Plains Indian warfare facts for kids

During the 1800s, Native American warriors on the Great Plains fought to protect their lands. They were sometimes called Braves by settlers. These brave warriors resisted the Westward expansion of the United States. Many different tribes lived on the Great Plains, but they often shared similar ways of fighting.

Contents

A History of Plains Warriors

When Spanish explorers first arrived in the 1500s, they didn't see the Plains Native Americans as especially warlike. For example, the Wichita in Kansas and Oklahoma lived in open villages without defenses. The Spanish even had friendly meetings with the Apache.

However, three main things changed this, making warfare more important:

- First, when Spain settled New Mexico, it led to more raids for goods and slaves between Spaniards and Native Americans.

- Second, French fur traders arrived, causing tribes to compete more for control over trade routes.

- Third, Native Americans got horses. This made them much more mobile and changed how they lived and fought.

From the 1600s to the late 1800s, fighting became a way of life and even a sport. Young men gained respect and valuable items by being warriors. This focus on individual bravery meant that winning personal fights and taking war trophies were highly valued.

Fighting Tactics

Plains Native Americans often raided other tribes, Spanish settlements, and later, American settlers. They sought horses and other goods. They mainly got guns and European items through trading. Their main trade goods were buffalo hides and beaver furs.

One of the most famous victories for Plains Native Americans against the United States was the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876. In this battle, the Lakota (Sioux) and Cheyenne tribes successfully defended their land.

While they fought hard to defend themselves, Plains warriors usually attacked to gain goods and personal honor. The highest honor was "counting coup"—touching a living enemy without harming them. Battles between Native American tribes often showed off bravery rather than trying to completely defeat the enemy. They preferred surprise attacks and quick raids instead of long, close combat. Success was often measured by how many horses or items were taken.

Casualties were usually low. Native Americans thought it was foolish to attack if it meant many of their own would be killed. Because their groups were small, losing even a few men could be a disaster. For example, at the battles of Adobe Walls in 1874 and Rosebud in 1876, Native Americans stopped fighting even when they were winning. They did this because the losses were not worth the victory. Decisions to fight were based on how much they might gain versus what they might lose. Losing one or two warriors was acceptable if they could get a large herd of horses. Generally, Plains Indians tried to avoid losing men in battle and would avoid fighting if it meant heavy losses.

Logistics and Mobility

Plains Native Americans were very mobile, tough, and skilled horse riders. They also knew the vast plains very well. These skills often helped them win battles against the U.S. army during the Westward expansion (from 1803 to about 1890).

However, even though they won many battles, Native American armies could not fight for very long periods. Warriors also needed to hunt for food for their families. The only exception was raids into Mexico by the Comanche and their allies. These raiders sometimes lived for months off the wealth of Mexican ranches and towns.

Amazing Horsemanship

Native Americans of the Great Plains learned to ride horses from a very young age. They rode small cayuse horses, which were first brought by Spanish explorers. They usually rode without saddles, using only a blanket for comfort.

During a fight, a warrior might hang off the side of his galloping horse. This used the horse as a shield while he fired his gun or shot arrows. The Comanche were known as some of the best horse warriors. The Economist newspaper noted in 2010 that they could shoot many arrows while hanging off a galloping horse. This skill amazed and scared both white and other Native American enemies. The American historian S. C. Gwynne called the Comanche "the greatest light cavalry on the earth" in the 1800s. Their raids in Texas terrified American settlers.

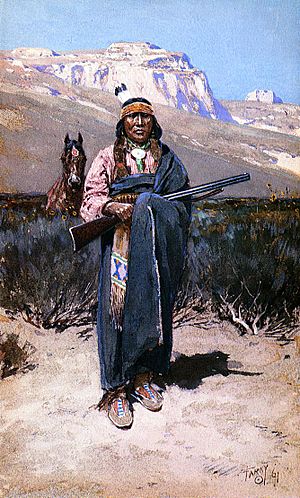

Warrior Insignia and Dress

To become a warrior and earn the right to wear an eagle feather, young Native American men in some tribes had to perform a brave act for their tribe. For Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains like the Crow people, Cheyenne people, Lakota people, or Apache, this could include:

- Killing and scalping an enemy.

- Capturing a horse.

- Taking away an opponent's weapon.

- Sneaking into an enemy's camp.

- Taking a prisoner.

- Striking an opponent in battle without killing them.

Receiving an eagle feather was a very important step into manhood. After this, the warrior often took a new name. Few Native Americans received more than three eagle feathers in their lives because eagles were rare and sacred. But very brave and skilled warriors like Sitting Bull, Geronimo, or Cochise could earn enough feathers to make a full war bonnet.

Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains often decorated their buckskin war shirts. They used enemy scalps, bone breastplates for protection, bear claws, porcupine quills, or wolf teeth to show their hunting skills. They also used silver conchos made from old coins and beautiful glass beadwork. This clothing served two purposes: to scare their enemies and to make the warrior look his best for the Great Spirit if he died in battle. Common bead patterns, believed to protect the wearer, included the thunderbird, diamonds, crosses, or zigzags in colors like white, cyan, black, red, orange, and yellow.

Among tribes like the Pawnee, Iroquois, and Mohawk, warriors received a Mohican haircut as part of becoming a man. In these cultures, a brave could not shave his head until he had been in battle. Tattooing and scarification were also used by Southeastern tribes like the Cherokee, Seminole, and Cree. These showed a warrior's ability to resist pain, their loyalty to a tribe, or their marital status. They also hoped to gain favor from totem spirit animals like Raven, the Great Bear, or the serpent. Centuries before the first pioneers arrived, shamans would tattoo warriors using cactus spines dipped in a carbon-based ink.

Weapons of the Warriors

Close-Range Weapons

For close-up fighting, Native American warriors preferred sharp weapons like knives. Tomahawks were first carved from stone. But by the 1700s, warriors could get iron axes through trade. Some tomahawks had decorative star or heart shapes. The tomahawks of tribal chiefs sometimes even had a pipe bowl. Spears could be thrown or used as lances. Other common weapons included ball-topped clubs and gunstock war clubs. These clubs were often decorated with brass thumbtacks from old trunks that pioneers burned for firewood. Brave deeds were recorded by carving notches into the club or, less often, by adding an eagle feather.

Long-Range Weapons

The main long-range weapon for Native American warriors was the short, strong bow. It was designed for use on horseback and was deadly, but only at short distances. Guns were often hard to get, and ammunition was scarce for Native warriors. Because of this lack of ammunition and less training with firearms, the bow and arrow remained the preferred weapon.

However, after the American Civil War, firearms became much more common. The U.S. government, through the Indian Agency, would sell guns to Plains Indians for hunting. But unofficial traders would exchange guns for buffalo hides. Warriors in the First Nations Wars used many types of guns. These included flintlock horse pistols, long rifles, Colt revolvers, Springfield muskets, Remington rolling blocks, and Sharps carbines taken from the US cavalry. They also used repeating rifles like the Winchester yellowboy or Spencer carbine.

Serving the United States

United States Army Indian Scouts and trackers had worked for the U.S. government since the Civil War. During the Indian Wars, the Pawnee people, the Crow people, and the Tonkawa people allied with the American cavalry. They fought against their old rivals, the Apache and Sioux. Sgt. I-See-O of the Kiowa people was still serving in the army during World War I.

Lasting Legacy

Many Native Americans joined the American armed forces during World War I and World War II. For example, Joe Medicine Crow wore warpaint into battle. He was awarded eagle feathers and the rank of chief by his tribe's elders. This was because each of the four heroic deeds he did in Europe matched the traditional counting coup requirements.

The name Peace of the Braves has been used for several peace agreements with First Nations in Canada.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |