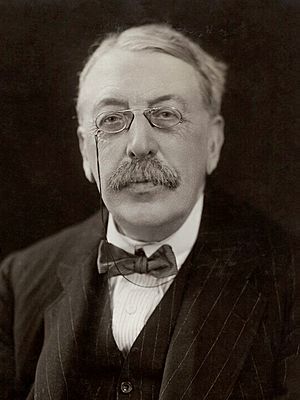

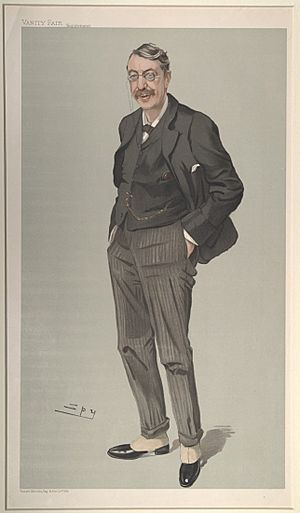

Charles Villiers Stanford facts for kids

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (born September 30, 1852 – died March 29, 1924) was a famous Anglo-Irish composer, music teacher, and conductor. He lived during the late Romantic era of music. Stanford came from a wealthy and very musical family in Dublin, Ireland. He studied at the University of Cambridge and then learned music in Leipzig and Berlin. He played a big part in making the Cambridge University Musical Society much better, inviting famous musicians from around the world to perform with them.

Even before he finished university, Stanford became the organist at Trinity College, Cambridge. In 1882, when he was 29, he helped start the Royal College of Music. He taught composition there for the rest of his life. From 1887, he was also a Professor of Music at Cambridge. As a teacher, Stanford preferred classical music, like the works of Brahms. He didn't really like very modern music. Some of his students became even more famous than him, including Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams. As a conductor, Stanford led the Bach Choir and the Leeds music festival.

Stanford wrote many concert pieces, including seven symphonies. But his most remembered works are his choral pieces for church, mostly in the Anglican style. He loved composing operas, but none of his nine finished operas are widely performed today. Some music experts thought Stanford, along with Hubert Parry and Alexander Mackenzie, helped bring back great music in the British Isles. However, after being very successful in the late 1800s, his music became less popular in the 1900s, especially compared to Edward Elgar and his own former students.

Stanford's Life

Early Years in Dublin

Charles Stanford was born in Dublin, Ireland. He was the only son of John James Stanford and his second wife, Mary. His father was a well-known lawyer and his mother was a talented piano player. Both of his parents loved music. His father, John, was a cellist and a great singer. He even sang the main part in Mendelssohn's Elijah when it was first performed in Ireland. Mary Stanford was a charming lady who could play difficult piano concertos.

Young Charles went to a private school in Dublin. His parents strongly supported his early musical talent. He had many teachers for violin, piano, organ, and composition. One of his teachers, Elizabeth Meeke, taught him to read music very well before he was twelve. She made him play a Mazurka by Chopin every day without stopping for mistakes. This helped him become a great sight-reader. One of his first songs, written when he was eight, was performed in a play three years later. At age seven, Stanford gave a piano concert, playing music by famous composers like Beethoven and Mozart.

In the 1860s, famous musicians sometimes visited Dublin. Stanford got to hear great performers like Joseph Joachim and Adelina Patti. He also loved seeing operas when the Italian Opera Company visited from London. When he was ten, his parents took him to London. There, he took composition lessons from Arthur O'Leary and piano lessons from Ernst Pauer. Later, he met the composer Arthur Sullivan and the writer George Grove, who became important in his career.

Charles's father wanted him to become a lawyer. But he agreed to let Charles study music, as long as he went to a regular university first. Stanford went to Queens' College at Cambridge University in 1870. He had already written many pieces of music by then.

Time at Cambridge University

Stanford spent a lot of time on music at Cambridge, sometimes more than his regular studies. He wrote religious and non-religious songs, a piano concerto, and music for a play. In 1870, he played the piano with the Cambridge University Musical Society (CUMS). He quickly became their assistant conductor. This music group was not very good at the time. Its choir only had men and boys, which limited the music they could perform. Stanford wanted women to join, but the members disagreed. So, in 1872, he started a new choir with both men and women. This new choir was so good that CUMS quickly changed its mind and merged with Stanford's choir. Women were then allowed to join CUMS.

The main conductor of CUMS became ill, so Stanford took over in 1873. He also became the deputy organist at Trinity College. In the summer of 1873, Stanford traveled to Europe for the first time. He went to a festival in Bonn, Germany, where he met famous composers Joseph Joachim and Brahms. Stanford loved the music of Brahms and Schumann. He also admired Wagner's opera Die Meistersinger.

When the main organist at Trinity College passed away, Stanford was asked to take his place. He agreed, but only if he could still go to Germany each year to study music. Two days after getting the job, Stanford took his final exams for his classics degree. He passed, but just barely!

Studying in Germany

In 1874, Stanford went to Leipzig to study with Carl Reinecke. Reinecke was a composition and piano professor. However, Stanford found Reinecke to be very old-fashioned and not inspiring. Reinecke didn't like any modern composers like Wagner or Brahms. Stanford's biographer, Paul Rodmell, thinks this might have been good for Stanford. It might have made him want to try new things. Stanford also took piano lessons from Robert Papperitz, who he found more helpful.

After a second trip to Leipzig, Stanford went to Berlin in 1876. He studied with Friedrich Kiel, who he found to be a much better teacher. Stanford said he learned more from Kiel in three months than from all his other teachers in three years.

A Rising Composer

While studying in Germany, Stanford kept working with CUMS in Cambridge. In 1876, they performed one of the first British performances of the Brahms Requiem. In 1877, CUMS became nationally famous when they performed Brahms's First Symphony for the first time in Britain.

Stanford was also becoming known as a composer. In 1875, his First Symphony won second prize in a competition. In the same year, he led the first performance of his oratorio The Resurrection. He also wrote music for Alfred Tennyson's play Queen Mary in 1876.

In 1878, Stanford married Jane Anna Maria Wetton, a singer he met in Leipzig. They had a daughter, Geraldine, in 1883, and a son, Guy, in 1885.

Stanford wrote his first opera, The Veiled Prophet, in 1878. It was based on a poem by Thomas Moore. An opera manager suggested he try to get it performed in Germany first. The opera was performed in Hanover, Germany, in 1881. Reviews were mixed, and it wasn't performed in England until 1893. Stanford kept trying to write successful operas throughout his life.

By the early 1880s, Stanford was a very important person in British music. He helped his friend Hubert Parry get recognition by asking him to write music for a play and a symphony for CUMS. Stanford continued to make CUMS famous by bringing in top international musicians like Joachim and Hans Richter. He also improved the music at Trinity College, writing beautiful church music.

In the early 1880s, Stanford worked on two more operas, Savonarola and The Canterbury Pilgrims. Savonarola was well-received in Germany but not in London. Critics said it was not dramatic enough. The Canterbury Pilgrims had a better reception, but some critics felt it lacked emotion and sounded too much like Wagner's Die Meistersinger.

Becoming a Professor

In 1883, the Royal College of Music (RCM) was founded. The director, George Grove, wanted the new college to train professional musicians well. Stanford was a key helper in this. He believed a good college orchestra was important for composition students. He also saw how much better German orchestras were than British ones. Stanford became the professor of composition and a conductor of the college orchestra. He held this job for the rest of his life. Many of his students became famous composers, including Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Gustav Holst, Ralph Vaughan Williams, John Ireland, and Rebecca Clarke.

Stanford was a strict teacher. He taught students one-on-one and made them work hard. One student said that if you were sloppy, you would be in big trouble! Many of his students, like Holst and Vaughan Williams, developed their own styles, different from Stanford's classical approach. This was a bit like how Stanford himself had moved away from his own conservative teacher. Even though his students became more famous, Stanford's teaching was very important. He also started an opera class at the RCM, with an opera production every year.

In 1887, Stanford became the professor of music at Cambridge University. He worked to make sure that only students who had studied at Cambridge for three years could get music degrees from the university.

Conductor and Composer

In the late 1800s, Stanford continued to compose and perform, even with his teaching duties. In 1885, he became the conductor of the Bach Choir in London, a job he held until 1902. His Irish Symphony was performed in Germany, Austria, and even New York by famous conductors like Hans von Bülow and Mahler. He also wrote music for plays at the Theatre Royal, Cambridge. Critics praised his music for being dramatic and having a unique style.

In the 1890s, the writer George Bernard Shaw had mixed feelings about Stanford's music. Shaw liked Stanford's lively, Irish-sounding pieces but didn't like his serious church music as much. Shaw even suggested that Stanford should write comic operas like Arthur Sullivan.

Stanford returned to opera in 1893 with a revised version of The Veiled Prophet. His friend, J. A. Fuller Maitland, who was a music critic, praised it highly. Stanford's next opera was Shamus O'Brien (1896), a comic opera. It was very successful, running for 82 performances. The young conductor Henry Wood conducted it.

In 1894, Hubert Parry became the new director of the Royal College of Music. Stanford and Parry, once good friends, started to argue often. Stanford was known for being hot-tempered.

In 1898, Stanford became the conductor of the Leeds triennial music festival, taking over from Arthur Sullivan. He held this position until 1910. For the festival, he composed works like Songs of the Sea (1904) and Songs of the Fleet (1910). He also featured new works by other composers, including his former students, like Vaughan Williams's A Sea Symphony.

The 20th Century and Later Years

In 1901, Stanford wrote another opera, Much Ado About Nothing, based on Shakespeare's play. Critics praised how well it captured the spirit of the original.

However, Stanford's fame began to fade in the early 1900s. The music of Edward Elgar became much more popular. Stanford had supported Elgar earlier, but he became upset when Elgar's success overshadowed his own. They had some disagreements, and Stanford even wrote critical remarks about Elgar in his book A History of Music.

Despite this, Stanford continued to compose. Between 1900 and 1914, he wrote a violin concerto, a clarinet concerto, and his last two symphonies. In 1916, he wrote his opera The Critic, which was well-received.

The First World War (1914-1918) deeply affected Stanford. He was scared by air raids and had to move out of London. Many of his former students were hurt or killed in the war. His income also dropped. His relationship with Parry became very strained. However, when Parry died in 1918, Stanford worked hard to ensure he was buried in St Paul's Cathedral.

After the war, Stanford taught less but continued to give public lectures. In 1921, he conducted his last public performance, a new cantata called At the Abbey Gate. Reviews were polite but not very excited.

In September 1922, Stanford finished his final work, the sixth Irish Rhapsody. Two weeks later, he celebrated his 70th birthday. His health then declined. He had a stroke in March 1924 and died later that month. He was cremated, and his ashes were buried in Westminster Abbey next to other great composers like Henry Purcell. His last opera, The Travelling Companion, was performed after his death.

Awards and Honours

Stanford received many awards and honorary doctorates from universities like Oxford and Cambridge. He was made a knight by King Edward VII in 1902, which meant he was called "Sir Charles." In 1904, he became a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin.

Stanford's Music

Stanford wrote about 200 pieces of music. These include seven symphonies, around 40 choral works, nine operas, 11 concertos, and 28 chamber works. He also wrote many songs, piano pieces, and organ works. He was known for his excellent technical skills in composing. Another composer, Edgar Bainton, said that Stanford was a "master of means" and that everything he wrote "comes off" well.

After Stanford died, most of his music was quickly forgotten. Only his church music remained popular. His Stabat Mater and Requiem were still performed. His two sets of sea songs and the song The Blue Bird were also sometimes heard. However, in recent years, more of his music has been recorded and is being rediscovered. Many people used to say his music sounded too much like Brahms, but recordings show it has its own unique qualities.

A common criticism of Stanford's music is that it sometimes lacks strong emotion. Some critics felt that his serious works, especially his operas, didn't always convey love or deep feelings very well.

Orchestral Music

Stanford's seven symphonies show both the strengths and limits of his music. They are very well-structured and expertly put together, but they often sound similar to the styles of Mendelssohn, Schumann, and Brahms. However, his symphonies are still worth exploring because of their clever forms and skillful use of instruments.

His First Symphony was written for a competition and won second prize, but it was only performed once during his lifetime.

The Third Symphony, called the Irish Symphony, was first performed in 1887. It was conducted by Mahler in New York in 1911. This symphony remained the most popular of Stanford's symphonies during his life. It is full of the spirit and tunes of Ireland, with joyful and sad parts. Stanford often used real Irish folk tunes in his music.

Stanford usually avoided music that tells a specific story (called programmatic music). But his Sixth Symphony, written in memory of the artist G. F. Watts, was inspired by Watts's sculptures and paintings.

Among his other orchestral works are his six Irish Rhapsodies, written in the 1900s. Two of these feature a solo instrument with the orchestra: the third for cello and the sixth for violin.

Chamber Music

Stanford's chamber music (music for a small group of instruments) is well-crafted but not widely known. Some notable pieces include the Three Intermezzi for clarinet and piano (1879), the Serenade (Nonet) of 1905, and the Clarinet Sonata (1911). His First String Quintet is described as warm and rich-sounding, built in a classical style.

Church Music

While much of Stanford's music is forgotten, many of his church pieces are still popular. He helped make settings of Anglican church services important artistic works again. His services in A (1880), F (1889), and C (1909) are still important parts of church music today. Like his concert works, his church music focuses on melody.

Operas

Critics have different opinions on Stanford's operas. Some say Shamus O'Brien lacks strong tunes. The Critic is seen by some as one of his best operas, with fresh and melodious music. Much Ado About Nothing is also praised for having some of his best opera music. His last opera, The Travelling Companion, is considered by some to be his finest opera. It has a unique atmosphere that could help improve Stanford's reputation as an opera composer.

Recordings

Even though much of Stanford's music isn't often played in concert halls, a lot of it has been recorded. You can find complete sets of his symphonies on CD. Other recorded orchestral works include his Irish Rhapsodies and his clarinet and piano concertos. Of his nine operas, only The Travelling Companion has a full recording available.

Stanford's church music is very well represented on recordings. There are many versions of his services and motets. His Mass in G Major was first recorded in 2014.

The Cambridge Singers choir released an album of Stanford's sacred and secular works in 1992. The first CD dedicated to his partsongs (songs for multiple voices) came out in 2013.

Stanford also wrote about 200 art songs and 300 folk songs for concerts. Famous singers like Janet Baker and Kathleen Ferrier have recorded his songs. More recent recordings focusing on his songs have also been released.

Many of his chamber works, like the Three Intermezzi for Clarinet and Piano, have been recorded. All eight of his string quartets and his two string quintets are now available on recordings. The complete piano music has also been recorded.

The Stanford Society

The Charles Villiers Stanford Society was started in 2007 by music fans and experts. Its goal is to encourage more interest and research into Stanford's life and works. The society also supports performances and recordings of his less well-known pieces.

The society has helped with the first performances and recordings of some of Stanford's works. This includes the first-ever recording of his last opera, The Travelling Companion.

See also

In Spanish: Charles Villiers Stanford para niños

In Spanish: Charles Villiers Stanford para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |