Grand Coulee Dam facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Grand Coulee Dam |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Country | United States |

| Location | Grant / Okanogan counties, Washington |

| Coordinates | 47°57′26″N 118°58′43″W / 47.9572°N 118.9785°W |

| Purpose | Power, regulation, irrigation |

| Status | Operational |

| Construction began | July 16, 1933 |

| Opening date | June 1, 1942 |

| Construction cost | Original dam: $163 million 1943 Third powerplant: $730 million 1973 |

| Operator(s) | Bureau of Reclamation |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | Concrete gravity |

| Impounds | Columbia River |

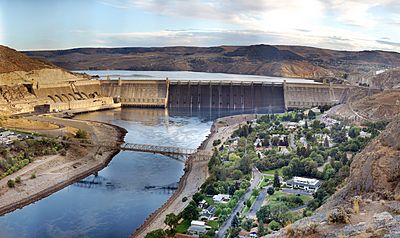

| Height | 550 ft (168 m) |

| Length | 5,223 feet (1,592 m) |

| Width (crest) | 30 ft (9 m) |

| Width (base) | 500 ft (152 m) |

| Dam volume | 11,975,520 cu yd (9,155,942 m3) |

| Spillway type | Service, drum gate |

| Spillway capacity | 1,000,000 cu ft/s (28,317 m3/s) |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | |

| Total capacity | 9,562,000 acre⋅ft (12 km3) |

| Active capacity | 5,185,400 acre⋅ft (6 km3) |

| Catchment area | 74,100 sq mi (191,918 km2) |

| Surface area | 125 sq mi (324 km2) |

| Power station | |

| Commission date | 1941–1950 (Left/Right) 1975–1980 (Third) 1973–1984 (PS) |

| Type | Conventional, pumped-storage |

| Hydraulic head | 380 ft (116 m) |

| Turbines | 33: 27 × Francis turbines 6 × pump-generators |

| Installed capacity | 6,809 MW 7,079 MW (max) |

| Capacity factor | 35% |

| Annual generation | ≈ 21.17 TWh (2022) |

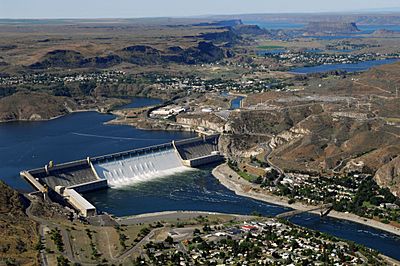

The Grand Coulee Dam is a huge concrete dam on the Columbia River in Washington, USA. It was built to make hydroelectric power and provide water for farming. Built between 1933 and 1942, it first had two powerhouses. A third powerhouse was added in 1974. This made Grand Coulee the largest power station in the United States. It can produce 6,809 MW of electricity.

Building the dam was a big debate in the 1920s. Some people wanted to water the dry Grand Coulee area using a canal. Others wanted a tall dam that could pump water. The dam supporters won in 1933. The first plan was for a "low dam" that was 290 feet (88 m) tall. It would make electricity but not help with irrigation. However, the builders started constructing a "high dam" right away.

In August 1934, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt visited the site. He supported the "high dam" design. This dam would be 550 ft (168 m) high. It would make enough electricity to pump water for irrigation. Congress approved the high dam in 1935. It was finished in 1942. Water first flowed over its spillway on June 1, 1942.

The dam's power helped industries in the Northwest during World War II. A third power plant was built between 1967 and 1974. This was due to more energy needed and a treaty with Canada. Today, the dam has four power stations. They can produce 6,809 MW of power. The dam also provides water for 671,000 acres (2,700 km2) of farmland.

The lake behind the dam is called Franklin Delano Roosevelt Lake. It is named after President Roosevelt. Building the lake meant over 3,000 people had to move. This included Native American families. The dam does not have a way for fish to pass. This means salmon cannot reach the areas upstream.

Contents

How the Dam Idea Started

The Grand Coulee is an old riverbed on the Columbia Plateau. It was formed by glaciers and huge floods long ago. The first idea to water the Grand Coulee with the Columbia River was in 1892. A man named Laughlin McLean suggested building a 1,000 ft (305 m) dam. This dam would be so high that water would flow into the Grand Coulee.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation looked into pumping water from the Columbia River. This water would irrigate farms in central Washington. But a plan to get money for irrigation failed in 1914.

In 1917, a lawyer named William M. Clapp suggested damming the Columbia River. He thought a concrete dam could flood the plateau, like ice did centuries ago. He teamed up with James O'Sullivan and Rufus Woods. They were called the "Dam College." Woods promoted the dam in his newspaper.

Debates Over the Dam

The idea for the dam became popular in 1918. People who wanted to reclaim land in Central Washington split into two groups. The "pumpers" wanted a dam with pumps. These pumps would lift water from the river into the Grand Coulee. From there, canals would water farms. The "ditchers" wanted to bring water from the Pend Oreille River using a canal. This canal would water farms in Central and Eastern Washington.

Many local people, like Woods, were "pumpers." They said the dam's electricity could pay for itself. They also thought the "ditchers" wanted to control all the electricity. The "ditchers" tried to stop the dam. They spread rumors that the dam site was not strong enough. This was later proven false.

In 1925, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers studied the Columbia River. Their report in 1932 suggested building the Grand Coulee Dam. It also said that selling electricity could pay for the dam. The Bureau of Reclamation liked this idea.

President Roosevelt's Support

Some people thought there was no need for more electricity. They also thought there were too many crops already. But the Bureau of Reclamation believed energy demand would grow. President Franklin D. Roosevelt became president in 1933. He supported the dam because it could provide irrigation and power.

However, he was worried about the high cost of $450 million. So, he first supported a "low dam" of 290 ft (88 m). He gave $63 million in federal money. Washington State added $377,000. In 1933, the Columbia Basin Commission was set up. The Bureau of Reclamation was chosen to manage the construction.

Building the Grand Coulee Dam

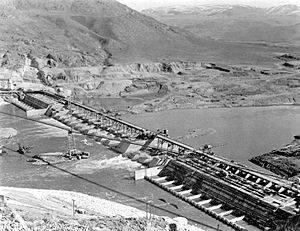

Construction started on July 16, 1933. Workers began digging at the low dam site. The dam was meant to control floods, provide irrigation, and make electricity. The design allowed for the dam to be made taller later.

Early Challenges

Workers and engineers faced many problems. It was hard to find companies big enough to take on the contracts. Native American graves had to be moved. Temporary ways for fish to pass had to be built. Landslides and protecting fresh concrete from freezing were also challenges.

A conveyor belt almost 2 mi (3.2 km) long was built. This helped move dirt and stone. Workers drilled deep holes into the granite. They filled cracks with a special mixture called grout. This made the foundation stronger. Sometimes, excavated areas collapsed. To fix this, pipes were put into the ground and filled with cold liquid. This froze the earth, making it stable for work to continue.

The main contract for the dam was given to a group of three companies. They were called MWAK. Their bid was $29,339,301. This was much lower than other bids.

Building Cofferdams

Two large temporary dams, called cofferdams, were built. They were parallel to the river. This allowed workers to dry parts of the riverbed. They could then start building the dam's foundation. Water continued to flow down the middle of the river.

By the end of 1935, about 1,200 workers finished the west and east cofferdams. In August 1936, parts of the west cofferdam were removed. This let water flow through the dam's new foundation. By December 1936, the entire Columbia River was flowing over the new foundations. People came in large numbers to see the dry riverbed.

Changing the Design to a High Dam

On August 4, 1934, President Roosevelt visited the site. He was very impressed. He said, "I leave here today with the feeling that this work is well undertaken; that we are going ahead with a useful project, and we are going to see it through for the benefit of our country." Soon after, the plan for the high dam was approved.

In June 1935, MWAK joined with another company, Consolidated Builders Inc. They agreed to build the high dam for an extra $7 million. The new design included a pumping plant for irrigation. President Roosevelt saw the dam as part of his New Deal plan. It would create jobs and farming chances. It would also keep electricity prices low. In August 1935, Congress approved funding for the high dam.

First Concrete and Completion

On December 6, 1935, the first concrete was poured. Concrete was brought by train cars. It was mixed and then poured into large columns. To cool the concrete and help it harden, about 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of pipes were placed inside. Cold river water was pumped through these pipes. This cooled the concrete from 105 °F (41 °C) to 45 °F (7 °C).

In January 1936, the permanent Grand Coulee Bridge opened. In March 1938, MWAK finished the lower dam. Consolidated Builders Inc. then started building the high dam. By December 1939, the west power house was done. About 5,500 workers were on site that year.

Between 1940 and 1941, the dam's eleven floodgates were installed. In January 1941, the first generator started working. On June 1, 1942, the reservoir was full. Water flowed over the dam's spillway for the first time. The dam was officially complete on January 31, 1943.

Clearing the Reservoir Area

Starting in 1933, land was bought behind the dam for the future reservoir. This area would become Lake Roosevelt. It flooded 70,500 acres (285 km2) of land. Eleven towns, two railroads, and many roads had to be moved. About 3,000 people had to relocate. This included members of the Colville Confederated and Spokane tribes. Their lands were flooded.

The government bought the land from residents. Many did not want to sell. By 1942, all land was bought for $10.5 million. This included moving farms, bridges, and roads.

In late 1938, workers began clearing 54,000 acres (220 km2) of trees and plants. The cut wood was sold. The clearing sped up in April 1941. It was called a national defense project. The last tree was cut down on July 19, 1941.

Workers and Their Homes

Workers building the dam earned about 80 cents an hour. The dam's payroll was one of the largest in the country. About 8,000 people worked on the project. Frank A. Banks was the chief construction engineer. Building conditions were dangerous, and 77 workers died.

Housing was needed for the workers. The Bureau of Reclamation built Engineer's Town. MWAK built Mason City in 1934. Mason City had a hospital, post office, and electricity. It had 3,000 people. Other living areas, called Shack Town, did not have these services. The city of Grand Coulee also supported workers. In 1956, Mason City and Engineer's Town became the city of Coulee Dam.

Irrigation Pumps

During World War II, making power became more important than irrigation. In 1943, Congress approved the Columbia Basin Project. Construction of irrigation facilities began in 1948. The North Dam and Dry Falls Dam were built. They created Banks Lake, which covered part of the Grand Coulee. Other dams, canals, and siphons were built. This created a huge irrigation system. Irrigation began between 1951 and 1953. Six of the 12 pumps were installed, and Banks Lake was filled.

Expanding the Dam

The Third Powerplant

After World War II, more electricity was needed. This led to plans for another power plant at Grand Coulee Dam. A problem was that the Columbia River's flow changed a lot during the year. Only some generators could run all year.

To make a new power plant work, the river's flow needed to be controlled more. This required water storage projects in Canada. The Columbia River Treaty was signed in 1964. It included agreements for Canada to build dams upstream. This helped make the new power plant possible.

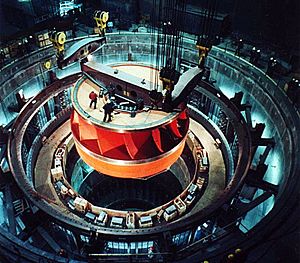

The Third Powerplant was approved in 1966. Between 1967 and 1974, the dam was expanded. This involved tearing down part of the dam and building a new section. The dam became almost a mile long. The new powerhouse had six very large generators. Three 600 MW units and three 700 MW units were installed. The first new generator started in 1975. The last one started in 1980. The 700 MW units were later upgraded to 805 MW.

Pump-Generating Plant

After power shortages in the 1960s, it was decided that the remaining six planned pumps should also generate power. These are called pump-generators. When a lot of energy is needed, they can make electricity. They use water from the Banks Lake feeder canal, which is at a higher level.

The Pump-Generating Plant was finished in 1973. The first two pump-generators started working. By January 1984, all six were running. They added 314 MW to the dam's power capacity. In May 2009, the plant was renamed the John W. Keys III Pump-Generating Power Plant. It was named after John W. Keys III, a former commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation.

Upgrades and Maintenance

A big upgrade of the Third Powerplant started in March 2008. It will continue for many years. This includes replacing old underground cables with new overhead lines. New transformers are also being installed.

Planning for overhauls of the 805 MW generators (G22, G23, G24) began in 2011. The overhauls started in 2013 with G22. G23 started in 2014, and G24 in 2016. They were planned to be finished in 2014, 2016, and 2017, respectively.

How the Dam Works and Its Benefits

The dam's main goal, irrigation, was put on hold during World War II. The dam's powerhouses started making electricity around the start of the war. This electricity was very important for the war effort. It powered aluminum factories and Boeing airplane factories. In 1943, its electricity was also used to make plutonium for the top-secret Manhattan Project.

Watering Farmland

Water is pumped from Lake Roosevelt up 280 ft (85 m) to a feeder canal. From there, the water goes to Banks Lake. Banks Lake can hold a lot of water. The plant's twelve pumps can move a huge amount of water to the lake. The Columbia Basin Project currently waters 670,000 acres (2,700 km2) of land. It has the potential to water even more. Over 60 different crops are grown in this area.

Generating Power

Grand Coulee Dam has four powerhouses with 33 hydroelectric generators. The original Left and Right Powerhouses have 18 main generators. They also have three service generators. Their total capacity is 2,280 MW.

The first generator started in 1941. All 18 were working by 1950. The Third Power Plant has six main generators. Their total capacity is 4,215 MW. Some of these generators can run at a higher maximum capacity. This brings the dam's total maximum capacity to 7,079 MW. The Pump-Generating Plant has six pump-generators. They have a capacity of 314 MW. When they pump water into Banks Lake, they use 600 MW of electricity.

Each generator gets water from its own large pipe, called a penstock. The biggest penstocks feed the Third Power Plant. They are 40 ft (12 m) wide. They can supply a lot of water. The dam's power facilities now have an installed capacity of 6,809 MW. In 2022, the dam made 21.17 TWh of electricity.

| Location | Type | Quantity | Capacity (MW) | Total capacity (MW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Powerhouse | Francis turbine, service generator | 3 (LS1-LS3) | 10 | 30 |

| Francis turbine, main generator | 9 (G1-G9) | 125 | 1,125 | |

| Right Powerhouse | Francis turbine, main generator | 9 (G10-G18) | 125 | 1,125 |

| Third Power Plant | Francis turbine, main generator | 3 (G22-G24) | 805 | 2,415 |

| Francis turbine, main generator | 3 (G19-G21) | 600 (Max: 690 MW) | 1,800 | |

| Pump-Generating Plant | Pump-generator, peak generator | 4 (PG9-PG12) | 53.5 | 214 |

| Pump-generator, peak generator | 2 (PG7-PG8) | 50 | 100 | |

| Totals | 33 | 6,809 |

The Spillway

Grand Coulee Dam's spillway is 1,650 feet (500 m) long. It has gates that control the water flow. Its maximum capacity is 1,000,000 cu ft/s (28,000 m3/s). A record flood in May and June 1948 showed the dam's limited flood control at the time. The flood damaged areas downstream. This led to the Columbia River Treaty. The treaty helped regulate the river's flow with dams in Canada.

Costs and Benefits

The Bureau of Reclamation thought the dam would cost $168 million in 1932. It actually cost $163 million in 1943. Finishing the power stations and fixing problems added another $107 million. This brought the total to $270 million by 1953. The Third Powerplant was estimated to cost $390 million in 1967. But it ended up costing $730 million by 1973.

Even with higher costs, the dam became a success. The Third Powerplant, for example, brought in twice as much money as it cost. The dam has irrigated about half the land predicted. But the value of crops has doubled over the years. The Bureau expects the money from power and irrigation will pay for the dam's construction by 2044.

Impact on Environment and People

The dam had a big impact on local Native American tribes. Their way of life depended on salmon. The dam has no fish ladder. This stops fish from migrating upstream. It blocked over 1,100 mi (1,770 km) of natural salmon spawning areas. This meant salmon could not reach the Upper Columbia Basin. The "June hogs," very large salmon, disappeared. The Spokane and other tribes could no longer hold their sacred salmon ceremonies.

Grand Coulee Dam flooded over 21,000 acres (85 km2) of important land. Native Americans had lived and hunted there for thousands of years. Settlements and burial grounds had to be moved. The Office of Indian Affairs worked with the Bureau of Reclamation. They helped move human remains to new Native American grave sites. This project started in September 1939. Many artifacts were found.

The town of Inchelium, Washington, home to about 250 Colville Indians, was submerged. It was later moved. Kettle Falls, a main Native American fishing spot, was also flooded. Over 600,000 salmon were caught there each year. This fishing was stopped. In June 1940, the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation held a "Ceremony of Tears." It marked the end of fishing at Kettle Falls. The falls were flooded within a year.

The dam has changed habitats for animals like mule deer and pygmy rabbits. This has caused their populations to decrease. But it has also created new wetlands. The dam changed the traditional way of life for native people. The government later paid the Colville Indians about $53 million in the 1990s. They also get about $15 million each year. In 2019, a bill passed to give more money to the Spokane Tribe.

To help with the lack of fish passage, three fisheries were created above the dam. They release fish into the upper Columbia River. Half of these fish are for the displaced tribes. A quarter of the reservoir is set aside for tribal hunting and boating.

Visiting the Dam

The Visitor Center was built in the late 1970s. It has historical photos, rock samples, and models of turbines and the dam. The building was designed by Marcel Breuer. It looks like a generator part. Since May 1989, a laser light show is projected onto the dam's wall on summer evenings. It shows images of battleships and the Statue of Liberty.

Tours of the Third Power Plant are open to the public. They last about an hour. Visitors take a shuttle to see the generators. They also travel across the main dam span.

The headquarters of the Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area is near the dam. The lake is a great place for fishing, swimming, canoeing, and boating.

Woody Guthrie's Connection

Folk singer Woody Guthrie wrote some of his most famous songs while working near the dam. In 1941, Guthrie moved to Oregon for a job. He was hired to narrate a documentary about the Grand Coulee Dam. He was also asked to sing songs for the film.

The Department of the Interior hired him for one month. He was to write songs about the Columbia River and the dams. Guthrie traveled around the Columbia River and the Pacific Northwest. He said it was "a paradise," which inspired him. In one month, Guthrie wrote 26 songs. These included "Roll On, Columbia, Roll On", "Pastures of Plenty", and "Grand Coulee Dam". The songs were later released as Columbia River Songs. Guthrie was paid $266.66 for his work in 1941.

The film Columbia River was finished in 1949. It featured Guthrie's music. The project had been delayed by World War II.

See also

In Spanish: Presa Grand Coulee para niños

In Spanish: Presa Grand Coulee para niños

- John L. Savage – Chief design engineer for the Bureau of Reclamation during construction.

- List of largest power stations in the world

- List of dams in the Columbia River watershed

- List of largest power stations in the United States

- List of largest hydroelectric power stations in the United States

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |