Pemmican facts for kids

Pemmican is a special mixture of animal fat, dried meat, and dried berries. It's a super nutritious food! Long ago, it was a very important part of the diet for Indigenous peoples in North America. People still make it today.

The word "pemmican" comes from the Cree language, from the word pimîhkân, which means "fat" or "grease." The Lakota people call their version wasná. It was invented by the Indigenous peoples of North America.

Europeans quickly started using pemmican too. It was a great high-energy food for fur traders. Later, brave explorers in the Arctic and Antarctic, like Ernest Shackleton and Roald Amundsen, also relied on it for their long journeys.

Contents

What's in Pemmican?

Traditionally, people used whatever ingredients they had available. The dried meat often came from large animals like bison, deer, elk, or moose. Sometimes, fish like salmon or smaller animals like duck were used. Today, some pemmican recipes also include beef.

Dried fruits are often added for extra flavor and nutrients. Common fruits include cranberries and Saskatoon berries. You might also find blueberries, cherries, chokeberries, and currants. These fruits are sometimes used for special ceremonial pemmican. All these ingredients are mixed with melted animal fat, called tallow.

The Lakota and Dakota nations also make a type of wasná (or pemmican) from toasted cornmeal. This version doesn't have dried meat. It's made with cornmeal, animal fat, fruit, and sugar.

How Pemmican Was Made

Making traditional pemmican started with lean meat from large animals like bison or elk. The meat was cut into thin slices. Then, it was dried over a slow fire or in the hot sun until it became very hard and brittle. About five pounds of fresh meat were needed to make one pound of dried meat. This dried meat was called pânsâwân by the Cree people.

Next, the thin, brittle meat was spread out on a tanned animal hide. It was then beaten with tools or ground between two large stones. This turned the meat into very small pieces, almost like a powder. The pounded meat was then mixed with melted fat. Usually, this was melted suet (animal fat) that had been turned into tallow. They used about equal amounts of meat and fat.

Sometimes, dried fruits like blueberries or Saskatoon berries were also pounded into powder. These fruit powders were then added to the meat and fat mixture. The finished mixture was packed into rawhide bags. Inside these bags, the pemmican would cool and harden.

Today, some people store their homemade pemmican in glass jars or tin boxes. Pemmican can last a long time. At room temperature, it can stay good for one to five years. Some stories say pemmican stored in cool cellars has been eaten safely after more than ten years! If it's vacuum-sealed, it might even be edible after more than a century.

A large bag of bison pemmican, weighing about 90 pounds, was called a taureau by the Métis people. Different types of taureaux were made. For example, taureaux à grains had berries mixed in. It usually took the meat from one bison to fill a taureau bag.

How Pemmican Was Eaten

In 1874, a police officer named Sam Steele wrote about three ways to eat pemmican.

- Raw: Some people ate it just as it was.

- Rubaboo: This was a stew made by boiling pemmican with water, flour, and sometimes wild onions or potatoes.

- Rechaud: This was pemmican fried in a pan, often with onions and potatoes.

Sam Steele himself said he never liked eating it raw.

History of Pemmican

Pemmican was very important for the voyageurs during the Canadian fur trade. These traders traveled long distances by canoe. They didn't have time to hunt or gather food along the way. So, they needed to carry all their food with them. Pemmican was perfect because it was light and full of energy.

The Métis people played a big role in the pemmican trade. They would go out onto the prairies in Red River carts to hunt bison. They would turn the bison meat into pemmican. Then, they would carry it north to trade with the fur trading posts. For the Métis, selling pemmican was as important as trading beaver furs was for other Indigenous groups. This trade helped create the unique Métis society.

Pemmican was so important that in 1814, a governor named Miles Macdonell tried to stop its export from the Red River Colony. This led to a conflict known as the Pemmican War with the Métis.

Many famous explorers used pemmican. Alexander Mackenzie relied on it for his journey across Canada to the Pacific in 1793. North Pole explorer Robert Peary used pemmican for his men and dogs on all his expeditions from 1886 to 1909. He said it was absolutely necessary for a successful polar journey.

British polar expeditions also fed a type of pemmican to their sled dogs. When Ernest Shackleton's expedition was stuck on ice in the Antarctic, his men even ate the dog pemmican to survive!

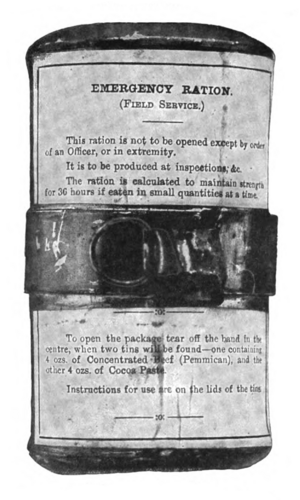

During the Second Boer War (1899–1902), British soldiers carried an "iron ration." This was a small amount of pemmican, chocolate, and sugar. It was kept in small tins and was only eaten as a last resort when ordered by an officer. This ration could help a soldier keep going for 36 hours without other food.

Pemmican Today

Today, many Indigenous communities in North America still make pemmican. They use it for their families, community events, and ceremonies. Some modern recipes might use ingredients like beef, which were brought to the Americas later.

There are also Indigenous-owned companies that make pemmican or foods based on traditional pemmican recipes. An example is Tanka Bar, which sells pemmican-based snacks.

See also

In Spanish: Pemmican para niños

In Spanish: Pemmican para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |