Sinixt facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 250 in the US | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Canada (British Columbia) United States (Washington) |

|

| Languages | |

| English, Salishan, Interior Salish | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Colville, Sanpoil, Nespelem, Palus, Wenatchi, Entiat, Methow, Southern Okanagan, Sinkiuse-Columbia, and the Nez Perce of Chief Joseph's band |

The Sinixt people are also known as the Sin-Aikst or Arrow Lakes Band. They are a First Nations group from Canada. The Sinixt come from Indigenous peoples who have lived for at least 10,000 years in what is now the West Kootenay area of British Columbia, Canada. They also lived in nearby parts of Eastern Washington in the United States.

The Sinixt speak a special dialect called sn-selxcin. It is part of the Colville-Okanagan language family. Today, many Sinixt live on the Colville Indian Reservation in Washington. They are part of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, which is a recognized American Indian Tribe by the U.S. government.

Many Sinixt still live in their traditional lands in Canada, especially in the Slocan Valley. However, the Canadian Government officially said the Sinixt were "extinct" in 1956.

Template:TOC limit=3

Contents

Sinixt History and Way of Life

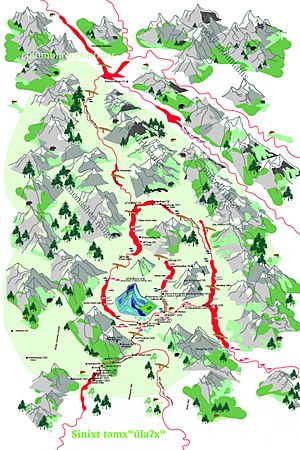

Traditional Lands of the Sinixt

The Sinixt lived along the Columbia River, Arrow Lakes, Slocan Valley, and parts of Kootenay Lake. Other tribes used the Columbia River for trade. They would travel through Sinixt lands to trade with the Sinixt and other groups further south.

Today, some parts of the Sinixt's traditional lands are also claimed by the Westbank First Nation (part of the Okanagan people) and the Ktunaxa people. There is some disagreement about who historically used these areas.

Daily Life in the Past

In the early 1800s, there were about 3,000 Sinixt people. They lived in different groups, which were good for hunting and fishing. Some Sinixt lived around the Arrow Lakes, while others lived in the Northport and Kettle Falls areas in Washington State. When they got horses, they could travel further east to hunt on the Great Plains.

Long ago, the Sinixt lived in warm, underground houses during the winter. In the summers, they fished, hunted, and gathered food. They found food in their homeland of mountains and lakes. They spent winters in sheltered valleys and summers by the Columbia River. The Sinixt were known as "complex collectors" because of their advanced ways of gathering food.

Some stories and historical records suggest the Sinixt were seen as the "Mother Tribe" of the Pacific Northwest Salish groups. This meant they often helped settle arguments between other tribes.

Early explorers described the Sinixt as average height with hazel eyes. They were skilled at building bridges over the Columbia River and were very good at fishing.

What the Sinixt Ate

The Sinixt ate many different foods. Their main foods included huckleberries, salmon, and roots like camas and bitterroot. They also ate black moss, other berries (like serviceberry, gooseberry, and foam berry), hazelnuts, wild carrots, and peppermint.

They hunted animals such as deer, elk, moose, caribou, rabbit, mountain sheep, mountain goat, and bear. After horses arrived, they also hunted bison. They chewed pine pitch like gum and used many herbal medicines.

In June, salmon would arrive at Kettle Falls, which was the southern edge of Sinixt land. The Sinixt only caught salmon that were not strong enough to get over the falls. This made sure the strongest salmon could go on to lay their eggs. In August, both groups of Sinixt traveled to Red Mountain in British Columbia to pick huckleberries. These seasonal events were very important to their culture.

Hunting and Travel

The Sinixt who lived further north trained dogs to help them hunt deer. The dogs would chase deer toward the Columbia River. Hunters in canoes would then shoot the deer with bows and arrows.

The Sinixt used a special type of canoe called a Sturgeon-nosed canoe. These canoes were about 15–17 feet (4.5–5 meters) long. They had a cedar frame covered with large pieces of pine bark. They rode low in the water with tips that sloped downwards to cut through the wind.

The Sinixt often married people from the Swhy-ayl-puh (Colville) tribe. Their languages were very similar. The Colville people lived mostly in the Colville Valley. Their land met Sinixt land at Kettle Falls.

Family and Education

Sinixt children were watched closely by elders. Young children went on short trips to find protective spirits. They had to bring back an object to prove they made the journey. As they grew older, these trips became longer. Each person was expected to find many spirits, as each spirit had different powers.

Around age six, children learned tribal legends and family history. They also learned about tribal customs and laws. At eight or nine, they learned to swim and run long distances. Boys learned to make and use weapons and fishing gear. Girls learned about plants, how to prepare animal hides, care for young children, maintain homes, and cook meals.

Sinixt religion focused on gaining power from nature. The sun, stars, water, and different animals (especially salmon and coyote) were believed to have special powers.

The entire tribe was led by one main chief (ilmi wm). Each smaller village of 50-200 people had a local chief, called a "thinker." These "thinkers" would meet to form a council.

The Sinixt were a Matrilocal people. This meant that when a couple married, they lived with the wife's family.

Challenges Before Europeans Arrived

Historical records show that the Sinixt population greatly decreased because of smallpox epidemics. These happened before Scottish and Métis fur traders from the North West Company arrived. The epidemic of 1781 was very severe, killing up to 80% of the people. Early explorers like David Thompson saw the scars on older Sinixt people and heard stories about the disease.

The Sinixt were also affected by big changes before Europeans came. The Ktunaxa people, who lived east of the Sinixt, were pushed further into the mountains by the Blackfoot. The Blackfoot had taken control of Ktunaxa land. The Ktunaxa and Sinixt sometimes fought over land along the lower Kootenay River. The Sinixt later made peace with the Ktunaxa. They also joined other tribes like the Kalispel, Flathead, Coeur d'Alene, Spokane, and Nez Perce to fight against the Blackfoot.

Fur Trade and Missionaries

The Sinixt and their allies had a very close relationship with the Hudson's Bay Company. They spent winters near the main trading post at Colville starting in 1830. The Sinixt helped the company stop American trappers and settlers from entering their land. The Sinixt were very active fur traders at Fort Colvile.

In 1837, Jesuit missionaries came to the area. St. Paul's Mission at Kettle Falls was built with help from Colville and Sinixt workers. In the 1840s, the Sinixt population dropped sharply from about 3,000 to 400. This was due to diseases and people taking their land. Also, the salmon runs began to shrink because of commercial fishing near the mouth of the Columbia River. Some Sinixt people felt their traditional religion was failing. Chief Kin-Ka-Nawha, a Sinixt leader, was one of those who became a Catholic.

One People, Two Countries

In 1846, the United States took control of the Oregon Country south of the 49th Parallel. Some Sinixt stayed in American territory near Kettle Falls. Kettle Falls was the southern border of Sinixt land and was shared with the Colville people. The two tribes were traditionally close. They celebrated the Sinixt's arrival at the falls during fishing season with a three-day dance.

After the border was set, the Hudson's Bay Company built Fort Shepherd, British Columbia in Canada. This was to serve their old customers and keep a post in British territory. Sinixt land in British Columbia remained theirs. Even in the 1860s, Sinixt leaders believed British ownership in their northern land meant Sinixt control. When Fort Shepherd was left by the Hudson's Bay Company, it was left in Sinixt hands.

Gold and Silver Rushes

Miners began entering Sinixt territory in British Columbia in the 1850s and 1860s. The Sinixt were able to keep control over their northern lands through the 1870s, even with some conflicts. They often worked with white settlers but continued to claim ownership in British Columbia. They sometimes used force to resist American miners. In 1865, the Sinixt stopped 200 miners at the Columbia and Kootenay rivers. They wanted to protect their hunting and fishing rights, which the Crown had promised.

However, with fewer Sinixt people, they could not control the area when many more miners arrived in the 1880s and 1890s. Many new towns appeared in the West Kootenay and Boundary Country areas. Most Sinixt continued to live in Washington State on the Colville Reservation. Still, some Sinixt stayed in Canada during the first half of the 1900s. Many others also returned to their ancestral land in British Columbia to hunt and fish in the summers.

Kin-Ka-Nawha stepped down as chief when he was old. Joseph Cotolegu took over, with Andrew Aorpaghan (Chief Edwards) and James Bernard as subchiefs. They would later become leaders themselves.

Colville Confederated Tribes

In the U.S., the Colville Confederated Tribes were officially formed in 1872. They were forced to live on the Colville Reservation. At this time, the name Sinixt or Sin Aikst was changed to Lakes by the U.S. government.

At first, the Confederated Tribes were given a reservation east of the Columbia River. But three months later, it was taken away because white settlers wanted it. They were given a similar-sized piece of land on the west side of the river, but it was not as good. This reservation first went all the way to the Canada–US border. However, the northern half was taken away in 1892. This separated it from Sinixt traditional land in British Columbia. As more tribes lost their land, the shrinking reservation had to take in even more people. They also had to deal with miners and settlers like the Doukhobors, who arrived from Russia in 1912.

In 1900, Aropaghan agreed to divide the land into individual plots instead of holding it in common. He also agreed to include "half breeds" equally in the land sharing.

Bernard traveled three times to Washington, D.C. to speak for his people. He went in 1890 as an interpreter for Chief Smitkin of the Colvilles. In 1900, he went with Chief Lot and Chief Barnaby to discuss the reservation borders. His last trip was in 1921, as the head of a group from the Confederated Tribes.

Grand Coulee Dam and Its Impact

Until the Grand Coulee Dam was built, the Lower Sinixt continued to fish at Kettle Falls in their traditional way. They kept electing a Salmon Chief. They used baskets on poles to catch salmon that could not get over the falls. They also used spears with tips that could come off, like a harpoon.

The dam changed everything for the Colville and Lakes people. When the dam was built, the great salmon runs ended. This stopped a tradition that had lasted for hundreds of years. After this, there was often not enough food. The groups of people spread out. The dam's rising waters also covered the Sinixt community of Inchelium, Washington. This community had to move, which further changed their traditional way of life.

Return to Canada

In her book, Keeping the Lakes Way, author Paula Pryce shares stories from Sinixt elders in Washington State. They talked about visiting "the Northern Territory" in Canada even after the Sinixt were declared extinct. They went to pick berries, trade fish, and visit sacred places.

A permanent Sinixt presence was re-established in British Columbia in the late 1980s. Following an Elder's guidance, some Sinixt descendants returned to the Slocan Valley. They protested road building that affected an important village site, now called the Vallican Heritage Site. A bridge being built at Vallican meant a road was placed very close to a large pit-house village and ancient burial site. Since 1989, Sinixt people have continued to live in the Slocan Valley. Local members help with returning human remains to their proper resting places and are becoming more involved in local matters.

Archaeological Discoveries

Recent archaeological work has shown that the Sinixt had a complex society. This matches historical accounts and Sinixt stories of an advanced society. Pithouses in the Slocan Valley are some of the earliest very large houses of this type. Some were over 20 meters (66 feet) wide. The Slocan Narrows site also had some of the most recent very large pithouses. This and other evidence shows that the Sinixt society was one of the most complex in the entire region.

Sadly, major hydroelectric projects along the Columbia and Kootenay rivers flooded many Sinixt burial grounds and most village sites. This prevented archaeologists from studying these important historical areas.

Sinixt Status Today

The Sinixt today mostly live on the Colville Indian Reservation in Washington. They are part of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, which is recognized as an American Indian Tribe.

Legal Extinction in Canada

Some Sinixt people live in their traditional territory on the "Canadian side" of the border. They are mainly in Vallican in the Slocan Valley. They are not recognized by the Canadian Government. Canada officially declared them "extinct" in 1956 under the Indian Act.

In 1995, Ron Irwin, who was the Minister of Indian Affairs, said that "The Arrow Lakes Band ceased to exist as a band for the purpose of the Indian Act... It does not, however, mean that the Sinixt ceased to exist as a tribal group." This means the government stopped recognizing them as a "band" but not as a people.

At the time Canada declared them extinct, there were more than 250 Sinixt in Washington State. Other Sinixt descendants had moved to the Canadian part of the Okanagan region or joined the Spallumcheen Indian Band (part of the Secwepemc people).

Land Claims in Canada

Members of the Sinixt Nation are fighting this "extinction." They are working to get back their land rights in British Columbia, where about 80% of their ancestral territory is located.

Another challenge is that the Ktunaxa people also claim some of the same traditional territory. The Ktunaxa Nation is currently working on a treaty with the Canadian and British Columbia governments for this region. This includes the lower Kootenay River valley around Castlegar and Nelson, and all lands within the curve of the Columbia River north to Mica Dam and the entire Slocan Valley.

In 1994, Sinixt Spokesperson Marilyn James stated that "Neither our ancestors nor the members of Sinixt Nation have ever given up our rights to any individual, any government or any other organization, including other native tribes or native nations."

Maps from the Okanagan Nation Alliance (which includes the Colville Tribes) do not show Sinixt territory. Instead, they show the region as part of Okanagan traditional territory.

In 2008, the Sinixt Nation Society filed a lawsuit. They claimed aboriginal title to Crown land in the Kootenays. Their lawyer said they want the right to be asked for permission for all uses of Crown land in their territory. Private lands would not be affected.

Sinixt Culture Today

Many Lakes (Sinixt) people believe in living ethically. This means having a balanced relationship with humans, the land, and the spirit world where ancestors live. Elder Eva Orr called this 'keeping the Lakes' way.' This way of life means people should not just take for themselves. Instead, they should give back by being fair, sharing, and living peacefully.

The Sinixt have a strong connection to their traditional territory. This is shown in the wbuplak'n, their highest legal and cultural rule. It outlines their responsibility for all land, water, plants, animals, and cultural resources within Sinixt territory.

Sinixt people in the northern territory have a bi-weekly radio program called Sinixt Radio. It is on the Nelson, B.C. Community Radio station CJLY-FM. The northern Sinixt also host an annual Barter Fair every fall in Vallican, B.C. This event has live music and encourages local Bartering of goods and services.

Recognition of Hunting Rights

On March 27, 2017, the Provincial Court of British Columbia made an important decision. They ruled in favor of Rick DeSautel, a Sinixt member from the Colville reservation. He had a dispute with Canadian authorities about hunting in Canadian territory. This ruling meant that the Sinixt were recognized as having rights in Canada, even though they were declared extinct in 1956.

On May 2, 2019, the BC Court of Appeal supported DeSautel's hunting rights. The Supreme Court of Canada agreed on October 24, 2019, to hear the B.C. government's appeal. On April 23, 2021, the Supreme Court of Canada dismissed the appeal. This upheld Mr. Desautel’s right to exercise Aboriginal rights under section 35 of the Constitution. It also recognized the Lakes Tribe, a modern group of the Sinixt, as an “Aboriginal people of Canada.”

Notable Sinixt People

In Washington, one Sinixt family has become well-known among "urban Indians."

- Bernie Whitebear (1937–2000) was an activist for Native American rights in Seattle. He started several "urban Indian" organizations. He was named Washington state's "First Citizen of the Decade" in 1997.

- His sister, Luana Reyes (1933—2001), was a deputy director of the U.S.'s Indian Health Services.

- Their brother, Lawney Reyes (born around 1931), is a sculptor, designer, curator, and author based in Seattle.

Bernie, Luana, and Lawney are descendants of Alex Christian. His family lived at Kp'itl'els (Brilliant, B.C.), a Sinixt village, for many generations. This was until the Canadian Government sold their land to settlers.

Novelist and memoirist Mourning Dove, also known as Christine Quintasket, is described as being of Sinixt-Skoyelpi descent. She wrote about her childhood in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Mourning Dove was one of the first Native American women to publish a novel. She identified herself as Okanogan.

Joe Feddersen is a Sinixt/Okanagan sculptor, painter, photographer, and mixed-media artist. He was born in Omak, Washington.

|

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |