Guillaume Delisle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Guillaume Delisle

|

|

|---|---|

Guillaume Delisle portrayed by Konrad Westermayr, 1802

|

|

| Born |

Guillaume Delisle

28 February 1675 |

| Died | 25 January 1726 (aged 50) Paris

|

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | cartographer |

Guillaume Delisle, also known as Guillaume de l'Isle, was a famous French mapmaker. Born in Paris on February 28, 1675, he became well-known for creating very accurate maps of Europe and the recently explored Americas. He passed away in Paris on January 25, 1726.

Contents

Early Life and Learning to Make Maps

Guillaume Delisle was the son of Claude Delisle, who was also a respected scholar. His father taught history and geography and was a tutor to important people, including the Duke Philippe d’Orléans, who later ruled France for a time. Guillaume and two of his half-brothers, Joseph Nicolas and Louis, also became scientists.

Guillaume showed great talent for mapmaking from a young age. He helped his father by drawing maps for his history books. To get even better, Guillaume studied with a famous astronomer named Jean-Dominique Cassini. He quickly started making high-quality maps, with his first important one being the Carte de la Nouvelle-France et des Pays Voisins in 1696.

Guillaume Delisle's Career as a Mapmaker

When Delisle was 27, he became a member of the French Académie Royale des Sciences. This was a special group of scientists supported by the French government. After joining, he signed his maps as "Géographe de l’Académie" (Geographer of the Academy).

His career grew even more successful. In 1718, he received the important title of Premier Géographe du Roi (First Geographer to the King). This meant he was the official mapmaker for King Louis XIV’s son, the Dauphin, and received a salary for teaching him geography.

Delisle was known for making maps without traveling himself. He worked from his office, using information from many different sources. Because of his family's good reputation, he got access to the latest reports from travelers returning from new lands. Being part of the Académie also helped him stay updated on new discoveries in astronomy and measurements. If he wasn't sure about a piece of information, he would clearly note it on his maps. For example, on his Carte de la Louisiane, he marked a river that someone claimed to have discovered, but he added a warning that it might not really exist.

Delisle was very serious about accuracy. In 1700, he even took another mapmaker, Jean-Baptiste Nolin, to court. Delisle accused Nolin of copying secret map information from one of his special globes. Delisle won the case, proving that Nolin had used his work without permission. This showed that Delisle's maps were based on the newest and most accurate knowledge, unlike some other mapmakers who still used old information.

What Happened After Delisle's Death

After Guillaume Delisle died in 1726, his wife tried to keep his mapmaking business going. His brothers, Joseph-Nicolas and Louis, had already moved to Russia to work for Peter the Great. The Delisle workshop was eventually given to another mapmaker named Philippe Buache.

Later, in the late 1700s, a Dutch mapmaker named Jan Barend Elwe republished many of Delisle's maps.

Famous Maps by Guillaume Delisle

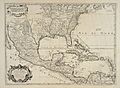

Mapping the Louisiana Territory

Delisle's 1718 map, Carte de la Louisiane et du Cours du Mississippi, is a great example of French mapmaking at its best. This map was very popular and was used as a base for many other maps for years. It showed the lower Mississippi River and the areas around it very accurately.

The map focused on the Mississippi River and the middle part of what is now the United States. It stretched from Lake Superior in the north down to where the Rio Grande meets the Gulf of Mexico in the south. It also went from the Atlantic coast, where many European settlements were, all the way west to the Rocky Mountains.

This map was full of details. It showed where different Indian tribes lived and marked English colonies. Hundreds of labels named lakes, rivers, cities, forts, and mountains. The map also had drawings of animals, ships, and cities, with symbols explained in a key at the bottom. It even showed the routes of explorers like Fernando de Soto and Louis de Moscoso. A compass on the map pointed to true north, suggesting it was more for understanding geography than for sailing.

The map didn't have much detail for the Carolina region and showed the Appalachians extending too far north. The largest area on the map was "La Louisiane," or Louisiana, showing it as a strong French colony. It highlighted important waterways and copper mines that could help trade. This map was also political, showing explorers' paths and French claims to land in the New World.

The map made the British and Spanish areas look smaller than the French ones, even though France had fewer people living in the middle of the continent at the time. It pushed the British border further east than the Appalachian mountains. The British were angry because the map claimed the Province of Carolina was named after a French king, Charles IX, not England's Charles II. This caused a political argument between England and France that lasted for about 15 years.

Delisle's map also claimed French territory all the way to the Rio Grande and Pecos River, which made Spain very upset. Spanish mapmakers then started making their own maps of their lands, which they had previously kept secret. Just months after Delisle's Louisiana map was published, King Louis XV gave him the special title of premier geographe du roi with a good salary.

The 1718 Delisle map was important because it marked a big change in mapmaking. It moved away from old Greek traditions and focused more on science. Delisle used astronomical measurements and carefully checked his information. This map helped set the stage for later 18th-century maps that relied on science and showed the ambitions of empires.

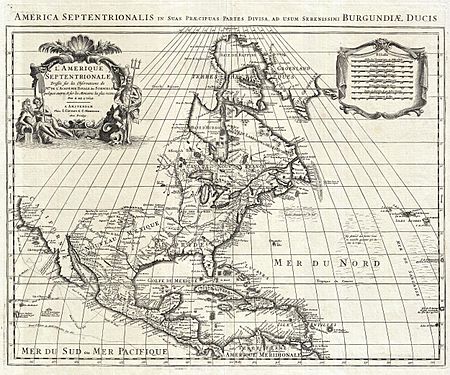

Mapping New France

Delisle's 1703 map, Carte du Canada ou de la Nouvelle France, is famous for being the first map to correctly show the latitude and longitude of Canada. Delisle never visited the New World himself. Instead, he spent seven years doing deep research. He made many early sketches using information from the Jesuit Relations (reports from missionaries) and talked to many missionaries and explorers. This helped him learn a lot about the land. He also used calculations from eclipses to find the exact longitude of Quebec, which had only been guessed at before.

The research and scientific approach behind this map made it a standard for future maps. When it was published, it showed how strong France was in New France in the early 1700s. It was an early example of a more scientific map, different from the less precise maps of earlier times.

The map was very detailed, covering huge areas like New France, Greenland, Labrador, Hudson Bay, Baffin Bay, and the Great Lakes. Delisle chose to leave blank spaces where he didn't have enough information, which was a new and scientific approach for mapmaking in France. Even with these blank areas, Delisle's 1703 map still included a lot of information from Indians and showed imperial claims. For example, Lake Winnipeg was shown with its connection to Hudson Bay, based on an Indian report, not a European discovery.

The map had a large decorative box, called a cartouche, in the upper left corner. This box showed scenes from the New World that hinted at French claims to the land. The cartouche was made by artist N. Guerard and included symbols of French royalty. It also showed a Jesuit missionary baptizing an Indian, and a Recollects missionary guiding Indians. There were also images of two Iroquois men, a Huron holding rosary beads, and a beaver. This showed that even though the map was very scientific, it still had political messages.

Mapping Persia

Delisle also created a map of Iran (Persia) in 1724, showing the country at the end of the Safavid period. This map, called Carte de Perse in French, stretched from the Sea of Azov and the Crimea in the west to Kashmir and Kabul in the east. In the north, it reached the highest point of the Caspian Sea, and in the south, it covered the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz. The map clearly labeled the Persian Gulf as Golfe Persique.

This map included areas that are now many different countries, such as Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, Kuwait, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. It also showed parts of modern-day Russia, Pakistan, Turkey, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and the Arabian Peninsula. Delisle drew mountains and roads connecting cities on this map.

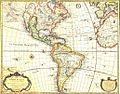

Images for kids

-

Comanche range

Legacy and Places Named After Delisle

Several places are named after Guillaume Delisle. Delisle Inlet in Antarctica is one example. In the United States, Bayou DeLisle and DeLisle, Mississippi are also named in his honor.

Gallery

International Maps

See also

In Spanish: Guillermo Delisle para niños

In Spanish: Guillermo Delisle para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |