Statue of Liberty facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Location | Liberty Island New York City |

| Height |

|

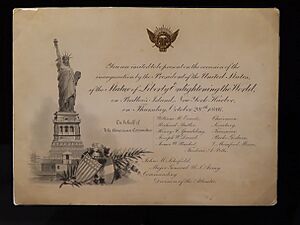

| Dedicated | October 28, 1886 |

| Restored | 1938, 1984–1986, 2011–2012 |

| Sculptor | Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi |

| Visitors | 4.5 million (in 2019) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, vi |

| Designated | 1984 (8th session) |

| Reference no. | 307 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Designated | October 15, 1924 |

| Designated by | President Calvin Coolidge |

| Official name: The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World | |

| Designated | September 14, 2017 |

| Reference no. | 100000829 |

| Official name: Statue of Liberty National Monument, Ellis Island and Liberty Island | |

| Designated | May 27, 1971 |

| Reference no. | 1535 |

|

Invalid designation

|

|

| Designated | June 23, 1980 |

| Reference no. | 06101.003324 |

The Statue of Liberty, also known as Liberty Enlightening the World, is a giant statue on Liberty Island in New York Harbor. It was a special gift to the United States from the people of France. French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi designed the statue. Its metal frame was built by Gustave Eiffel, who also designed the Eiffel Tower. The statue was officially opened on October 28, 1886.

The statue shows a woman dressed in flowing robes, like an ancient Roman goddess of freedom. She holds a torch high with her right hand. In her left hand, she carries a tablet with the date July 4, 1776, written in Roman numerals. This is the date the U.S. Declaration of Independence was signed. Her left foot steps on a broken chain, which reminds us of the end of slavery in the United States. After it was built, the statue became a famous symbol of freedom and a welcoming sight for immigrants arriving by sea.

The idea for the statue started in 1865. A French historian named Édouard de Laboulaye suggested a monument to celebrate 100 years of U.S. independence. He also wanted to honor American democracy and the freedom of slaves. A war in France delayed the project. In 1875, Laboulaye proposed that France would pay for the statue. The United States would provide the land and build the base, called a pedestal. Bartholdi finished the head and the arm holding the torch first. These parts were shown at big events to get people excited.

The torch-bearing arm was displayed in Philadelphia in 1876. It was also in Madison Square Park in Manhattan from 1876 to 1882. Raising money was hard, especially for the Americans. By 1885, work on the pedestal almost stopped because of a lack of funds. A newspaper publisher, Joseph Pulitzer, asked people to donate. More than 120,000 people gave money, most of them less than a dollar. The statue was built in France, then shipped in pieces to New York. It was put together on what was then called Bedloe's Island. The statue's completion was celebrated with New York's first ticker-tape parade. President Grover Cleveland led the dedication ceremony.

The statue was first managed by the U.S. Lighthouse Board. Later, the War Department took over. Since 1933, the National Park Service has cared for it. It is now part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument and a popular tourist spot. Visitors can go inside the pedestal and up to the crown. However, the torch has been closed to the public since 1916.

Contents

How the Statue Was Created

The Idea for Lady Liberty

The idea for the Statue of Liberty came from Édouard René de Laboulaye. He was a French historian and a strong supporter of ending slavery. In 1865, he talked with sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi about a gift from France to the United States. Laboulaye wanted to celebrate America's independence and the end of slavery. He thought it would be great if both countries worked together on a monument.

Bartholdi was inspired by this idea. He had also thought about building a huge lighthouse in Egypt. It would have been a giant female figure holding a torch. This earlier idea was similar to the ancient Colossus of Rhodes, a huge statue that stood at a harbor entrance. However, the Egyptian project was too expensive and was never built.

Bartholdi learned about a large copper statue in Italy called Sancarlone. It was made of copper sheets over an iron frame. He chose copper for his statue because it was cheaper, lighter, and easier to move than bronze or stone.

A war between France and Prussia delayed the project. After the war, France became a more liberal republic. Bartholdi and Laboulaye decided it was the right time to talk to important Americans. In 1871, Bartholdi traveled to the United States.

When he arrived in New York Harbor, Bartholdi saw Bedloe's Island. He thought it was the perfect spot for the statue. Ships entering New York would sail right past it. He was happy to learn the U.S. government owned the island. President Ulysses S. Grant told him it would be easy to get the site.

Designing Lady Liberty

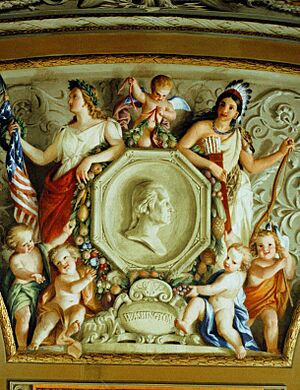

Bartholdi and Laboulaye wanted the statue to represent American freedom. They looked at symbols used in early American history. One symbol was Columbia, a female figure representing the United States. Another was Liberty, based on Libertas, the Roman goddess of freedom. This goddess was especially important to freed slaves in ancient Rome. A Liberty figure was on many American coins and in art, like the Statue of Freedom on top of the United States Capitol Building.

Bartholdi's design was inspired by ancient art. It included ideas from the Egyptian goddess Isis and the Roman goddess Columbia. He wanted a peaceful image, not a revolutionary one. So, his figure is fully dressed and holds a torch, which stands for progress.

Bartholdi's early designs all showed a female figure in a classical style. She would represent liberty, wear a gown and cloak, and hold a torch. Many people believe the face was modeled after Bartholdi's mother. However, experts say there is no proof of this. He designed the face to be serious and strong. This would make the statue look impressive in the harbor.

Bartholdi changed the design as he worked. He first thought about having Liberty hold a broken chain. But he decided this might cause too much disagreement after the Civil War. The finished statue does step over a broken chain, but it is hard to see. Her right foot is raised, giving her a dynamic look. This shows a mix of standing still and moving forward.

For Liberty's left hand, Bartholdi chose a tablet. On it, he wrote "JULY IV MDCCLXXVI," the date of the United States Declaration of Independence. This connected the idea of liberty with America's birth.

Building the Statue in France

Bartholdi asked his friend, architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, for help. Viollet-le-Duc suggested building a brick support inside the statue. He also chose copper sheets for the skin. The copper would be shaped using a method called repoussé. This meant heating the sheets and hammering them with wooden tools. This method made the statue light for its size. The copper skin would be only about 2.4 millimeters (0.094 inches) thick.

The project was delayed when Viollet-le-Duc became ill and passed away in 1879. Then, Gustave Eiffel took over as chief engineer. Eiffel decided to use an iron truss tower instead of a brick pier. He designed a flexible structure. This allowed the statue to sway slightly in the wind and expand in the heat. This prevented the copper skin from cracking. Eiffel used flat iron bars and springs to connect the copper skin to the inner frame. This way, the skin could move a little without damage. To stop the copper and iron from reacting, Eiffel used asbestos soaked in shellac as insulation.

Eiffel's design was an early example of "curtain wall" construction. This is where the outside of a building is supported by an inner frame, not by itself. He also added two spiral staircases inside. These would help visitors reach the crown. The parts of the iron tower were built in Eiffel's factory near Paris.

Bartholdi decided to build the entire statue in France. Then, it would be taken apart, shipped to the U.S., and put back together. In a special moment, the first rivet was placed by Levi P. Morton, the U.S. Ambassador to France. By 1882, the statue was built up to the waist. Laboulaye passed away in 1883. The completed statue was officially given to Ambassador Morton in Paris on July 4, 1884. The French government agreed to pay for its journey to New York. By January 1885, the statue was taken apart and packed into crates for its trip across the ocean.

Building the Pedestal in America

Raising money for the pedestal in the U.S. was very difficult. A tough economic time in the 1870s made it harder. Some people criticized the statue, saying Americans should design their own public works. The New York Times even said, "no true patriot can countenance any such expenditures for bronze females." Because of these problems, the American committees did little for several years.

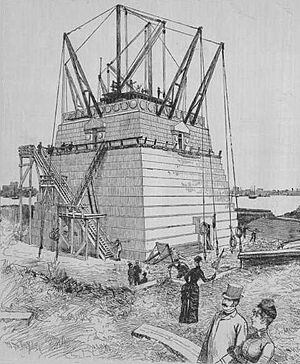

The statue's foundation was built inside Fort Wood. This was an old army base on Bedloe's Island. The fort had eleven-pointed walls. The statue and its pedestal were set to face southeast. This way, it would greet ships coming into the harbor.

In 1881, Richard Morris Hunt was chosen to design the pedestal. He planned a 114-foot-tall pedestal. But because of money problems, it was made shorter, at 89 feet. Hunt's design included classical elements and some inspired by Aztec architecture. It was a pyramid shape, 62 feet square at the bottom and 39.4 feet at the top. The pedestal was made of thick concrete walls, covered with granite blocks. This was the largest amount of concrete poured at that time.

Joachim Goschen Giæver, a Norwegian civil engineer, designed the structural framework for the pedestal. He worked from Gustave Eiffel's drawings.

Raising Money for the Pedestal

Fundraising for the pedestal began in 1882. The committee held many events. For one event, poet Emma Lazarus was asked to write something. She first said no, thinking she couldn't write about a statue. But she was helping refugees who had fled unfair treatment in Europe. She saw a way to connect their struggles to the statue. Her poem, "The New Colossus", includes the famous lines: "Give me your tired, your poor/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free." This poem is now strongly linked to the Statue of Liberty. It is written on a plaque in the statue's museum.

Even with these efforts, money was still short. New York's governor, Grover Cleveland, stopped a bill to give $50,000 for the statue. An attempt to get $100,000 from Congress also failed. The New York committee stopped work on the pedestal. Other cities offered to pay if the statue was moved to them.

Joseph Pulitzer, who owned the New York World newspaper, started a campaign to raise $100,000. Pulitzer promised to print the name of every person who donated, no matter how small the amount. This idea excited New Yorkers. People sent in small amounts, like "60 cents, the result of self denial" from a young girl. A group of children sent a dollar they saved for the circus. Donations poured in, and work on the pedestal started again. France raised about $250,000 for the statue. The U.S. had to raise about $300,000 for the pedestal.

Putting It All Together

On June 17, 1885, the French ship Isère arrived in New York. It carried the crates holding the statue's pieces. Two hundred thousand people lined the docks to welcome the ship. On August 11, 1885, the World announced that $102,000 had been raised. Most of this came from small donations.

The pedestal was finished in April 1886. Then, workers began putting the statue back together. Eiffel's iron framework was anchored to steel beams inside the concrete pedestal. Workers carefully attached the copper skin sections. They had to hang from ropes because the pedestal was too wide for scaffolding. Bartholdi wanted to put floodlights on the torch's balcony. But the Army Corps of Engineers said no, fearing it would blind ship pilots. Instead, Bartholdi cut holes in the torch, which was covered in gold leaf, and put lights inside. A power plant was built on the island to light the torch.

When built, the statue was a shiny reddish-brown. But within 20 years, it turned green. This green color, called patina, formed as the copper reacted with air and water. This patina actually protects the copper from further damage.

The Big Day: Dedication

The dedication ceremony was held on October 28, 1886. President Grover Cleveland led the event. That morning, a huge parade took place in New York City. Hundreds of thousands of people watched. President Cleveland led the procession. The parade route went past the World newspaper building. As it passed the New York Stock Exchange, traders threw ticker tape from windows. This started the tradition of ticker-tape parades.

A boat parade began at 12:45 p.m. President Cleveland took a yacht to Bedloe's Island for the ceremony. Ferdinand de Lesseps spoke first for the French committee. Then, Senator William M. Evarts spoke for the New York committee. A French flag covered the statue's face. It was supposed to be lowered at the end of Evarts's speech. But Bartholdi thought a pause was the end and lowered the flag too early. The crowd cheered, ending Evarts's speech. President Cleveland then spoke, saying the statue's light would "pierce the darkness of ignorance and man's oppression." Bartholdi was asked to speak but declined.

Only important guests were allowed on the island for the ceremony. Women were mostly kept off, except for Bartholdi's wife and Lesseps's granddaughter. Officials said they feared women might get hurt in the crowd. This upset women's rights activists. They hired a boat and got as close as they could. Their leaders gave speeches, praising Liberty as a woman and asking for women's right to vote. A fireworks show was planned but moved to November 1 due to bad weather.

After the dedication, an African American newspaper, The Cleveland Gazette, made a strong point. It suggested the torch should not be lit until America was truly free for everyone. It highlighted that many people still faced unfair treatment.

After the Dedication

Early Years and Changes (1886–1933)

When the torch was first lit, it gave off a very faint light. It was hard to see from Manhattan. The U.S. Lighthouse Board took over the statue in 1887. They tried to make the torch brighter, but it remained almost invisible at night. Bartholdi suggested gilding the statue to make it reflect more light, but this was too costly. In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt transferred the statue to the War Department. It was not useful as a lighthouse.

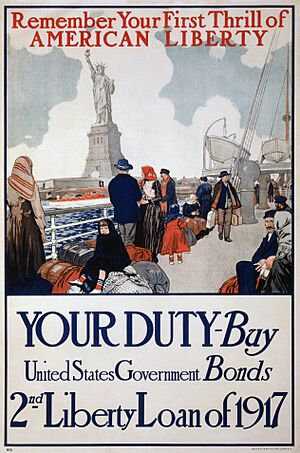

Many immigrants came to the U.S. in the late 1800s and early 1900s. They often entered through New York. They saw the statue as a symbol of welcome to their new home. This idea grew stronger when an immigrant processing station opened on nearby Ellis Island. This view matched Emma Lazarus's poem, which called the statue "Mother of Exiles." In 1903, her poem was engraved on a plaque at the statue's base.

Immigrants often shared how excited they felt seeing the Statue of Liberty. One person from Greece remembered saying, "Lady, you're such a beautiful! You opened your arms and you get all the foreigners here. Give me a chance to prove that I am worth it."

The statue quickly became a famous landmark. It was originally a dull copper color. But by 1906, it had completely turned green due to the copper oxidizing. Some thought this green color meant the statue was rusting. Congress approved money for repairs and to paint the statue. But many people protested painting the outside. The Army Corps of Engineers found that the green patina actually protected the copper. So, only the inside was painted. An elevator was also installed to take visitors to the top of the pedestal.

On July 30, 1916, during World War I, saboteurs caused a huge explosion. It happened on the Black Tom peninsula in Jersey City, near Bedloe's Island. The explosion damaged the statue slightly, mostly its torch-bearing arm. The statue was closed for ten days. Repairs cost about $100,000. The narrow path up to the torch was closed for safety reasons and has stayed closed ever since.

Later that year, Ralph Pulitzer started a campaign to raise money for a new lighting system. He wanted to light the statue at night. President Woodrow Wilson turned on the new lights on December 2, 1916.

In 1924, President Calvin Coolidge made the statue a national monument.

National Park Service Takes Over (1933–1982)

In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt moved the statue to the National Park Service (NPS). By 1937, the NPS managed all of Bedloe's Island. The island was turned into a park. Old buildings were removed, and new granite steps were built for visitors. The NPS also repaired the statue's inside. Rusted iron steps were replaced with concrete ones. Copper was added to stop rainwater from leaking into the pedestal. The statue was closed from May to December 1938 for this work.

During World War II, the statue stayed open. But it was not lit at night due to wartime blackouts. It was briefly lit on December 31, 1943, and on D-Day, June 6, 1944. On D-Day, its lights flashed "dot-dot-dot-dash," which is Morse code for V, meaning victory. New, powerful lights were installed in 1944–1945. After the war, the statue was lit every night. In 1946, the inside of the statue was coated with a special plastic. This made it easy to clean off graffiti.

In 1956, Bedloe's Island was officially renamed Liberty Island. This was a change Bartholdi had wanted long ago. Nearby Ellis Island became part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument in 1965. In 1972, an immigration museum opened in the statue's base. It closed in 1991 when a new museum opened on Ellis Island.

The statue was sometimes used for protests. In 1970, Ivy Bottini and others from the National Organization for Women hung a banner that said "WOMEN OF THE WORLD UNITE!" In 1971, veterans protested at the statue. Other groups also used the statue to bring attention to their causes.

A strong new lighting system was installed for America's 200th birthday in 1976. The statue was the center of "Operation Sail," a parade of tall ships from around the world. The day ended with amazing fireworks near the statue.

Big Renovation and Reopening (1982–2000)

Engineers studied the statue closely for its 100th birthday in 1986. In 1982, they announced that the statue needed a lot of repair. The right arm was not attached correctly and swayed too much in strong winds. This was a risk to its structure. Also, the head was two feet off-center. One of the crown's rays was rubbing a hole in the arm when the statue moved. The inner metal frame was badly rusted. About two percent of the outside copper plates needed replacing.

In May 1982, President Ronald Reagan started a commission to raise money for the repairs. This group raised over $350 million for both the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. A special campaign with American Express helped. For every purchase made with their card, the company gave one cent to the statue's renovation. This raised $1.7 million.

In 1984, the statue closed for renovations. Workers built the world's largest free-standing scaffold around it. Layers of paint were removed from the inside of the copper skin. A special baking soda blast removed old tar without harming the copper. Workers had to wear special suits because of asbestos used inside. Larger holes in the copper skin were fixed, and new copper was added. The new copper came from a rooftop at Bell Labs that had a similar green color.

The torch had been leaking water since 1916. It was replaced with an exact copy of Bartholdi's original design. The new torch's flame is covered in 24-karat gold. It reflects the sun during the day and is lit by floodlights at night.

The entire iron frame designed by Gustave Eiffel was replaced. New stainless steel bars were used. These bars bend slightly and return to shape as the statue moves. This helps prevent damage. The lighting was also updated. New lights send beams to specific parts of the statue, showing off its details. The entrance to the pedestal was improved with new bronze doors. A modern elevator was installed for visitors. An emergency elevator was also added inside the statue.

From July 3–6, 1986, "Liberty Weekend" celebrated the statue's 100th birthday and its reopening. President Reagan and French President François Mitterrand were there. On July 4, there was another "Operation Sail" with tall ships. The statue reopened to the public on July 5. President Reagan said, "We are the keepers of the flame of liberty; we hold it high for the world to see."

Closures and Reopenings (2001–Present)

After the September 11 attacks in 2001, the statue and Liberty Island were closed. The island reopened at the end of 2001. The pedestal and statue remained closed. The pedestal reopened in August 2004. But the National Park Service said it was not safe for visitors to go inside the statue. This was due to the difficulty of getting people out in an emergency.

On May 17, 2009, the Secretary of the Interior announced the statue would reopen to the public on July 4. However, only a limited number of people could go up to the crown each day.

The statue, pedestal, and base closed again on October 29, 2011. This was for new elevators, staircases, and other facility upgrades. It reopened on October 28, 2012. But it closed again the next day because of Hurricane Sandy. The storm did not harm the statue itself. However, it damaged the ferry docks and other buildings on Liberty and Ellis Islands. The island reopened on July 4, 2013. Ellis Island reopened later that year.

The Statue of Liberty has also closed due to government shutdowns and protests. It closed during the October 2013 government shutdown. On July 4, 2018, it closed briefly when a woman protested immigration rules by climbing on the statue. It also closed on March 16, 2020, because of the COVID-19 pandemic. It partially reopened on July 20, 2020, but the crown did not reopen until October 2022.

A new Statue of Liberty Museum opened on Liberty Island on May 16, 2019. This $70 million museum is open to all visitors to the island. The old museum in the pedestal could only be accessed by a small number of visitors.

Visiting the Statue

Location and How to Get There

The Statue of Liberty is on Liberty Island in Upper New York Bay. It is south of Ellis Island. Both islands are part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument. While the islands are in New York territory, they are on the New Jersey side of the state line. Liberty Island is part of the borough of Manhattan in New York City.

There is no charge to enter the national monument. However, visitors must buy a ticket for the ferry service. Private boats are not allowed to dock at the island. Ferries leave from Liberty State Park in Jersey City and the Battery in Lower Manhattan. They also stop at Ellis Island, so you can visit both. All ferry riders go through airport-like security before boarding.

If you want to go inside the statue's base and pedestal, you need a special ticket. To climb the stairs inside the statue to the crown, you must buy a special ticket in advance. These tickets can be reserved up to five months ahead. About 425 people can visit the crown each day.

Climbers can only bring medicine, plastic water bottles, phones, and cameras. Lockers are available for other items. There is a second security check. The balcony around the torch has been closed since the 1916 explosion. But you can see the torch live through a webcam.

Plaques and Special Markers

There are several plaques and dedication tablets on or near the Statue of Liberty.

- A plaque on the copper skin says it is a huge statue of Liberty. It was designed by Bartholdi and built by a French company.

- Another tablet says the statue is a gift from France. It honors the friendship between the two nations.

- A tablet from the American Committee thanks those who raised money for the pedestal.

- The cornerstone has a plaque placed by the Freemasons.

- In 1903, a bronze tablet with Emma Lazarus's poem, "The New Colossus", was added. It was first inside the pedestal. Now, it is in the Statue of Liberty Museum.

- A second tablet, added in 1977, celebrates Emma Lazarus's life.

At the western end of the island, there are statues honoring people important to the Statue of Liberty. These include Americans Joseph Pulitzer and Emma Lazarus. Also honored are Frenchmen Bartholdi, Eiffel, and Laboulaye. These statues were made by sculptor Phillip Ratner.

Important Recognitions

President Calvin Coolidge made the Statue of Liberty a national monument in 1924. Ellis Island was added to the monument in 1965. In 1966, both were added to the National Register of Historic Places. The statue was added individually in 2017. It is also recognized by New Jersey and New York City as a historic place.

In 1984, the Statue of Liberty became a UNESCO World Heritage Site. UNESCO called the statue a "masterpiece of the human spirit." It said the statue is a powerful symbol of liberty, peace, human rights, and democracy.

Statue Measurements

| Part of Statue | Imperial Measurement | Metric Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Height of copper statue | 151 ft 1 in | 46 m |

| Ground to tip of torch | 305 ft 1 in | 93 m |

| Heel to top of head | 111 ft 1 in | 34 m |

| Height of hand | 16 ft 5 in | 5 m |

| Index finger | 8 ft 1 in | 2.44 m |

| Head from chin to cranium | 17 ft 3 in | 5.26 m |

| Length of nose | 4 ft 6 in | 1.48 m |

| Right arm length | 42 ft 0 in | 12.8 m |

| Tablet, length | 23 ft 7 in | 7.19 m |

| Height of pedestal | 89 ft 0 in | 27.13 m |

| Weight of copper used | 60,000 pounds | 27.22 tonnes |

| Weight of steel used | 250,000 pounds | 113.4 tonnes |

| Total weight of statue | 450,000 pounds | 204.1 tonnes |

| Thickness of copper skin | 3/32 of an inch | 2.4 mm |

Lady Liberty in Culture

Many smaller copies of the Statue of Liberty are found around the world. A smaller version, one-fourth the size, was given to Paris by Americans living there. It now stands on the Île aux Cygnes, facing its larger sister in New York. The Boy Scouts of America also donated about 200 copper replicas to states and cities across the U.S.

The statue is a popular symbol in American culture. It has appeared on coins and stamps. It was on special coins for its 1986 centennial. It was also on New York's state quarter in 2001. An image of the statue's torch is on the current ten-dollar bill.

Many groups use the statue's image. The Women's National Basketball Association's New York Liberty team uses its name and image in their logo. The New York Rangers hockey team has used the statue's head on a jersey. The Libertarian Party of the United States uses the statue in its emblem.

The Statue of Liberty is often seen in movies and books. In the 1968 movie Planet of the Apes, it is shown half-buried in sand. It is knocked over in the science-fiction film Independence Day. In Cloverfield, its head is ripped off. The statue has become a strong symbol in science fiction, often showing a future where things have changed.

-

The back side of a Presidential Dollar coin.

See also

In Spanish: Estatua de la Libertad para niños

In Spanish: Estatua de la Libertad para niños

- Goddess of Liberty, a statue on the Texas State Capitol dome.

- List of tallest statues

- Miss Freedom, a statue on the Georgia State Capitol dome.

- Place des États-Unis, a square in Paris, France.

- The Statue of Liberty (film), a 1985 documentary.

- Statues and sculptures in New York City

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |