Henry Grattan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry Grattan

PC

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of Parliament for Dublin City |

|

| In office 17 December 1806 – 14 April 1820 |

|

| Preceded by | Robert Shaw |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Ellis |

| Member of Parliament for Malton |

|

| In office 4 March 1805 – 17 December 1806 |

|

| Preceded by | Charles Dundas |

| Succeeded by | Charles Wentworth |

| Member of Parliament for Wicklow Borough |

|

| In office 10 August 1800 – 1 January 1801 |

|

| Preceded by | Daniel Grahan |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Member of Parliament for Dublin City |

|

| In office 1 May 1790 – 19 July 1798 |

|

| Preceded by | Travers Hartley |

| Succeeded by | John Claudius Beresford |

| Member of Parliament for Charlemont |

|

| In office 26 October 1775 – 1 May 1790 |

|

| Preceded by | Francis Caulfield |

| Succeeded by | Richard Sheridan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 3 July 1746 Fishamble Street, Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 4 June 1820 (aged 73) Portman Square, London, England |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey, London, England |

| Political party | Patriot (until 1801) Whig (until 1820) |

| Spouses | Henrietta Fitzgerald (m. 1782; d. 1820) |

| Children |

|

| Alma mater | Trinity College Dublin |

| Signature | |

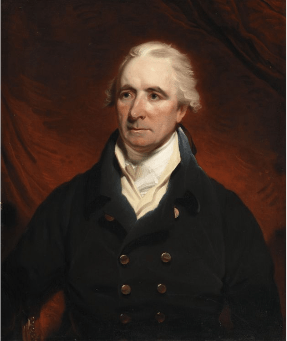

Henry Grattan (born 3 July 1746 – died 4 June 1820) was an important Irish politician and lawyer. He worked hard to gain more freedom for the Irish Parliament in the late 1700s from Britain. He served as a Member of the Irish Parliament (MP) from 1775 to 1801. Later, he became a Member of Parliament (MP) in the British Parliament in London from 1805 to 1820.

Grattan was known as a fantastic speaker. He strongly believed that Ireland should be an independent nation. However, he always wanted Ireland to stay connected to Great Britain through a shared king or queen and similar political traditions. He was against the Act of Union 1800, which joined the Kingdoms of Ireland and Great Britain. Even so, he later served in the united Parliament.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Henry Grattan was born in Fishamble Street, Dublin, Ireland, in 1746. His family was part of the Anglo-Irish elite, who were Protestant. His father, James Grattan, was also an MP for Dublin City. His grandfather, Thomas Marlay, was a well-known judge.

Grattan went to Drogheda Grammar School. Then he became a great student at Trinity College Dublin. There, he developed a love for old classical literature. He was especially interested in the famous speakers from ancient times. Like his friend Henry Flood, Grattan practiced his speaking skills. He studied the works of great writers like Bolingbroke.

In the late 1760s and early 1770s, he lived in London for some years. He also visited France in 1771. While in London, he often watched debates in the British House of Commons. He also met famous people like Oliver Goldsmith at the Grecian Coffee House. It was in London that he became lifelong friends with Robert Day, who later became a judge.

After studying law in London and Dublin, he became a lawyer in 1772. However, he was more interested in politics. He was inspired by Henry Flood. In 1775, he entered the Irish Parliament for Charlemont. He quickly became a leader of the national party. Many believed his speaking skills were the best of his time.

Fighting for Irish Parliament's Freedom

At this time, most Irish people were Catholic. But they were not allowed to take part in public life due to laws called the Penal Laws. These laws were in place from 1691 until the early 1780s. Power was held by the King's representative, called the Viceroy. Also, a small group of Anglo-Irish families, loyal to the Anglican Church of Ireland, owned most of the land.

The politicians of the national party wanted to free the Irish Parliament. They aimed to remove its control by the British Privy Council. An old law called Poynings' Law meant that all new Irish laws had to be approved by the British Privy Council first. The Irish Parliament could only accept or reject a bill, not change it. British laws also made the Irish Parliament completely dependent on Britain. The British Parliament could even make laws directly for Ireland.

Grattan, along with others, became a leader of the Patriot movement. They wanted to change this system.

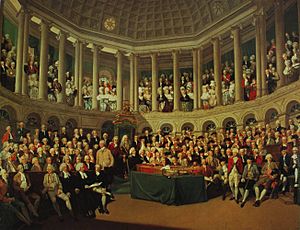

In 1782, calls for Ireland's legislative independence grew stronger. This led the British government to make changes. On 16 April 1782, Grattan walked through crowds of Volunteers outside the Irish Parliament in Dublin. He then proposed a declaration for the independence of the Irish Parliament. He famously said, "I found Ireland on her knees... Ireland is now a nation!"

After about a month of talks, Ireland's demands were met. The Irish people were very grateful to Grattan. Parliament gave him £100,000, but he only accepted half of it. In September of that year, Grattan became a member of the Privy Council of Ireland. He was removed in 1798 but rejoined in 1806.

Grattan's Parliament and Reforms

One of the first actions of Grattan's Parliament was to show its loyalty to the King. They voted to support 20,000 sailors for the Royal Navy. Grattan was loyal to the Crown and wanted Ireland to stay connected to Britain. However, he also wanted to make fair changes to Parliament. Unlike his rival Flood, he supported Catholic Emancipation. This meant giving more rights to Catholics.

It was clear that without reforms, the Irish House of Commons could not truly use its new freedom. Even though it was free from British control, it was still affected by corruption. The British government used this corruption through landowners who controlled small voting areas. The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and his chief secretary were still chosen by British ministers. Their jobs depended on British politics, not Irish.

The Irish House of Commons did not truly represent the Irish people. Most people, whether Catholic or Presbyterian, were excluded. Two-thirds of the members of the House of Commons were chosen by powerful individuals. These individuals often gained titles or money for their support. Grattan pushed for reforms to make the new constitution stable and truly independent.

Grattan also disagreed with protective duties. He supported Pitt's idea in 1785 to create Free Trade between Great Britain and Ireland. However, this plan failed because British merchants were against it. Grattan supported the government for a while after 1782. He voted for laws to deal with Irish disorder. But as time passed, he moved towards the opposition. He pushed for changes to tithes (church taxes) in Ireland. He also supported the Whig party during the regency crisis in 1788. In 1790, Grattan was elected for Dublin City. He held this seat until 1798.

In 1792–93, he helped pass the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1793. This law gave Catholics the right to vote. In 1794, he introduced a reform bill with William Ponsonby. This bill was even milder than Flood's earlier one. Grattan strongly believed that Ireland should be governed by Irish people. But he also thought that too much democracy could lead to chaos. He wanted to allow Catholic men of property to become members of the House of Commons. This was a natural next step after the Relief Act of 1793.

The failure of Grattan's mild proposals led to more extreme ideas. These ideas, influenced by France, were gaining ground in Ireland. The Catholic issue became very important. In 1794, Lord Fitzwilliam, who agreed with Grattan, became Viceroy. People hoped for more Catholic Emancipation. Fitzwilliam asked Grattan to propose a bill for Catholic emancipation, promising British government support. However, Fitzwilliam was recalled in February 1795. This caused great anger and led to more unrest in Ireland. Grattan remained calm and loyal during this time.

The British government, influenced by the King who hated Catholic Emancipation, decided to resist Catholic demands. This quickly pushed Ireland towards rebellion. Grattan warned the government about the lawless state of Ireland in many powerful speeches. But he had only about 40 followers in the Irish House of Commons, and his warnings were ignored. In protest, he left Parliament in May 1797. He also wrote a strong letter to the citizens of Dublin. In it, he said it was "absolutely necessary to reform the state" because people no longer trusted Parliament.

Rebellion and the Act of Union

During this time, many people disliked the Anglican elite in Ireland. People of different faiths began to work together for political goals. Presbyterians in the north, who often supported a republic, joined with some Catholics. They formed the United Irishmen organization. This group promoted revolutionary ideas from France. Some even wanted a French invasion. This led to the Irish Rebellion of 1798. The rebellion, which involved Presbyterians and Catholics in Ulster, also saw outbreaks in places like County Wexford. Grattan was unfairly shown as a rebel leader in cartoons by James Gillray. This was because of his liberal views and his opposition to a political union with Great Britain.

Soon after the rebellion, Pitt's government seriously considered joining the British and Irish parliaments. This idea had been discussed since the 1700s. Grattan strongly spoke out against this plan.

The constitution of Grattan's Parliament did not offer enough security. For example, disagreements over the regency question showed that Ireland and Great Britain might not agree on important imperial matters. Britain was fighting a difficult war with France. The government could not ignore the danger that Ireland's independent constitution offered no protection against armed revolt. The violence during the rebellion ended the growing friendship between Catholics and Presbyterians. Ireland became divided into two opposing groups again.

The strongest opposition to the union came from the Anglican established church and the Orangemen. However, the proposal found support among Catholic clergy and bishops. It was also popular in Cork. This Catholic support came because Pitt encouraged the idea that Catholic emancipation and other benefits would follow the union.

In 1799, the government introduced its bill for union. It was defeated in the Irish House of Commons. Grattan was still retired from Parliament. His popularity had fallen. His ideas for parliamentary reform and Catholic emancipation had become slogans for the United Irishmen. This made the ruling classes strongly dislike him. He was removed from the Privy Council. His portrait was taken down from Trinity College. The Merchant Guild of Dublin removed his name from their lists.

However, the threat to the 1782 constitution quickly brought Grattan back into the hearts of the Irish people. The government used a lot of money and favors to gain support for their policy during the break in Parliament. On 15 January 1800, the Irish Parliament met for its last session. On the same day, Grattan bought a seat for Wicklow Borough. He arrived late, while the debate was happening, and was cheered by the crowd. Grattan was weak when he stood to speak, so he was allowed to speak while sitting. Still, his speech was amazing. He spoke for over two hours, captivating everyone. After long debates, Grattan spoke one last time against the bill on 26 May. He ended with a powerful speech, saying, "I will remain anchored here with fidelity to the fortunes of my country, faithful to her freedom, faithful to her fall." These were Grattan's last words in the Irish Parliament.

The bill to establish the union passed by large majorities. One of Grattan's main reasons for opposing the union was his fear that political leadership in Ireland would no longer be in the hands of the landed gentry. He predicted that Ireland would send "a hundred of the greatest rascals in the kingdom" to the united parliament. Like Flood, Grattan did not favor full democracy. He also thought that moving the center of politics away from Ireland would make the problem of absenteeism (landowners living away from their estates) worse.

In the United Kingdom Parliament

For the next five years, Grattan did not take part in public life. It was not until 1805 that he became a Member of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Malton. He humbly sat on a back bench until Fox brought him forward, saying, "This is no place for the Irish Demosthenes!" (Demosthenes was a famous ancient Greek orator).

Grattan's first speech was on the Catholic question. Everyone agreed that his speech was one of the most brilliant and powerful ever given in Parliament. When Fox and William Grenville came to power in 1806, Grattan was offered a government job. He was then sitting for Dublin City, but he refused the offer. The next year, he showed his strong judgment. He supported a measure to increase the government's power to deal with disorder in Ireland. This made him unpopular in Ireland.

Catholic emancipation, which he continued to support with great energy even in old age, became more complex after 1808. The question arose whether the King should have a veto over the appointment of Roman Catholic bishops. Grattan supported the veto. However, a more radical Catholic party was growing in Ireland under Daniel O'Connell. Grattan's influence slowly decreased. He rarely spoke in Parliament after 1810. A notable exception was in 1815, when he broke from the Whigs and supported the final fight against Napoléon.

His very last speech, in 1819, spoke about the Union he had fought so hard against. It showed Grattan's wise and balanced character. He said his feelings about the Union had not changed. But since the "marriage" had happened, it was now everyone's duty to make it as successful and beneficial as possible.

Death and Lasting Impact

In the summer after his last speech, Grattan traveled from Ireland to Britain. He was in poor health but wanted to bring up the Irish question again. He became very ill. On his deathbed, he spoke kindly of Castlereagh and praised his former rival, Flood. He died at his home in Portman Square, London, on 4 June 1820. He was buried in Westminster Abbey, near the tombs of Pitt and Fox. His statue can be found in St Stephen's Hall in the Palace of Westminster.

Sydney Smith said of Grattan after his death: "No government ever dismayed him. The world could not bribe him. He thought only of Ireland; lived for no other object; dedicated to her his beautiful fancy, his elegant wit, his manly courage, and all the splendour of his astonishing eloquence."

Several places are named in his honor. Grattan Bridge crosses the river Liffey in Dublin. The Henry Grattan Building at Dublin City University houses the faculty of Law and Government. Grattan Square in Dungarvan, County Waterford, was also named after him. This happened in 1855 when Irish Nationalists gained more say in local government.

Family Life

Henry Grattan's father was James Grattan (died 1766), who was an MP for Dublin City. His mother was Mary, daughter of Thomas Marlay.

Grattan married Henrietta Fitzgerald in 1782. She was the daughter of Nicholas Fitzgerald of County Mayo. Henrietta's family history gave Grattan an understanding of past Irish political issues. Her great-grandfather had been forced to move from County Kilkenny to Mayo in 1653.

The Grattans had two sons and two daughters. Their sons were James Grattan and Henry Grattan (junior). Both sons also became Members of Parliament. Their daughter Mary Anne married twice. Their other daughter, Harriet, married the Revd Wake.

Images for kids

Error: no page names specified (help).

See also

In Spanish: Henry Grattan para niños

In Spanish: Henry Grattan para niños

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |