the Comanche. The most important food source for the Kiowa was the American bison, also known as buffalo. Before horses, bison were hunted on foot. Hunters had to get very close to shoot them with arrows or use long spears. Sometimes, they would wear wolf or coyote skins to sneak up on the bison herds.

Hunting bison became much easier after the Kiowa got horses. Men hunted bison on horseback using bows and arrows or long spears. Kiowa women prepared bison meat in many ways: roasted, boiled, and dried. Dried meat was made into pemmican, which was a very important food for long journeys. Pemmican was made by grinding dried lean meat into a powder. Then, it was mixed with melted fat and sometimes berries. This mixture was shaped into bars and stored in pouches. Sometimes, certain parts of the bison were eaten raw.

Other animals hunted included deer, elk, pronghorn, wild mustangs, wild turkey, and bears. When game was scarce, the Kiowa would eat smaller animals like lizards, waterfowl, skunks, snakes, and armadillos. They also raided ranches for Longhorn cattle and horses when food was hard to find.

Men did most of the hunting. Women were responsible for gathering wild plants like berries, roots, seeds, nuts, and wild fruits. However, women could also hunt if they chose to. Important plants in the Kiowa diet included pecans, prickly pear, mulberries, persimmons, acorns, plums, and wild onions. They also got cultivated crops like squash, maize (corn), and pumpkin by trading with or raiding other tribes, such as the Pawnee. Before they had metal pots from Europeans, Kiowa cooks boiled meat and vegetables by lining a pit in the ground with animal hides. They would fill the pit with water and then add hot rocks from a fire to cook the food.

Social Structure and Leadership

The Kiowa had a well-organized tribal government. They held a yearly Sun Dance gathering. They also had an elected head-chief who was a symbolic leader for the entire nation. Warrior societies and religious societies were very important in Kiowa society, each with specific roles. Chiefs were chosen based on their bravery in battle, intelligence, generosity, experience, and kindness. The Kiowa admired young, fearless warriors, and their whole tribe was structured around this ideal.

Women gained respect through the achievements of their husbands, sons, and fathers. They also gained prestige through their own artistic skills. Kiowa women tanned hides, sewed skins, painted geometric designs on rawhide bags (parfleche), and later created beautiful beadwork. They took care of the camp when the men were away. They gathered and prepared food for winter and took part in important ceremonies. Kiowa men often lived with their wives' extended families.

The Kiowa had different groups within the tribe. Local groups were led by a leader, and these groups would join together to form larger bands. These bands were led by a chief.

The Kiowa also had two main political divisions, especially in how they related to the Comanche tribe:

- Northerners (Thóqàhyòp): These Kiowa lived along the Arkansas River and the Kansas border. They were known as the "Men of the Cold" and were the larger group.

- Southerners (Sálqáhyóp): These Kiowa lived in the Llano Estacado (Staked Plains) and the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas. They were called the "Hot People" and were allies of the Comanche.

Later, as more settlers moved onto Kiowa lands, a new group appeared:

- The Wild Mustang Kiowa (Gúhàlēcáuigú): They were named after the large herds of wild mustangs in the area where they lived. They were very close to a Comanche band known as the "Wild Mustang People."

After the death of their high chief Dohäsan in 1866, the Kiowa split into two groups: one that wanted peace and one that wanted to continue fighting. These groups formed based on how close they were to Fort Sill and how much they interacted with the US Army.

During the annual Sun Dance (called Kc-to), different Kiowa bands had special duties:

- The Kâtá band was the largest and most powerful. They were responsible for providing enough bison meat and other food for the Sun Dance. Famous chiefs like Dohäsan and Guipago belonged to this band.

- The Kogui band was in charge of leading the war ceremonies during the Sun Dance. Many famous warriors came from this band, like Satanta (White Bear) and Kicking Bird.

- The Kaigwa band were the guardians of the Sacred or Medicine bundle (Tai-mé) and the holy lance. Because of this, they were highly respected.

- The Kinep or Khe-ate band were often called "Sun Dance Shields." They acted as police during the dance, making sure everyone was safe.

- The Semat band, who were allies (the Kiowa Apache), could participate equally but had no specific duties during the Sun Dance.

- The Soy-hay-talpupé band was the smallest Kiowa band.

Enemies and Warrior Culture

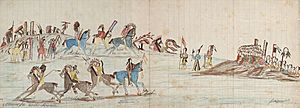

Like most Plains Indians during the time of horse culture, the Kiowa were a warrior people. They often fought with enemies both near and far. The Kiowa were known for their long-distance raids, which went as far south as Mexico and north into the Northern Plains. Almost all fighting happened while riding horses.

Enemies of the Kiowa included the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Navajo, Ute, and sometimes Lakota to the north and west. To the east, they fought with the Pawnee, Osage, Kickapoo, Kaw, Caddo, Wichita, and Sac and Fox. To the south, they fought with the Lipan Apache, Mescalero Apache, Chiricahua Apache, and Tonkawa. The Kiowa also had conflicts with Native American nations who were forced to move to Indian Territory from the Southeastern and Northeastern United States, such as the Cherokee, Choctaw, Muskogee, and Chickasaw.

Later, the Cheyenne and Arapaho made peace with the Kiowa. Together, they formed a strong alliance with the Comanche and the Plains Apache. They fought against white settlers and US soldiers, as well as Mexicans and the Mexican Army.

Like other Plains Indians, the Kiowa had specific warrior societies. Young men who showed bravery and skill in battle were often invited to join one of these societies. Besides fighting, these groups also helped keep peace within the camps and the tribe. There were six warrior societies among the Kiowa:

- The Po-Lanh-Yope (Little Rabbits) was for boys. All young Kiowa boys joined this group, which focused on social activities and education, not violence.

- The Adle-Tdow-Yope (Young Sheep), Tsain-Tanmo (Horse Headdresses), Tdien-Pei-Gah (Gourd Society), and Ton-Kon-Gah (Black Legs or Leggings) were societies for adult warriors.

- The Koitsenko (Principal Dogs or Real Dogs) was the most elite group. It had only ten of the best warriors from all the Kiowa. Members were chosen by the other adult warrior societies.

Kiowa warriors used both traditional and new weapons. These included long spears, bows and arrows, tomahawks, knives, and war clubs. Later, they also used rifles, shotguns, revolvers, and cavalry swords. Shields were made from tough bison hide stretched over a wooden frame, or from a bison skull, making them small and strong. Shields and weapons were decorated with feathers, furs, and animal parts like eagle claws for ceremonies.

Kiowa Calendars and History Records

The Kiowa people told ethnologist James Mooney that the first person to keep a calendar in their tribe was Little Bluff, or Tohausan. He was the main chief of the tribe from 1833 to 1866. Mooney also worked with two other calendar keepers, Settan (Little Bear) and Ankopaaingyadete (Anko). Other Plains tribes also kept picture records, known as "winter counts."

The Kiowa calendar system is special because they recorded two events for each year. This gave them a more detailed record of their history. Silver Horn (1860–1940), or Haungooah, was a highly respected Kiowa artist. He also kept a calendar and was a religious leader later in his life.

Funeral Traditions

In Kiowa tradition, death was strongly linked to dark spirits and negative forces. The death of a person was seen as a very difficult experience. The fear of ghosts came from the belief that spirits often didn't want to leave their physical life. People thought spirits stayed around the body or burial place, and might haunt old homes and belongings. Lingering spirits were also believed to help the dying move from the physical world to the afterlife. Because of these fears, the community's reactions to death were immediate and strong. Families and relatives were expected to show their sadness by wailing, tearing their clothes, and shaving their heads. There are also stories of people cutting themselves or cutting off finger joints as a sign of grief. Women and widowed spouses were expected to show their mourning more openly.

The body of the person who died had to be washed before burial. The person who did the washing, usually a woman, also combed the hair and painted the face of the dead. The burial happened quickly, usually on the same day, unless the death happened at night. A quick burial was believed to reduce the chance of spirits staying around the burial site. After the burial, most of the dead person's belongings and their tipi were burned. If they shared a tipi or house with family, the surviving relatives would move to a new home.

Kiowa History

The Kiowa language is part of the Kiowa-Tanoan language family. This suggests that the Kiowa might have shared an origin with other Native American nations in this language family, like the Tiwa and Tewa. However, in historical times, the Kiowa lived as hunter-gatherers, unlike the settled village societies of the other groups. The Kiowa also had a rich ceremonial life and developed their "Winter counts" as calendars. The Kiowa say their origins are near the Missouri River and the Black Hills. They know they were pushed south by pressure from the Sioux tribe.

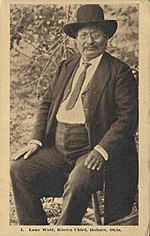

Important Kiowa leaders included Dohäsan (Little Mountain), who was a great chief from 1833 to 1866. He united the Kiowa and signed treaties with the United States. Other famous leaders were Satank (Sitting Bear), Guipago (Lone Wolf The Elder), Satanta (White Bear), and Kicking Bird.

Dohasan is often seen as the greatest Kiowa Chief because he led the tribe for 30 years. He signed several treaties with the United States. When Dohasan died, he named Guipago as his successor. Guipago and Satanta, along with Satank, led the group of Kiowa who wanted to fight. Kicking Bird and Napawat led the group who wanted peace.

In 1871, Satank, Satanta, and Big Tree helped lead the Warren Wagon Train Raid. They were arrested by US soldiers. On the way to Texas, Satank was shot while trying to escape. Satanta and Big Tree were later imprisoned.

In September 1872, Guipago met with Satanta and Big Tree. Guipago had said he would only go to Washington to meet President Grant for peace talks if his friends were released. Guipago eventually got them freed in September 1873. Guipago, Satanta, and other Kiowa warriors led fights during the "Buffalo War" in 1874. They surrendered after the Palo Duro Canyon fight. Satanta later took his own life in prison in 1878. Guipago died in 1879 after getting sick in jail.

The sculptor of the Indian Head nickel, James Earle Fraser, said that Chief Big Tree was one of his models for the US coin.

Early History and Moving South

The Kiowa became a distinct people in their original homeland near the northern Missouri River Basin. They were looking for more land, so they traveled southeast to the Black Hills in present-day South Dakota and Wyoming around 1650. In the Black Hills, the Kiowa lived peacefully with the Crow Indians. They had a long-standing friendship with the Crow. At this time, the Kiowa were organized into 10 bands and had about 3,000 people.

Later, pressure from the Ojibwe tribe in the north pushed the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and then the Sioux westward into Kiowa territory around the Black Hills. The Kiowa were then pushed south by the Cheyenne, who were themselves pushed out of the Black Hills by the Sioux. In their early history, the Kiowa used dogs to pull their belongings. Later, they got horses through trade and raids with the Spanish and other Native American nations in the Southwest.

Eventually, the Kiowa shared a large territory called Comancheria with the Comanche tribe. This land was in western Kansas, eastern Colorado, most of Oklahoma, and parts of Texas and New Mexico. The close friendship between the Kiowa and Comanche began in 1790. They made an alliance to share hunting grounds and protect each other. From then on, the Comanche and Kiowa hunted, traveled, and fought wars together. The Kiowa also formed a very close alliance with the Plains Apache (Kiowa-Apache). These two nations shared much of their culture and took part in each other's annual meetings. This strong alliance of Southern Plains nations prevented the Spanish from gaining strong control over the Southern Plains.

Conflicts and Changes

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, the Kiowa had little to fear from European neighbors. The Kiowa and Comanche controlled a vast area from the Arkansas River to the Brazos River. The enemies of the Kiowa were usually the same as the enemies of the Comanche. To the east, they fought with the Osage and Pawnee.

In the early 1800s, the Cheyenne and Arapaho began camping on the Arkansas River, leading to new conflicts. To the south, the Kiowa and Comanche were friendly with Caddoan-speaking tribes. The Comanche were at war with the Apache of the Rio Grande region.

The Kiowa fought with the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Pawnee, Sac and Fox, and Osages. In 1833, the Osage attacked a Kiowa camp, causing many deaths. During this attack, the Osage captured the sacred Tai-me, which was important for the Kiowa Sun Dance. The Kiowa could not perform the Sun Dance until the Tai-me was returned in 1835.

The Kiowa traded with the Wichita to the south and with the Mescalero Apache and New Mexicans to the southwest. After 1840, the Kiowa and their former enemies, the Cheyenne, along with their allies the Comanche and Apache, fought and raided Eastern Native Americans who were moving into the Indian Territory.

From 1821 to 1870, the Kiowa joined the Comanche in raids, mostly to get livestock. These raids went deep into Mexico and caused many deaths.

Moving to Reservations

The years from 1873 to 1878 brought big changes to the Kiowa way of life. In June 1874, the Kiowa, along with some Comanche and Cheyenne warriors, made their last major stand against European settlers at the Second Battle of Adobe Walls in Texas. This battle was not successful for them. In 1877, the first homes were built for the Native American chiefs, and a plan began to employ Native Americans at the Agency. Thirty Native Americans were hired to form the first police force on the Reservation.

The Kiowa agreed to settle on a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma. Some Kiowa bands stayed free until 1875. Some Lipan Apache and Mescalero Apache bands, along with some Comanche, remained in northern Mexico until the early 1880s. Then, Mexican and US Army forces forced them onto reservations or caused them to disappear. By the Treaty of Medicine Lodge in 1867, the Kiowa settled in Western Oklahoma and Kansas.

They were forced to move south of the Washita River to the Red River and Western Oklahoma with the Comanches and the Kiowa Apache Tribe. The change from a free life on the Plains to a restricted life on a reservation was harder for some families than others.

Life on the Reservation

The reservation period lasted from 1868 to 1906. In 1873, the first school for the Kiowa was started by a Quaker named Thomas C. Battey. In 1877, the government built the first homes for the chiefs and started a plan to employ Native Americans. Thirty Native Americans were hired to form the first police force on the reservation. In 1879, the agency moved to Anadarko. The 1890 Census showed 1,598 Comanche at the Fort Sill reservation, which they shared with 1,140 Kiowa and 326 Kiowa Apache.

An agreement signed by 456 adult male Kiowa, Comanche, and Kiowa Apache on September 28, 1892, opened the way for white settlers to move into the area. This agreement gave 160 acres of land to every individual in the tribes. It also allowed the sale of the reservation lands (about 2.5 million acres) to the United States. This was supposed to happen right after Congress approved it, even though the Medicine Lodge treaty of 1867 had promised the Native Americans would keep the reservation until 1898. The Native Americans who signed wanted their names removed, but it was too late. A'piatan, a leader, went to Washington to protest. Chief Lone Wolf the Younger immediately took legal action against the act in the Supreme Court. However, the Court decided against him in 1903.

Agents were assigned to work with the Kiowa people during this time.

The Kiowa Today

Since 1968, the Kiowa have been governed by the Kiowa Tribal Council. This council handles matters related to health, education, and economic programs.

On March 13, 1970, the Kiowa Indian Tribe of Oklahoma wrote its constitution and bylaws. Kiowa voters approved them on May 23, 1970. The current constitution was approved in 2017.

In 1998, in an important court case, the US Supreme Court ruled that Native American tribes keep their sovereign immunity. This means they are protected from private lawsuits without their permission, even in business deals off the reservation.

As of 2000, more than 4,000 of the 12,500 enrolled Kiowa lived near the towns of Anadarko, Fort Cobb, and Carnegie in Oklahoma. Many Kiowa also live in cities and suburbs across the United States, having moved for more job opportunities. Each year, Kiowa veterans honor the warrior spirit of their ancestors with dances performed by the Kiowa Gourd Clan and Kiowa Black Leggings Warrior Society. Kiowa culture and pride are strong, especially in their art and the Gourd Dance.

Kiowa Arts and Creativity

The history of modern Kiowa art is very special in Native American culture. As early as 1891, Kiowa artists were asked to create artworks for international exhibitions. The "Kiowa Six" were some of the first Native Americans to become famous around the world for their fine art. They inspired many generations of Native American artists, both among the Kiowa and other Plains tribes. Traditional craft skills are still alive among the Kiowa people today. Talented Kiowa artists and crafters helped the Oklahoma Indian Arts and Crafts Cooperative succeed for 20 years.

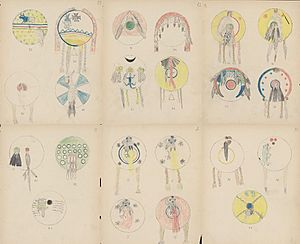

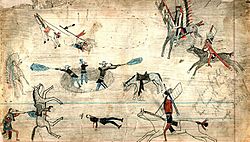

Ledger Art and Hide Painting

Early Kiowa ledger artists were often those held captive by the US Army at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida (1875–1878). This was after the Red River War. Ledger art developed from the tradition of Plains hide painting. These Fort Marion artists included Kiowas like Etadleuh Doanmoe and Zotom. Zotom was a very active artist who drew about his experiences before and after being held captive. After his release, Paul Zom-tiam (Zotom) studied religion and became a deacon in the Episcopal church.

The Kiowa Six

Following in the footsteps of Silver Horn were the Kiowa Six. They were Spencer Asah, James Auchiah, Jack Hokeah, Stephen Mopope, Lois Smoky Kaulaity, and Monroe Tsatoke. These artists came from the area around Anadarko, Oklahoma, and studied at the University of Oklahoma. Lois Smoky left the group in 1927, but James Auchiah joined. The Kiowa Six became internationally famous artists. They showed their work at the 1928 International Art Congress in Czechoslovakia and later at the Venice Biennale in 1932.

Kiowa Artists and Authors

Many Kiowa people have become famous artists and authors.

- Painters and Sculptors: Besides the Kiowa Six and Silver Horn, notable painters include Sharron Ahtone Harjo, Homer Buffalo, T. C. Cannon, Blackbear Bosin, and N. Scott Momaday.

- Beadwork Artists: Famous beadwork artists include Lois Smoky Kaulaity, Vanessa Paukeigope Jennings, Teri Greeves, and Richard Aitson.

- Authors: Kiowa author N. Scott Momaday won the 1969 Pulitzer Prize for his novel House Made of Dawn. Other authors include playwright Hanay Geiogamah and poet Richard Aitson.

- Musicians and Composers: Kiowa music is known for its hymns, often with dance or flute. Notable musicians include James Anquoe, Tom Mauchahty-Ware, and Cornel Pewewardy.

- Photographers: Early Kiowa photographers include Parker McKenzie and his wife Nettie Odlety. Horace Poolaw (1906–1984) was a very important Native American photographer. His grandson, Thomas Poolaw, continues his legacy today.

Images for kids

-

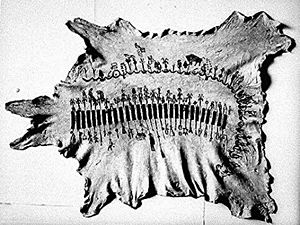

Kiowa parfleche, around 1890, Oklahoma History Center.

-

Kiowa beaded moccasins, around 1920, OHS.

-

Detail of painting by Silver Horn (Kiowa), around 1880.

Kiowa College

In February 2020, the Kiowa tribe officially recognized Bacone College in Muskogee, Oklahoma as its tribal college. In March, the Kiowa Tribal Historian, Phil “Joe Fish” Dupoint, started teaching an 8-week online course in the Kiowa language through the college.

Notable Kiowa People

- Ado-ete (Big Tree) (c.1850–1929), war chief

- Ahpeahtone (1856–1931), chief

- Richard Aitson (1953–2022), bead artist and poet

- Spencer Asah, painter, one of the Kiowa Six

- James Auchiah, painter, one of the Kiowa Six

- Big Bow (Zepko–ette) (1833–c.1900), war chief

- Blackbear Bosin (1921–1980), painter and sculptor

- T. C. Cannon, painter and printmaker

- Cozad Singers, drum group

- Jesse Ed Davis (1944–1988), Kiowa-Comanche guitarist

- Dohäsan (c.1785–1866), principal chief, artist, and calendar keeper

- Teri Greeves (b. 1970), bead artist

- Sharron Ahtone Harjo (b. 1945), painter, ledger artist

- Jack Hokeah, painter, one of the Kiowa Six

- Vanessa Paukeigope Jennings (b. 1952), bead artist, clothing and regalia maker

- Lois Smoky Kaulaity (1907–1981), beadwork artist and painter, one of the Kiowa Six

- Kicking Bird (Tene-angop'te) (1835–1875), war chief

- Guipago (Lone Wolf [the Elder]) (c.1820–1879), principal chief

- Mamanti (Mama'nte) (c. 1835–1875), medicine man

- Mamay-day-te (Lone Wolf [the Younger]) (c. 1843–1923), chief

- Tom Mauchahty-Ware, musician and dancer

- Parker McKenzie (1897–1999), traditionalist and linguist

- N. Scott Momaday (1934–2024), Pulitzer Prize Winner, author, painter, and activist

- Stephen Mopope (1898–1974), painter, one of the Kiowa Six

- Horace Poolaw (1906–1984), photographer

- Pascal Poolaw (1922–1967), Native American war hero

- Satanta (Set'tainte) (c. 1815–1878), war chief

- Silver Horn (1860–1940), artist and calendar keeper

- Sitting Bear (Set-Tank) (c.1800–1871), warrior and medicine man

- Kendal Thompson, professional football player

- Monroe Tsatoke, painter, one of the Kiowa Six

- White Horse (Tsen-tainte) (d. 1892), chief

- Chris Wondolowski, US professional soccer player

- Tahnee Ahtone (b. 1978), curator, artist, and dancer

- Lindy Waters III (b. 1997), professional NBA player

- Mirac Creepingbear (1947–1990), painter

- Sherman Chaddlesone (1947–2013), muralist, sculptor, and painter

See also

In Spanish: Kiowa para niños

In Spanish: Kiowa para niños

- Gourd Dance

- Koitsenko, Kiowa warrior society

- Big Pasture, 1901 Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache grazing reserve

- Kiowa Peak (Texas)