Logan Fontenelle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

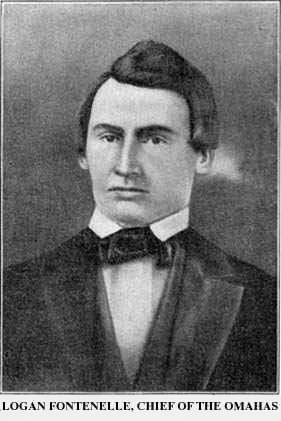

Logan Fontenelle

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Chief | |

| In office 1853–1855 |

|

| Preceded by | Big Elk |

| Succeeded by | Iron Eye |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 6, 1825 Fort Atkinson |

| Died | July 16, 1855 (aged 30) Boone County, Nebraska |

| Residence | Nebraska Territory |

| Profession | Chief, interpreter |

Logan Fontenelle (born May 6, 1825 – died July 16, 1855) was also known as Shon-ga-ska (White Horse). He was a trader with both Omaha and French family roots. For many years, he worked as an interpreter for the U.S. Indian agent at the Bellevue Agency in Nebraska.

Logan Fontenelle played a very important role in 1853–1854. During this time, the United States was talking with Omaha leaders about giving up their land. This was before the Omaha people moved to a special area called an Indian reservation. Logan's mother was the daughter of Big Elk, a main chief. His father was a respected French-American fur trader.

Some European Americans thought Fontenelle was a chief. However, the Omaha people did not see him as part of their tribe because his father was white. The Omaha had a patrilineal system. This means a child's family group came from their father. Logan could only become a chief if an Omaha man formally adopted him. The Omaha people called him a "white man" because of his father.

Fontenelle lived on the reservation. He died young at age 30. He was killed along with five other Omaha people. This happened during a tribal summer buffalo hunt. An enemy group of Sioux warriors attacked them.

Fontenelle helped the Omaha people talk with the United States. This was during 1853–1854 when they were giving up land. First, 60 Omaha leaders and the U.S. Indian agent Gatewood met in Nebraska. They reached an agreement in January 1854. Later that year, Fontenelle went with seven Omaha chiefs to Washington, D.C., for more talks.

Fontenelle was one of the people who signed the treaty. He might have signed because he was the only Omaha speaker there who could read English. The Omaha chiefs had to accept changes to the treaty during that trip. They agreed to give up about 4 million acres (16,000 km2) of their land to the United States. They hoped this would protect them from the Sioux, but they were disappointed. Within a few years, the Omaha moved to a reservation in northeast Nebraska. This area is mostly Thurston County today.

Biography

Early years

Logan Fontenelle was born at Fort Atkinson, Nebraska Territory. His birthday was May 6, 1825. He was the oldest of four sons. His mother was Me-um-bane, a daughter of the main Omaha chief Big Elk (1770–1846/1853). His father was Lucien Fontenelle, a French-American fur trader from New Orleans.

Logan's brothers were Albert (1827–1859), Tecumseh (Felix) (1829–1858), and Henry (born 1831). His sister was Susan (1833–1897). Logan's father sent his sons to St. Louis, Missouri for schooling like European Americans. His daughter Susan learned at home and in local mission schools. She later married Louis Neals.

In 1828, Lucien Fontenelle bought a trading post. It became known as Fontenelle's Post. He worked for the American Fur Company on the Missouri River. This area later became Bellevue, Sarpy County, Nebraska. By 1832, the fur trade was slowing down. Fontenelle sold the post to the U.S. government.

The government used the buildings as the main office for the regional Indian agency. It was called the Upper Missouri Indian Agency or Bellevue Agency. This agency managed relationships with the Omaha and other local tribes. In the years that followed, the Indian agent led talks with tribes. They wanted tribes to give up land to the United States for American settlers.

Return to Nebraska

Logan Fontenelle was 15 when his father died in 1840. He returned from St. Louis to Nebraska. There, he started working as an interpreter for the U.S. Indian Agent at the Bellevue Agency. He also worked as a trader.

In August 1846, he helped Big Elk as an interpreter. Big Elk signed a treaty with Brigham Young. This treaty allowed Mormon pioneers to build a settlement on Omaha land. The United States wanted to be part of all treaties about Native American land. So, this treaty was not legal. The Omaha leaders did not have guns. They hoped the Mormons would protect them from the Sioux, who were raiding them. The Omaha probably thought it was a bad deal later. The Mormons used many local resources and did not protect them much.

In the spring of 1843, Logan married Gixpeaha ("New Moon"), an Omaha woman. He built a house for them near his father's home. They had three daughters: Emily (born in 1845), Marie (born December 21, 1848), and Susan (born February 8, 1850). In 1846, Father Christian Hoecken baptized Gixpeaha and baby Emily. He also made their marriage official. In December 1850, Father Hoecken baptized Marie and Susan.

Fontenelle became friends with Joseph La Flesche (1822–1888). Joseph was a Métis (someone with mixed Native American and European heritage) fur trader. He had been adopted by the main Omaha chief Big Elk. Around 1848, the Omaha moved to the Bellevue Agency. Big Elk had chosen LaFlesche to be his successor. So, LaFlesche brought his family to live with the tribe.

Around this time, LaFlesche and Fontenelle started a ferry service. It crossed the Platte River near where Columbus, Nebraska is today. This helped the growing number of travelers. Later, they started another ferry across the Elkhorn River near Fremont, Nebraska. After making money, they sold the ferries to English immigrants.

In the summer of 1854, some people from Quincy, Illinois, wanted to start a new town. They asked Fontenelle to choose a good spot. He took them to a place overlooking the Elkhorn River. It was about forty miles northwest of Bellevue. The men asked Fontenelle how much he wanted for twenty square miles of land for their town. He said one hundred dollars. But he lowered the price when they decided to name the town and a nearby creek after him. The town was officially started on March 14, 1855. The creek was named Logan.

Treaty negotiations

The U.S. Indian Agent James M. Gatewood was being pressured by the government. They wanted him to get the Omaha to give up their land. The Omaha, in turn, wanted protection from the U.S. government against the Sioux. The Sioux often raided them. The Omaha also wanted ways to support themselves in the future.

In January 1854, 60 Omaha leaders met to talk about the treaty. They were careful about letting even their main chiefs handle such an important matter alone. Together, the large group of men negotiated a treaty with Agent Gatewood. Fontenelle worked as the interpreter. The treaty included payments for tribal debts to traders like Fontenelle, Louis Saunsouci, and Peter Sarpy.

The Omaha finally chose seven chiefs to go to Washington, D.C. They were Joseph LaFlesche (Iron Eye), Two Grizzly Bears, Standing Hawk, Little Chief, Village Maker, Noise, and Yellow Smoke. Fontenelle and Saunsouci went with the chiefs as interpreters. Joseph LaFlesche had been chosen by Big Elk to be his successor. In 1853, he became chief of the Wezhinshte group. Both he and Fontenelle signed the Treaty of 1854. Five other chiefs also signed it. Through this treaty, the tribe sold almost all its land to the government. Fontenelle may have signed for one of the other chiefs. This is because he was the only one of the Omaha speakers who could read English.

The reservation was set up on land in the Blackbird Hills. This area is mostly Thurston County today. The Bureau of Indian Affairs changed the treaty terms. They were less favorable than what Gatewood and the 60 Omaha had agreed to in Nebraska. For example, the Omaha were to get much less money for their land. Also, the President could choose to give the yearly payments in cash or goods. The Omaha wanted all cash. Payments were to be made until 1895.

About 800 Omaha people moved to the reservation. Their numbers grew to 1100 by 1881. Under the treaty, the Omaha tribe received money each year. They got $40,000 per year for three years starting January 1, 1855. Then $30,000 per year for the next ten years. Then $20,000 per year for the next fifteen years. And finally, $10,000 per year for the next twelve years, until 1895. The President of the United States decided how much money and goods they would receive each year. This was based on advice from the U.S. Indian Office.

Death

In 1855, a group of Brulé Sioux killed Fontenelle and five of his group. They were part of the Omaha summer buffalo hunt. This happened along Beaver Creek in what is now the Olson Nature Preserve in Boone County, Nebraska. John Bigelk, who was Big Elk's nephew, described the Sioux attack. He said, "They killed the white man, the interpreter, who was with us."

Historian Melvin Randolph Gilmore explained why Big Elk called Fontenelle "a white man." It was because Logan had a white father. This was a common way for full-blood Native Americans to describe people of mixed race. This is similar to how a person of mixed Black and white heritage might be called "Black" by white people. The Omaha tribe followed a patrilineal system. This meant a child's social identity came from their father.

Iron Eyes (Joseph LaFlesche) told how Fontenelle died. He said, "Logan could have run away like I did. But he lay down in the grass and tried to fight the Sioux alone. His first shot missed, but with the second, he killed a Sioux. The Sioux thought there were two men there, and those in front stopped. Another group of about a dozen attacked him from behind. Logan had reloaded his gun. As they came up, he turned and killed two of them. The group in front rushed in before he could reload and killed him."

After the battle with the Sioux ended, the survivors found Fontenelle's body. Louis Saunsouci carried the body back to camp. It was wrapped in buffalo robes. It was placed on a travois (a type of sled) pulled by Fontenelle's horse. They had gotten the horse back from the Sioux during the fight. They sent messengers ahead and traveled back to Bellevue.

A person who saw the funeral said that a procession moved slowly. Louis San-so-see (Saunsouci) led it, driving a wagon. Logan Fontenelle's body was in the wagon, wrapped in blankets and buffalo robes. On each side, Indian chiefs and warriors rode ponies. The women and relatives of the dead expressed their sadness with mournful cries. His body was taken to his house. A coffin was made, but it was too small without unfolding the blankets. It was a hard task because he had been dead for a while. After he was put in the coffin, his wives cried sadly. They cut their ankles until blood flowed. An old Indian woman stood between the house and the grave. She raised her arms to the sky and cursed the killers.

Col. Sarpy, Stephen Decatur, Mrs. Sloan, and others stood by the grave. When his body was lowered, Decatur read the funeral service of the Episcopal church. Mrs. Sloan interrupted him. She stood by his side and loudly told him that "a man of his character ought to be ashamed of himself to make a mockery of the Christian religion." Decatur read the service because no clergy were there. He finished it. After the white mourners, led by Col. Sarpy, paid their respects, the Native Americans walked around the grave. They showed their sorrow. Another account says that after the white mourners left, the Native Americans had their own speeches and sang funeral songs into the night.

After Logan died, his wife Gixpeaha went to live on the Omaha reservation. She lived to be old. Their daughters Marie and Susan married Omaha men and had families. His oldest daughter Emily was not married when she died in 1869.

Chiefdom dispute

Some historians believe that Fontenelle became a chief of the Omaha in 1853. This was after Big Elk died. However, this idea is not supported by facts. Big Elk had chosen Joseph LaFlesche to be his successor. Also, people at the time said that Fontenelle was respected. But only the white people thought he was a chief. They were the only ones who honored him after he died.

It seems there was confusion because he went with the chiefs to Washington, D.C., as an interpreter. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) also used Saunsouci as an interpreter. For some reason, officials put Fontenelle's name as one of the seven chiefs on the treaty. He signed it. But the name of chief Two Grizzly Bears was not included, and he did not sign. Fontenelle was the only Omaha speaker in the group who could read English.

Historian Judith Boughter suggests that Agent Gatewood might have told BIA officials that Fontenelle was a chief. Or perhaps the Omaha did this to make him seem more important. He might also have been seen as an honorable chief because of his kind actions and gifts to the tribe.

An 1889 description of Joseph LaFlesche said he was the only Omaha chief with any European blood. As mentioned, Big Elk adopted him as a son. This is how he fully became part of the tribe. A. T. Andreas called Fontenelle the "last great chief" of the Omaha in his 1882 history of Nebraska. But the idea that he was a chief is not supported by what we know about tribal structure. It is also not supported by what people at the time thought. This was shown in 1919 by Melvin R. Gilmore and by Judith Boughter. It seems that only white people thought Fontenelle was a chief during his life and after his death.

As Gilmore noted, the Omaha had a tribal structure where leadership was passed down through the father's side. Children belonged to their father's family group. So, there was no place in the tribe for a child whose father was European or American. This was unless the person was officially adopted by a male member of the tribe.

Dr. Charles Charvat wrote about a passage from The Omaha Tribe. It said that because of business and government involvement, two types of chiefs appeared in Indian tribes. One type was called "regular chiefs." They got their position through family inheritance or by being adopted by a former chief. The second type was known as "paper chiefs." They usually had a document that gave them official favor outside the tribe. It is likely that Logan Fontenelle gained influence as the United States interpreter. Then, through his own efforts and skills, he gained respect. This made him a de facto (in fact) chief.

Legacy

Logan Fontenelle is honored in the names of several places and with a monument:

- Fontenelle Forest in Bellevue

- Fontanelle in Washington County, Nebraska

- Fontanelle in Adair County, Iowa

- Logan Creek (in the Omaha language, "Taspóⁿhi báte wachʰíshka") is a stream. It flows through Cedar, Dixon, Thurston, Cuming, Burt, and Dodge counties in Nebraska.

- Fontenelle Boulevard in Omaha was meant to lead drivers to the town of Fontanelle, Nebraska.

- The Hotel Fontenelle, a large hotel in Omaha, was built in the early 1900s.

- Logan Fontenelle Housing Project, Omaha

- The Fontenelle Elementary School in Omaha, and the Logan Fontenelle Middle School in Bellevue.

- A monument was built for Logan Fontenelle in Petersburg, Nebraska. It is near where he died.

- Fontenelle Park is at the corner of Fontenelle Boulevard and Ames Avenue in North Omaha.

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |