Osage Nation facts for kids

The Osage Nation (pronounced OH-sayj), whose own name means "People of the Middle Waters," is a Native American tribe from the Great Plains region of the United States. Their ancestors lived in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys around 700 B.C. Over time, they moved west, settling near the Missouri and Mississippi rivers.

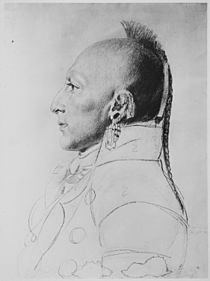

The name "Osage" comes from a French word meaning "calm water." The Osage people call themselves Wazhazhe, meaning "Mid-waters." By the early 1800s, the Osage were very powerful in their region. They controlled a large area between the Missouri and Red rivers, from the Ozarks to the Wichita Mountains. They were skilled hunters of buffalo and also farmed. People described the Osage as tall and brave warriors. They were related to other Siouan-speaking tribes like the Kansa, Ponca, Omaha, and Quapaw.

In the 1800s, the United States government forced the Osage to move from Kansas to what is now Oklahoma. Most Osage people live there today. In the early 1900s, oil was found on their land. The Osage had kept the rights to the minerals under their land, so many became very wealthy from oil royalties. However, this wealth also brought challenges, including fraud and unfair treatment from outsiders. In 2011, after a long legal fight, the Osage Nation received a large settlement from the U.S. government because of past mismanagement of their oil funds. Today, the Osage Nation is a federally recognized tribe with about 20,000 members. Many live in Oklahoma, but others live across the country.

Quick facts for kids

The Osage Nation

Ni Okašką

(People of the Middle Waters) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

Osage Nation government buildings, Pawhuska

|

|||

|

|||

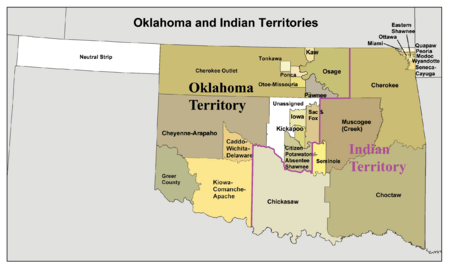

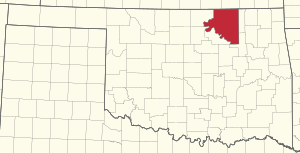

Location of the Osage Reservation in Oklahoma

|

|||

| Tribe | Osage Nation | ||

| Country | United States | ||

| State | Oklahoma | ||

| County | Osage | ||

| Headtown | Pawhuska | ||

| Government | |||

| • Body | Federally recognized tribe | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 2,200 sq mi (6,000 km2) | ||

| Population

(2017)

|

|||

| • Total | 47,350 | ||

| • Density | 21.5/sq mi (8.31/km2) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Siouan | ||

| Time zone | UTC-6 | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (central) | ||

| Website | osagenation-nsn.gov | ||

| This article contains Osage Unicode characters. Without the correct software, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Osage letters. |

| 𐓁𐒻 𐓂𐒼𐒰𐓇𐒼𐒰͘ Ni Okašką |

|

|---|---|

Flag of the Osage Nation of Oklahoma

|

|

| Total population | |

| 24,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States historically Missouri, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Kansas. The majority of Osage citizens still live in Oklahoma, but many others live and work in different American states. | |

| Languages | |

| Osage, English, French | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional Spirituality, Inlonshka, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Siouan peoples, Dhegihan peoples esp. Ponca, Otoe, Iowa, Kansa, Quapaw, Dakota, Omaha |

Contents

History of the Osage Nation

Early Osage Life

The Osage people are descendants of ancient cultures that lived in North America for thousands of years. Their traditions and language show they were part of a group of Dhegihan-Siouan speaking people. They originally lived in the Ohio River valley, which includes parts of modern-day Kentucky.

According to their stories, shared with other related tribes, they moved west. This move was likely due to conflicts with the Iroquois tribe or to find more hunting grounds. Some experts believe the Osage began moving west as early as 1200 CE. After crossing the Mississippi River, the Osage sometimes worked with the Illiniwek tribe and sometimes competed with them.

Eventually, the Osage and other Dhegihan-Siouan peoples reached their historical lands. By the 1600s, many Osage had settled near the Osage River in what is now Missouri. They learned to use horses, which they often got by trading or through raids. This desire for horses led them to trade with the French. By 1750, they had become very powerful in the Plains region. They controlled a large area for nearly 150 years.

The Osage were important among the hunting tribes of the Great Plains. From their homes in the woodlands of Missouri and Arkansas, they would go on buffalo hunts twice a year. They also hunted deer, rabbit, and other animals. Near their villages, women grew corn, squash, and other vegetables. They also gathered nuts and wild berries. The Osage blended cultures from both Woodland and Great Plains Native Americans. Their villages were important trading centers on the Great Plains.

Osage Spirituality and Beliefs

Traditional Osage people believe they are deeply connected to the universe. Their ceremonies and social groups reflect what they see around them, created by a supreme life force called Wah'Kon-Tah or Wakonda. They believe everything, from trees and plants to animals and humans, has Wakonda's spirit.

They see two main parts to life: the sky and the earth. Life begins in the sky and comes to earth in physical form. The sky is seen as masculine, and the earth as feminine. They respect animals like hawks, deer, and bears for their courage. They also admire animals that live long, like pelicans. Humans were expected to learn from animals and copy their good qualities for survival.

Wakonda was seen as a mysterious life force in the sun, moon, earth, and stars. It also represented order on Earth, which they believed was often chaotic. People were responsible for their own survival, though they could ask Wakonda for help. They saw warfare as necessary for protecting their community.

Over time, the Osage developed clan and kinship systems that mirrored their view of the cosmos. Clans were often named after parts of their world, like animals, plants, or storms. Each clan had its own duties within the tribe. Some clan names included Red Cedar, Travelers in the Mist, Deer Lungs, and Elk. Children received a ceremonial name to join the community. Without a ceremonial name, an Osage child could not take part in ceremonies. Marriage rules were also based on clans; people had to marry someone from an opposite clan or division.

Osage life was very ritualized. Ceremonies involved sacred bundles and pipes, using tobacco as offerings to Wakonda. These ceremonies were led by Osage medicine people and spiritual leaders. Ceremonies were often elaborate but served basic purposes, like asking Wakonda for the tribe's continued existence and blessings for long life through children.

Ceremonial songs were used to pass down knowledge, as there was no written language. These songs were taught only to those who were sincere and proven worthy. Many songs and ceremonies were created for all parts of life, such as adoption, marriage, war, farming, and honoring the rising sun. During funerals, the faces of deceased Osage were painted to show their tribe and clan.

Contact with Europeans

In 1673, French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet were among the first Europeans to meet the Osage. They traveled south along the Mississippi River. Marquette's map from 1673 showed the Kanza, Osage, and Pawnee tribes living in much of modern-day Kansas.

The Osage called Europeans I'n-Shta-Heh (Heavy Eyebrows) because of their facial hair. The Osage were skilled warriors and allied with the French. They traded with the French and fought against the Illiniwek tribe in the early 1700s. In the 1720s, the Osage and French had more interactions. Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont, built Fort Orleans in Osage territory. This was the first European fort on the Missouri River. Jesuit missionaries also came to French forts to try to convert the Osage.

In 1724, the Osage allied with the French against the Spanish for control of the Mississippi region. In 1725, Bourgmont took Osage and other tribal chiefs to Paris, France. They visited famous places like Versailles and hunted with King Louis XV.

During the French and Indian War, France lost to Great Britain. In 1763, France gave its lands east of the Mississippi River to the British. France made a separate deal with Spain, which took control of lands west of the Mississippi. By the late 1700s, the Osage did a lot of business with French fur traders like René Auguste Chouteau, who was based in St. Louis. The Chouteau brothers built a fort in an Osage village, and in return, they received a six-year monopoly on trade. The Osage were happy to have a trading post nearby, as it gave them access to manufactured goods.

U.S. Government and Land Changes

In 1804, after the United States bought the Louisiana Territory, the U.S. government appointed Jean-Pierre Chouteau as the Indian agent for the Osage. He was a wealthy French fur trader and lived with the Osage for many years. He learned their language and traded with them.

After the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1806, President Jefferson appointed Meriwether Lewis as Indian Agent for the Missouri Territory. There were ongoing conflicts between the Osage and other tribes. The U.S. government wanted to move the Osage out of areas where European-American settlers were arriving.

The U.S. and Osage signed their first treaty on November 10, 1808. In this treaty, the Osage gave up a huge amount of land in what is now Missouri. This treaty created a boundary between the Osage and new settlers. It also said that the U.S. president had to approve all future land sales by the Osage. The treaty also promised that the U.S. would protect the Osage from other tribes. However, the Osage found that the U.S. government often did not keep this promise.

Conflicts with Other Tribes

In the early 1800s, some Cherokee people moved from the southeastern U.S. to the Arkansas River valley. They were pressured by European-American settlers. The Cherokee clashed with the Osage, who controlled this area. The Osage saw the Cherokee as invaders and raided their towns, taking horses and captives. They tried to scare the Cherokee away.

The Cherokee fought back, and in the "Battle of Claremore Mound," 38 Osage warriors were killed, and 104 were captured. After this battle, the United States built Fort Smith in Arkansas to prevent more fighting. The U.S. then forced the Osage to give up more land in a treaty called Lovely's Purchase. In 1833, the Osage also had a conflict with the Kiowa tribe.

Moving to Reservations

Between 1808 and 1825, the Osage gave up their traditional lands in Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma through treaties. In return, they were supposed to receive reservation lands to the west and supplies to help them farm. They were first moved to a reservation in southeastern Kansas.

Missionaries from different Christian churches came to live with the Osage. They tried to convert the Osage and teach their children. However, cultural differences often caused problems. During a smallpox epidemic in 1837–1838, many Native Americans died. All missionaries except the Catholics left the Osage during this time. The Osage believed that the Catholic priests, who stayed and also died, created a special bond between the tribe and the Catholic Church.

In 1843, the Osage asked the U.S. government to send "Black Robes," or Jesuit missionaries, to educate their children. The Jesuits and Sisters of Loretto from Kentucky established schools for Osage children. Many of these missionaries were new recruits from Europe. They taught, built churches, and created the longest-running school system in Kansas.

Civil War and Relocation

White settlers continued to cause problems for the Osage. By 1850, the Osage population had recovered to 5,000 members. The Kansas–Nebraska Act brought many new settlers to Kansas Territory. Both groups who wanted slavery and those who opposed it tried to settle there. Osage lands were soon filled with European-American settlers. In 1855, another smallpox epidemic hit the Osage.

During the American Civil War, the Osage mostly stayed neutral. However, both sides tried to recruit Osage fighters. Some Osage fought for the Confederate States, forming the Osage Battalion. Others were recruited for the Union Army. The Osage faced famine and struggled to survive during the war.

After the Civil War, the U.S. Congress passed the Drum Creek Treaty in 1870. This treaty said that the remaining Osage land in Kansas would be sold. The money from the sale would be used to move the tribe to Indian Territory, which is now Oklahoma. The Osage were able to sell their lands for a better price than first offered.

In 1867, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer used Osage scouts in his campaign against other Native American tribes. He knew the Osage were excellent scouts and warriors.

Moving to Oklahoma

The Osage were one of the few Native American nations to buy their own reservation. This meant they kept more rights to their land and their own government. Most importantly, they kept the mineral rights to their lands. The reservation, about 1.47 million acres, was bought in 1872. It is the same area as present-day Osage County, Oklahoma.

The Osage established four towns: Pawhuska, Hominy, Fairfax, and Gray Horse. Each town was led by one of the main Osage bands. The Osage continued their relationship with the Catholic Church, which set up schools and churches.

It took many years for the Osage to recover from the difficulties of moving. For almost five years in the 1870s, the Osage did not receive all their promised money from the government. Like other Native Americans, they suffered from not getting enough food and supplies. Many people starved. During this time, the Osage population dropped by almost 50 percent.

In 1879, an Osage group went to Washington, D.C. They successfully argued to receive all their payments in cash. This helped them avoid being cheated with poor-quality supplies. They were the first Native American nation to get all their payments in cash. They slowly began to rebuild their tribe but faced problems from white outlaws and thieves.

The Osage wrote their own constitution in 1881, based partly on the U.S. Constitution. By the early 1900s, the U.S. government continued to push for Native Americans to adopt American culture. Congress passed laws like the Curtis Act and Dawes Act. These laws broke up communal lands on other reservations and gave small plots to individual families. The remaining land was sold to non-natives. These laws also tried to dismantle tribal governments.

Oil and Wealth

In 1894, large amounts of oil were discovered under the Osage Nation's land. Henry Foster, who had experience with oil production, asked the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) for permission to explore the Osage Reservation for oil and natural gas. His brother, Edwin B. Foster, took over after Henry died.

The BIA agreed, with the condition that Foster pay the Osage tribe a 10% royalty on all oil sales. Foster found a lot of oil, and the Osage became very wealthy. However, this discovery of "black gold" also brought new challenges.

The Osage had learned how to negotiate with the U.S. government. In 1907, their Principal Chief James Bigheart made a deal. This deal allowed the Osage to keep the communal mineral rights to their reservation lands. These lands later proved to have huge amounts of oil. Tribal members received royalties from oil development. By the 1920s, these royalties had made the Osage dramatically wealthy. In 1923 alone, the Osage earned $30 million in royalties. Since the early 1900s, the Osage are the only tribe in Oklahoma to keep a federally recognized reservation.

In 2000, the Osage sued the federal government. They claimed the government had mismanaged their trust funds and had not paid them correctly. In 2011, the lawsuit was settled for $380 million. The government also promised to make changes to improve how it managed tribal funds. In 2016, the Osage Nation bought Ted Turner's 43,000-acre Bluestem ranch.

Osage Allotment Act

In 1898, the U.S. federal government claimed it no longer recognized the Osage National Council. This council was the government the Osage people had created in 1881. In 1906, as part of the Osage Allotment Act, the U.S. Congress created the Osage Tribal Council. This was done to prepare for Oklahoma to become a state in 1907.

Because the Osage owned their land, they were in a stronger position than other tribes. They refused to give up their lands and delayed Oklahoma's statehood until they signed an allotment act. They were forced to accept allotment, but they kept their "surplus" land after individual households received their plots. This surplus land was then divided among all individual members. Each of the 2,228 registered Osage members in 1906 received 657 acres. This was nearly four times the amount of land given to most Native American households elsewhere.

The tribe kept the communal mineral rights to everything under the surface. As oil was developed, tribal members received royalties based on their "headrights." These headrights were tied to the amount of land they held. By the early 1900s, the Osage were the only tribe in Oklahoma to keep a federally recognized reservation.

Although the Osage were encouraged to become farmers, their land was not good for farming. They survived by farming for their own food and raising livestock. They also leased land to ranchers for grazing, earning income from fees. Besides breaking up communal land, the act replaced the tribal government with the Osage National Council. This council was elected to manage the tribe's affairs.

Initially, every Osage male had equal voting rights for the council. In future generations, the rights to these lands and mineral royalties were divided among legal heirs. Under the Allotment Act, only those who held headrights could vote or run for office. This system created inequalities among voters.

In 2004, Congress passed a law to restore sovereignty to the Osage Nation. This allowed them to make their own decisions about their government and who could be a member. In March 2010, a U.S. court ruled that the 1906 Allotment Act had ended the Osage reservation established in 1872. This ruling affected the legal status of some Osage casinos, as casinos can only operate on federal trust land.

The Osage Nation's largest business, Osage Casinos, opened new casinos and hotels in Skiatook and Ponca City in December 2013.

Natural Resources and Headrights

Before voting on allotment, the Osage demanded that the government remove people who were not legally Osage from their tribal rolls. The Indian agent had added names of people not approved by the tribe. The Osage submitted a list of over 400 people to be investigated. Because the government removed few of these people, the Osage had to share their land and oil rights with people who did not truly belong.

The Osage had successfully negotiated to keep communal control of their mineral rights. The act stated that all persons on tribal rolls before January 1, 1906, or born before July 1907 (called allottees), would receive a share of the reservation's underground natural resources. This was regardless of their "blood quantum" (how much Native American ancestry they had). This "Osage headright" could be inherited by legal heirs. This communal claim to mineral resources was supposed to end in 1926. After that, individual landowners would control the mineral rights to their plots. This deadline increased the pressure for non-Native Americans to gain control of Osage lands.

Although the Osage Allotment Act protected the tribe's mineral rights for two decades, any adult "of a sound mind" could sell surface land. Between 1907 and 1923, Osage individuals sold or leased thousands of acres to non-Native Americans. At the time, many Osage did not fully understand the value of these contracts. They were often taken advantage of by dishonest business people and con artists. Non-Native Americans also tried to gain Osage wealth by marrying into families who held headrights.

Challenges with Wealth

In 1921, the U.S. Congress passed a law. It required any Osage person with half or more Native American ancestry to have a guardian appointed for them until they proved they were "competent." Minors with less than half Osage ancestry also needed guardians, even if their parents were alive. Local courts appointed these guardians, usually white attorneys and businessmen. By law, guardians provided a $4,000 annual allowance to the Osage people they managed. Initially, the government did not require much record-keeping of how the rest of the money was used.

Royalties for people holding Osage headrights were much higher, ranging from $11,000 to $12,000 per year between 1922 and 1925. Guardians were allowed to collect $200–$1,000 per year, and the attorney involved could collect $200 per year. Some attorneys served as guardians for four Osage people at once, allowing them to collect $4,800 per year.

The guardianship program created opportunities for corruption. Many Osage people were unfairly deprived of their land, headrights, or royalties. There was also a difficult period in the early 1920s where many Osage faced unfair treatment and suspicious deaths. The coroner's office sometimes falsified death certificates. The Osage Allotment Act did not give Native Americans the right to autopsies, so many deaths were not properly investigated.

The Osage author John Joseph Mathews wrote about the challenges the oil boom brought to the Osage Nation in his novel Sundown (1934). The book Killers of the Flower Moon (2017) by David Grann also explores this period. A major movie based on the book was released in 2023.

Changes to Laws and Management

As a result of the challenges and to protect Osage oil wealth, Congress passed a law in 1925. This law limited the inheritance of Osage headrights only to heirs with half or more Osage ancestry. They also extended the tribe's control of mineral rights for another 20 years. Later laws gave the tribe continuing communal control indefinitely. Today, headrights are mostly passed down among descendants of the original Osage holders. However, the Bureau of Indian Affairs estimates that 25% of headrights are owned by non-Osage people, including other Native Americans, non-Indians, churches, and community groups. The BIA continues to pay royalties quarterly.

Starting in 1999, the Osage Nation sued the United States government. They claimed the government had mismanaged their trust funds and mineral estate. In February 2011, a court awarded $330.7 million in damages for some of the mismanagement claims from 1972 to 2000. On October 14, 2011, the United States settled the entire lawsuit for a total of $380 million. The settlement also included promises from the U.S. to work with the Osage to create new ways to protect tribal trust funds and resources.

Osage Nation Today

The Osage Nation's population in 2017 was estimated at 47,350 people. Their reservation covers about 1.47 million acres.

Government of the Osage Nation

In 1994, the Osage voted for a new constitution. It stated that original allottees and their direct descendants, regardless of blood quantum, were citizens of the Osage Nation. However, this constitution was overturned by court decisions. The Osage then asked Congress for support to create their own government and membership rules. In 2004, President George W. Bush signed a law that confirmed the Osage Tribe's right to decide its own membership and government.

From 2004 to 2006, the Osage Government Reform Commission worked to develop a new government. On March 11, 2006, the Osage people voted to approve a new constitution. A major part of this new constitution was to give every citizen of the nation "one person, one vote." Before this, people voted based on their headrights, which was like being a shareholder. The Osage Nation adopted this new government structure by a two-thirds majority vote. They also approved the definition of who is a member of the nation.

Today, the Osage Nation has 13,307 enrolled tribal members, with 6,747 living in Oklahoma. Since 2006, membership is based on being a direct descendant of someone listed on the Osage rolls from the 1906 Allotment Act. A minimum blood quantum is not required. However, the Bureau of Indian Affairs requires 25% or more blood quantum for federal education scholarships. So, the Osage Nation works to support higher education for its students who don't meet that requirement.

The tribal government is based in Pawhuska, Oklahoma. It has authority in Osage County, Oklahoma. The Osage Nation's government has three separate branches: executive, judicial, and legislative. These branches are similar to the United States government. The tribe publishes a monthly newspaper called Osage News. The Osage Nation also has an official website and uses various communication methods.

Judicial Branch

The judicial branch has courts that interpret the laws of the Osage Nation. It handles civil and criminal cases, resolves disagreements, and reviews laws. The highest court is the Supreme Court. The current Chief Justice is Meredith Drent. There is also a lower Trial Court and other courts as allowed by the tribal constitution.

Executive Branch

The executive branch is led by a principal chief and an assistant principal chief. The current principal chief is Geoffrey Standing Bear, and Raymond Red Corn is the assistant principal chief. Administrative offices also fall under this branch.

Osage Nation Museum

The Osage Nation Museum is located in Pawhuska, Oklahoma. It shows and explains Osage history, art, and culture. The exhibits change often and tell the story of the Osage people through time, celebrating their culture today. The museum has a large collection of photographs, historical items, and traditional and modern art. Founded in 1938, it is the oldest museum owned by a tribe in the United States. Historian Louis F. Burns donated many of his personal items and documents to the museum. In 2021, ancient Osage art was found in a Missouri cave. The art was sold at auction, but the Osage leadership believes it belongs to the nation.

Legislative Branch

The legislative branch is a Congress that creates and maintains Osage laws. Its job is also to make sure the different parts of the Osage government balance each other. It oversees government activities, supports tribal income, and protects the nation's environment. This Congress has twelve members who are elected by Osage citizens for four-year terms. They hold two regular sessions each year and are based in Pawhuska.

Mineral Council

The Osage Tribal Council was created by the Osage Allotment Act of 1906. It included a principal chief, an assistant principal chief, and eight council members. The mineral estate includes more than just natural gas and petroleum. While these two resources have made the most money, the Osage have also earned income from leases for mining lead, zinc, limestone, and coal. Water may also be considered a valuable resource controlled by the Mineral Council.

The first elections for this council were held in 1908. Officers were elected for two-year terms, which made it hard to achieve long-term goals. If the principal chief's office became empty, the remaining council members would elect a replacement. Later, the tribe increased the terms of office for council members to four years.

In 1994, the tribe voted for a new constitution. One of its rules was to separate the Mineral Council, or Mineral Estate, from the regular tribal government. According to the constitution, only Osage members who hold Osage headrights can vote for the members of the Mineral Council. This is similar to how shareholders vote in a company.

Education

In July 2019, the tribe officially recognized Bacone College in Muskogee, Oklahoma, as its tribal college.

School districts in the Osage Nation include Hominy School District, Pawhuska School District, and Woodland School District (of Fairfax). There is also a private immersion school called Daposka Ahnkodapi Elementary School. The Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) does not have any facilities directly operated or connected to the nation.

Economy

The Osage Nation issues its own tribal vehicle tags and runs its own housing authority. The tribe owns a truck stop, a gas station, and ten smoke shops.

In the 21st century, the Osage Nation opened its first gaming casino. As of December 2013, they have seven casinos. These casinos are located in Tulsa, Sand Springs, Bartlesville, Skiatook, Ponca City, Hominy, and Pawhuska. In 2010, the tribe's yearly economic impact was estimated to be $222 million. Osage Million Dollar Elm, the company that manages the casinos, encourages employees to get more education. They pay for classes related to their business, as well as for bachelor's and master's business degrees.

Notable Osage People

- Fred Lookout (1865–1949), a principal chief.

- Monte Blue (1887–1963), an American actor from the silent and sound film eras.

- Louis F. Burns (1920–2012), a historian and author, known for his knowledge of Osage history and customs.

- Cody Deal (b. 1986), a television and film actor.

- Jerry C. Elliott (b. 1943), one of the first Native Americans in NASA. He received the Presidential Medal of Freedom for helping to save the astronauts on Apollo 13.

- Guy Erwin (b. 1958), the first openly gay bishop in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

- Shonke Mon-thi^, a diplomat to the United States government in the early 1900s.

- Yatika Starr Fields (b. 1980), a painter, muralist, and street artist.

- David Holt (politician) (b. 1979), the Mayor of Oklahoma City. He was the first Osage elected to state office since 2006.

- Kihegashugah or Little Chief, an Osage leader who traveled to France in the 1820s.

- John Joseph Mathews (c. 1894–1979), an author and historian of the Osage Nation.

- Carter Revard (1931-2022), a poet, author, and Rhodes Scholar.

- Chance Rencountre (born 1986), a mixed martial artist.

- Lucille Robedeaux (1915–2005), a tribal elder and the last native speaker of the Osage language.

- Sacred Sun, a 19th-century Osage woman who visited France.

- Larry Sellers, an actor, stuntman, and language mentor.

- Maria Tallchief, a famous classical ballerina with the New York City Ballet.

- Marjorie Tallchief, also a professional ballerina. Both sisters were prima ballerinas who performed worldwide.

- Clarence L. Tinker (1887–1942), a U.S. Army aviation officer who died during World War II. Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma City is named in his honor.

- Chief White Hair, the name of several Osage leaders in the 1700s and 1800s. The town of Pawhuska, Oklahoma, is named after him.

See also

In Spanish: Osage para niños

In Spanish: Osage para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |