Ota Benga facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ota Benga

|

|

|---|---|

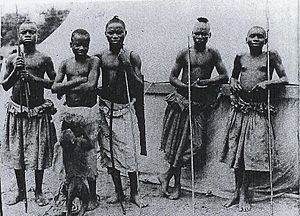

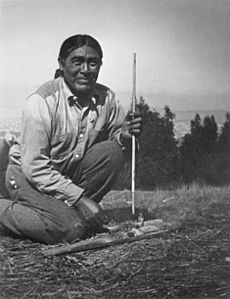

Benga at the St. Louis World's Fair, 1904

|

|

| Born |

Mbye Otabenga

c. 1883 |

| Died | (aged 32–33) Lynchburg, Virginia, U.S.

|

| Resting place | White Rock Cemetery, Lynchburg, Virginia |

| Height | 4 ft 11 in (150 cm) |

| Children | 2 |

Ota Benga (born around 1883 – died March 20, 1916) was a man from the Mbuti group in Central Africa. He became known for being put on display at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri. Later, in 1906, he was also displayed at the Bronx Zoo in New York.

An explorer named Samuel Phillips Verner brought Benga to the United States. Verner had bought Benga from slave traders in Africa. At the Bronx Zoo, Benga was allowed to walk around the grounds. But he was also put in a cage with an orangutan. This was done to make him seem more "primitive." He was given a bow and arrow. Benga used it to shoot at visitors who made fun of him. This helped end his display at the zoo.

After the St. Louis Fair, Benga briefly visited Africa with Verner. But he spent most of his life in the United States, mainly in Virginia. Many African-American newspapers spoke out against how Benga was treated. Black church leaders asked the mayor of New York City to free him from the zoo. In late 1906, Benga was released to James H. Gordon. Gordon ran the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn.

In 1910, Gordon helped Benga move to Lynchburg, Virginia. There, his pointed teeth were covered to help him fit in better. Benga learned English and worked in a tobacco factory. He hoped to return to Africa, but World War I started in 1914. This stopped all passenger ship travel.

Contents

Ota Benga's Early Life

Ota Benga was a member of the Mbuti people. They lived in the forests near the Kasai River in what was then called the Congo Free State. His village was attacked by the Force Publique. This was a group created by King Leopold II of Belgium. They forced local people to work collecting rubber.

Benga's wife and two children were killed in the attack. He survived because he was away hunting. Later, he was captured by slave traders from another tribe.

In 1904, an American businessman named Samuel Phillips Verner went to Africa. He was hired by the St. Louis World Fair. His job was to find and bring African people for an exhibit. Verner found Benga while traveling. He bought Benga from the slave traders. He traded a pound of salt and a piece of cloth for him. Verner later said he had saved Benga from cannibals.

Verner and Benga spent several weeks together. They then reached a Batwa pygmy village. The villagers did not trust white people. Verner could not convince anyone to go to the United States. But Benga spoke up. He said Verner had saved his life. He also talked about his own interest in Verner's world. Four Batwa men decided to go with them. Verner also recruited other Africans. These included five men from the Bakuba people.

Exhibitions and Displays

St. Louis World Fair Display

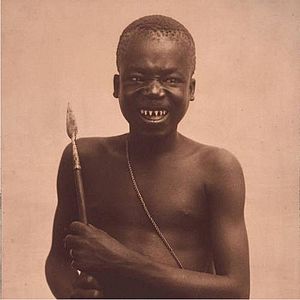

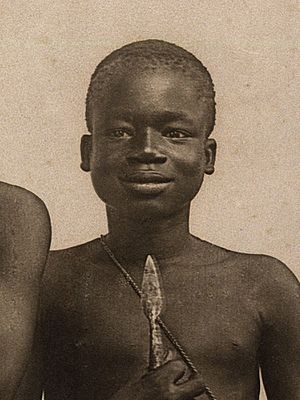

The group arrived in St. Louis, Missouri, in June 1904. Verner was not with them because he was sick with malaria. The World's Fair had already started. The Africans quickly became very popular. Benga was especially well-known. Newspapers called him by different names. He was friendly, and visitors wanted to see his teeth. His teeth had been filed to sharp points as a ritual when he was young.

The Africans learned to charge money for photos and performances. One newspaper called Benga "the only real African cannibal in America." It said his teeth were "worth the five cents he charges for showing them."

When Verner arrived a month later, he saw the pygmies were more like prisoners. Crowds would bother them even when they tried to gather peacefully. The fair organizers wanted to show them as "savages." On July 28, 1904, a large crowd gathered. Soldiers had to be called to control them. Benga and the other Africans began to act like the Native Americans they saw at the fair. The Apache chief Geronimo admired Benga. He even gave Benga one of his arrowheads.

American Museum of Natural History

Benga went with Verner when he took the other Africans back to the Congo. Benga lived with the Batwa for a short time. He also went on other trips with Verner in Africa. He married a Batwa woman, but she died from a snakebite. Not feeling like he belonged, Benga chose to return to the United States with Verner.

Verner arranged for Benga to stay at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Benga was given a suit to wear when he met people. He enjoyed his time there at first. But soon, he missed his own culture.

It was hard for him to be inside all the time. He felt like he was a stuffed exhibit behind glass. He missed the sounds of birds, breezes, and trees.

Benga became unhappy. He tried to sneak past guards when crowds left. Once, he was asked to seat a rich visitor's wife. He pretended not to understand. Instead, he threw the chair across the room, nearly hitting her. Meanwhile, Verner was having money problems. He found another place for Benga to stay.

Bronx Zoo Display

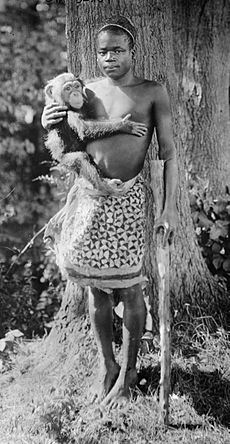

Verner took Benga to the Bronx Zoo in 1906. The zoo director, William Hornaday, first hired Benga to help with the animal areas. But Hornaday noticed that people paid more attention to Benga than the animals. So, he decided to make Benga an exhibit. Benga was allowed to walk around the zoo grounds. But he was never paid for his work. He became friends with an orangutan named Dohong.

Benga started spending time in the Monkey House exhibit. The zoo encouraged him to hang his hammock there. They also had him shoot his bow and arrow at a target. On September 8, 1906, visitors found Benga in the Monkey House.

Soon, a sign was put on the exhibit. It read: "The African Pygmy, 'Ota Benga.'

Age, 23 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches.

Weight, 103 pounds. Brought from the

Kasai River, Congo Free State, South Cen-

tral Africa, by Dr. Samuel P. Verner. Ex-

hibited each afternoon during September."

Hornaday thought the exhibit was a good show for visitors. Madison Grant, a leader of the New York Zoological Society, supported him. Grant later became known for his ideas about racial differences.

African-American clergymen quickly spoke out against the exhibit. James H. Gordon said, "Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes... We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls."

Gordon believed the exhibit was against Christianity. He felt it promoted Darwinism, which he opposed. Many other clergymen agreed with Gordon.

However, an article in The New York Times disagreed. It said, "It is absurd to make moan over the imagined humiliation and degradation Benga is suffering. The pygmies... are very low in the human scale." It also said Benga would not benefit from school.

Because of the protests, Benga was allowed to roam the zoo grounds. But he became more mischievous and sometimes violent. This was partly due to the crowds bothering him. An article quoted Robert Stuart MacArthur saying, "It is too bad that there is not some society like the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. We send our missionaries to Africa to Christianize the people, and then we bring one here to brutalize him."

The zoo finally removed Benga from the grounds. Verner could not find a job, but he still talked to Benga. They both agreed it was best for Benga to stay in the United States. In late 1906, Benga was given to Reverend Gordon.

Later Life in Virginia

Gordon placed Benga in the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum. This was an orphanage in Brooklyn that Gordon managed. The unwanted attention from the press continued. So, in January 1910, Gordon moved Benga to Lynchburg, Virginia. He lived with the family of Gregory W. Hayes.

To help him fit into society, Gordon arranged for Benga's pointed teeth to be covered. He also bought him American-style clothes. Benga received lessons from a poet named Anne Spencer. This helped him improve his English. He also started elementary school at the Baptist Seminary in Lynchburg.

Once he felt his English was good enough, Benga stopped formal schooling. He began working at a Lynchburg tobacco factory. He started making plans to return to Africa.

Death

In 1914, World War I began. This made it impossible for passenger ships to travel. Benga became very sad as his hopes of returning home faded.

Benga was buried in an unmarked grave. It was in the black section of the Old City Cemetery. His friend, Gregory Hayes, was buried nearby. Later, the remains of both men went missing. Local stories say they were moved to White Rock Hill Cemetery. This cemetery later fell into disrepair. In 2017, a historic marker for Benga was placed in Lynchburg.

Ota Benga's Legacy

Phillips Verner Bradford, the grandson of Samuel Phillips Verner, wrote a book about Benga. It was called Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo (1992). While researching, Bradford visited the American Museum of Natural History. They have a life mask and body cast of Ota Benga. This display is still labeled "Pygmy," not with Benga's name. People have objected to this for over a century.

Bradford's book in 1992 brought a lot of attention to Ota Benga's story. It led to many other works, both true stories and made-up ones. Some of these include:

- 1994 – John Strand's play, Ota Benga, was performed in Arlington, Virginia.

- 1997 – The play, Ota Benga, Elegy for the Elephant, by Dr. Ben B. Halm, was staged in Connecticut.

- 2002 – A short film called Ota Benga: A Pygmy in America was made. It used old movies recorded by Verner.

- 2005 – A movie called Man to Man told a made-up version of his life.

- 2006 – The band Piñataland released a song about Ota Benga called "Ota Benga's Name."

- 2007 – Poems about Benga were turned into a performance.

- 2008 – Benga inspired a character in the movie The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

- 2010 – The band May Day Orchestra made a music album inspired by Ota Benga's story.

- 2011 – The Italian band Mamuthones recorded a song called "Ota Benga."

- 2012 – A poetry book, Ota Benga Under My Mother's Roof, was published. It was by Carrie Allen McCray, whose family had cared for Benga.

- 2012 – Ota Benga the Documentary Film was released.

- 2015 – Journalist Pamela Newkirk published a book about Benga called Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga.

- 2016 – The Radio Diaries podcast told Benga's story in "The Man in the Zoo."

- 2019 – The University of Alabama at Birmingham created a musical called Savage based on Benga's story.

- 2019 – A play called A Human Being, of a Sort, based on Benga's story, was performed.

- 2020 – The Wildlife Conservation Society, which runs the Bronx Zoo, apologized for how Benga was treated. They also apologized for promoting ideas about racial superiority.

Similar Cases

Some people have compared Ota Benga's story to that of Ishi. Ishi was the last member of the Yahi Native American tribe. He was also put on display in California around the same time. Ishi died on March 25, 1916, just five days after Ota Benga.

See also

In Spanish: Ota Benga para niños

In Spanish: Ota Benga para niños

- Saartjie Baartman, also known as the "Hottentot Venus," who was also put on display.

- Human zoo

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |