Columbia River Treaty facts for kids

The Columbia River Treaty is an important agreement made in 1961 between Canada and the United States. It's all about how they would work together to build and run dams on the upper Columbia River. The main goals were to create electricity and control floods in both countries.

Four dams were built because of this treaty: three in British Columbia, Canada (the Duncan Dam, Mica Dam, and Keenleyside Dam), and one in Montana, USA (the Libby Dam).

The treaty said that Canada would get half of the benefits from the electricity and flood control that the US received because of Canada's dams. While these dams have brought huge economic benefits to both British Columbia and the US Pacific Northwest, there have also been concerns. People worried about the effects on local communities and the environment.

Contents

Why the Treaty Was Made

In 1944, Canada and the US started looking into building dams together on the Columbia River. Things moved slowly until a big flood in 1948. This flood caused a lot of damage, even destroying a city called Vanport in Oregon.

This disaster made both countries more interested in flood protection and needing more electricity. So, they spent 11 years discussing and planning new dams in Canada. In 1959, they agreed on how to share the costs and benefits. The treaty was officially signed on January 17, 1961, by Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker and US President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The treaty didn't start right away. It took over three years to figure out how to pay for the Canadian dams and how Canada would sell the extra electricity it didn't need. In 1964, new agreements were signed, allowing Canada to sell its share of electricity to US power companies. Finally, the treaty officially began on September 16, 1964.

United States' Role

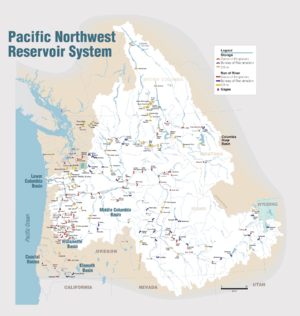

The United States began building dams on the lower Columbia River in the 1930s. These dams were for making electricity, controlling floods, helping boats navigate, and watering farms. This dam building started before the Columbia River Treaty was even in place.

During the Great Depression, the US government pushed for dam construction as a way to create jobs. Dams like Bonneville Dam and Grand Coulee Dam were started then. Even with these dams, the US realized they needed more storage capacity upstream to fully control floods and make the most electricity. They understood that working with Canada to build more storage dams would allow them to release water when needed, not just when the snow melted.

Canada's Role

In Canada, British Columbia's Premier W.A.C. Bennett was a big supporter of building new infrastructure in the 1950s and 1960s. He was the main Canadian force behind the Columbia River Treaty. Bennett believed in public power and had a "Two Rivers Policy." This plan was to develop hydroelectric power on both the Peace River and the Columbia River.

Bennett wanted to develop the Peace River for northern growth and the Columbia River for industries across the province. However, British Columbia didn't have enough money to develop both rivers at the same time. So, the Columbia River Treaty became a unique chance to get the necessary funds.

In 1961, a law was passed that led to the creation of BC Hydro in 1963. This new government-owned company could get loans at lower interest rates to build the dams. BC Hydro became responsible for the Canadian dams mentioned in the treaty and for managing the treaty's daily operations.

Bennett also arranged for the sale of Canada's share of the power (called the Canadian Entitlement). This sale brought in about C$274.8 million in 1964 for the first 30 years. This money allowed British Columbia to develop both the Columbia and Peace rivers at the same time, making Bennett's "Two Rivers Policy" a reality.

In short, British Columbia pursued the treaty because it offered a way to build hydroelectric projects that wouldn't have been possible otherwise. They hoped these projects would boost industry and grow the economy.

What the Treaty Said

The treaty required Canada to provide 19.12 cubic kilometers (15.5 million acre-feet) of usable water storage behind three large dams.

Quick facts for kids Duncan Dam |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Country | Canada |

| Location | Howser, British Columbia |

| Coordinates | 50°15′03″N 116°57′03″W / 50.25083°N 116.95083°W |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Impounds | Duncan River |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Duncan Lake |

| Total capacity | 1.70 km3 (1,380,000 acre⋅ft) |

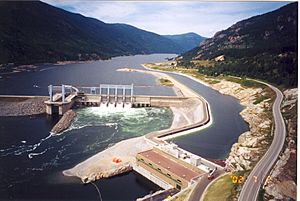

| Hugh Keenleyside Dam | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Country | Canada |

| Location | Castlegar, British Columbia |

| Coordinates | 49°20′22″N 117°46′19″W / 49.33944°N 117.77194°W |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Impounds | Columbia River |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Arrow Lakes |

| Total capacity | 8.76 km3 (7,100,000 acre⋅ft) |

| Mica Dam | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Country | Canada |

| Location | Mica Creek, British Columbia |

| Coordinates | 52°04′40″N 118°33′59″W / 52.07778°N 118.56639°W |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Impounds | Columbia River |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Kinbasket Lake |

| Total capacity | 15 km3 (12,000,000 acre⋅ft) |

| Libby Dam | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Country | United States |

| Location | Libby, Montana |

| Coordinates | 48°24′37″N 115°18′54″W / 48.41028°N 115.31500°W |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Impounds | Kootenai River |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Lake Koocanusa |

| Total capacity | 7.43 km3 (6,020,000 acre⋅ft) |

The Duncan Dam (1967) provided 1.73 cubic kilometers (1.4 Maf). The Arrow Dam (1968), later renamed the Keenleyside Dam, provided 8.76 cubic kilometers (7.1 Maf). The Mica Dam (1973) provided 8.63 cubic kilometers (7.0 Maf) for the treaty, but was built even larger. These Canadian dams help with flood protection and make more electricity in both Canada and the US.

The treaty also allowed the US to build the Libby Dam on the Kootenay River in Montana. This dam created the Koocanusa reservoir, which extends 42 miles (68 km) into Canada. The name "Koocanusa" comes from "Kootenai," "Canada," and "USA." The Libby Dam started operating in 1972 and helps with power and flood control in both countries. Canada did not pay the US for the benefits from Libby Dam, and the US did not pay Canada for the land flooded by its reservoir.

Most Canadian treaty dams were first built only to control water flow. However, a power plant was added to the Keenleyside Dam in 2002. The Duncan Dam still only stores water and doesn't generate power.

BC Hydro is the Canadian organization that manages the treaty. In the US, the Bonneville Power Administration and the US Army Corps of Engineers manage it. A special board with members from both countries checks on the treaty every year.

Payments for US Benefits

For the benefits the US gets from Canada's water storage, the treaty required the US to:

- Give Canada half of the extra electricity generated in the US (called the Canadian Entitlement). This amount changes each year.

- Make a one-time payment for half the value of future flood damages prevented in the US.

The Canadian Entitlement is usually around 4,400 GWh (gigawatt-hours) of electricity per year. This electricity is sold by Powerex, a Canadian company.

The US paid a total of $64.4 million (C$69.6 million) for the flood control benefits. This payment covered flood protection until September 2024. After 2024, if the US needs Canada to store water for flood control, they will have to pay Canada for the operating costs and any money Canada loses.

Ending the Treaty

The treaty doesn't have a set end date. However, either country can choose to end most parts of it after 60 years (which is September 16, 2024). They just need to give 10 years' notice. If the treaty ends, some parts will continue, like the US being able to ask for flood control storage and the operation of Libby Dam.

Both the Canadian and US governments are reviewing the treaty before 2024. They are considering three main options:

- Keep the treaty as it is, with the change to "called upon" flood control.

- End the treaty (but still keep the "called upon" flood control).

- Negotiate new changes to the treaty, possibly adding environmental goals.

Impacts of the Treaty

At first, there was some disagreement about the treaty in British Columbia. The province had to build three big dams but wasn't sure who would buy the extra electricity. This was solved in 1964 when a group of US power companies agreed to buy Canada's share of electricity for 30 years for C$274.8 million. British Columbia used this money, along with the C$69.6 million from the US for flood control, to build the Canadian dams.

Over the years, people noticed that the treaty mainly focused on electricity and flood control. It didn't directly address other important issues like protecting fish, irrigation, or other environmental concerns. However, the treaty does allow for changes to be made to include these interests. For over 20 years, operations have been adjusted to be more "fish-friendly" on both sides of the border.

Premier W.A.C. Bennett was a tough negotiator for Canada. The US paid C$275 million, which grew to C$458 million with interest. Some people, like Bennett's successor Dave Barrett, felt the dams and power lines ended up costing much more. However, Dr. Hugh L. Keenleyside, for whom the Keenleyside Dam is named, explained that the actual costs were reasonable for the time. He noted that the value of the US payments had grown to C$479 million by 1973.

Since 2003, when the 30-year sale of the Canadian Entitlement ended, Canada has been receiving the actual electricity from the US. This has been a huge benefit, bringing in about C$202 million per year in revenue for British Columbia.

Social Impacts

Local Communities

The construction of the Columbia River Treaty dams had a big impact on local residents. BC Hydro had to buy land and homes and relocate people. For example, in the Arrow Lakes area, 3,144 properties were bought, and 1,350 people had to move. The Duncan Dam caused 39 properties to be bought and 30 people to move. At Mica Dam, 25 properties were bought.

The Arrow Lake area saw the most changes and disagreements. Some people who worked on the dam felt proud. But many residents felt powerless because there were no local meetings about the treaty, and their area was going to be flooded.

To help with the long-term social and economic effects of this flooding, the Columbia Basin Trust was created.

While BC Hydro paid for houses, it didn't fully account for the loss of a self-sufficient lifestyle. Many people lived off the land through farming, livestock, and fishing, with low taxes. Moving to a city meant losing this way of life. Some residents felt the payments were unfair but accepted them because they felt they couldn't fight it in court.

BC Hydro did build new communities for those who were relocated, with electricity, water, phone services, schools, churches, parks, and stores. The dams also created jobs and brought electricity to remote areas that didn't have it before.

However, the emotional loss of homes and familiar landscapes was hard to compensate for. This was especially true for First Nations people. The Sinixt people, who had lived in the Columbia River Valley for thousands of years, lost sacred burial grounds. This was very upsetting for their community. The Canadian government had even declared the Sinixt officially extinct in 1953, even though many Sinixt people were still alive. This timing, just before the treaty, raised questions.

Provincial Impacts

The goal of the treaty was for Canada and the US to achieve more together than they could alone. Some people felt this didn't happen, while others disagreed.

British Columbia has seen both good and bad impacts. Positive impacts include better flood protection, more electricity generation, and the Canadian Entitlement power (worth about $300 million annually). Early on, BC received large payments from the US for selling its power share and for flood protection. The treaty also created many jobs in dam construction and operation. It led to lower electricity rates for customers. Many later power projects in BC were also made possible because the treaty helped regulate water flow.

However, the treaty also had negative impacts. The cost for BC to build the three dams was more than the money it initially received from the US. The province also had to pay for new highways, bridges, railway relocation, and support for affected people. Some believe this led to less money for schools and hospitals.

It's now clear that the value of the Canadian Entitlement was underestimated when the treaty was signed. While Bennett's government was criticized for this, it was hard to predict the future value accurately. The treaty also led to the flooding of about 600 square kilometers (230 square miles) of fertile valley bottoms, including the Arrow Lakes, Duncan, Kinbasket, and Lake Koocanusa reservoirs. No one ever calculated the value of the flooded forest land, which could have produced valuable timber.

Environmental Impacts

Canada

Before dams, the Columbia River's water levels changed predictably with the seasons. After dams were built, these changes became much bigger. High spring and summer flows were reduced, and fall and winter flows increased to meet US power needs. This meant that during high water, farmland was covered, and when water levels dropped, fertile soil was washed away.

The creation of reservoirs also flooded the habitats of many animals, including an estimated 8,000 deer, 600 elk, 1,500 moose, 2,000 black bears, and 70,000 ducks and geese.

Dams affect everything upstream and downstream. Upstream, rising water covers nesting grounds and migration routes for birds. Changing water levels in reservoirs make it hard for aquatic life to find food. Nutrients that used to flow downstream get trapped in reservoirs, changing water quality and temperature. For example, a 9-degree Celsius difference was once measured between the Columbia and Snake rivers. Silt settling on the bottom covers rocks, ruining fish spawning grounds and hiding places. Changes in water quality, like acidity, can also be deadly to aquatic life.

Salmon and Steelhead trout travel from the ocean upriver to lay their eggs. Dams make this journey very difficult. Many dams on the Columbia River now have fish ladders to help fish swim upstream.

Swimming downstream is also a problem for young fish. Before dams, currents easily carried young fish to the ocean. Now, the slower water in reservoirs makes them use more energy. Many fish also die in dam turbines. While older estimates suggested 8-12% loss per dam, efforts to make turbines safer have greatly reduced this. If a fish hatches far upstream, it might have to pass through many dams, leading to significant losses. While fish hatcheries help some species, improving migration is key to increasing fish populations. It's a combination of dams, slow water, habitat loss, pollution, and overfishing that harms fish populations.

From 1965 to 1969, over 27,000 acres (11,000 hectares) of trees were cut down along the Columbia River to clear land for the new flood plain. This made the soil unstable, leading to sandstorms and vast mud flats in wet periods.

The BC Fish and Wildlife Branch started studying the dams' impact on animals in the late 1940s. Their work, with local conservation groups, focused on protecting Kokanee salmon, which were threatened by the Duncan Dam. Since other fish like Rainbow and Bull Trout eat Kokanee, keeping their numbers strong was important. As a result, BC Hydro funded the construction of the Meadow Creek Spawning Channel in 1967. This 3.3 km (2 miles) channel is the longest human-made spawning ground for freshwater sport fish. It supports 250,000 spawning Kokanee each year. BC Hydro also helps the Creston Valley Wildlife Management Area and the Columbia Basin Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program.

United States

The US part of the Columbia River already had many dams before the treaty. Since the US mainly needed more power generation, and they already had the capacity, they weren't required to build new dams under the treaty. The main direct environmental impact in the US was from the Libby Dam in Montana. Its reservoir, Lake Koocanusa, extends into Canada.

Building the Libby Dam was slow because it involved a reservoir crossing the border. By 1966, when construction began, environmental concerns were growing. Studies showed the dam would harm large animals like big-horned sheep and elk. While Libby Dam could help with irrigation downstream, scientists found it would also destroy wetlands and change the river's flow.

Because of pressure from environmental groups, the US Army Corps of Engineers created a plan to reduce the damage. This plan included building fish hatcheries, buying land for animals whose habitats were flooded, and adding technology to control the temperature of water released from the dam.

The Libby Dam flooded 40,000 acres (about 162 square kilometers), changing ecosystems both upstream and downstream. This was the biggest direct environmental effect of the treaty in the US. The increased water storage from the Canadian dams gave river managers much more control over the river's flow. They could now reduce peak flows and increase low flows, releasing water to meet high power demands in winter and summer. This was a big change from the river's natural flow, which was driven by snowmelt in the summer.

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |