Battle of Franklin (1864) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Second Battle of Franklin |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Battle of Franklin, by Kurz and Allison (1891) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Ohio | Army of Tennessee | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 27,000 | 27,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,326 total

(189 killed,

1,033 wounded, 1,104 missing/captured) |

Schofield's estimate: 6,252 (1,750 killed, 3,800 wounded, 702 missing/captured) Hood's report: 4,500 |

||||||

The Second Battle of Franklin was a major fight during the American Civil War. It happened on November 30, 1864, in Franklin, Tennessee. This battle was a big disaster for the Confederate States Army.

Confederate General John Bell Hood led his Army of Tennessee in many attacks. They charged against strong defenses held by Union forces. These Union troops were led by General John Schofield. Even with many attacks, Hood could not stop Schofield from pulling his troops back. Schofield's army made an organized retreat to Nashville.

The Confederate attack involved about 20,000 soldiers. It was sometimes called the "Pickett's Charge of the West." This attack caused huge losses for the Confederate Army. Fourteen Confederate generals were killed, wounded, or captured. Fifty-five regimental commanders also became casualties. After this defeat, and another one at the Battle of Nashville, Hood's army was almost destroyed. It was no longer a strong fighting force.

This battle in 1864 was the second time fighting happened in Franklin. A smaller battle in 1863 was just a minor clash.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened: The Background

The Armies' Positions in 1864

After losing the Atlanta Campaign, General Hood wanted to draw the Union army into a fight. He hoped to cut off their supply lines. But Union General William Tecumseh Sherman decided to do something different. Sherman chose to march his main army away from its supply lines. This famous "Sherman's March to the Sea" meant his army would live off the land. Sherman believed this would save his men from constant attacks on their supply routes.

This left Hood's army without a direct enemy to chase. So, Hood decided to move his army north into Tennessee. His goal was to defeat parts of the Union army before they could gather. He also wanted to capture Nashville, a key supply center. Hood even hoped to get 20,000 new soldiers from Tennessee and Kentucky. Then, he planned to join up with General Robert E. Lee's army in Virginia. Many historians thought this plan was very unrealistic.

The job of defending Tennessee fell to Union General George Henry Thomas. He commanded about 30,000 soldiers. Another 30,000 Union troops were already in Nashville or moving towards it. Hood's army had about 39,000 men. This meant the Union forces in Tennessee were larger than Hood's invading army.

The Road to Franklin: November 21–29

Hood's army started marching north from Florence, Alabama, on November 21. They moved quickly and surprised the Union forces. The Union army was split into two groups, about 75 miles apart. Hood tried to get between them to defeat each group separately.

But Union General Schofield reacted fast. He quickly pulled his troops back from Pulaski to Columbia. Columbia had an important bridge over the Duck River. Schofield's men reached Columbia and built defenses just hours before the Confederates arrived. For several days, Schofield managed to block Hood at this river crossing.

On November 29, Hood sent some of his troops on a flanking march. They crossed the Duck River east of Columbia. This move put Schofield's army in great danger. His troops were split up, with some in Spring Hill and others marching from Columbia.

That afternoon and night, Hood had a perfect chance to attack Schofield's army. His forces had already reached the main road that separated the Union troops. However, due to mistakes by Hood's commanders, the Confederates failed to stop Schofield. By dawn on November 30, all Union troops and their supply wagons had passed Spring Hill safely. They soon reached Franklin, about 12 miles north. Hood was very angry when he found out Schofield had escaped. He ordered his army to chase them to Franklin.

Union Plans for Defense

Schofield's first troops arrived in Franklin around 4:30 a.m. on November 30. General Jacob Dolson Cox quickly started preparing strong defenses. They used old trenches from a previous battle in 1863.

Schofield decided to defend Franklin with his back to the Harpeth River. He had no special bridges to cross the river easily. He needed time to fix the main bridges over the river. One wagon bridge was burned, and a railroad bridge needed planks. His engineers worked to fix these bridges. By the time the battle started, almost all the Union supply wagons had crossed the river.

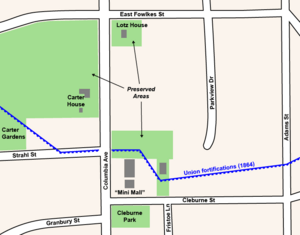

By noon, the Union defenses were ready. They formed a half-circle around the town. The other half of the circle was the Harpeth River. The defenses were very strong. They included a ditch, a wall of earth and rails, and a deep trench for soldiers. Just behind the center of the line was the Carter House. This building became General Cox's headquarters.

Two Union brigades were placed about half a mile in front of the main line. Their commander, General George D. Wagner, ordered them to dig in. However, one of his colonels, Emerson Opdycke, thought this was a bad idea. Opdycke moved his brigade behind the main Union line as a reserve.

Schofield thought Hood would try to go around his army, not attack directly. He didn't expect Hood to be so bold as to attack such strong defenses.

Hood's Arrival and His Plan

Hood's army arrived on Winstead Hill, about two miles south of Franklin, around 1:00 p.m. Hood decided to launch a direct attack. This decision surprised and worried his top generals. General Nathan Bedford Forrest suggested flanking Schofield instead. General Frank Cheatham told Hood, "I do not like the looks of this fight; the enemy has an excellent position and is well fortified."

But Hood believed it was better to fight Schofield now. He thought Schofield's defenses were weaker than those in Nashville. General Patrick Cleburne also saw the strong enemy defenses. But he told Hood he would either take the enemy's positions or die trying.

Some stories say Hood was angry about Schofield's escape from Spring Hill. They say he wanted to punish his army by ordering a risky attack. However, more recent studies suggest Hood was determined, not angry. His main goal was to crush Schofield's army before it could reach Nashville. He worried that trying to go around Schofield would take too long.

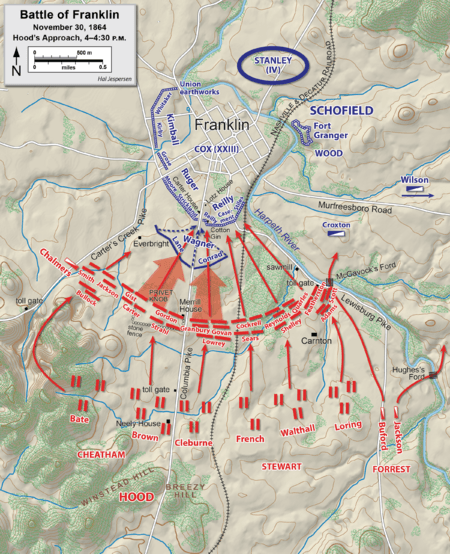

The Confederate attack began at 4:00 p.m. It was getting dark, as sunset was at 4:34 p.m. Hood's attacking force was about 19,000 to 20,000 men. They had to cross two miles of open ground. They had very little artillery support. Many thought this force was too small for such a difficult mission.

Who Fought: The Armies

Union Forces

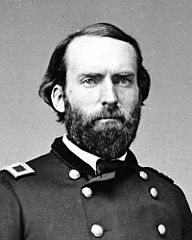

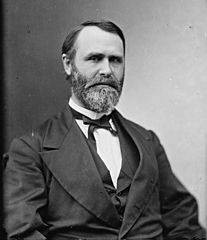

| Key Union Leaders |

|---|

|

General John Schofield led about 27,000 Union soldiers. His forces included:

- The IV Corps, led by General David S. Stanley.

- The XXIII Corps, led by General Jacob Dolson Cox.

- The Cavalry Corps, led by General James H. Wilson.

Confederate Forces

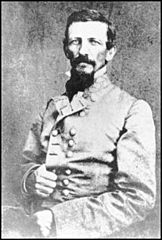

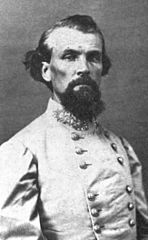

| Key Confederate Leaders |

|---|

|

General John Bell Hood commanded the Army of Tennessee. This was the second largest Confederate army. It had about 39,000 men in total. At Franklin, about 27,000 Confederates fought. Key commanders included:

- General Benjamin F. Cheatham

- General Stephen D. Lee

- General Alexander P. Stewart

- Cavalry forces under General Nathan Bedford Forrest

The Battle Begins

First Attacks and Union Retreat

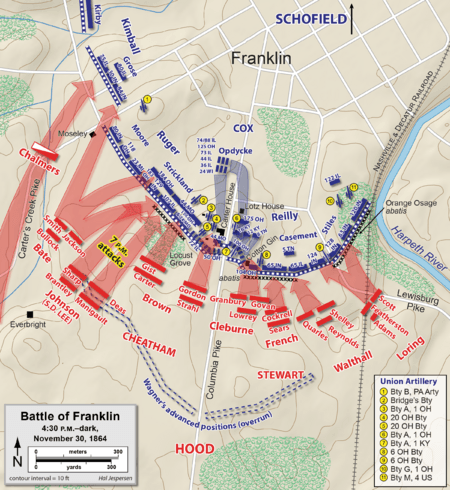

Hood's attack first hit about 3,000 Union soldiers. These men were in two brigades under Colonels Lane and Conrad. They tried to hold their ground but quickly broke under the pressure. Many Union soldiers ran back towards their main defenses. The Confederates chased them closely, shouting, "Go into the works with them!" The Union and Confederate soldiers became mixed together. This made it hard for the defenders to shoot without hitting their own men.

Confederates Break Through, Then Are Pushed Back

The Union defenses had a weak spot where the main road entered town. Confederate divisions pushed into this opening. Some of their troops broke through the Union lines. In just a few minutes, Confederates had moved 50 yards deep into the Union center.

As more Confederates poured into the gap, Colonel Emerson Opdycke's Union brigade was waiting in reserve. Opdycke quickly moved his men into a fighting line. They met fleeing Union soldiers being chased by Confederates. Opdycke ordered his brigade to charge forward to the defenses. At the same time, General David Stanley, his corps commander, arrived. Stanley saw Opdycke doing exactly what was needed to save the line. Stanley's horse was shot, and he was wounded, but he saw the counterattack begin.

Opdycke's counterattack, joined by other Union reserves, closed the gap. Fierce hand-to-hand fighting happened around the Carter House. Soldiers used bayonets, rifle butts, and even shovels. Fighting continued for hours around the Carter House. Many Confederate soldiers were trapped near the Union defenses. They couldn't advance or retreat. Confederate losses were very high in this area. General Cleburne was killed, and many of his commanders were also casualties.

Some Union soldiers had special repeating rifles. These rifles could fire many shots quickly. This gave the defenders a big advantage over the Confederates.

Attacks on the Union Left Fail

While the center was fighting, Confederate troops also attacked the Union left. The land here was narrow, which made it hard for the Confederate brigades to stay organized. They also faced heavy artillery fire from the main Union line and from Fort Granger across the river. Thick thorny bushes also made it hard to advance.

Confederate attacks were pushed back with heavy losses. General John Adams tried to rally his brigade by riding his horse directly onto the Union defenses. He and his horse were both shot and killed. Other Confederate brigades also tried to attack multiple times but were pushed back.

Problems on the Confederate Left

General William B. Bate's Confederate division had a long way to march to reach its target. By the time they attacked, it was almost dark. Bate's left side was not protected as he expected. This left his troops open to enemy fire. Neither Bate nor the cavalry on his flank made any progress.

Hood, still at his headquarters, believed he could still break the Union line. Around 7 p.m., he sent another Confederate division to help. But these new troops were unfamiliar with the area in the dark. They also had trouble attacking the defenses and were pushed back with heavy losses.

Cavalry Fights

On the east side of the river, Confederate cavalry commander Nathan Bedford Forrest tried to go around the Union left. His cavalry crossed the Harpeth River. When Union cavalry commander General James H. Wilson learned this, he ordered his troops to attack Forrest. Union cavalry, fighting on foot, pushed the Confederates back across the river. Some Union cavalry had special seven-shot carbines. These weapons were very effective. Wilson was proud because this was the first time Forrest had been defeated by a smaller force in a direct fight during the war.

What Happened Next: The Aftermath

After the last Confederate attack failed, Hood decided to stop fighting for the night. He planned to attack again in the morning. But General Schofield ordered his Union infantry to cross the river, starting at 11 p.m. Schofield had orders from General Thomas to leave Franklin. He was happy to follow these orders, even though the battle had changed things. The Union army reached Nashville by noon on December 1. Hood's damaged army followed them.

The Confederates were left in control of Franklin, but their enemy had escaped again. Hood had not been able to destroy Schofield's army or stop its retreat to Nashville. This failure came at a terrible cost. The Confederates suffered 6,252 casualties. This included 1,750 killed and 3,800 wounded. Many more had less serious wounds.

More importantly, the Confederate leadership in the West was severely hurt. General Patrick Cleburne, considered one of the best division commanders, was killed. Fourteen Confederate generals were killed, wounded, or captured. Fifty-five regimental commanders were also casualties. Among the dead was Tod Carter, a local boy who had joined the Confederate army. He was wounded just a few hundred yards from his home and died the next day.

Union losses were much lower: 189 killed, 1,033 wounded, and 1,104 missing. Many Union wounded were left behind in Franklin. They were later rescued when Union forces returned.

The Army of Tennessee was badly damaged at Franklin. Despite this, Hood decided to march his remaining 26,500 men towards Nashville. There, General Thomas had more than 60,000 well-defended Union troops. Hood's army was outnumbered and exposed. Thomas attacked Hood on December 15–16 at the Battle of Nashville. Hood's army was completely defeated and chased back to Mississippi with less than 20,000 men. The Army of Tennessee never fought effectively again. Hood's career was ruined.

Some Confederate soldiers surprisingly thought Franklin was a victory. But one soldier, Joseph Boyce, who was wounded, said, "two such victories will wipe out any army." Historian James M. McPherson wrote that Hood's army "had shattered itself beyond the possibility of ever doing so again."

Visiting the Battlefield Today

The Carter House still stands today. It was at the center of the Union defenses. You can visit it and see hundreds of bullet holes on the buildings. The Carnton Plantation was a home during the battle. It became the largest field hospital after the fighting. Many wounded soldiers were treated there. Next to Carnton is the McGavock Confederate Cemetery. Here, 1,481 Southern soldiers killed in the battle are buried.

Much of the Franklin battlefield has been built over. For example, where General Cleburne fell was once a Pizza Hut restaurant. But now, city officials and history groups are working to save what is left of the land.

Since 2005, more land has been bought to create a battlefield park. The old Pizza Hut site is now Cleburne Park. The land where the Carter Cotton Gin stood has also been purchased. Preservation groups plan to rebuild the cotton gin and some of the old Union trenches.

In 2010, the State of Tennessee gave money to buy more land. Local groups are also trying to buy more acres of the battlefield. The American Battlefield Trust and its partners have saved over 178 acres of the battlefield since 1996.

In Popular Culture

In the famous book "Gone with the Wind" by Margaret Mitchell, the character Rhett Butler says he fought at Franklin.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |