Thomas Moore facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Moore

|

|

|---|---|

Thomas Moore, after a painting by Thomas Lawrence

|

|

| Born | 28 May 1779 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 25 February 1852 (aged 72) Sloperton Cottage, Bromham, Wiltshire, England |

| Occupation | Writer, poet, lyricist |

| Education | Samuel Whyte's English Grammar School, Dublin; Trinity College, Dublin; Middle Temple, London |

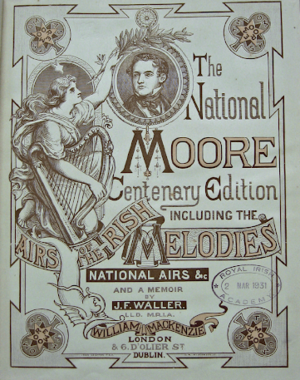

| Notable works | Irish Melodies Memoirs of Captain Rock Lalla Rookh Letters & Journals of Lord Byron |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Dyke |

Thomas Moore (born May 28, 1779 – died February 25, 1852) was a famous Irish writer, poet, and songwriter. He is best known for his collection of songs called Irish Melodies. These songs took old Irish tunes and added English words, helping to change popular Irish culture from speaking mostly Irish to speaking English. In England, people saw Moore as a political writer for the Whigs, a major political group. In Ireland, he was known as a supporter of Catholic rights.

Moore was married to Elizabeth Dyke, an actress. He was nicknamed "Anacreon Moore" because his early poems were like those of an ancient Greek poet who wrote about fun and parties. Even though he didn't always show strong religious feelings, Moore defended the Catholic Church in Ireland during important debates about Catholic Emancipation. This was about giving Catholics more rights.

His longer writings showed even stronger support for change. For example, his book Life and Death of Lord Edward Fitzgerald described the Irish leader as a hero who fought for democratic reform. Another book, Memoirs of Captain Rock, told the story of poor Irish tenants who were forced to rebel against their landlords.

Today, Thomas Moore is mostly remembered for his Irish Melodies, especially songs like "The Minstrel Boy" and "The Last Rose of Summer". Some also remember him for his role in the loss of his friend Lord Byron's personal writings.

Contents

Early Life and First Steps as a Writer

Thomas Moore was born in Dublin, Ireland, above his parents' grocery shop. His mother, Anastasia Codd, was from Wexford, and his father, John Moore, was from Kerry. He had two younger sisters, Kate and Ellen. From a young age, Thomas loved music and performing. He would put on musical plays with his friends and even hoped to become an actor.

He went to Samuel Whyte's school in Dublin, where he learned Latin and Greek, and became fluent in French and Italian. By the time he was 14, one of his poems was published in a new magazine called the Anthologia Hibernica (which means "Irish Anthology").

Samuel Whyte had also taught Richard Brinsley Sheridan, a famous Irish playwright and politician. Moore later wrote a book about Sheridan's life.

College Days and Irish Politics

In 1795, Thomas Moore was one of the first Catholics allowed to study at Trinity College, Dublin. His mother hoped he would become a lawyer. At Trinity, he became friends with Robert Emmett and Edward Hudson, who were involved in the political movements of the time. These movements were inspired by the French Revolution and the idea of a French invasion.

In 1797, with his friends' encouragement, Moore wrote an appeal to his fellow students. He urged them to oppose the British government's plan to unite Ireland with Great Britain. In April 1798, Moore was questioned at Trinity College. He was accused of being involved with the Society of United Irishmen, a group that wanted to change Ireland's government. However, he was found innocent.

Moore did not take the secret oath with Emmett and Hudson. He also did not take part in the rebellion of 1798 (he was home sick) or the plot for which Emmett was executed in 1803. Later, in a book about the United Irish leader Lord Edward Fitzgerald (published in 1831), Moore showed his support for their cause. He even expressed regret that a French invasion led by General Hoche failed to land in Ireland in 1796. Moore honored Emmett's sacrifice in his song "O, Breathe Not His Name" (1808). He also included hidden references to Emmett in his long poem "Lalla Rookh" (1817).

London Life and Early Success

In 1799, Moore continued his law studies in London at Middle Temple. He didn't have much money, but friends from the Irish community in London helped him. One of these friends was Barbara, the widow of Arthur Chichester, 1st Marquess of Donegall, a wealthy landowner.

In 1800, Moore published his translations of poems by Anacreon, which were about wine, women, and song. He dedicated this work to the Prince of Wales, who would later become King George IV. Meeting the Prince was a big moment for Moore, helping him become popular in London's high society and literary groups. His talent as a singer and songwriter greatly contributed to his success. That same year, he worked briefly as a writer for the comic opera The Gypsy Prince, which was performed at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket.

In 1801, Moore released a collection of his own poems called Poetical Works of the Late Thomas Little Esq.. These poems were quite daring for the time, celebrating kisses and embraces. While they were popular then, they became less so when social rules became stricter during the Victorian era.

Travels and Family Life

Visiting America and a Duel

In 1803, Moore reluctantly sailed from London to take a government job in Bermuda. This job was arranged by Lord Moira, a friend who was known for protesting against government actions in Ireland. Moore was to be the registrar of the Admiralty Prize Court. Although he was remembered as the island's "poet laureate" even in 1925, Moore found life in Bermuda quite boring. After six months, he hired someone else to do his job and left for a long trip across North America.

Just like in London, Moore met many important people in the United States, including President Thomas Jefferson. However, he didn't like the simple life of most Americans. He preferred to spend time with European aristocrats who had come to America to rebuild their wealth, and with powerful Federalists. He later admitted that these people gave him a "twisted" view of the new American republic.

After returning to England in 1804, Moore published Epistles, Odes, and Other Poems (1806). In 1809, he was chosen as a member of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia.

Marriage and Children

Between 1808 and 1810, Moore performed each year in Kilkenny, Ireland, in plays that mixed professional actors with high-society amateurs. He enjoyed playing funny roles in comedies like Sheridan's The Rivals. Among the professional actors was Elizabeth "Bessy" Dyke, who performed with her sister. In 1811, Moore married Bessy in St Martin-in-the-Fields, London.

Moore kept his marriage a secret from his parents for a while. This might have been because Bessy didn't have a dowry (money or property given by the bride's family), and the ceremony was Protestant. Bessy preferred a quiet life and avoided fashionable society so much that many of her husband's friends never met her. Those who did meet her thought very highly of her.

The couple first lived in London, then in the countryside in Kegworth, Leicestershire, and later near Lord Moira's home. Finally, they settled in Sloperton Cottage in Wiltshire, close to the home of another good friend, Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne. Their friends included Sheridan and John Philpot Curran.

Thomas and Bessy had five children, but sadly, none of them lived longer than their parents. Three girls died young, and both sons passed away as young men. One son, Thomas Landsdowne Parr Moore, fought in the British Army in Afghanistan and later with the French Foreign Legion in Algeria. He was dying of tuberculosis, a disease that affected the family, when he was killed in action in 1846. Despite these sad losses, Thomas and Bessy's marriage is generally seen as a happy one.

Dealing with Debt and Meeting Byron

In 1818, it was discovered that the person Moore had hired to do his job in Bermuda had stolen £6,000. This was a huge amount of money, and Moore was responsible for paying it back. To avoid going to debtor's prison, Moore left for France in September 1819. He traveled with Lord John Russell, who would later become a British Prime Minister and editor of Moore's journals. In Venice in October, Moore saw his friend Lord Byron for the last time. Byron gave Moore a manuscript of his personal writings, and Moore promised to publish them after Byron's death.

In Paris, Bessy and their children joined Moore. He had a busy social life, often meeting Irish and British travelers like Maria Edgeworth and William Wordsworth. However, he sometimes struggled to connect his Irish friends in exile with members of the British establishment. For example, in 1821, several Irish exiles refused to attend a St Patrick's Day dinner Moore organized in Paris. They didn't want to be there because Wellesley Pole Long, a nephew of the Duke of Wellington, was present.

Moore eventually learned that his Bermuda debt had been partly paid off with help from Lord Lansdowne. Moore quickly repaid Lord Lansdowne. After more than a year, the family returned to Sloperton Cottage.

Political Writings

Writing for the Whigs

To support his family, Moore started writing political articles for his Whig friends and supporters. The Whigs were a political group that had been divided by different opinions on the French Revolution. However, the actions of the Prince Regent, especially his public attempts to divorce Princess Caroline, made many people unhappy. This helped the Whigs find new unity.

Moore said that the Whigs themselves didn't give him much help. He believed there was as much selfishness among them as among their rivals, the Tories. But Moore had a good reason to turn against the Prince Regent: the Prince strongly opposed allowing Catholics into parliament. Moore's humorous criticisms of the Prince were published in The Morning Chronicle newspaper and later collected in a book called Intercepted Letters, or the Two-Penny Post-Bag (1813).

Criticizing Lord Castlereagh

Another person Moore often criticized was Lord Castlereagh, who was the Foreign Secretary. Castlereagh, originally a Presbyterian from Ulster who became an Anglican Tory, had been very harsh in putting down the United Irishmen. He also pushed the Act of Union through the Irish Parliament.

Moore made fun of Castlereagh's support for the old-fashioned ideas of Britain's European allies in works like Tom Crib's Memorial to Congress (1818) and Fables for the Holy Alliance (1823). These writings were like the political cartoons of the time. Moore's verse novel The Fudge Family in Paris (1818) was also very popular, leading him to write a sequel. This book tells the story of an Irish family working for Castlereagh in Paris. The family is joined by a tutor, Phelim Connor, an honest but disappointed Irish Catholic. His letters to a friend show Moore's own views.

Connor's letters often criticized Castlereagh. One main idea was that Castlereagh represented the problems Ireland brought to British politics because of the Union. Another idea was that Castlereagh had not been honest about supporting Catholic rights during the Act of Union. Connor suggested that Castlereagh had promised freedom to Catholics but then abandoned them once he got what he wanted.

Moore learned that Castlereagh was particularly upset by the tutor's verses in The Fudge Family. In 1811, an Irish publisher named Peter Finnerty was sentenced to 18 months in prison for saying similar things about Castlereagh.

The Memoirs of Captain Rock

As a political writer, Moore played a role similar to Jonathan Swift a century earlier. Moore admired Swift but felt he didn't care enough about the suffering of his Catholic countrymen. The Memoirs of Captain Rock might have been Moore's way of showing his connection to the ordinary Irish people, especially since he lived among wealthy English families.

The Memoirs tells the history of Ireland through the eyes of a fictional character, Captain Rock, who comes from a Catholic family that lost land over time. The history itself is real. As the story reaches the time of the Penal Laws, Captain Rock's family has become very poor farmers. They suffer under greedy Anglo-Irish landlords. Both Captain Rock and his father become leaders of groups like the "White-boys," who were tenant farmers who rebelled against tax collectors, scared landlords' agents, and fought against evictions.

This low-level farming rebellion continued through and beyond the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s. It was only after this terrible famine that British governments started to take responsibility for farming conditions. When Captain Rock was published in 1824, the main issue was not tenant rights but the final step of Catholic Emancipation: Castlereagh's broken promise to allow Catholics into parliament.

Letter to the Roman Catholics of Dublin

At the time of the Union, Castlereagh's promises of Catholic emancipation seemed believable because Irish Catholics would be a minority in a united kingdom. However, this promise was removed from the union laws. In England, people feared that Catholics, who were seen as controlled by Rome, could not be trusted with constitutional freedoms. Moore supported a "liberal compromise" suggested by Henry Grattan. This idea was to calm fears of "Popery" by giving the Crown a "veto" (the power to reject) over the appointment of Catholic bishops.

In an open Letter to the Roman Catholics of Dublin (1810), Moore pointed out that Irish bishops had been willing to agree to this practice, which was common in Europe. He argued that allowing some control over papal authority was part of Ireland's own tradition. He said that in the time of "her native monarchy," the Pope had no say in choosing Irish bishops. Moore believed that "slavish notions of papal authority" only grew after the English conquest. He felt that the Irish aristocracy had sought a "spiritual alliance" with Rome against the new "temporal tyranny" at home.

Moore argued that by resisting the king's approval and giving "their whole hierarchy to the Roman court," Irish Catholics were unnecessarily remembering times that everyone should forget. However, his arguments didn't convince Daniel O’Connell, who Moore called a "demagogue." O'Connell's strong stance made him the clear leader of the Catholic cause in Ireland.

Even when the Curia (the Pope's administration) itself suggested in 1814 that bishops should be "personally acceptable to the king," O'Connell was against it. He declared that it was better for Irish Catholics to "remain forever without emancipation" than to let the king and his ministers "interfere" with the Pope's appointment of Irish religious leaders. O'Connell believed that the unity of the church and the people was at stake. He feared that if bishops and priests were "licensed" by the government, they would be no more respected than the ministers of the established Church of Ireland.

When Catholic emancipation finally happened in 1829, O'Connell paid a price: the Forty-shilling freeholders lost their voting rights. These were the people who had defied their landlords to vote for O'Connell in the 1828 Clare by-election, showing strong protest against Catholic exclusion. The "purity" of the Irish church was maintained. Moore lived to see this special papal power influence the Irish church, leading to the appointment of Paul Cullen as Primate Archbishop of Armagh in 1850.

Travels of an Irish Gentleman in Search of a Religion

In 1822, the new Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin, William Magee, called for a "Second Reformation." He wanted to convert a majority of Irish people to the Protestant faith. English missionaries, carrying "religious tracts" for Irish peasants, became involved in this "bible war." Catholics, who joined together behind O'Connell in the Catholic Association, believed that Protestants were trying to convert people by offering food and housing during times of hunger and distress. They also thought that political interests were at play.

Moore's narrator in Travels of an Irish Gentleman in Search of a Religion (1833) is also fictional. He is a Catholic student at Trinity College, just like Moore had been. When he hears about Emancipation (the Catholic Relief Bill of 1829 passing), he exclaims, "Thank God! I may now, if I like, turn Protestant." He feels pressured by the idea that Catholics are "obstinate" and "unfit for freedom." Now that he is free from the "point of honour" that would have stopped him from leaving his church during sanctions, he decides to explore the ideas of the "true" religion.

As expected, the young man decides to stay true to his family's Catholic faith. He chooses not to trade "the golden armour of the old Catholic Saints" for "heretical brass." However, his argument wasn't about the truth of Catholic beliefs. It was about the inconsistencies and errors of the bible preachers. Moore later wrote that his goal was to show his "disgust" at how "most Protestant parsons assume... credit for being the only true Christians." He also disliked their "insolence" in calling all Catholics "idolators" and "Antichrist". Moore said that if his young man had found even a "particle" of their rejection of the Roman church's "corruptions" among early Christians, he would have been convinced. These "corruptions" included ideas like salvation by good works (not just faith), transubstantiation (the belief that bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ), and honoring saints, relics, and images.

Brendan Clifford, who edited Moore's political writings, described Moore's beliefs as "cheerful paganism" or at least a "choose-your-own-adventure" Catholicism. Moore seemed to prefer the parts of Catholicism that Protestantism hated: the music, the drama, the symbols, and the images. Even though his mother was a very religious Catholic, and he saw Catholicism as Ireland's "national faith," Moore seems to have stopped formally practicing his religion as soon as he went to Trinity College.

Biographies and Irish History

In 1825, Moore's Memoirs of the Life of Richard Brinsley Sheridan was finally published after nine years of work. It became very popular and helped Moore gain a good reputation among literary critics. This book also had a political side: Sheridan was not only a playwright but also a Whig politician and a friend of Fox. Moore thought Sheridan was not always a strong supporter of reform. However, he let Sheridan explain in his own words many of the reasons why the United Irishmen wanted to separate from England.

In a letter from 1784, Sheridan explained to his brother that Ireland's "subordinate situation" prevented the formation of political groups like those in England. In Ireland, power was "lodged in a branch of the English government" (the Dublin Castle executive). This meant that members of parliament had little reason to work together for the public good, because they couldn't truly gain power. Without a government that could be held accountable, the nation's interests were often ignored.

Moore believed that this limited political situation in Ireland pushed Lord Edward Fitzgerald, a "Protestant reformer" who wanted a democratic parliament and rights for Catholics, towards the idea of an independent Irish republic. Moore didn't see Fitzgerald as reckless. He argued that if the wind hadn't changed, French help would have arrived with General Hoche at Bantry in December 1796. In his own writings, Moore called his Life and Death of Lord Edward Fitzgerald (1831) a "justification of the men of '98 – the last of our country's Romans."

Moore's History of Ireland, published in four volumes between 1835 and 1846, reads like a long criticism of English rule. It was a huge project (even Karl Marx used it for his notes on Irish history), but it wasn't a big success with critics. Moore admitted that it had some academic weaknesses, partly because he couldn't read original Irish documents.

On Reform and Repeal

Parliamentary Reform

In his journal, Moore admitted that he "agreed with the Tories" about the effects of the first Parliamentary Reform Act (1832). He thought it would "give an opening and impulse to the revolutionary feeling now abroad" in England. He believed that any "temporary satisfaction" it brought would be like the calm before a storm, and that "a downward reform... rolls on fast." However, he welcomed this idea. He told Lord Lansdowne, a Whig leader, that while the results might be "disagreeable" for many of their friends, society had reached a point where wealth was so unevenly distributed that "nothing short of a general routing up can remedy the evil."

Moore predicted that the Tories, despite their initial opposition to reform, would be better at handling this "general routing." He agreed with Benjamin Disraeli (who later wrote the Second Reform Act in 1867) that since the Glorious Revolution, the Tories had taken "a more democratic line." Moore saw this in the careers of Prime Ministers like George Canning and Robert Peel, who were not born into noble families. He felt that "mere commoners by birth could never have attained the same high station among the Whig party."

O'Connell and Repeal

In 1832, Moore turned down a request from Limerick voters to run for the Westminster Parliament as a Repeal candidate. The Repeal movement wanted to undo the Act of Union and bring back an Irish parliament. When Daniel O'Connell saw this as proof of Moore's "lukewarmness in the cause of Ireland," Moore reminded O'Connell of his praise for the "treasonous truths" in Moore's book about Fitzgerald. Moore suggested that these "truths" prevented him from pretending with O'Connell that reversing the Act of Union would be anything less than a real and lasting separation from Great Britain.

Moore believed that relations had been difficult enough after the old Irish Parliament gained its independence from London in 1782. But with a Catholic Parliament in Dublin, which he was sure they would have, the British government would constantly disagree with Ireland. This would happen over issues like the property of the Church of Ireland and absentee landlords, and ongoing problems with trade, foreign agreements, and war.

Moore felt that the "fate of Ireland under English government, whether of Whigs or Tories," seemed so "hopeless" that he was willing to "run the risk of Repeal, even with separation as its too certain consequence." However, like Lord Fitzgerald, Moore believed that independence was only possible if Catholics united with the "Dissenters" (Presbyterians) of the north. He also thought it might require French help again. To "make headway against England," the feelings of Catholics and Dissenters first had to become "nationalized." Moore thought this could be achieved by focusing on the immediate problems caused by the (Anglican and landed) "Irish establishment." Just as he saw O'Connell's strong stance on the Veto as unhelpful, Moore viewed O'Connell's campaign for Repeal as unhelpful or, at best, "premature."

Some of O'Connell's younger supporters, who disagreed with the Repeal Association, shared this view. Young Irelander Charles Gavan Duffy tried to build a "League of North and South" around what Michael Davitt (of the later Land League) called "the program of the Whiteboys and Ribbonmen reduced to moral and constitutional standards"—meaning tenant rights and land reform.

Irish Melodies

Ireland's "National Music"

The Anti-Jacobin Review, a very conservative magazine, saw Moore's Melodies as more than just innocent songs for drawing-rooms. They wrote that "several of them were composed in a very disordered state of society, if not in open rebellion." They believed the songs were "the melancholy ravings of the disappointed rebel." Moore was writing words for what he called "our national music," and his lyrics often showed "an unmistakable intimation of dispossession and loss in the music itself."

Even though Moore had a difficult relationship with O'Connell, his Melodies were used in O'Connell's campaign for Repeal in the early 1840s. The Repeal Association held huge "monster meetings" with over 100,000 people. These meetings were usually followed by public dinners. At these dinners, O'Connell would jump up, spread his arms wide, and shout, "I am not that slave!" Everyone in the room would follow, shouting, "We are not those slaves! We are not those slaves!"

At the biggest meeting of all, held at the Hill of Tara (a traditional site for Irish kings) on August 15, 1843, O'Connell's carriage moved through a crowd, reportedly of a million people. A harpist played Moore's "The Harp that once through Tara's Halls" as he passed.

Later Views and New Appreciation

Some critics felt that Moore's songs had a tone of sadness and defeatism for Ireland. William Hazlitt said that if Moore's Irish Melodies with their "drawing-room, lackadaisical, patriotism" were truly the songs of the Irish nation, then the Irish people deserved to be slaves forever. Hazlitt believed Moore had turned the "wild harp of Erin into a musical snuff box." Later generations of Irish writers seemed to agree with this judgment.

In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce's main character, Stephen Dedalus, passes "the droll statue of the national poet of Ireland" and thinks about its "servile head." Yet, in his father's house, Dedalus is touched when he hears his younger siblings singing Moore's "Oft in the Stilly Night." Despite Joyce sometimes showing disdain for Moore, critic Emer Nolan suggests that Joyce responded to the "element of utopian longing as well as the sentimental nostalgia" in Moore's music. In Finnegans Wake, Joyce refers to almost every one of the Melodies.

While admitting that his own understanding of Irish history was "woven . . . out of Moore's Melodies"," Seamus Heaney wrote in a 1979 tribute that Ireland had taken away Moore's title of national poet. Heaney felt Moore's tone was "too light, too conciliatory, too colonisé" for a nation whose identity was being shaped by James Joyce and W.B. Yeats.

More recently, there has been a new appreciation for Moore's "strategies of disguise, concealment and historical displacement." These strategies were important for an Irish Catholic who often sang songs to wealthy Londoners about Irish suffering and English "bigotry and misrule." The political meaning of the Melodies and their connections to the United Irishmen and the death of Emmet have been discussed in books by Ronan Kelly, Mary Helen Thuente, and Una Hunt.

Eóin MacWhite and Kathleen O'Donnell found that people in Eastern Europe, who were fighting against empires, easily understood the political messages in Moore's works. Greek-Rumanian rebels, Russian Decembrists, and especially Polish thinkers saw Moore's Melodies, Lalla Rookh (which they saw as "a dramatization of Irish patriotism in an Eastern parable"), and Captain Rock as a "cloak of culture and fraternity." All these works were translated into their languages.

Byron's Memoirs

Moore was greatly criticized by people at the time for letting others convince him to destroy Lord Byron's personal writings, called his Memoirs, because they were considered too shocking. However, modern studies suggest that the blame lies elsewhere.

In 1821, with Byron's permission, Moore sold the manuscript that Byron had given him three years earlier to the publisher John Murray. Moore himself admitted that it contained some "very coarse things." When Byron died in 1824, Moore learned that Murray thought the material was unfit for publication. Moore even talked about having a duel over it. But Byron's wife Lady Byron, his half-sister and executor Augusta Leigh, and Moore's rival in Byron's friendship John Cam Hobhouse all convinced him otherwise. In what some called the greatest literary crime in history, in Moore's presence, the family's lawyers tore up all existing copies of the manuscript and burned them in Murray's fireplace.

With help from papers provided by Mary Shelley, Moore gathered what he could. His Letters and Journals of Lord Byron: With Notices of His Life (1830) managed, in the opinion of Macaulay, "to exhibit so much of the character and opinions of his friend, with so little pain to the feelings of the living." Lady Byron still said she was shocked, as did The Times newspaper.

Inspired by Byron, Moore had previously published a collection of songs called Evenings in Greece (1826). He also wrote his only prose novel, The Epicurean (1827), set in 3rd-century Egypt, which was very popular.

1844 Photograph by Henry Fox Talbot

In what might be the earliest known photograph of an Irishman, Moore stands in the center of a calotype (an early type of photograph) taken in April 1844.

Moore is pictured with members of the household of William Henry Fox Talbot, the photographer. Talbot was a pioneer in photography and Moore's neighbor in Wiltshire. It's possible that the lady to the lower right of Moore is his wife, Bessy Moore.

To Moore's left is Henrietta Horatia Maria Fielding (1809–1851), a close friend of the Moores, Talbot's half-sister, and the daughter of Rear-Admiral Charles Fielding.

Moore was very interested in Talbot's early photographic drawings. Talbot, in turn, took pictures of Moore's handwritten poetry. He may have planned to include these in a book called The Pencil of Nature, which was one of the first commercially published books to have photographs.

Death and Legacy

In the late 1840s, as the terrible Great Famine hit Ireland, Moore's health began to fail. He eventually became very ill in December 1849. Thomas Moore died on February 25, 1852. All of his children and most of his friends had passed away before him.

Moore died at 73 years old and was buried in Bromham churchyard, near his cottage home in Wiltshire. His daughter Anastasia, who died at 17, was buried beside him.

Moore had chosen Lord John Russell, a Whig leader, to manage his literary works after his death. Russell, who had just finished his first term as Prime Minister four days before Moore died, faithfully published Moore's papers as his friend wished. The Memoirs, Journal, and Correspondence of Thomas Moore appeared in eight volumes between 1853 and 1856.

Commemoration

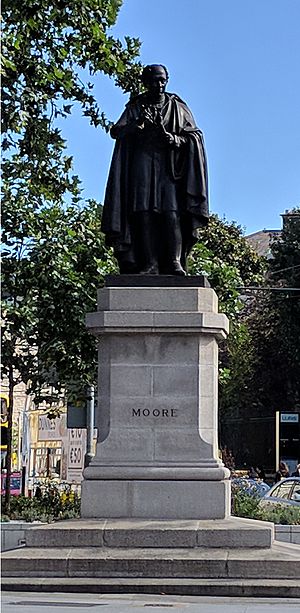

Thomas Moore is often called Ireland's national bard, similar to how Robert Burns is seen in Scotland. Moore is remembered in several places:

- A plaque marks the house where he was born.

- There are busts (sculptures of his head and shoulders) at The Meetings and in Central Park, New York.

- A bronze statue of him stands near Trinity College Dublin.

- A road in Walkinstown, Dublin, is named Thomas Moore Road, part of a series of roads named after famous composers.

Many composers have set Thomas Moore's poems to music, including Ludwig van Beethoven, Robert Schumann, Felix Mendelssohn, and Benjamin Britten. His songs are also mentioned in the works of James Joyce, such as "Silent, O Moyle" in Dubliners and "The Last Rose of Summer".

Oliver Onions quotes Moore's poem "Oft in the Stilly Night" in his 1910 ghost story "The Cigarette Case." This poem is also referenced in Bob Shaw's 1966 science-fiction story "Light of Other Days". The earliest known photograph taken by a woman (Constance Fox Talbot) is a slightly unclear image of a few lines from one of his poems.

List of Works

Prose (Books and Essays)

- A Letter to the Roman Catholics of Dublin (1810)

- The Fudge Family in Paris (1818)

- Memoirs of Captain Rock (1824)

- Memoirs of the Life of Richard Brinsley Sheridan (2 volumes) (1825)

- The Epicurean, a Tale (1827)

- Letters & Journals of Lord Byron, with Notices of his Life (2 volumes) (1830, 1831)

- Life and Death of Lord Edward Fitzgerald (1831)

- Travels of an Irish Gentleman in Search of a Religion (2 volumes) (1833)

- The Fudge Family in England (1835)

- The History of Ireland (volumes 1-4) (1835–1846)

Lyrics and Verse (Poems and Songs)

- Odes of Anacreon (1800)

- Poetical Works of the Late Thomas Little, Esq. (1801)

- The Gypsy Prince (a comic opera, with Michael Kelly, 1801)

- Epistles, Odes and Other Poems (1806)

- A Selection of Irish Melodies, 1 and 2 (1808)

- Corruption and Intolerance, Two Poems (1808)

- The Sceptic: A Philosophical Satire (1809)

- A Selection of Irish Melodies, 3 (1810)

- A Melologue upon National Music (1811)

- M.P., or The Blue Stocking, (a comic opera, with Charles Edward Horn, 1811)

- A Selection of Irish Melodies, 4 (1811)

- Intercepted Letters, or the Two-Penny Post-Bag (1813)

- A Selection of Irish Melodies, 5 (1813)

- A Collection of the Vocal Music of Thomas Moore (1814)

- A Selection of Irish Melodies, 6 (1815)

- Sacred Songs, 1 (1816)

- Lalla Rookh, an Oriental Romance (1817)

- National Airs, 1 (1818)

- A Selection of Irish Melodies, 7 (1818)

- The Works of Thomas Moore (6 volumes) (1819)

- Tom Crib's Memorial to Congress (1819)

- National Airs, 2 (1820)

- Irish Melodies, with a Melologue upon National Music (1820)

- A Selection of Irish Melodies, 8 (1821)

- Irish Melodies (with an Appendix, 1821)

- National Airs, 3 (1822)

- National Airs, 4 (1822)

- The Loves of the Angels, a Poem (1822)

- The Loves of the Angels, an Eastern Romance (5th ed. of Loves of the Angels) (1823)

- Fables for the Holy Alliance, Rhymes on the Road, &c. &c. (1823)

- Sacred Songs, 2 (1824)

- A Selection of Irish Melodies, 9 (1824)

- National Airs, 5 (1826)

- Evenings in Greece, 1 (1826)

- A Set of Glees (circa 1827)

- National Airs, 6 (1827)

- Odes upon Cash, Corn, Catholics, and other Matters (1828)

- Legendary Ballads (1830)

- The Summer Fête. A Poem with Songs (1831)

- Evenings in Greece, 2 (1832)

- Irish Melodies, 10 (with Supplement) (1834)

- Vocal Miscellany, 1 (1834)

- Vocal Miscellany, 2 (1835)

- The poetical works of Thomas Moore, complete in two volumes, Paris, Baudry's European library (1835)

- Alciphron, a Poem (1839)

- The Poetical Works of Thomas Moore, collected by himself (10 volumes) (1840–1841)

- Prose and verse, humorous, satirical and sentimental, by Thomas Moore, with suppressed passages from the memoirs of Lord Byron, chiefly from the author's manuscript and all hitherto inedited and uncollected. With notes and introduction by Richard Herne Shepherd (London: Chatto & Windus, 1878).

|

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Moore para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Moore para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |