Susan La Flesche Picotte facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Susan La Flesche Picotte

|

|

|---|---|

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte

|

|

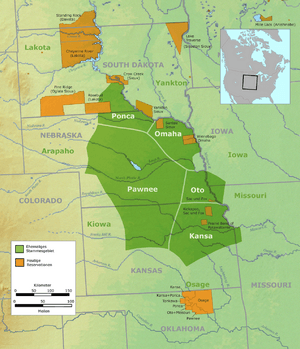

| Born | June 17, 1865 Omaha Reservation, United States

|

| Died | September 18, 1915 (aged 50) Walthill, Nebraska, United States

|

| Nationality | Omaha, Ponca, Iowa, French, and Anglo-American descent |

| Alma mater | Hampton Institute Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Known for | First Indigenous woman to become a physician in the United States |

| Parent(s) | Joseph LaFlesche and Mary Gale |

| Relatives | Susette La Flesche (sister) Francis La Flesche (half-brother) |

Susan La Flesche Picotte (June 17, 1865 – September 18, 1915) was a Native American doctor and reformer. She was the first Indigenous woman to earn a medical degree in the United States. She worked hard for better public health and for land to be given to members of the Omaha tribe.

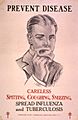

Picotte was also a social reformer. She worked to discourage drinking on the reservation where she was a doctor. She also campaigned to prevent and treat tuberculosis, a serious illness with no cure at the time. She helped Omaha people understand government rules about their land and money.

Contents

Early Life

Susan La Flesche was born in June 1865. Her family lived on the Omaha Reservation in eastern Nebraska. Her parents were from the Omaha tribe. They also had European and Indigenous family members.

Susan’s father, Joseph LaFlesche, was also called Iron Eye. He was part Ponca and part French Canadian. He became the main leader of the Omaha tribe around 1855. Iron Eye wanted his people to adopt some ways of the white world. He supported giving land to individual families.

Susan’s mother, Mary Gale, was the daughter of a white army doctor and a woman of Omaha, Otoe, and Iowa heritage. Mary Gale spoke only the Omaha language.

Susan was the youngest of four girls. Her older half-brother, Francis La Flesche, became famous for studying Omaha and Osage cultures. Susan learned her tribe's traditions. However, her parents did not give her an Omaha name. They also stopped her from getting traditional tattoos. She spoke Omaha with her parents. Her father and oldest sister encouraged her to speak English too.

As a child, Susan saw a sick Indigenous woman die because a white doctor refused to help her. This sad event inspired Susan to become a doctor. She wanted to care for her own people on the Omaha Reservation.

Education

School Days

Susan La Flesche started school at a mission on the reservation. This school was a boarding school. Native children were taught European American ways there. The goal was to help them fit into white society.

After some years, LaFlesche left the reservation. She studied in Elizabeth, New Jersey, for two and a half years. In 1882, she returned to the reservation and taught at a school there. She later went to the Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia. This school was for African American students. It also welcomed Native American students.

LaFlesche graduated from Hampton on May 20, 1886. She was the second-highest-ranking student in her class. She also won a prize for having the best test scores. Most girls from Hampton Institute were encouraged to become teachers or homemakers. But LaFlesche decided to apply to medical school in 1886.

Becoming a Doctor

It was rare for women in the United States to go to medical school in the late 1800s. Only a few medical schools accepted women.

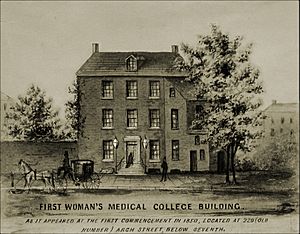

LaFlesche was accepted at the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP). This school was one of the first to train women as doctors. Medical school was expensive. LaFlesche could not afford it on her own. She asked her family friend, Alice Cunningham Fletcher, for help. Alice Fletcher knew many people in women's groups.

Fletcher encouraged LaFlesche to ask the Connecticut Indian Association for help. This group wanted to help Native Americans adopt American customs. They sponsored LaFlesche's medical school costs. They also paid for her housing, books, and other supplies. She was the first person to get help for professional education in the U.S. The group asked her to stay single during medical school and for a few years after. This was so she could focus on her work.

At WMCP, LaFlesche studied many subjects. These included chemistry, anatomy, and physiology. She also did hands-on work in hospitals. She started to dress like her white classmates. She wore her hair in a bun.

After her second year, LaFlesche went home to help her family. Many of them were sick with measles. She sent letters with medical advice during the rest of her schooling.

She graduated at the top of her class on March 14, 1889. She finished her studies in three years.

After graduating, she went on a speaking tour. She told white audiences that Native Americans could benefit from white civilization. The Connecticut Indian Association also made her a medical missionary to the Omaha. They bought her medical tools and books.

Medical Practice

LaFlesche returned to the Omaha reservation in 1889. She became the doctor at the government boarding school. Her job was to teach students about hygiene and keep them healthy.

The school was close to many people on the reservation. So, LaFlesche also cared for the wider community. She often worked 20-hour days. She was responsible for over 1,200 people.

From her small office, she helped people with their health. She also helped with everyday tasks. She wrote letters and helped translate official papers.

People in the community trusted her. She visited homes and cared for patients with tuberculosis, influenza, and other illnesses. Her first office was also a meeting place for the community.

She worked for several years, traveling the reservation to see patients. She earned a salary from the government. She also received money from the Women's National Indian Association.

In 1893, she had to take time off. She needed to care for her sick mother and her own health. She resigned to care for her dying mother.

In June 1894, LaFlesche married Henry Picotte. They had two sons, Caryl and Pierre. Picotte continued to practice medicine after her children were born. This was unusual for women at that time. Her husband's support made it possible. She treated both Omaha and white patients. Sometimes, she even took her children with her on house calls.

Public Health Work

Picotte worked on many public health issues. These included school hygiene and food safety. She also fought against the spread of tuberculosis (TB). She was on the health board of Walthill. She also helped start the Thurston County Medical Society in 1907.

Picotte believed that education was key to fighting disease. She led efforts to teach people about public health. She also pushed for a hospital to be built on the reservation. It was finished in 1913 and later named after her. This was the first privately funded hospital on a reservation.

Her most important fight was against tuberculosis. This disease killed many Omaha people, including her husband Henry in 1905. She asked the government for help, but they said they lacked money. Since there was no cure, Picotte taught people about cleanliness and fresh air. She also told them to get rid of houseflies, which were thought to spread TB.

Helping Her Community

Picotte's husband Henry died in 1905. He left land to her and their two sons. But the land was held by the government. To get money from its sale, they had to prove they could manage it. This process was long and difficult. Picotte had to send many letters to the government office. She finally received her share of the money in 1907. Getting her sons' money was even harder.

Picotte wrote many letters to the head of the Indian Office. She argued that she was the best person to manage her sons' money. Her letters worked. The government told the local agent to let her sell the land.

Picotte invested this money in rental properties. This income helped her support herself and her sons. She continued to fight government rules for her children's inheritance. She won again in 1908.

Picotte also helped other Omaha people with their land issues. As a doctor, she had earned the trust of her community. She became a local leader. She helped Omaha people who wanted to sell their land. She also tried to stop white people from unfairly taking advantage of Native Americans.

In 1909, Picotte wrote to the Indian Office. She said some of her people needed government help to protect themselves from unfair land deals. In 1910, she went to Washington, D.C. She told officials that the government had not helped Native Americans learn business skills. She argued that this made some Omaha people unable to protect themselves.

She also fought against combining the Omaha and Winnebago government offices. She said this would create more unnecessary rules. She believed it showed the government treated Native Americans like children. Picotte continued to work for her community until she died.

Later Life and Legacy

Picotte suffered from health problems for most of her life. She had trouble breathing in medical school. She also had chronic pain. Over time, she became deaf.

Her health got worse as she got older. When the new hospital was built in Walthill in 1913, she was too weak to run it alone. She died of bone cancer on September 18, 1915. She is buried in Bancroft Cemetery in Bancroft, Nebraska.

Picotte's sons lived full lives. Caryl Picotte served in the United States Army in World War II. Pierre Picotte lived in Walthill, Nebraska, and raised a family.

During her career, Picotte cared for over 1,300 patients. She covered a large area of 450 square miles.

Tributes

The reservation hospital in Walthill, Nebraska, is named after Picotte. It is now a community center. It was named a National Historic Landmark in 1993.

An elementary school in western Omaha, Nebraska, is named after Picotte.

On June 17, 2017, Google honored Picotte with a Google Doodle. This was on her 152nd birthday.

In 2018, a statue of Picotte was placed in Sioux City. In 2019, another statue was dedicated at Hampton University.

On October 11, 2021, a bronze sculpture of Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte was unveiled in Lincoln, Nebraska. Her descendants were there for the event.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Suzanne La Flesche Picotte para niños

In Spanish: Suzanne La Flesche Picotte para niños

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |