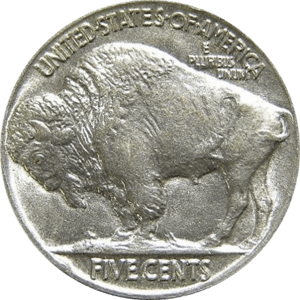

Bison hunting facts for kids

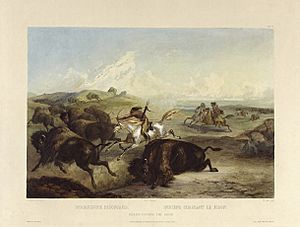

Bison hunting was a super important activity for the Plains Indians who lived in the huge grasslands of North America. They hunted the American bison, also called the American buffalo. This hunting was key to their way of life and their society.

However, in the late 1800s, the bison almost completely disappeared. This happened after the United States started expanding westward. Bison hunting was also a spiritual practice for these groups. After Europeans brought horses to America between the 1500s and 1700s, new hunting methods became possible.

The huge drop in bison numbers happened because their homes were destroyed by farms and ranches. Also, non-Native hunters killed many bison for their hides and meat. Native hunting also increased because of demand from others. Sometimes, governments even tried to destroy the bison on purpose to weaken Native American groups during conflicts.

Contents

Bison Hunting Through History

Ancient Bison and Early Humans

Long, long ago, over a million years ago, a type of bison called the steppe bison lived in North America. This was even before the first humans arrived! Over time, this bison changed into bigger types, like the giant Ice Age bison.

The first humans in North America, called Paleo-Indians, hunted these ancient bison. But they also hunted other large animals like mammoths, mastodons, and horses. Around 11,000 to 10,000 years ago, most of these large animals disappeared. The bison was one of the few big animals that survived. It eventually evolved into the smaller American bison we know today, about 5,000 years ago.

Native American Plains Bison Hunting

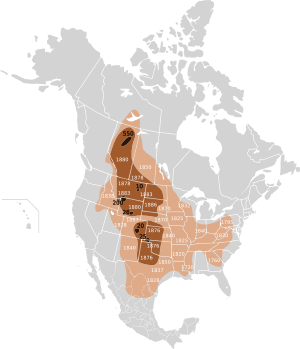

Today, there are two types of American bison: the wood bison in Canada's forests and the plains bison on the prairies from Canada to Mexico. The plains bison became super important on the North American prairies. They were a "keystone species," meaning they played a huge role in shaping the environment through their grazing. They were also central to the survival of many Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains.

Some historians believe that Native Americans actually helped create the large grasslands where bison lived by using controlled fires. They might have also helped control the bison population. When European diseases arrived in the 1500s, many Native people died. This might have led to the bison herds growing much larger than before, as there were fewer people to hunt them.

Native Americans had many clever ways to hunt bison. Sometimes, they would use fires to guide a whole herd of bison over a cliff. This was called a buffalo jump. They would also build large corrals called buffalo pounds to trap the animals. The Olsen–Chubbuck Bison Kill Site in Colorado shows how they would butcher the animals quickly and efficiently, using every part. For example, they would dry tough meat to make pemmican, a nutritious food.

A Crow historian shared that they used songs and special drive lines of stones to guide bison over cliffs. One successful drive could bring in 700 animals! In winter, they would sometimes trick bison onto slippery ice, where they were easier to hunt.

In 1691, explorer Henry Kelsey described how a tribe would surround a herd, making the circle smaller and smaller until they could hunt the animals. The hunters would kill as many as they could before the bison broke through the human ring.

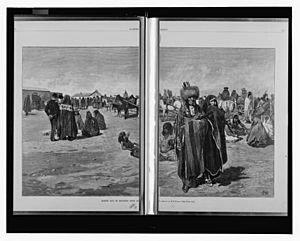

Native American women were very skilled at butchering bison. A Spanish soldier named Castaneda was amazed at how quickly they could do it using simple tools. They would even use emptied guts to carry blood to drink!

Religion was also a big part of Native American bison hunting. Many Plains tribes believed that successful hunts needed special rituals and prayers. The Omaha tribe would stop four times when approaching a herd to smoke and pray for success. The Pawnee had a special "Big Washing Ceremony" before their summer hunts to avoid scaring the bison. To these tribes, the buffalo was a very sacred animal, and they treated it with great respect. They would offer a prayer before killing a buffalo.

Horses Change Hunting

Before horses, Native Americans herded bison into traps or over cliffs. But when horses arrived from the Spanish in the early 1700s, everything changed. Horses made hunting much easier and faster. Indigenous groups who lived east of the Great Plains moved west to hunt the larger bison herds.

Tribal conflicts sometimes forced groups like the Cheyenne to move west and become skilled horseback bison hunters. These groups not only used bison for themselves but also traded meat and hides to other tribes.

A good horseman could easily hunt enough bison to feed his tribe and family. Bison provided meat, leather, and sinew for bows. Hunters would use arrows marked in a personal way to show who killed which animal. A traveler once noted how quickly hunters could cut up a bison and pack the meat on a horse – in less than 15 minutes!

When bison were scarce, tribes faced severe hunger. Stories and myths often shared these difficult times.

Bison Herds Shrink and Tribes are Affected

The hunting of bison sometimes led to conflicts between different Native American groups who relied on the same food source. It also caused tribes to lose land, suffer economically, and lose some of their independence.

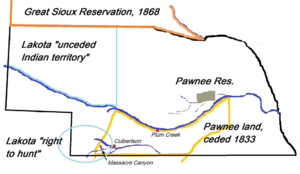

Loss of Land and Hunting Grounds

Tribes pushed away from good hunting areas had to try their luck elsewhere. Smaller tribes found it especially hard. For example, in the 1850s and 1860s, villages along the Upper Missouri River hardly dared to go hunt buffalo because of attacks.

The Kiowa people, for instance, fought the Cheyenne over hunting rights in Montana and South Dakota. Later, the Kiowas moved south with the Comanche after the Lakota drove them from the Black Hills. In Montana, the well-armed Blackfoot pushed other tribes like the Kutenai and Eastern Shoshone off the plains. These tribes west of the Rocky Mountains didn't accept this, as their ancestors had hunted there. A Flathead chief said, "When we go to hunt Bison, we also prepare for war."

Conflicts between bison hunting tribes included raids and battles. Camps could be left without leaders, and homes destroyed. Organized hunts were stopped, and villages had to flee.

Bison Hunting in the 1800s and Near Extinction

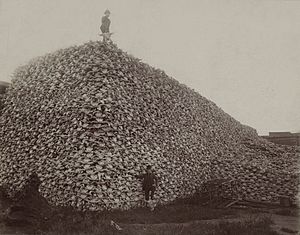

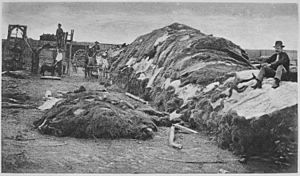

Bison were hunted almost to extinction in the 1800s. By the late 1880s, fewer than 100 remained in the wild. They were hunted mainly for their skins and tongues, with the rest of the animal often left to rot. After the animals decayed, their bones were collected and shipped east in huge amounts.

Bison tend to gather around a fallen member of their herd. This made it easy for hunters to kill many animals at once. If one bison was killed, others would gather around it, allowing hunters to destroy a large herd.

In 1889, a journal article noted how millions of bison once roamed the continent. But for 20 years or more, thousands were killed by white hunters and tourists just for their hides or for fun. Their bodies were left to rot, and their bones scattered across the plains.

The exact reasons for this huge drop in bison numbers are still debated. Some argue that Native people also contributed to the decline by adapting to new hunting methods with horses and trading more hides and meat.

Commercial Hunting and Other Reasons

For settlers, hunting bison was a way to make money. Trappers and traders sold buffalo fur. In one winter (1872–1873), over 1.5 million buffalo hides were sent east by train. Buffalo leather was used for machinery belts and army boots.

Commercial bison hunters became very common. They were often supported by military forts. While officers hunted for food and sport, professional hunters had a much bigger impact. Famous hunters like "Buffalo Bill" Cody would kill hundreds of animals in a single hunt and thousands in their careers. One hunter claimed to have killed over 20,000 bison!

The average price for a cow hide in the 1880s was about $3. These hunters would find a herd, get about 100 yards away, and shoot the animals through the lungs. They avoided head shots because the bullets might not go through the thick skull. If done right, many bison would fall at once. Then, skinners would quickly remove the hides.

For about a decade after 1873, hundreds, maybe even over a thousand, commercial hunting groups were active. They killed far more bison than Native Americans or individual hunters. It's estimated they killed anywhere from 2,000 to 100,000 animals per day, depending on the season.

The building of railroads through Colorado and Kansas split the bison herds into two parts: a southern herd and a northern herd. The last remaining southern herd was in the Texas Panhandle.

Military Involvement

The U.S. Army actually supported the killing of bison herds. The government encouraged bison hunting to force Native people onto Indian reservations during conflicts. Without their main food source, Native people often had to leave their land or face severe hunger. General William Tecumseh Sherman was a big supporter of this idea. He believed that killing buffalo was the quickest way to make Native Americans settle down.

Railroad Involvement

After the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862, many more settlers moved west, and the bison population dropped sharply. As railroads expanded, military troops and supplies could be moved more easily. Some railroads even hired hunters to feed their workers. William Frederick "Buffalo Bill" Cody worked for the Kansas Pacific Railway for this reason.

Trains would often slow down to allow passengers to shoot at herds from the windows or roofs. The railroad industry also wanted bison gone because large herds on the tracks could damage trains or delay them for days.

Bison Population Crash and its Effect on Indigenous People

After the Civil War, the U.S. made many treaties with Plains tribes, but often broke them as more settlers moved west. The huge drop in bison numbers meant a great loss of spirit, land, and independence for most Indigenous people.

Loss of Land and Food

Much of the land given to Indigenous tribes during this expansion was dry and far from any buffalo herds. These reservations couldn't support Native people who relied on bison for food. For example, the Sand Creek Reservation in Colorado was over 200 miles from the nearest buffalo. Many Cheyenne people had to leave the reservation to hunt settlers' livestock.

Plains Indians had a nomadic lifestyle, moving to follow the bison. Bison meat was very healthy, high in protein and low in fat. Native Americans used every part of the bison, including organs and brains.

Loss of Independence

Because of the great bison slaughter, Native Americans became more dependent on the U.S. Government and American traders. Many military leaders saw the bison slaughter as a way to reduce the independence of Indigenous peoples. For example, Lieutenant Colonel Dodge said, "Either the buffalo or the Indian must go. Only when the Indian becomes absolutely dependent on us... will we be able to handle him."

The destruction of bison marked the end of the Indian Wars and the movement of tribes onto reservations. When the Texas government suggested a bill to protect bison, General Philip Sheridan disagreed. He said that the hunters were "destroying the Indians' commissary" (their food supply). He believed that killing all the buffalo would lead to lasting peace, and then the prairies could be covered with cattle.

Spiritual Effects

Most Native American tribes saw the bison as a sacred animal and a religious symbol. Many tribes believed that the buffalo came from creation stories and was deeply spiritual. The buffalo was used in ceremonies, for homes (tipis), tools, shields, and even for sewing. Some tribes had "buffalo doctors" who learned from bison in visions. Many Plains tribes used bison skulls for confessions and to bless burial sites.

Many tribes believed the buffalo were a gift from the Creator and would always be there. They didn't understand the idea of a species going extinct. So, when the buffalo started disappearing in huge numbers, it was very upsetting. Crow Chief Plenty Coups said, "When the buffalo went away, the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again."

Spiritual loss was widespread. Buffalo were a key part of their society, and they often held ceremonies to honor each buffalo they killed. To keep spirits up, tribes like the Sioux performed the Ghost Dance, where many people would dance until they became unconscious.

Native Americans were the traditional caretakers of bison. Being forced to move to areas without bison was very hard. On reservations, some tribes asked if they could hunt cattle like they hunted buffalo. During these "cattle hunts," they would dress up, sing bison songs, and try to make it feel like a real bison hunt. This helped them keep their ceremonies and community spirit alive. However, the U.S. government soon stopped these cattle hunts and instead gave them packaged beef.

Ecological Effect

The mass killing of buffalo also seriously harmed the environment of the Great Plains. Unlike cattle, bison were naturally suited to the Plains. Their large heads helped them push through snow in winter. Bison grazing also helped the prairie grow a wide variety of plants.

Cattle, on the other hand, eat vegetation differently and can limit the ecosystem's ability to support diverse plants. It's estimated that agricultural development has reduced the prairie to only 0.1% of its original size. The Plains region has lost almost one-third of its topsoil since the buffalo slaughter. Cattle also use a lot of water, which is emptying many underground water sources. Research suggests that without native grasses, topsoil erosion increases, which contributed to the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

Bison Comeback

How the Comeback Started

In 1887, William Temple Hornaday from the Bronx Zoo wrote a report predicting that bison would be extinct within 20 years. In 1905, he started the American Bison Society with support from Theodore Roosevelt to create and protect bison sanctuaries. Some important early bison conservationists included:

James "Scotty" Philip

James "Scotty" Philip in South Dakota had one of the first herds of bison brought back to North America. In 1899, he bought a small group of five bison. These bison were calves that had been caught in the "Last Big Buffalo Hunt" in 1881. Scotty wanted to save the animal from disappearing. By the time he died in 1911, his herd had grown to about 1,000 to 1,200 bison. Many other private herds started from this group.

Michel Pablo & Charles Allard

In 1873, Samuel Walking Coyote, a member of the Pend d'Oreille tribe, brought seven orphaned bison calves to the Flathead Reservation. In 1899, he sold 13 of these bison to ranchers Charles Allard and Michel Pablo. Pablo and Allard spent over 20 years building one of the largest collections of purebred bison. By 1896, their herd had 300 bison. In 1907, after the U.S. government didn't buy the herd, Pablo sold most of his bison to the Canadian government. They were shipped to the new Elk Island National Park.

Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge

Also in 1907, the Bronx Zoo sent 15 bison to the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge in Oklahoma. This group became the start of a herd that now has 650 bison.

Yellowstone Park

The Yellowstone Park Bison Herd grew naturally from a few bison that survived the mass slaughter in the late 1800s by hiding in Yellowstone National Park. It's the only continuously wild bison herd in the United States. This herd, now numbering between 3,000 and 3,500, came from just 23 bison that survived. In 1902, a captive herd of 21 plains bison was also brought to Yellowstone and managed like livestock until the 1960s. Many national parks, especially Yellowstone, were created partly because people felt bad about the buffalo slaughter.

Antelope Island

The Antelope Island bison herd in Utah started with 12 bison from a private ranch in Texas in the late 1800s. This herd now has between 550 and 700 bison and is one of the largest public herds. It has some special genetic traits and has been used to improve the genetic diversity of American bison.

Molly Goodnight

The last of the "southern herd" in Texas were saved in 1876. Charles Goodnight's wife, Molly, encouraged him to save some of the last bison hiding in the Texas Panhandle. She was so dedicated that she rescued young orphaned buffaloes, bottle-fed them, and cared for them until they were grown. By saving these few plains bison, she started an impressive buffalo herd near the Palo Duro Canyon. This herd, known as the Goodnight herd, reached 250 bison in 1933. Their descendants were moved to Caprock Canyons State Park and Trailway in 1998.

Austin Corbin

In 1904, naturalist Ernest Harold Baynes was put in charge of the Corbin Park buffalo reserve in New Hampshire. This park was a hunting club with 26,000 acres. Austin Corbin Sr., a banker, had imported bison from many states and Canada and donated them to other zoos. He also brought in other animals like wild boar. From an original 60 million bison in America, the population had dropped to just 1,000 by the 1890s. In 1904, 160 of these lived in Corbin Park. Baynes was known for his tame bison and for driving a carriage pulled by two bison!

Modern Bison Comeback Efforts

Many other bison herds are being created in state parks, national parks, and on private ranches. These herds often start with bison from the main "foundation herds." For example, the Henry Mountains bison herd in Utah started in 1941 with bison from Yellowstone National Park. This herd now has about 400 bison.

One of the largest private herds, with 2,500 bison, is at the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in Oklahoma. Ted Turner is the largest private owner of bison, with about 50,000 on his ranches.

The American bison population is growing fast, now estimated at 350,000. This is much better than the fewer than 100 in the late 1800s, but still far from the estimated 60 to 100 million that once roamed. Most current herds, however, have some genes from domestic cattle mixed in. Today, there are only four truly wild, public bison herds that are also free of a disease called brucellosis: the Henry Mountains Bison Herd and the Wind Cave bison herd.

The presence of wild bison in Montana is sometimes seen as a threat by cattle ranchers. They worry that bison carrying brucellosis might infect their cattle. However, there has never been a proven case of brucellosis spreading from wild bison to cattle.

Native American Bison Conservation

Native American tribes have also made many efforts to save and grow the bison population. The Inter Tribal Bison Council was formed in 1990, with 56 tribes in 19 states. These tribes manage over 15,000 bison. They focus on bringing bison back to tribal lands to promote their culture, bring back spiritual connections, and restore the ecosystem. Some members believe that the bison's economic value is a main reason for its comeback. Bison are a cheaper alternative to cattle and can handle harsh winters better.

Another Native American conservation effort is the Buffalo Field Campaign, started in 1996. They want bison to be able to roam freely in Montana and beyond. They challenge officials who kill bison that wander outside Yellowstone National Park in search of food.

Many smaller tribal groups also want to bring bison back to their native lands. The Ponca Tribe of Nebraska, for example, has about 100 bison. The Southern Ute Tribe in Colorado has nearly 30 bison.

Bringing bison back can lead to better meat and a healthier environment. It also helps restore the relationship between bison and Native Americans. However, there is a risk of brucellosis if many bison are introduced.

Bison Conservation: A Symbol of Healing

For some, the comeback of the bison population shows a cultural and spiritual recovery from the effects of bison hunting in the mid-1800s. By creating groups like the Inter-Tribal Bison Cooperative, Native Americans hope to restore the bison population and improve unity and morale among their tribes. Fred Dubray, a former president of the Inter-Tribal Bison Cooperative, said, "We recognize the bison as a symbol of strength in unity... To reestablish healthy buffalo populations is to reestablish hope for Indian people."

Bison Hunting Today

Hunting wild bison is allowed in some states and provinces where public herds need to be managed to keep their population at a certain level. In Alberta, Canada, where one of only two continuously wild bison herds in North America lives at Wood Buffalo National Park, bison are hunted to protect other disease-free herds.

Montana

In Montana, public bison hunting was brought back in 2005, with 50 permits given out. In 2006/2007, the number of permits increased to 140. Some groups argue that it's too early to allow hunting, given that bison still need more habitat and protection in Montana.

Hundreds, and sometimes over a thousand, bison from the Yellowstone Park Bison Herd are killed each year when they wander north from Yellowstone National Park into private and state lands in Montana. This hunting happens because people worry that the Yellowstone bison, which often carry brucellosis, will spread the disease to local cattle. However, there has never been a proven case of brucellosis spreading from wild bison to cattle.

Utah

The State of Utah manages two bison herds. Bison hunting is allowed for both the Antelope Island bison herd and the Henry Mountains bison herd, but licenses are limited and carefully controlled. A Game Ranger usually goes with hunters to help them find and choose the right bison to kill. This way, hunting is used to manage the wildlife and remove less desirable individuals.

Every year, all the bison in the Antelope Island bison herd are rounded up for check-ups and vaccinations. Most are then released, but about 100 bison are sold at an auction, and a few are allowed to be hunted. This hunting takes place on Antelope Island in December each year. The money from these hunts helps improve Antelope Island State Park and maintain the bison herd.

Hunting is also allowed every year in the Henry Mountains bison herd in Utah. This herd sometimes has up to 500 bison, but the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources has decided that the area can only support 325. Some extra bison are moved to other places, but most are not, so hunting is the main way to control their population. In 2009, 146 permits were given out for hunting bison in the Henry Mountains. Most years, 50 to 100 licenses are issued.

Alaska

Bison were also brought back to Alaska in 1928. Both domestic and wild herds live in some parts of the state. Alaska gives out a limited number of permits to hunt wild bison each year.

Mexico

In 2001, the United States government gave some bison calves from South Dakota and Colorado to the Mexican government. This was to reintroduce bison to Mexico's nature reserves, including areas like El Uno Ranch in Chihuahua and Boquillas del Carmen in Coahuila, which are near the border with Texas and New Mexico.

Images for kids

-

Lakota winter count of American Horse, 1817–1818. This shows a time of plenty of buffalo meat.

-

Ulm Pishkun. A Blackfoot buffalo jump in Montana.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |