Joseph LaFlesche facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

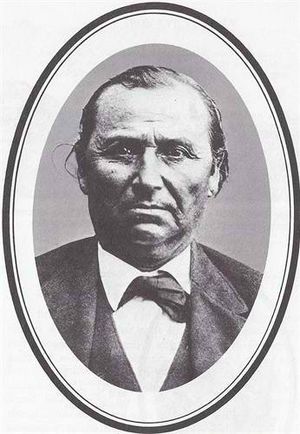

Joseph LaFlesche

|

|

|---|---|

| E-sta-mah-za | |

The last recognized head chief of the Omaha tribe of Native Americans

|

|

| Born | 1822 |

| Died | 1888 |

| Known for | Last recognized Head Chief of the Omaha Tribe |

| Children | |

Joseph LaFlesche, also known as E-sta-mah-za or Iron Eye (1822–1888), was a very important leader of the Omaha tribe. He was the last head chief chosen in the traditional way. The previous chief, Big Elk, adopted LaFlesche and chose him to be his successor in 1843. Joseph LaFlesche had both Ponca and French Canadian family roots. He became chief in 1853 after Big Elk passed away. He was known for being the only Omaha chief with European family background at that time.

In 1854, LaFlesche was one of seven Omaha chiefs who traveled to Washington, D.C. There, they signed a treaty with the United States. This agreement meant the Omaha tribe gave up most of their land. Around 1856, he led his people to a new home on the Omaha reservation in what is now northeastern Nebraska. LaFlesche was the main chief until 1888. He guided the Omaha people through many big changes as they moved to the reservation.

Early Life and Learning

Joseph LaFlesche, also called E-sta-mah-za (Iron Eye), was the son of Joseph LaFlesche, a French-Canadian fur trader. His mother, Waoowinchtcha, was a Ponca woman.

From the age of 10, young Joseph traveled with his father on trading trips. His father worked for the American Fur Company. They traded with many tribes like the Ponca, Omaha, Iowa, Otoe, and Pawnee. These tribes lived near the Platte and Nebraska rivers. Joseph and his father learned the Omaha-Ponca language from his mother and the Omaha people.

Becoming a Leader

Joseph La Flesche started working for the American Fur Company when he was about 16. He worked there until 1848. By then, he had settled with his family and the Omaha people at the Bellevue Agency. Chief Big Elk adopted him into the Omaha tribe. In 1843, Big Elk chose LaFlesche to be the next chief. Joseph then began to learn all about the tribe's ways and customs. He joined the tribal council around 1849.

Family Life

LaFlesche married Mary Gale (born around 1825-1826, died 1909). Mary was the daughter of Dr. John Gale, an army surgeon, and his Iowa wife Ni-co-ma. When Dr. Gale left the fort in 1827, he left Mary and her mother with her family.

Joseph and Mary LaFlesche had five children: Louis, Susette, Rosalie, Marguerite, and Susan. Joseph and Mary believed that education was important for Native Americans. They also thought that adopting some European ways, like farming and Christianity, would help their people. They encouraged their children to get good educations and work to help their tribe. Sometimes, LaFlesche sent his children to schools in the East.

As a chief, Joseph LaFlesche could have more than one wife. He also married Ta-in-ne, an Omaha woman known as Elizabeth Erasmus. They had a son named Francis, born in 1857, and other children.

His children with Mary became important figures. Susette LaFlesche Tibbles was an activist. Rosalie La Flesche Farley managed the Omaha tribe's money. Marguerite La Flesche Diddock became a teacher on the Yankton Sioux Reservation. Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte was the first Native American woman in the United States to become a doctor. Susan worked with the Omaha and built the first privately funded hospital on an Indian reservation for them.

Their half-brother Francis La Flesche, son of Ta-in-ne, became an ethnologist for the Smithsonian Institution. He lived in Washington, D.C., but returned to the West to study the Omaha and the Osage tribes. Even though the siblings had different ideas about land ownership and adopting new ways, they all worked to improve life for Native Americans, especially the Omaha in Nebraska.

Chief of the Omaha

The Omaha tribe had a system where leadership passed down through the father's side of the family. In 1843, Big Elk chose LaFlesche to be his successor as a hereditary chief of the Weszhinste. This was one of the ten main family groups (called gentes) of the Omaha.

The Omaha were divided into two main parts, representing Earth and Sky. Each part had five family groups, and each group had hereditary chiefs. The two head chiefs worked together to keep balance in the tribe. If a child had a white father and an Omaha mother, they were not automatically part of the tribe. They were considered white. To become a tribe member, they had to be formally adopted. Without adoption, they could not become a hereditary chief.

When Big Elk adopted LaFlesche (Iron Eye) and chose him as his successor, LaFlesche studied the tribal ways very carefully. He wanted to be ready to be chief. Big Elk was chief until he died in 1853, and then LaFlesche became chief. It was said that he was the only Omaha chief who had any white family background.

In January 1854, after talks with 60 Omaha men, the tribe agreed to give up some land to the U.S. government. They chose seven chiefs to go to Washington, D.C., to finalize the land sale. These chiefs included LaFlesche, Two Grizzly Bears, Standing Hawk, Little Chief, Village Maker, Noise, and Yellow Smoke. Logan Fontenelle, a man with both white and Native American heritage, went with them as an interpreter. The treaty was signed in March 1854.

The U.S. government made many changes to the treaty. They greatly reduced the money paid to the Omaha for their land. Also, instead of all cash, the payments would be a mix of cash and goods. The Omaha tribe would receive payments each year until 1895. The U.S. President would decide how much of the payment would be money and how much would be goods.

As chief, LaFlesche guided the tribe through a time of big changes. They moved to the reservation in what is now northeast Nebraska in the Blackbird Hills. About 800 Omaha people moved there. At first, they built their traditional sod lodges in a circle. By 1881, the tribe had grown to about 1100 people. Many had built houses like those of European settlers. LaFlesche worked to help the Omaha gain the rights of U.S. citizens. At that time, the U.S. government often required Native Americans to give up their shared land and tribal government to become citizens.

LaFlesche supported the idea of individual land ownership. He believed that tribe members would benefit from owning their own land instead of sharing it as a tribe. Many in the tribe had different ideas. In the end, breaking up the shared lands caused problems for the tribe's way of life and land use. LaFlesche encouraged his people to get an education in both Omaha and American ways. He supported the mission schools. He also worked to ensure the well-being of the community by setting rules for healthy living on the reservation. He and Henry Fontenelle were chosen to be official traders for the Omaha.

LaFlesche was chief during a time when many Omaha people found it hard to accept the changes happening in their lives. For a while, many men lived on their yearly payments and by hunting. The women continued to grow corn together. The Omaha stayed in their villages instead of farming individual plots of land.

By 1880, the Omaha were growing a lot of wheat, even enough to sell some. However, the next year was not good for crops. The government's plan for dividing land often meant that future generations would inherit very small pieces of land. These small plots were too tiny to farm well or use for other things. Also, when government payments and supplies were late or in bad condition, the Omaha faced very difficult times on their reservation.

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |