Kutenai facts for kids

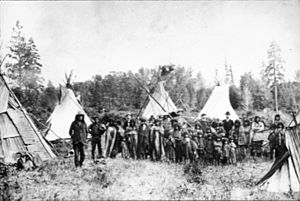

Kutenai group c. 1900

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,536 (2016) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Idaho, Montana), Canada (British Columbia) | |

| 940 | |

(Idaho, Montana) |

596 |

| Languages | |

| English, Kutenai (Kitunahan), ʔa·qanⱡiⱡⱡitnam (Ktunaxa Sign Language) | |

| Religion | |

| Kutenai spiritualism | |

The Kutenai (also called Ktunaxa, Ksanka, Kootenay in Canada, and Kootenai in the United States) are an indigenous people living in Canada and the United States. Kutenai groups live in southeastern British Columbia, northern Idaho, and western Montana. Their language, Kutenai, is unique. It is not related to any other known language.

Four groups form the Ktunaxa Nation in British Columbia. The Ktunaxa Nation has historically been close to the Shuswap Indian Band. This was due to tribal connections and intermarriage. In the U.S., two federally recognized tribes represent Kutenai people. These are the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho and the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in Montana. The Montana group also includes Bitterroot Salish and Pend d'Oreilles bands.

Contents

About the Kutenai Name

Since 1820, about 40 different ways of spelling Kutenai have been used. Two spellings are common today. Kootenay is used in British Columbia. This includes the name of the Lower Kootenay First Nation.

In Montana and Idaho, Kootenai is the spelling. This is used by the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho and the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. These spellings are also used for places on each side of the Canadian-U.S. border. A good example is the Kootenay River, which is called the Kootenai River in the United States.

Kutenai is the spelling often used in books and studies about the people. Kutenai people in both countries have adopted it as a common international spelling. The name likely comes from the Blackfoot word Kotonáwa. This word itself might come from the Kutenai term Ktunaxa.

In the Kutenai language, there are two words for the people and their language: Ktunaxa and Ksanka. Ktunaxa is the main word for the groups in British Columbia. Some think this name means "to go out into the open." Others believe it means "to eat lean meat." The Montana people use the word Ksanka.

Kutenai Communities

Four Kutenai groups live in southeastern British Columbia. One group lives in northern Idaho. Another lives in northwestern Montana.

- The Ktunaxa Nation Council (KNC) represents the four Canadian groups.

- Akisqnuk First Nation ("place of two lakes"). This is an Upper Kutenai group. They are based in Akisqnuk, south of Windermere. Their population is 264.

- Lower Kootenay Band (Yaqan Nukiy). This is a Lower Kutenai group. They are based in Creston. Their population is 214.

- St. Mary's First Nation (ʔaq̓am, "deep dense woods"). This is an Upper Kutenai group. They live near Cranbrook. Their population is 357.

- Tobacco Plains Indian Band (ʔa·kanuxunik, "People of the place of the flying head"). This is an Upper Kutenai group. They live near Grasmere. Their population is 165.

The Shuswap Indian Band was once part of the Ktunaxa Nation. They are a Secwepemc (Shuswap) group. They settled in Kutenai territory in the mid-1800s. They became part of the Ktunaxa and married into their families. They also spoke the Kutenai language. In 2004, they left the Ktunaxa Nation. They are now part of the Shuswap Nation Tribal Council. Their population is 244.

- Kootenai Tribe of Idaho (ʔaq̓anqmi). This is a Lower Kutenai group. They live on the Kootenai Indian Reservation in Boundary County. Their population is 75.

- Kootenai (K̓upawiȼq̓nuk or Ksanka) are part of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. This group also includes Bitterroot Salish and Pend d'Oreilles bands. This is an Upper Kutenai group. They mostly live on the Flathead Reservation. About 6,800 people live on the reservation. Another 3,700 live nearby.

Kutenai History

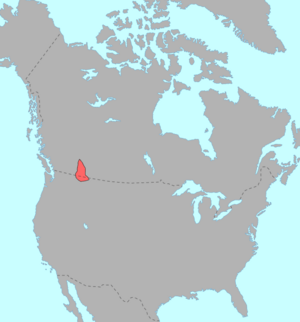

Today, the Kutenai live in southeastern British Columbia, Idaho, and Montana. They are generally split into two groups: the Upper Kutenai and the Lower Kutenai. These names refer to the parts of the Kootenay River where they live. The Upper Kutenai include the Akisqnuk First Nation, St. Mary's Band, and Tobacco Plains Indian Band in British Columbia. They also include the Montana Kootenai. The Lower Kutenai are the Lower Kootenay First Nation of British Columbia and the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho.

Where the Kutenai Came From

Scholars have many ideas about where the Ktunaxa came from. One idea is that they first lived on the prairies. They may have been pushed across the Rockies by the Blackfoot people. Or they might have moved because of famine and disease. Some Upper Kootenay lived like Plains Native people for part of the year. They crossed the Rockies to hunt bison. They often had conflicts with the Blackfoot over food.

Some Ktunaxa stayed on the prairies all year. They had a settlement near Fort Macleod, Alberta. This group suffered greatly from Blackfoot attacks and smallpox epidemics. With fewer people, these Plains Ktunaxa returned to the Kootenay region of British Columbia.

Some Ktunaxa say their ancestors came from the Great Lakes region of Michigan. But so far, no old artifacts or historical records support this story.

The Ktunaxa land in British Columbia has some of the oldest human-made items in Canada. These items are about 11,500 years old. It is not known if these items were made by Ktunaxa ancestors or another group. People have lived in the Kootenay Rockies for a long time. This is shown by old sites where people dug for stone and shaped tools. These tools were often made from quartzite and tourmaline.

The oldest group of artifacts is called the Goatfell Complex. It is named after the Goatfell region near Creston, British Columbia. These tools have been found at quarries in Goatfell, Harvey Mountain (Idaho), and other places. All these sites are within 50 km of Creston.

Archaeologist Dr. Wayne Choquette believes these artifacts show that people have lived in this area continuously for 11,500 years. He also thinks the tool-making methods were local. There is no proof that the first people left or were replaced by others. Dr. Choquette believes today's Ktunaxa are descendants of these first inhabitants.

Other scholars, like Reg Ashwell, suggest the Ktunaxa moved to British Columbia in the early 1700s. They may have been harassed by the Blackfoot from east of the Rockies. He notes their language is different from coastal Salish tribes. Also, their traditional clothing, customs (like using teepees), and religion are more like Plains peoples.

The Goatfell artifacts suggest that before 11,500 years ago, the people who came to the Kootenay mountains might have lived in the southwestern United States. This was when British Columbia was covered by a large ice sheet. The tools found are similar to those from the North American Great Basin during the late Pleistocene ice age. The idea is that as the glaciers melted, people moved north. They followed the plants and animals that returned to the land.

From the first Ktunaxa settlement in the Kootenays until the late 1700s, little is known about their social and political life. Stone tools became more complex. They were likely big game hunters in their earliest times. The Ktunaxa were first mentioned on Alexander Mackenzie's map around 1793.

As the weather got warmer, the glacial lakes drained. Fish found homes in the warmer waters. The Lower Kootenay people made fishing a key part of their food and culture. They also kept their old traditions of hunting.

Early Kutenai Life

People started studying the Ktunaxa in the mid-1800s. What these European and North American scholars wrote should be read carefully. They sometimes added their own cultural ideas to what they saw. But their writings give us the most detailed descriptions of Ktunaxa life. This was a time when Native ways of life were changing fast due to European settlement.

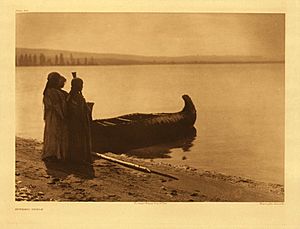

The earliest studies describe Ktunaxa culture around 1900. Europeans saw the Ktunaxa as having a stable economy and rich social life. Their economy focused on fishing, using fish traps and hooks. They traveled on waterways in the sturgeon-nosed canoe. They also hunted seasonally for bear, deer, caribou, and many birds. As mentioned, the Upper Kootenay often crossed the Rockies to hunt bison. But the Lower Kootenay did not hunt bison as it was not important to their way of life.

The Ktunaxa had vision quests, especially for young men becoming adults. They used tobacco in rituals. They performed a Sun Dance and Grizzly Bear Dance. They also had a midwinter festival and a Blue Jay Dance. Men belonged to different groups or lodges, like the Crazy Dog Society. These groups had duties in battle, hunting, and helping the community.

The Ktunaxa and their neighbors, the Sinixt, both used the sturgeon-nosed canoe. This boat was first described in 1899. It was noted to be similar to canoes used in Asia. At the time, some scholars thought that if cultures had similar things, one must have copied the other. Now, most scholars believe many new ideas developed on their own in different cultures.

Harry Holbert Turney-High wrote a detailed study of the Ktunaxa. He described how they harvested bark for the canoe:

A tree ... growing rather high in the mountains is sought. Finding one of the desired size and quality, a man climbed it to the proper height and cut a ring around the bark with his elk-horn chisel or flint knife. In the meantime a helper cut out another ring at the base of the tree. This done, an incision was made down the length of the trunk connecting the two rings. This cut had to be as straight and accurate as possible. A stick of about two inches in diameter was used carefully to pry the bark from the tree. The bark was wrapped up so that it would not dry out on the way to camp. The inside, or tree-side of the bark sheet, became the outside of the canoe, while the outside surface became the inside of the boat. The bark was considered ready for immediate use. There was no scraping or seasoning, nor was it decorated in any way.

Christian missionaries came to Ktunaxa lands to convert the people. They kept many written records of their work and what they saw. Because of this, we know more about the missionary process than other parts of Ktunaxa history from that time.

The Ktunaxa learned about Christianity as early as the 1700s. A Lower Kootenay prophet named Shining Shirt shared news of the 'Blackrobes' (French Jesuit missionaries). Ktunaxa people also met Christian Iroquois sent west by the Hudson's Bay Company. By the 1830s, the Ktunaxa began to mix some Christian ideas into their ceremonies. They were influenced more by Christian Native people from other areas than by European missionaries.

Father Pierre-Jean de Smet was the first missionary to visit the region in 1845-46. He wanted to set up missions for Native peoples. The Catholic Jesuits wanted to help these newly found peoples in the New World. While missionaries had been in Eastern North America for 200 years, the Ktunaxa were not a focus until the mid-to-late 1800s. After De Smet, a Jesuit named Philippo Canestrelli lived among the Ksanka people of Montana in the 1880s and 90s. He wrote a famous grammar of their language, published in 1896. The first missionary to stay permanently in the Yaqan Nu'kiy territory (Creston Band of Lower Kootenay) was Father Nicolas Coccola. He arrived in 1880. His memories, along with newspaper reports and Ktunaxa oral stories, tell us about Ktunaxa history in the early 1900s.

When Europeans first came to Ktunaxa lands, mainly due to a gold rush in 1863, the Ktunaxa were not very interested in European ways of making money. Traders tried to get them to trap for the fur trade. But few Lower Kootenay found this worthwhile. The Lower Kootenay region had plenty of fish, birds, and large game. Since the Yaqan Nu'kiy had a secure way of life, they resisted new economic activities.

Slowly, the Yaqan Nu'kiy began to join European industries. They worked as hunters and guides for miners at the Bluebell silver-lead mine. The richest gold mine ever found in the Kootenays was discovered by a Ktunaxa man named Pierre. He and Father Coccola claimed it in 1893.

The 20th Century and Beyond

Sometimes there were disagreements between the Yaqan Nu'kiy and the settlers in Creston. But mostly, they lived peacefully together. Their conflicts were usually about land use. In contrast, relations between the Lower Kootenay and the European society in Bonners Ferry, Idaho, became worse.

By 1900, some Yaqan Nu'kiy started farming like European settlers. But their way of using the land was different. For example, a newspaper article from 1912 described a conflict over cutting hay:

A dispute over the rights to cut hay on the flat lands, between the Indians and the white men, which might have resulted in bloodshed, was settled Wednesday by W.F. Teetzel, government agent, of Nelson, who told both Indians and whites that if violence is done, no one would be allowed to cut hay on government land. ... The principal trouble this year occurred when some Indians threatened Frank Lewis and drove him from the hay he had already cut. The Indians claim they have cut land at this particular place for years while the old-time ranchers say that hay has never before been cut there. ... Mr. Teetzel arrived from Nelson Wednesday and in conference with Chief Alexander, got him to promise to see that Mr. Lewis got his hay, and warned him to keep the Indians from violence under penalty of losing the right of cutting hay on the flats. This warning he also gave to the white men. This is not the only one of the cases occurring this year. One farmer whose place is located near the reservation has been continually bothered by the Indians cutting his fences and turning their cattle in to graze on his property.

Another newspaper report from June 1912 said: "[Indian Agent Galbraith] says everything is in good condition and the majority of the Indians are at work picking berries for the ranchers who find their help useful and profitable."

These examples show the relationship between two peoples. The Ktunaxa's lands were greatly reduced by the reserve system. European settlers constantly wanted to expand their access to land and industries.

During the 1900s, the Yaqan Nu'kiy slowly became involved in all the industries of the Creston valley. These included agriculture, forestry, mining, and later health care, education, and tourism. This process of joining new industries changed the Yaqan Nu'kiy's traditional ways of life. Yet, they have remained a successful and confident community. They slowly gained more control and self-government. The government's Department of Indian Affairs became less involved. Like most tribes in British Columbia, the Yaqan Nu'kiy did not have a treaty defining their land rights. For decades, they have been working with the government of Canada on treaty negotiations. Today, the Creston Band of the Ktunaxa has 113 people living on the reserve. Many others live off-reserve and work in various industries in Canada and the United States.

The Ktunaxa feel they have lost some important traditions. They are now working to bring back their culture. They especially want to encourage language study. Only about 10 people in the U.S. and Canada speak Ktunaxa fluently. The Yaqan Nu'kiy have created a language program for grades 4–6. They have been teaching it for four years to help a new generation learn the language. They are also designing lessons for grades 7–12. This requires meeting British Columbia's school guidelines. At the same time, they are recording oral stories and myths. They are also videotaping their traditional crafts and technologies with spoken instructions.

The "Kootenai Nation War"

On September 20, 1974, the Kootenai Tribe, led by Chairwoman Amy Trice, declared war on the United States government. Their first action was to place tribal members on each end of U.S. Highway 95. This highway runs through Bonners Ferry. They asked drivers to pay a small fee to drive through what had been the tribe's original land. About 200 Idaho State Police were there to keep peace, and there was no violence. The tribe planned to use the money to house and care for elderly tribal members. Most tribes in the United States cannot declare war on the U.S. government because of treaties. However, the Kootenai Tribe had never signed a treaty.

The United States government eventually gave the tribe 12.5 acres (0.051 km²) of land. This land became the basis of the Kootenai Reservation. In 1976, the tribe issued "Kootenai Nation War Bonds" that sold for $1.00 each. The bonds were dated September 20, 1974. They included a short declaration of war on the United States. These bonds were signed by Amelia Custack Trice, Tribal Chairwoman, and Douglas James Wheaton, Sr., Tribal Representative.

Literature

- Boas, Franz, and Alexander Francis Chamberlain. Kutenai Tales. Washington: Govt. Print. Off, 1918.

- Chamberlain, A. F., "Report of the Kootenay Indians of South Eastern British Columbia," in Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, (London, 1892)

- Finley, Debbie Joseph, and Howard Kallowat. Owl's Eyes & Seeking a Spirit: Kootenai Indian Stories. Pablo, Mont: Salish Kootenai College Press, 1999. ISBN: 0-917298-66-7

- Linderman, Frank Bird, and Celeste River. Kootenai Why Stories. Lincoln, Neb: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. ISBN: 0-585-31584-1

- Maclean, John, Canadian Savage Folk, (Toronto, 1896)

- Tanaka, Beatrice, and Michel Gay. The Chase: A Kutenai Indian Tale. New York: Crown, 1991. ISBN: 0-517-58623-1

- Turney-High, Harry Holbert. Ethnography of the Kutenai. Menasha, Wis: American Anthropological Association, 1941.

See also

In Spanish: Kutenai (tribu) para niños

In Spanish: Kutenai (tribu) para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |