Anglo-Irish people facts for kids

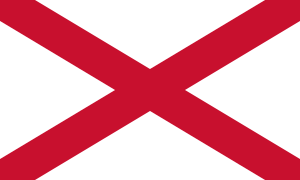

St Patrick's Cross is often seen as a symbol of the Anglo-Irish.

|

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Northern Ireland | 407,454 (Northern Irish Anglicans) (Northern Irish Methodists) (Other Northern Irish Protestants) |

| Republic of Ireland | 177,200 (Irish Anglicans) (Irish Methodists) (Other Irish Protestants) |

| Languages | |

| Standard English, Hiberno-English | |

| Religion | |

| Anglicanism (some Methodist, Catholic or other Protestant) (see also Religion in Ireland) |

|

| Related ethnic groups | |

| English, Irish, Scotch-Irish Americans, Scots, Ulster Scots, Ulster Protestants, Welsh | |

The Anglo-Irish people (Irish: Angla-Éireannach) are a group of people in Ireland. They are mostly descendants of English Protestants who settled there. Most of them belong to the Church of Ireland. This church was the official church of Ireland until 1871. Some also belonged to other Protestant churches, like the Methodist church. A few were even Roman Catholics.

Anglo-Irish people often saw themselves as "British." Less often, they called themselves "Anglo-Irish," "Irish," or "English." Many became important leaders in the British Empire. They also served as senior army and navy officers. This was because the Kingdom of England and Great Britain were closely linked with the Kingdom of Ireland until 1800. Then, they united to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

The term "Anglo-Irish" usually does not include Presbyterians in Ulster. Their families mostly came from Lowland Scotland, not England or Ireland. These people are sometimes called Ulster-Scots. Anglo-Irish people have different political ideas. Some were strong Irish Nationalists, wanting Ireland to be independent. But most were Unionists, wanting to stay part of the United Kingdom. While many Anglo-Irish came from English families who moved to Ireland, some were also descendants of old Gaelic Irish families.

Contents

Who Were the Anglo-Irish as a Social Group?

The term "Anglo-Irish" often describes members of the Church of Ireland. These were the professional and land-owning class in Ireland. They were powerful from the 1600s until Ireland became independent in the early 1900s. During the 1600s, this Anglo-Irish land-owning class took the place of the old Gaelic Irish and Old English ruling families. They were also called "New English" to tell them apart from the "Old English." The Old English were descendants of medieval Hiberno-Norman settlers.

Under the Penal Laws, which were in effect from the 1600s to the 1800s, Roman Catholics faced many restrictions. They could not hold public office. In Ireland, they could not attend Trinity College Dublin or work in professions like law or medicine. They also could not join the military. The lands of Roman Catholic landowners who refused to take certain oaths were often taken away. Their rights to inherit land were also limited. If they changed their religion to the Church of Ireland, they could usually keep or get back their property. This was because loyalty was seen as the main issue. In the late 1700s, the Parliament of Ireland in Dublin gained more independence. Then, efforts began to remove these strict laws.

Not all Anglo-Irish people came from English Protestant settlers. Some had Welsh roots. Others were descendants of Old English or even native Gaelic families who became Anglican. Members of this ruling class often called themselves Irish. But they kept English customs in politics, business, and culture. They enjoyed popular English sports like racing and fox hunting. They also married into ruling families in Great Britain. Many successful Anglo-Irish people spent their careers in Great Britain or other parts of the British Empire. They built large country houses, known in Ireland as Big Houses. These houses became a symbol of their power in Irish society.

The writer Elizabeth Bowen described her experience as feeling "English in Ireland, Irish in England." She felt she did not fully belong to either place.

What Businesses Did Anglo-Irish Families Own?

In the early 1900s, Anglo-Irish families owned many major businesses in Ireland. These included famous companies like Jacob's Biscuits and Bewley's. They also owned Jameson's Whiskey and Guinness, which was Ireland's largest employer. They controlled financial companies too, such as the Bank of Ireland.

Famous Anglo-Irish People

Many famous people came from Anglo-Irish families.

- Writers: Oscar Wilde, Jonathan Swift, Bram Stoker (who wrote Dracula), J. M. Synge, W. B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, C. S. Lewis (who wrote The Chronicles of Narnia), and Samuel Beckett.

- Scientists: In the 1800s, many top scientists in the British Isles were Anglo-Irish. These included Sir William Rowan Hamilton and Sir George Stokes. In the 1900s, Ernest Walton, a Nobel Prize winner, was also Anglo-Irish. The polar explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton was another famous Anglo-Irish scientist.

- Politicians: Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Henry Grattan, and Charles Stewart Parnell were important figures in British politics.

- Military Leaders: Many Anglo-Irish men became senior officers in the British Army. These included Field Marshal Earl Roberts and the 1st Duke of Wellington, who defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo.

- Artists and Musicians: Famous artists included sculptor John Henry Foley and painter William Orpen. Ballerina Dame Ninette de Valois and designer Eileen Gray were also well-known. Composers like Charles Villiers Stanford created classical music.

Henry Ford, the American car maker, was half Anglo-Irish. His father was born in Cork, Ireland.

Anglo-Irish Views on Ireland's Independence

Most Anglo-Irish people, as a group, did not want Ireland to be independent. They were against Home Rule, which would have given Ireland more self-government. They mostly supported Ireland staying united with Great Britain. This union lasted from 1800 to 1922. There were many reasons for this. The union brought economic benefits to landowners. Anglo-Irish families also had close ties with the British government. They held important political positions in Ireland under the union. Many Anglo-Irish men served as officers in the British Army. Many were also clergymen in the Church of Ireland. These factors encouraged them to support unionism. From the mid-1800s to 1922, the Anglo-Irish were the main supporters of unionist groups in Ireland.

However, not all Protestants in Ireland, or Anglo-Irish people, wanted to stay united with Great Britain. For example, the writer Jonathan Swift, a Church of Ireland clergyman, spoke out against the difficulties faced by ordinary Irish Catholics. Reformist politicians like Henry Grattan, Wolfe Tone, and Charles Stewart Parnell were also Protestant nationalists. They often led the movement for Irish independence. The Irish rebellion of 1798 was led by some Anglo-Irish and Ulster Scots people. They worried about the political effects of uniting with Great Britain.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, Irish nationalism became more linked to a Roman Catholic identity. Still, some Anglo-Irishmen in southern Ireland realized that a political agreement with Irish nationalists was needed. Politicians like Sir Horace Plunkett worked to find a peaceful solution to the "Irish question."

During the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921), many Anglo-Irish landowners left Ireland. Their family homes were often attacked and burned. These attacks continued during the Irish Civil War. Many Anglo-Irish people felt the new Irish State could not protect them. They feared unfair laws and social pressure. So, many left Ireland for good, often moving to Great Britain. The number of Protestants in the Irish Free State dropped from 10% to 6% in the 25 years after independence.

The Anglo-Irish had mixed feelings about the Anglo-Irish Treaty. This treaty led to the creation of the Irish Free State. In 1921, the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin, J. A. F. Gregg, said that everyone should be loyal to the new Irish Free State.

In 1925, the Irish Free State was going to ban divorce. The Anglo-Irish poet W. B. Yeats gave a famous speech in the Irish Senate. He spoke proudly of his group, saying they were "no petty people" and had created much of Ireland's modern literature and political ideas.

Today, the term "Anglo-Irish" is not as commonly used to describe Protestants of English descent in southern Ireland.

Anglo-Irish Peers and Nobility

After the English won the Nine Years' War (1594–1603), the old Gaelic Irish nobility lost their power. This happened especially during the time of Oliver Cromwell. By 1707, after more wars and the union of England and Scotland, the powerful families in Ireland were mostly Anglican. These families were loyal to the Crown. Some were Irish families who had joined the Church of Ireland. They kept their lands and special rights, like the Dukes of Leinster. Others were families of British or mixed British background who gained their status from the Crown, like the Earls of Cork.

Here are some important Anglo-Irish peers:

- The 1st Earl of Cork: He was a powerful official in Ireland and the father of scientist Robert Boyle.

- The 1st Baron Glenavy: He was the last Lord Chancellor of Ireland and the first Chairman of the Irish Senate.

- The 3rd Earl of Iveagh: From the famous Guinness family, he was a member of the Irish Senate.

- The 3rd Earl of Rosse: An astronomer who built the largest telescope in the world at the time.

- The 18th Baron of Dunsany: A well-known author.

- The 1st Duke of Ormonde: A 17th-century leader who served as Lord Deputy of Ireland.

- The 1st Duke of Wellington: A famous general who defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo. He later became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

Before 1800, all Irish peers had a seat in the Irish House of Lords in Dublin. After 1800, under the Act of Union, the Irish Parliament was closed. Irish peers could then elect 28 of their members to sit in the British House of Lords in London. During the Georgian Era, British kings often gave Irish peerage titles to Englishmen. This was sometimes done to avoid making the British House of Lords too big.

Some Anglo-Irish peers have been chosen by Presidents of Ireland to serve on their advisory Council of State.

See also

In Spanish: Anglo-Irlandés para niños

In Spanish: Anglo-Irlandés para niños

- Normans in Ireland

- Surrender and regrant

- Hiberno-English

- Ulster Scots people

- Plantation of Ulster

- Unionism in Ireland

- Catholic Unionist

- Protestant Irish nationalists

- Souperism

- English diaspora

- Reform Movement

- Confederate Ireland

- Jacobitism

- Irish Unionist Alliance

- West Brit

- Ireland–United Kingdom relations

- Irish migration to Great Britain

- Baron Baltimore

- Derry

- Miler Magrath

- Samuel Beckett

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |