William Temple Hornaday facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Temple Hornaday

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

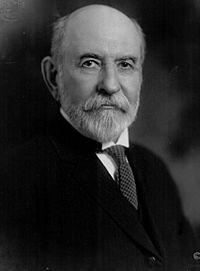

| Born | December 1, 1854 |

| Died | March 6, 1937 (aged 82) |

| Resting place | Greenwich, Connecticut |

| Occupation | Zoologist |

| Spouse(s) | Josephine Chamberlain |

| Parent(s) | William Temple Hornaday, Sr. Martha Hornaday (née Martha Varner) |

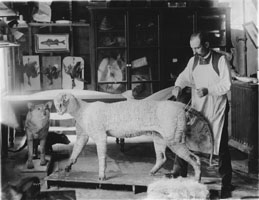

William Temple Hornaday (December 1, 1854 – March 6, 1937) was an American zoologist, someone who studies animals. He was also a conservationist, working to protect nature and wildlife. Hornaday was a skilled taxidermist, meaning he prepared, stuffed, and mounted animal skins to make them look alive. He was also an author.

He became the first director of the New York Zoological Park, which you might know today as the Bronx Zoo. He was a very important person in the early efforts to protect wildlife in the United States.

Contents

Early Life and Career

William Hornaday was born in Avon, Indiana. He studied at Oskaloosa College and Iowa State University. He also studied in Europe.

After his studies, Hornaday worked as a taxidermist at a science center in Rochester, New York. He then spent a year and a half, from 1877 to 1878, traveling in India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). He collected many animal specimens there. In 1878, he also visited Malaya and Sarawak in Borneo. His adventures inspired his first book, Two Years in the Jungle, published in 1885.

In 1882, he became the chief taxidermist at the United States National Museum. He worked there until 1890.

Protecting the American Bison

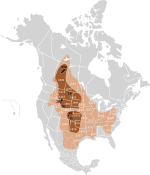

At the museum, Hornaday was asked to check how many American Buffalo specimens they had. He found they had very few. He then decided to count the wild bison by writing to people across the American West and Canada.

He learned that in 1867, there were about 15 million wild bison. But by the time he did his count, their numbers had dropped very quickly. He reported that the large herds of buffalo in the United States were almost gone.

In 1886, Hornaday traveled to Montana, where the last wild American buffalo herds lived. He was supposed to collect specimens for the museum. This was so future generations would know what buffalo looked like, as people expected them to become extinct.

The buffalo that Hornaday prepared for display stayed in the museum until the 1950s. Later, they were restored and put on display again in 1996 in Fort Benton, Montana.

Seeing how quickly the buffalo were disappearing changed Hornaday. He became a strong conservationist. He brought live buffalo back to Washington, D.C. These animals started the Department of Living Animals at the Smithsonian. This department later became the National Zoological Park, which Hornaday helped create in 1889. He was the zoo's first director but left soon after due to disagreements.

Leading the Bronx Zoo

In 1896, the New York Zoological Society asked Hornaday to help create a new, amazing zoo. This zoo is now known as the Bronx Zoo. Hornaday played a big role in choosing the location and designing the early animal exhibits. The zoo opened in 1899.

He worked as the Director, General Curator, and Curator of Mammals. He helped build one of the world's largest animal collections. He also made sure that animal exhibits had clear labels and encouraged talks about wildlife. He even offered space for wildlife artists to work. Hornaday retired in 1926.

A Difficult Time at the Zoo

In September 1906, during Dr. Hornaday's time as director, there was a big controversy. A man named Ota Benga, from the Congo, was put on display in the monkey house. He would shoot targets with a bow and arrow and wrestle with an orangutan.

Some people did not object to seeing a human in a cage with monkeys. However, black religious leaders in the city were very upset. They felt it was wrong to display a human being like an animal. Reverend James H. Gordon said, "Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes." He added, "We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls."

New York Mayor George B. McClellan, Jr. refused to meet with the clergymen. Dr. Hornaday praised the mayor for this. He called the event "its most amusing passage" in the zoo's history.

As the arguments continued, Hornaday still said his only goal was to create an "ethnological exhibit." This means he wanted to show different human cultures. He believed the zoo should not be told what to do by the clergymen.

However, Hornaday decided to close the exhibit after only two days. On September 8, Benga was allowed to walk freely around the zoo grounds. But crowds often followed him, making noise and yelling.

Wildlife Conservation Efforts

Hornaday became a strong supporter of saving the American bison from extinction. In the late 1800s, he started planning a group to protect bison, with help from President Theodore Roosevelt.

Later, as director of the Bronx Zoo, Hornaday got more bison. By 1903, there were forty bison at the zoo. In 1905, the American Bison Society was formed at the Bronx Zoo, and Hornaday became its president. When the first large game preserve in America was created in 1905, Hornaday offered fifteen bison from the Bronx Zoo to help reintroduce them to the wild. He chose the release site and the animals himself. By 1919, nine bison herds had been started in the U.S. thanks to the American Bison Society.

During his life, Hornaday wrote almost two dozen books and hundreds of articles about the importance of conservation. He often said that protecting wildlife was a moral duty. His most famous book was Our Vanishing Wildlife: Its Extermination and Preservation, published in 1913. He sent a copy to every member of Congress. This book was a powerful call to action against overhunting.

Hornaday wanted readers to feel emotional about the animals. He wrote that "birds and mammals now are literally dying for your help." He wasn't completely against hunting. However, he became more and more worried about how modern hunting, with new guns and cars, was harming animal populations. He strongly believed that people who didn't hunt should stop those who hunted too much.

Throughout his career, he worked hard to get new laws passed to protect wildlife. He spoke to Congress and helped create the Permanent Wild Life Protection Fund in 1913. This fund helped pay for his efforts to get conservation laws passed. He worked with a network of conservation activists across the United States. He pushed for protective laws, national parks, wildlife refuges, and international agreements. By 1915, a journal said that Hornaday had started and succeeded in more efforts to protect wild animals than anyone else in America.

His Impact on Scouting

Hornaday had a big influence on the Scouting movement, especially the Boy Scouts of America (BSA). There was even a series of conservation awards named after him. His ideas and writings were a main reason why conservation and ecology became important parts of the BSA's program.

Hornaday created this awards program in 1915. He called it the Wildlife Protection Medal. Its goal was to encourage Americans to work for wildlife conservation and protect animal homes. After he died in 1938, the award was renamed in his honor and became a BSA award. However, in October 2020, the BSA changed the name of the award to the BSA Distinguished Conservation Service Award. They felt that some of Hornaday's past actions went against the BSA's values of fighting racism and discrimination.

Personal Life

Hornaday married Josephine Chamberlain in 1879. They were married for 58 years until he passed away. They had one daughter named Helen. Hornaday died in Stamford, Connecticut, and was buried in Putnam Cemetery in Greenwich, Connecticut.

A year after his death, in 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt suggested naming a mountain after him. This mountain, Mount Hornaday, is in Yellowstone National Park.

Select Books by Hornaday

- Two Years in the Jungle (1885)

- Free Run on the Congo (1887)

- The Extermination of the American Bison (1889)

- Taxidermy and Zoölogical Collecting (1891)

- The Man Who Became a Savage (1896)

- Guide to the New York Zoölogical Park (1899)

- The American Natural History (1904)

- Campfires in the Canadian Rockies (1906)

- Popular Official Guide to the New York Zoological Park: https://archive.org/details/cu31924031278264 (1909)

- Our Vanishing Wild Life (1913)

- Wild Life Conservation in Theory and Practice (1914)

- The Lying Lure of Bolshevism (1919)

- The Minds and Manners of Wild Animals; A Book of Personal Observations (1922)

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |