Omaha people facts for kids

| Umoⁿhoⁿ | |

|---|---|

Flag of the Omaha Tribe of Nebraska and Iowa

|

|

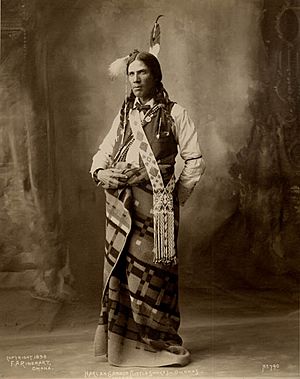

Omaha tribal dancer

|

|

| Total population | |

| 6,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Omaha-Ponca | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, other | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Siouan and Dhegihan peoples, esp. Ponca, Otoe, Osage, Iowa |

The Omaha (in their own language, Umoⁿhoⁿ) are an officially recognized Native American tribe. They live on their own land called the Omaha Reservation. This land is mostly in northeastern Nebraska and western Iowa, United States. The reservation covers about 796 square kilometers (307 square miles). In 2000, about 5,194 people lived there. The largest town on the reservation is Macy.

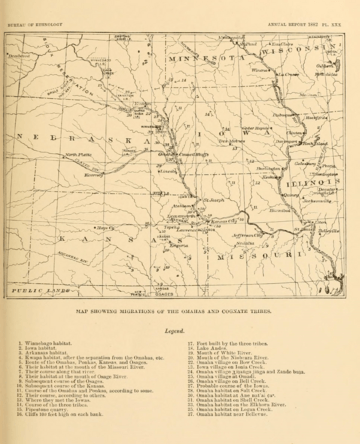

The Omaha people moved to the upper Missouri River area and the Plains by the late 1600s. They came from earlier homes in the Ohio River Valley. The Omaha speak a Siouan language. This language is very similar to the one spoken by the Ponca tribe. The Ponca were once part of the Omaha tribe. They separated in the mid-1700s. The Omaha were also related to other Siouan-speaking groups. These include the Osage, Quapaw, and Kansa peoples. These tribes also moved west because of pressure from the Iroquois tribe.

Around 1770, the Omaha became the first tribe on the Northern Plains to use horses. They developed a large village called "The Big Village" (Ton-wa-tonga) around 1775. This village was in what is now Dakota County. The Omaha created a wide trading network with early European explorers and French Canadian traders. They controlled the fur trade and access to other tribes on the Upper Missouri River.

The city of Omaha, Nebraska is named after them. The Omaha tribe never fought against the United States. They even helped the U.S. during the American Civil War.

Contents

History of the Omaha People

The Omaha tribe started as a larger Woodland tribe. This group included both the Omaha and Quapaw tribes. Around the year 1600, they lived near the Ohio River and Wabash rivers. As the tribe moved west, it split into the Omaha and Quapaw tribes. The Quapaw settled in what is now Arkansas. The Omaha, whose name U-Mo'n-Ho'n means "upstream," settled near the Missouri River. This was in what is now northwestern Iowa.

Another split happened later, and the Ponca became their own tribe. However, they often lived near the Omaha. The first time Europeans wrote about the Omaha tribe was in 1700. A French explorer named Pierre-Charles Le Sueur described an Omaha village. It had 400 homes and about 4,000 people. This village was near the Big Sioux River and the Missouri River. Today, this area is near Sioux City, Iowa. The French called it "The River of the Mahas."

In 1718, a French mapmaker named Guillaume Delisle mapped the tribe. He called them "The Maha, a wandering nation." They were shown along the northern part of the Missouri River. French fur traders found the Omaha on the east side of the Missouri River in the mid-1700s. The Omaha were thought to have lived from the Cheyenne River in South Dakota to the Platte River in Nebraska. Around 1734, the Omaha built their first village west of the Missouri River. This was on Bow Creek in today's Cedar County, Nebraska.

Around 1775, the Omaha built a new village. It was likely near today's Homer, Nebraska. This village was called Ton won tonga (or Tonwantonga), meaning "Big Village." It was the village of Chief Blackbird. At this time, the Omaha controlled the fur trade on the Missouri River. Around 1795, the village had about 1,100 people.

Around 1800, a smallpox sickness spread through the area. This disease came from contact with Europeans. It greatly reduced the tribe's population, killing about one-third of its members. Chief Blackbird was one of those who died that year. Blackbird had traded with the Spanish and French. He used trade to protect his people. He knew his tribe was not large enough to defend itself from other tribes. So, he believed that good relations with white explorers and trading were key to their survival. The Spanish built a fort nearby and often traded with the Omaha during this time.

After the United States bought the Louisiana Purchase, more goods came to the Omaha. Tools and clothing became common, like scissors, axes, and buttons. Women started making more goods for trade. They also did more farming, perhaps because of new tools. Women buried after 1800 had harder, shorter lives. None lived past age 30. But they also had bigger roles in the tribe's economy. Scientists found that later women's skeletons were buried with more silver items than men's or women's before 1800. After the research, the tribe reburied these ancestors in 1991.

When Lewis and Clark visited Ton-wa-tonga in 1804, most people were away. They were on a seasonal buffalo hunt. The explorers met with the Otoe people, who also spoke a Siouan language. The explorers were led to Chief Blackbird's burial site. In 1815, the Omaha signed their first treaty with the United States. It was a "treaty of friendship and peace." The tribe did not give up any land.

Omaha villages usually lasted 8 to 15 years. They built sod houses for winter homes. These were arranged in a large circle. The homes were placed in the order of the five clans of each half of the tribe. This kept the balance between the Sky and Earth parts of the tribe. Later, sickness and attacks from the Sioux tribe forced the Omaha to move south. Between 1819 and 1856, they built villages near what is now Bellevue, Nebraska. They also built villages along Papillion Creek.

Giving Up Land

In 1831, the Omaha gave up their lands in Iowa to the United States. These lands were east of the Missouri River. They understood that they could still hunt there. In 1836, another treaty with the U.S. took their remaining hunting lands in northwestern Missouri.

During the 1840s, the Omaha continued to suffer from Sioux attacks. European-American settlers wanted the U.S. government to make more land available. In 1846, Big Elk made an agreement allowing a large group of Mormons to settle on Omaha land. He hoped their guns would offer some protection from other tribes. But the new settlers used up a lot of the game and wood in the area.

For almost 15 years in the 1800s, Logan Fontenelle worked as an interpreter. He worked at the Bellevue Agency for different U.S. Indian agents. He was part Omaha and part French. He spoke three languages and also worked as a trader. In January 1854, he helped with land talks. Sixty Omaha leaders met with agent James M. Gatewood. The Omaha leaders agreed to sell most of their remaining lands west of the Missouri River to the United States.

Seven chiefs went to Washington, D.C., for the final talks. Logan Fontenelle went as their interpreter. The chief Iron Eye (Joseph LaFlesche) was one of these seven. He is seen as the last chief of the Omaha under their old system. White people mistakenly thought Logan Fontenelle was a chief. But because his father was white, the Omaha did not see him as a tribe member. They considered him white.

The tribe moved to the Blackbird Hills around 1856. They first built a village in their traditional circular pattern. By the 1870s, buffalo were quickly disappearing. The Omaha had to rely more on money from the U.S. government. They also started farming more. Jacob Vore, a Quaker, became the U.S. Indian agent for the Omaha Reservation in 1876.

That year, Vore gave out less money to the tribe. He did this just before the Omaha left for their annual buffalo hunt. He wanted to encourage them to farm more. They had a bad hunting season and a harsh winter. Some people were starving by late spring. Vore got more money for them. But for the rest of his time as agent, he did not give out the $20,000 cash they were supposed to get each year. Instead, he gave them tools for farming. He told the tribe that Washington, D.C., officials had stopped the money. The people had no choice. They worked hard to grow more food, increasing their harvest to 20,000 bushels.

The Omaha never fought against the U.S. Several tribe members fought for the Union during the American Civil War. They have also fought in every war since then.

In the 1960s, the Omaha began to get back lands east of the Missouri River. This area is called Blackbird Bend. After many court cases, much of the area is now recognized as Omaha tribal land. The Omaha built their Blackbird Bend Casino on this land.

Learning from the Past

In 1989, the Omaha got back over 100 skeletons of their ancestors. These were from Ton-wo-tonga. Museums had kept them. Scientists had dug them up in the 1930s and 1940s. They were from burial sites before and after 1800. Before reburying the remains, the tribe let researchers study them. This was done at the University of Nebraska.

Researchers found big differences in the community before and after 1800. This was seen in their bones and items buried with them. Most importantly, they learned that the Omaha were horse riders and buffalo hunters by 1770. This made them the first horse-riding culture known on the Northern Plains. They also found that before 1800, the Omaha mainly traded weapons and jewelry. Men had more roles in the tribe than women. They were "archers, warriors, gunsmiths, and merchants." They also had important religious roles. Sacred bundles from religious ceremonies were only found buried with men.

Omaha Culture and Traditions

In earlier times, the Omaha had a very detailed social structure. It was linked to their belief that the sky (male) and earth (female) were connected. This was part of their creation story and how they saw the world. This connection was important for all life. The tribe was split into two halves: the Sky People (Insta'shunda) and the Earth People (Hon'gashenu). Each half had a different chief.

Sky people were in charge of the tribe's spiritual needs. Earth people were in charge of the tribe's physical well-being. Each half had five clans. These clans also had different duties. Each clan had a chief. Children belonged to their father's clan. People married someone from a different clan.

These chiefs and clan structures still existed when the Omaha leaders talked with the United States. They agreed to give up most of their land in Nebraska. In return, they got protection and money. Only men born into these family lines could become chiefs. Or, they could be formally adopted by a man into the tribe. Joseph LaFlesche (Iron Eye) was adopted by the chief Big Elk in the 1840s. Big Elk chose LaFlesche to be his son and the next chief. LaFlesche was of mixed race. He was the last head chief chosen in the old ways. He was also the only chief with any European family. He served for many years starting in 1853.

Even though white people thought Logan Fontenelle was a chief, the Omaha did not. They used him as an interpreter. He was of mixed race with a white father. So, he was seen as white, since he had not been adopted by a man of the tribe.

Today, the Omaha hold an annual pow wow. At this celebration, a committee chooses the Omaha Pow Wow Princess. She represents the community and is a role model for younger children.

Homes and Villages

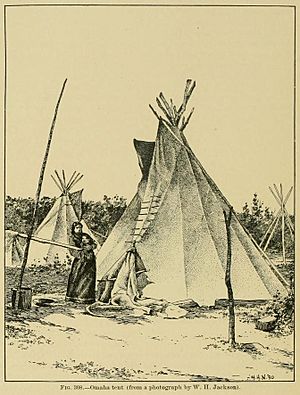

As the tribe moved west from the Ohio River area in the 1600s, they learned to live on the Plains. They stopped using bark lodges. Instead, they used tipis (like the Sioux) for buffalo hunting and summer. They built earth lodges (like the Arikara) for winter. Tipis were mainly used during buffalo hunts and when moving between villages. Earth lodges were their homes in winter.

Omaha beliefs were shown in their homes. For most of the year, the Omaha lived in earth lodges. These were clever structures with a wood frame and a thick dirt covering. In the center of the lodge was a fireplace. This reminded them of their creation story. The entrance of the earth lodge faced east. This was to catch the rising sun and remind people of their origins and journey from the east.

The Huthuga, which was the circular shape of their villages, showed the tribe's beliefs. Sky people lived in the northern half-circle of the village. This area stood for the heavens. Earth people lived in the southern half. This part stood for the earth. The circle opened to the east. Within each half of the village, the clans were placed based on their duties and how they related to other clans. Earth lodges could be as large as 18 meters (60 feet) across. They could hold several families, and even their horses.

When the tribe moved to the Omaha Reservation around 1856, they first built their village and earth lodges in the traditional circular patterns. The two halves of the tribe and the clans were in their usual places.

Spiritual Beliefs

The Omaha respect an old Sacred Pole. It is from before their move to the Missouri River. It is made of cottonwood wood. It is called Umoⁿ'hoⁿ'ti, which means "The Real Omaha." It is thought of as a person. It was kept in a Sacred Tent in the middle of the village. Only men who were part of the Holy Society could go inside. An annual ceremony was held to renew the Sacred Pole.

In 1888, Francis La Flesche, a young Omaha anthropologist, helped his friend Alice Fletcher. They arranged for the Sacred Pole to go to the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University. This was to protect it and its stories. At that time, the tribe's way of life seemed to be in danger. The tribe was thinking about burying the Pole with its last keeper after he died. The last renewal ceremony for the pole was in 1875. The last buffalo hunt was in 1876. La Flesche and Fletcher collected stories about the Sacred Pole. They got them from its last keeper, Yellow Smoke, a holy man of the Hong'a clan.

In the 1900s, about 100 years later, the tribe talked with the Peabody Museum to get the Pole back. The tribe planned to put the Sacred Pole in a new cultural center. When the museum returned the Sacred Pole in July 1989, the Omaha held a pow-wow in August. This was a celebration and part of their cultural revival.

The Sacred Pole is said to represent a man's body. Its name, a-kon-da-bpa, is the word for the leather bracer worn on the wrist. This bracer protects from the bow string when using a bow and arrow. This name shows that the pole stood for a man. Only a man could wear a bracer. It also meant that the man it stood for was someone who provided for and protected his people.

Films About the Omaha

- 1990 – The Return of the Sacred Pole. This film was made by Michael Farrell. It was produced by KUON-TV.

- 2019 – The Omaha Speaking. This film was directed by Brigitte Timmerman. Tatanka Means tells the story.

Omaha Communities

Famous Omaha People

- Blackbird, a chief

- Big Elk (1770–1846/1853), a chief who adopted Joseph LaFlesche

- Francis M. Cayou, a football coach

- Logan Fontenelle (1825–1855), an interpreter

- Rodney A. Grant (born 1959), an actor

- Joseph LaFlesche (Iron Eye, about 1820—1888), a chief with European family, the last traditional chief

- Francis La Flesche (1857–1932), the first Native American ethnologist (someone who studies cultures)

- Susan La Flesche Picotte (1865–1915), the first female Native American doctor

- Susette LaFlesche Tibbles (1854–1903), an author and activist for Native American rights

- Jeremiah Bitsui, an actor

- Thomas L. Sloan (1863–1940), the first Native American lawyer to argue a case in the U.S. Supreme Court

- Hiram Chase (1861–1928), with Thomas L. Sloan, formed the first Native American law firm in the U.S.

- Nathan Phillips (born 1954), a Native American activist

See also

In Spanish: Pueblo omaha para niños

In Spanish: Pueblo omaha para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |