Blackfoot Confederacy facts for kids

{{Infobox ethnic group |group=Blackfoot, Niitsítapi, Siksikaitsitapi ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ

|image=

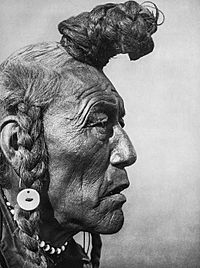

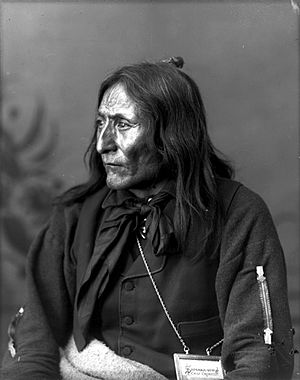

Bear Bull, a Blackfoot translator, photographed in 1926.

|population=32,000 |popplace=![]() Canada

Canada

(![]() Saskatchewan,

Saskatchewan, ![]() Alberta, {{flagicon|British Columbia]] (part))

Alberta, {{flagicon|British Columbia]] (part))

![]() United States

United States

(![]() Montana, {{country data Wyoming]] (part)

Montana, {{country data Wyoming]] (part) ![]() ) |flagicon/core|variant=|size=}} The Blackfoot Confederacy, also known as Niitsitapi or Siksikaitsitapi (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ), means "the people" or "Blackfoot-speaking real people." This is a historical name for groups of people who speak similar languages and are part of the Blackfoot or Blackfeet people.

) |flagicon/core|variant=|size=}} The Blackfoot Confederacy, also known as Niitsitapi or Siksikaitsitapi (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ), means "the people" or "Blackfoot-speaking real people." This is a historical name for groups of people who speak similar languages and are part of the Blackfoot or Blackfeet people.

The main groups are the Siksika ("Blackfoot"), the Kainai or Kainah ("Blood"), and two parts of the Piikani (Piegan Blackfeet): the Northern Piikani and the Southern Piikani. Sometimes, other groups like the Tsúùtínà (Sarcee) and A'aninin (Gros Ventre) were also part of the Blackfoot Confederacy, even though they spoke different languages.

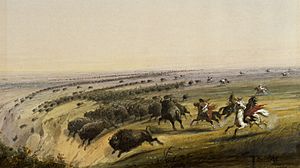

Historically, the Blackfoot people were nomadic hunters of bison and fishermen. They traveled across the northern Great Plains in western North America. They followed the bison herds as they moved between what are now the United States and Canada. In the early 1700s, they got horses and firearms from traders. They used these to expand their territory.

Today, three Blackfoot groups in Canada are called First Nation governments. These are the Siksika Nation, Kainai Nation, and Piikani Nation. They live in Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia. In the United States, the Blackfeet Tribe is a recognized Native American group in Montana. The Gros Ventre are part of the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in the U.S., and the Tsuutʼina Nation is a First Nation in Alberta, Canada.

Contents

How the Blackfoot Confederacy Was Governed

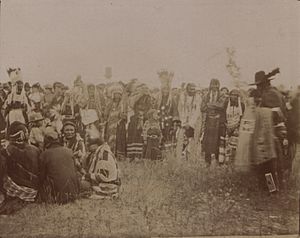

The four Blackfoot nations form the Blackfoot Confederacy. This means they joined together to help each other. Each nation has its own government led by a head chief. However, they often gather for religious and social events.

Originally, the Blackfoot Confederacy had three main groups. These groups were based on family ties and how they spoke their language. All of them spoke the Blackfoot language, which is part of the Algonquian languages family. The three groups were the Piikáni (also called "Piegan Blackfeet"), the Káínaa (called "Bloods"), and the Siksikáwa ("Blackfoot"). Later, they allied with the Tsuu T'ina ("Sarcee") and, for a time, with the Atsina or A'aninin (Gros Ventre).

Each of these groups was divided into many smaller bands. A band could have 10 to 30 lodges, which meant about 80 to 240 people. The band was the main group for hunting and for defense.

The Confederacy lived in a large area where they hunted and gathered food. In the 1800s, this area was split by the border between Canada and the United States. Later in the 1800s, both governments made the Blackfoot people stop their nomadic way of life. They had to settle on "Indian reserves" in Canada or "Indian reservations" in the U.S. The South Peigan were the only group who chose to live in Montana. The other three Blackfoot-speaking groups and the Sarcee settled in Alberta. Together, the Blackfoot-speakers call themselves the Niitsítapi, meaning the "Original People." The Gros Ventres also settled on a reservation in Montana after leaving the Confederacy.

When they had to stop their nomadic life, their social structures changed. The tribal nations, which were mostly groups of people with shared backgrounds, became official governments. The Piegan group was divided into the North Peigan in Alberta and the South Peigan in Montana.

Blackfoot History and Way of Life

The Blackfoot Confederacy once had a large territory. It stretched from the North Saskatchewan River in what is now Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, down to the Yellowstone River in Montana, United States. It also went from the Rocky Mountains to the Alberta-Saskatchewan border. They called their land Niitsitpiis-stahkoii (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᐨᑯᐧ ᓴᐦᖾᐟ), which means "Original People's Land." They started using horses in the early 1700s. Horses helped them travel farther and hunt better.

The basic social group for the Niitsitapi was the band. A band had about 10 to 30 lodges, which meant about 80 to 241 people. This size was good for defending themselves and hunting together. Each band had a respected leader, often with his family, and other people who were not related. People could leave one band and join another if they wanted. This made the system flexible and good for a hunting people on the northwestern Great Plains.

In the summer, the people gathered for large meetings. During these gatherings, warrior societies were very important for the men. Men joined these societies by showing brave acts.

For almost half the year, during the long northern winter, the Niitsitapi lived in winter camps. These camps were in wooded river valleys. They would only move if they ran out of food for people and horses, or firewood. Sometimes, several bands would camp together if there was enough wood and game. During winter, buffalo also stayed in wooded areas, where they were safer from storms and snow. This made them easier to hunt. In spring, the buffalo moved to the grasslands. The Blackfoot would follow them once the risk of late blizzards passed.

In midsummer, when chokecherries were ripe, the people gathered for their main ceremony, the Okan (Sun Dance). This was the only time all four nations would come together. This gathering strengthened the bonds between the groups. Communal buffalo hunts provided food, and buffalo tongues were offered in the ceremonies. These ceremonies are very sacred. After the Okan, the people separated again to follow the buffalo. They used buffalo hides to make their homes and temporary tipis.

In the fall, the people slowly moved to their winter areas. The men would prepare buffalo jumps and pounds to catch bison for hunting. Several groups might join at good hunting spots, like Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. As the buffalo moved into the area, the Blackfoot would have large communal buffalo kills.

The women prepared the buffalo meat. They dried it and mixed it with dried fruits to make pemmican. This food lasted through winter and times when hunting was difficult. At the end of fall, the Blackfoot moved to their winter camps. The women also prepared buffalo and other animal skins for clothing and to make their homes stronger. They used other parts of the animals for warm fur robes, leggings, cords, and other items. Animal tendons were used to tie arrow points and lances, or for horse bridles.

The Niitsitapi kept this traditional way of life until the buffalo almost disappeared by 1881. This forced them to change their ways because of the arrival of European settlers. In the United States, they were given land in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. Later, they received a specific reservation in the Sweetgrass Hills Treaty of 1887. In 1877, the Canadian Niitsitapi signed Treaty 7 and settled on reserves in southern Alberta.

This time was very difficult and brought economic hardship. The Niitsitapi had to learn a completely new way of life. Many people died from European diseases because they had no natural protection against them.

Eventually, they developed a stable economy based on farming, ranching, and small industries. Their population has grown to about 16,000 in Canada and 15,000 in the U.S. today. With more economic stability, the Niitsitapi have been able to adapt their culture and traditions, reconnecting with their ancient roots.

Early Blackfoot History

The Niitsitapi, also known as the Blackfoot or Blackfeet Indians, live in the Great Plains of Montana and the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Originally, only one of the Niitsitapi tribes was called Blackfoot or Siksika. The name is believed to come from the color of their moccasins, which were made of leather. They often dyed or painted the soles of their moccasins black. One story says that the Siksika walked through the ashes of prairie fires, which made the bottoms of their moccasins black.

Experts who study human cultures believe the Niitsitapi did not start in the Great Plains. They think the Blackfoot moved from the northeastern part of North America. They came together as a group while living in the forests of what is now the Northeastern United States, near the modern border between Canada and Maine. By 1200, the Niitsitapi were moving to find more land. They moved west and lived for a while north of the Great Lakes in Canada. However, they had to compete with other tribes for resources. So, they left the Great Lakes area and kept moving west.

When they moved, they usually packed their belongings on an A-shaped sled called a travois. The travois was made for carrying things over dry land. The Blackfoot used dogs to pull the travois because they did not get horses until the 1700s. From the Great Lakes area, they continued west and eventually settled in the Great Plains.

The Plains covered a huge area, about 780,000 square miles. It stretched from the Saskatchewan River in the north to the Rio Grande in the south, and from the Mississippi River in the east to the Rocky Mountains in the west. After getting horses, the Niitsitapi became one of the most powerful Native American tribes on the Plains in the late 1700s. They earned the name "The Lords of the Plains." Blackfoot stories say they have lived on their plains territory since "time immemorial," meaning for a very long time.

The Importance of Bison

The main food source for the Niitsitapi on the plains was the American bison (buffalo). Bison are the largest mammals in North America, standing about 6.5 feet tall and weighing up to 2,000 pounds. Before horses, the Niitsitapi had other ways to hunt them. A "buffalo jump" was a common method. Hunters would gather the buffalo into V-shaped pens and then drive them over a cliff. They hunted pronghorn antelopes in the same way. After the buffalo fell, hunters would go to the bottom and take as much meat as they could carry back to camp.

They also used camouflage for hunting. Hunters would use buffalo skins from earlier hunts. They would drape the skins over their bodies to blend in and hide their scent. By moving carefully, hunters could get close to the herd. Once close enough, they would use arrows or spears to kill wounded animals.

The Blackfoot people used almost every part of the buffalo. Women prepared the meat by boiling, roasting, or drying it to make jerky. This made the meat last a long time without spoiling, which was important for getting through the winters. Winters were long, harsh, and cold on the Plains because there were few trees. So, people stored a lot of meat in the summer. As a ritual, hunters often ate the bison heart right after a kill.

Women also tanned and prepared the skins to cover their tepees. Tepees were made of log poles with skins draped over them. They stayed warm in winter and cool in summer, and protected well against the wind. Women also made clothing from the skins, like robes and moccasins, and made soap from the fat. Both men and women made tools, sewing needles, and utensils from the bones. They used tendons for tying things. The stomach and bladder were cleaned and used to store liquids. Dried buffalo dung was used as fuel for fires. The Niitsitapi saw the buffalo as sacred and essential to their lives.

How Horses Changed Life

Before about 1730, the Blackfoot traveled by foot and used dogs to carry their goods. They had not seen horses in their old lands. But on the Plains, other tribes like the Shoshone already used horses. The Blackfoot saw how useful horses were and wanted them. The Blackfoot called horses ponokamita, meaning "elk dogs." Horses could carry much more weight than dogs and moved faster. They could be ridden for hunting and travel.

Horses changed life on the Great Plains completely. Soon, horses became a sign of wealth. Warriors often raided other tribes to get their best horses. Horses were also used for trading. Medicine men were paid with horses for healing people. Those who designed shields or war bonnets were also paid in horses. Men gave horses to people who were owed gifts or to those in need. A person's wealth grew with the number of horses they had. However, a man did not keep too many horses. A person's respect and status were judged by how many horses they could give away. For the Native Americans on the Plains, sharing property with others was very important.

After driving the Shoshone and Arapaho from the Northwestern Plains, the Niitsitapi began a long period of competition with their former Cree allies in the fur trade around 1800. This often led to fighting. Both groups had started using horses around 1730, so by the mid-1700s, having enough horses was important for survival. Stealing horses was not just a sign of bravery, but often a way to survive, as many groups competed for hunting grounds.

The Cree and Assiniboine continued to raid the Gros Ventre for horses. The Gros Ventre were allies of the Niitsitapi. In return for the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) giving weapons to their enemies, the Gros Ventre attacked and burned the HBC's South Branch House in 1793. This was near the village of St. Louis, Saskatchewan. Then, the tribe moved south to the Milk River in Montana and allied with the Blackfoot. The area between the North Saskatchewan River and Battle River became the boundary between the warring tribal alliances.

Blackfoot Culture and Traditions

Choosing Leaders

Family was very important to the Blackfoot people. For traveling, they split into bands of 20-30 people. But they would gather for celebrations. They valued good leadership skills and chose chiefs who could lead their settlements wisely. During peaceful times, they would elect a "peace chief." This person would lead the people and improve relationships with other tribes. The title of "war chief" could not be gained by election. It had to be earned by successfully performing brave acts, like touching a living enemy in battle. Blackfoot bands often had minor chiefs in addition to a main head chief.

Societies and Roles

Within the Blackfoot nation, there were different societies that people belonged to. Each society had specific roles for the tribe. Young people were invited into societies after proving themselves through recognized steps and ceremonies. For example, young men had to go on a vision quest. This started with a spiritual cleansing in a sweat lodge. They would then go alone from the camp for four days, fasting and praying. Their main goal was to see a vision that would show them their future. After having a vision, a young person returned to the village ready to join society.

In a warrior society, the men had to be ready for battle. Warriors would prepare by spiritual cleansing. Then, they would paint themselves with symbols. They often painted their horses for war too. Leaders of the warrior society carried spears or lances called a coup stick. These were decorated with feathers, skin, and other items. Warriors gained respect by "counting coup." This meant tapping an enemy with the stick and getting away safely.

Members of the religious society protected sacred Blackfoot items and performed religious ceremonies. They blessed the warriors before battle. Their most important ceremony was the Sun Dance, or Medicine Lodge Ceremony. By taking part in the Sun Dance, their prayers would go to the Creator. The Creator would then bless them with good health and many buffalo.

Women's societies also had important jobs for the tribe. They created beautiful quillwork on clothing and ceremonial shields. They helped prepare for battle, and they prepared skins and cloth for making clothes. They cared for children and taught them tribal ways. They also skinned and tanned leathers for clothing and other uses. Women prepared fresh and dried foods. They also performed ceremonies to help hunters on their journeys.

Marriage Customs

In Blackfoot culture, men were responsible for choosing their marriage partners. However, women had the choice to accept or refuse them. The man had to show the woman’s father his skills as a hunter or warrior. If the father was impressed and approved the marriage, the man and woman would exchange gifts of horses and clothing. After this, they were considered married. The married couple would live in their own tipi or with the husband’s family. Although a man was allowed to have more than one wife, most men chose only one. If a man did have more than one wife, he often chose a sister of his first wife. This was because they believed sisters would argue less than strangers.

Daily Life and Clothing

In a typical Blackfoot family, the father would hunt and bring back supplies. The mother would stay close to home and care for the children while the father was away. Children learned basic survival skills and culture as they grew up. Both boys and girls usually learned to ride horses early. Boys would play with toy bows and arrows until they were old enough to hunt. They also played a popular game called shinny, which later became known as ice hockey. They used a long, curved wooden stick to hit a ball, made of baked clay covered with buckskin, over a goal line. Girls were given a doll to play with. This doll also helped them learn, as it was dressed in typical tribal clothing and designs, teaching young women how to care for a child. As they got older, they had more responsibilities. Girls were taught to cook, prepare hides for leather, and gather wild plants and berries. Boys were responsible for going out with their father to hunt for food.

Clothing was usually made from softened and tanned antelope and deer hides. The women made and decorated the clothes for everyone in the tribe. Men wore moccasins, long leggings that went up to their hips, a loincloth, and a belt. Sometimes they wore shirts, but usually they wrapped buffalo robes around their shoulders. Brave and respected men wore necklaces made of grizzly bear claws. Boys dressed much like older males, wearing leggings, loincloths, moccasins, and sometimes an undecorated shirt. They stayed warm by wearing a buffalo robe over their shoulders or over their heads if it was cold. Women and girls wore dresses made from two or three deerskins. Women liked to wear earrings and bracelets made from sea shells, which they traded for, or different types of metal. They would sometimes wear beads in their hair or paint the part in their hair red. This red color showed that they could still have children.

The Blackfoot Creation Story

The creation myth is a story passed down through generations in the Blackfoot Nation. It tells how, in the beginning, Napio floated on a log with four animals: Mameo (fish), Matcekups (frog), Maniskeo (lizard), and Sopeo (turtle). Napio sent each animal into the deep water. The first three came back with nothing. The turtle went down and brought back mud from the bottom. Napio took the mud, rolled it in his hand, and created the earth. He let it roll out of his hand, and over time, it grew into what it is today. After creating the earth, he created women and then men. He had them live separately at first. The men were shy and afraid, but Napio told them not to fear and to choose one as their wife. They did as he asked. Napio then created the buffalo and bows and arrows so the people could hunt them.

Modern Blackfoot Communities

Economy and Services

Today, many Blackfoot people live on reserves in Canada. About 8,500 live on the Montana reservation, which is about 1.5 million acres. In 1896, the Blackfoot sold a large part of their land to the United States government. The government hoped to find gold or copper there, but no such minerals were found. In 1910, that land became Glacier National Park. Some Blackfoot people work there, and Native American ceremonies are sometimes held there.

Unemployment is a challenge on the Blackfeet Reservation and Canadian Blackfoot reserves. This is because they are far from major cities. Many people work as farmers, but there are not enough other jobs nearby. To find work, many Blackfoot have moved from the reservation to towns and cities. Some companies pay the Blackfoot governments to use their lands for oil, natural gas, and other resources. The nations have also run businesses, like the Blackfoot Writing Company, a pen and pencil factory that opened in 1972 but closed in the late 1990s. In Canada, the Northern Piegan make traditional craft clothing and moccasins. The Kainai operate a shopping center and a factory.

In 1974, the Blackfoot Community College, a tribal college, opened in Browning, Montana. This school is also where the tribal headquarters are located. Since 1979, the Montana state government requires all public school teachers on or near the reservation to have knowledge of American Indian studies.

In 1986, the Kainai Nation opened the Red Crow Community College in Stand Off, Alberta. In 1989, the Siksika tribe in Canada built a high school to go along with its elementary school.

Continuing Traditions

The Blackfoot people continue many cultural traditions from the past. They hope to pass on their ancestors' traditions to their children. They want to teach their children the Pikuni language and other traditional knowledge. In the early 1900s, a woman named Frances Densmore helped the Blackfoot record their language. During the 1950s and 1960s, few Blackfoot people spoke the Pikuni language. To save their language, the Blackfoot Council asked elders who still knew the language to teach it. The elders agreed and successfully helped bring the language back. Today, children can learn Pikuni at school or at home. In 1994, the Blackfoot Council made Pikuni the official language.

The people have also brought back the Black Lodge Society. This group is responsible for protecting Blackfoot songs and dances. They continue to announce the coming of spring by opening five medicine bundles. They do this every time they hear thunder in the spring. One of the biggest celebrations is called the North American Indian Days. It lasts four days and is held during the second week of July in Browning. Finally, the Sun Dance, which was illegal from the 1890s to 1934, has been practiced again for many years. While it was illegal, the Blackfoot held it in secret. Since 1934, they have practiced it every summer. The event lasts eight days and is filled with prayers, dancing, singing, and offerings to honor the Creator. It is a chance for the Blackfoot to gather, share ideas, and celebrate their most sacred ceremonies.

The Blackfeet Nation in Montana has a blue tribal flag. The flag shows a ceremonial lance or coup stick with 29 feathers. In the center of the flag is a ring of 32 white and black eagle feathers. Inside the ring is an outline map of the Blackfoot Reservation. Within the map, there is a warrior's headdress and the words "Blackfeet Nation" and "Pikuni" (the name of the tribe in the Algonquian native tongue of the Blackfoot).

Notable Blackfoot People

- Elouise Cobell: A banker and activist who led a major lawsuit in the 20th century. This lawsuit made the U.S. Government change how it managed money for Native Americans.

- Byron Chief-Moon: A performer and choreographer.

- Crowfoot (ISAPO-MUXIKA – "Crow Indian's Big Foot"): A powerful chief of the South Siksika.

- Aatsista-Mahkan ("Running Rabbit"): A chief of the Biters band of the Siksika. He signed Treaty No.7 in 1877.

- A-ca-oo-mah-ca-ye (Ac ko mok ki, A'kow-muk-ai – "Feathers"): A chief of the Old Feathers' band, also known as Old Swan.

- Stu-mick-o-súcks ("Buffalo Bull's Back Fat"): The Head Chief of the Kainai.

- Faye HeavyShield: A Kainai sculptor and installation artist.

- Joe Hipp: A heavyweight boxer and the first Native American to compete for a major world heavyweight boxing title.

- Beverly Hungry Wolf: An author.

- Stephen Graham Jones: An author.

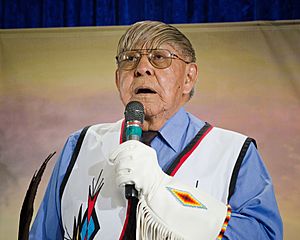

- Earl Old Person: Blackfoot tribal chairman for many years and an honorary lifetime chief.

- Jerry Potts: A plainsman, buffalo hunter, horse trader, interpreter, and scout of Kainai-Scottish background. He became a minor Kainai chief.

- Steve Reevis: An actor who appeared in films like Fargo and Dances with Wolves.

- Misty Upham: An actress.

- James Welch: A Blackfoot-Gros Ventre author.

- The Honourable Eugene Creighton: A judge of the Provincial Court of Alberta.

- Gyasi Ross: An author, attorney, musician, and political activist.

Blackfoot in Other Media

- Hergé's Tintin in America (1932) features Blackfoot people.

- Jimmy P (2013) is a French-American film. It explores the story of Jimmy Picard, a Blackfoot man, after World War II. A psychoanalyst helps him at a veterans' hospital.

Images for kids

-

The Death of Omoxesisixany or Big Snake by Paul Kane, showing a battle between a Blackfoot and Plains Cree warrior on horseback.

-

Buffalo Bull's Back Fat, Head Chief, of the Blood Tribe by George Catlin.

-

Colorized photograph of chief Mountain Chief.

-

Frances Densmore recording chief Mountain Chief for the Bureau of American Ethnology in 1916.

-

Horned bonnet with ermine skin.

-

Head Carry, a Piegan man wearing a split horn headdress. Photographed by Edward S. Curtis, 1900.

-

Headdress Case, Blackfoot (Native American), late 19th century, Brooklyn Museum.

-

A Siksika Blackfeet Medicine Man, painted by George Catlin.

See also

In Spanish: Pies negros para niños

In Spanish: Pies negros para niños