Demosthenes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Demosthenes

|

|

|---|---|

| Δημοσθένης | |

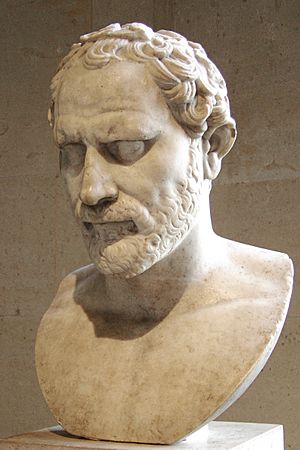

Statue of Demosthenes (Louvre Museum, Paris, France)

|

|

| Born | 384 BC |

| Died | 12 October 322 BC (aged 62) Kalaureia, Greece

|

| Occupation | Speechwriter |

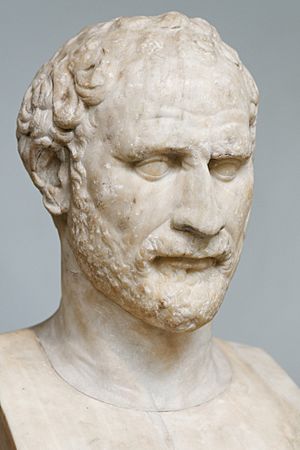

Demosthenes (born 384 BC – died 12 October 322 BC) was a very important Greek leader and speaker in ancient Athens. His speeches show us a lot about the smart thinking and culture of ancient Greece in the 300s BC.

Demosthenes learned how to give powerful speeches by studying other great speakers. He gave his first speeches in court when he was 20 years old. He successfully argued to get back his inheritance from his guardians. For some time, Demosthenes worked as a professional speechwriter, creating speeches for people to use in their court cases. He also worked as a lawyer.

Demosthenes became interested in politics while working as a speechwriter. In 354 BC, he gave his first public political speeches. He spent many years trying to stop the kingdom of Macedon from growing stronger. He loved his city, Athens, and wanted to bring back its power. He tried to get his fellow citizens to stand up against Philip II of Macedon, the king of Macedon. Demosthenes wanted to keep Athens free and create an alliance against Macedon. He tried to stop Philip from taking over other Greek states, but he was not successful.

After Philip died, Demosthenes led Athens in a revolt against the new king of Macedon, Alexander the Great. But his efforts failed, and Macedon reacted strongly. To prevent more revolts, Alexander's general, Antipater, sent people to find Demosthenes. Demosthenes chose to end his own life to avoid being captured by Archias of Thurii, Antipater's trusted man.

Ancient scholars like Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrace listed Demosthenes as one of the ten greatest speakers and speechwriters from Athens. Many famous writers praised him for his powerful and clear speeches.

Demosthenes' Early Life

His Family and Childhood

Demosthenes was born in 384 BC. His father, also named Demosthenes, was a rich sword-maker from Athens. Demosthenes' rival, Aeschines, claimed his mother was from Scythia, but some modern experts disagree. Demosthenes became an orphan when he was seven years old. His father left him a good inheritance, but his legal guardians, Aphobus, Demophon, and Therippides, did not manage his money well.

Demosthenes started learning how to speak well because he wanted to take his guardians to court. He also had a "delicate body" and could not do the usual sports training. The writer Plutarch says that Demosthenes built an underground room to practice speaking. He even shaved half his head so he wouldn't go out in public. Plutarch also wrote that Demosthenes had trouble speaking clearly and would stammer. He overcame this by speaking with pebbles in his mouth and by repeating poems while running. He also practiced speaking in front of a large mirror.

When Demosthenes turned 20 in 366 BC, he asked his guardians to explain what happened to his money. Demosthenes said they had misused his property. His father had left a lot of money, but Demosthenes claimed his guardians left him almost nothing. At 20, Demosthenes sued them to get his inheritance back. He gave five speeches in court for these cases. The courts decided Demosthenes should get back a large amount of money. However, he only managed to get a part of it back.

Demosthenes was married once, but we do not know his wife's name. She was the daughter of a well-known citizen named Heliodorus. Demosthenes also had a daughter who died young before she was married.

How Demosthenes Learned to Speak

Between 366 BC and 364 BC, Demosthenes and his guardians argued a lot but could not agree. During this time, Demosthenes got ready for his court cases and improved his speaking skills. Plutarch tells a story that when Demosthenes was young, a famous speaker named Callistratus noticed his curiosity.

Some historians believe Demosthenes was a student of Isocrates, another famous speaker. Others say he studied with Plato. Plutarch says Demosthenes hired Isaeus as his teacher for speaking. He might have chosen Isaeus because he couldn't pay Isocrates' fee, or because he thought Isaeus' style was better for a strong speaker like himself. Some say Demosthenes paid Isaeus a lot of money to teach him. Demosthenes also admired the historian Thucydides. He even made eight beautiful copies of Thucydides' books in his own handwriting. This shows how much he respected and studied Thucydides.

Improving His Voice

Plutarch wrote that when Demosthenes first spoke to the people, they laughed at his strange way of speaking. But some citizens saw his talent. One time, after the Athenian Assembly refused to listen to him, he went home feeling sad. An actor named Satyrus followed him and talked to him kindly.

As a boy, Demosthenes had a speech problem. Plutarch said he had a weak voice and spoke unclearly, often running out of breath. It is thought that Demosthenes might have had trouble pronouncing the "r" sound, saying "l" instead. Aeschines, his rival, even made fun of him, calling him "Batalus." This name was used for people who spoke quickly and in a messy way. Demosthenes worked very hard to fix his weaknesses and improve how he spoke. He focused on his words, voice, and body movements. A famous story says that when asked the three most important things in speaking, he replied, "Delivery, delivery, and delivery!" These stories show his strong will and determination.

Demosthenes' Career

Working as a Lawyer

To earn a living, Demosthenes became a professional speechwriter, writing speeches for private court cases. He also worked as a lawyer, speaking for others. He was good at handling many types of cases and could adjust his style for different clients, even rich and powerful ones. He might have also taught speaking and brought his students to court. Even though he probably kept writing speeches, he stopped working as a lawyer once he became involved in politics.

| "When you come to court to make decisions, you must remember that you are trusted with the ancient pride of Athens." |

| Demosthenes (On the Crown, 210)—He defended the honor of the courts. |

In Athens, speechwriters were unique. People could present their cases using prepared speeches. However, witnesses and documents were often not trusted, and there was little questioning during trials. Juries were very large, often hundreds of members. Cases often depended on why someone might have acted a certain way, and ideas of fairness were more important than written laws. These conditions made well-crafted speeches very important.

Athenian politicians often accused each other, so there wasn't always a clear line between private and public cases. This meant that working as a speechwriter could lead to a political career. A speechwriter could stay anonymous, which let them serve personal interests. But it also meant they could be accused of doing wrong. For example, Aeschines accused Demosthenes of telling his clients' arguments to their opponents. Plutarch later supported this, saying Demosthenes "was thought to have acted dishonorably."

Starting in Politics

Demosthenes became a full citizen of Athens around 366 BC and quickly showed interest in politics. In 363 and 359 BC, he was a trierarch, meaning he was responsible for equipping and maintaining a warship. In 357 BC, he was one of the first to volunteer as a trierarch, sharing the costs of a ship. In 348 BC, he became a choregos, paying for a theater production.

| "While the ship is safe, whether big or small, that is the time for everyone to show their effort and make sure it is not overturned. But when the sea has taken it, effort is useless." |

| Demosthenes (Third Philippic, 69)—He warned Athenians about future problems if they did not act. |

Between 355 and 351 BC, Demosthenes continued his private law practice while getting more involved in public matters. During this time, he wrote speeches attacking people who tried to remove tax exemptions or supported corruption. These speeches showed his early ideas on foreign policy, like the importance of the navy and alliances.

In 354 BC, Demosthenes gave his first political speech, On the Navy. In it, he suggested changes to how the Athenian fleet was funded. In 352 BC, he spoke For the Megalopolitans and in 351 BC, On the Liberty of the Rhodians. In both speeches, he disagreed with Eubulus, a powerful Athenian leader. Demosthenes wanted Athens to be more active in foreign policy.

Even though his early speeches were not always successful, Demosthenes became an important political figure. He started to lead his own group, separate from Eubulus.

Facing Philip II of Macedon

First Philippic and Olynthiacs (351–349 BC)

Many of Demosthenes' most important speeches were against the growing power of King Philip II of Macedon. Since 357 BC, Athens had been at war with Macedon. In 352 BC, Demosthenes called Philip the worst enemy of Athens. A year later, he warned that Philip was as dangerous as the king of Persia.

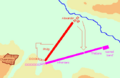

In 352 BC, Athenian troops stopped Philip at Thermopylae. But Philip's victory over the Phocians worried Demosthenes. In 351 BC, Demosthenes felt ready to share his views on the most important foreign policy issue: how Athens should deal with Philip. Demosthenes saw Philip as a threat to the freedom of all Greek cities. In his First Philippic, he told his fellow citizens, "Even if something happens to him, you will soon raise up a second Philip."

The main idea of the First Philippic (351–350 BC) was to get Athens ready for war. Demosthenes called for resistance and said that "for a free people there can be no greater compulsion than shame for their position." He offered a plan for fighting Philip in the north. This plan included creating a quick-response army.

| "We need money, for sure, Athenians, and without money nothing can be done that ought to be done." |

| Demosthenes (First Olynthiac, 20)—He tried to convince his countrymen that changes were needed to pay for military preparations. |

From this time until 341 BC, all of Demosthenes' speeches focused on the fight against Philip. In 349 BC, Philip attacked Olynthus, an ally of Athens. In his three Olynthiacs speeches, Demosthenes criticized Athenians for being inactive and urged them to help Olynthus. He also called Philip a "barbarian." Despite Demosthenes' strong words, the Athenians could not stop Olynthus from falling to Macedon.

The Meidias Incident (348 BC)

In 348 BC, a rich Athenian named Meidias publicly slapped Demosthenes. Demosthenes was a choregos at a religious festival at the time. Meidias was a friend of Eubulus and an old enemy of Demosthenes.

| "Think about it. As soon as this court ends, each of you will walk home, not worried, not looking back, not fearing if you will meet a friend or an enemy. Why? Because you know and trust the State, that no one will seize or insult or strike you." |

| Demosthenes (Against Meidias, 221)—He asked Athenians to protect their laws. |

Demosthenes decided to take Meidias to court and wrote the speech Against Meidias. This speech tells us a lot about Athenian law, especially about hybris (serious assault), which was seen as a crime against both the city and society. He said that a democratic state dies if rich and dishonest men weaken the rule of law. He argued that citizens get power and authority because of "the strength of the laws." Experts disagree on whether Demosthenes actually gave this speech or if he was paid to drop the charges.

Peace of Philocrates (347–345 BC)

In 348 BC, Philip conquered Olynthus and destroyed it. He then conquered the entire region of Chalcidice. After these Macedonian victories, Athens asked for peace with Macedon. Demosthenes was one of those who supported making a deal. In 347 BC, an Athenian group, including Demosthenes, Aeschines, and Philocrates, was sent to Pella to negotiate a peace treaty.

The Athenian Assembly accepted Philip's harsh terms, including giving up their claim to Amphipolis. However, when the Athenian group arrived in Pella to get Philip to swear to the treaty, he was away fighting. Demosthenes wanted the group to travel to find Philip and get him to swear quickly. But the Athenian envoys, including Demosthenes and Aeschines, stayed in Pella until Philip finished his campaign.

Philip swore to the treaty, but he delayed the Athenian envoys' departure. He wanted to secure more Athenian lands before the treaty was final. Demosthenes accused the other envoys of being bribed and helping Philip's plans. Right after the Peace of Philocrates was made, Philip passed through Thermopylae and took over Phocis. Athens did not help the Phocians. Macedon, supported by Thebes and Thessaly, gained control of Phocis' votes in the Amphictyonic League, a Greek religious group. Athens eventually accepted Philip's entry into the League's Council. Demosthenes took a practical approach and advised this in his speech On the Peace.

Second and Third Philippics (344–341 BC)

In 344 BC, Demosthenes traveled to the Peloponnese to try and get cities to leave Macedon's influence. But his efforts mostly failed. Most Peloponnesian cities saw Philip as protecting their freedom. They sent a group to Athens to complain about Demosthenes' actions. In response, Demosthenes gave the Second Philippic, a strong attack against Philip. In 343 BC, Demosthenes gave On the False Embassy against Aeschines, who was accused of serious wrongdoing. However, Aeschines was found not guilty by a small number of votes.

In 343 BC, Macedonian forces were fighting in Epirus, and in 342 BC, Philip fought in Thrace. He also tried to change the Peace of Philocrates with Athens. When the Macedonian army came near the Chersonese (now the Gallipoli Peninsula), an Athenian general named Diopeithes attacked a part of Thrace, making Philip angry. Because of this, the Athenian Assembly met. Demosthenes gave On the Chersonese and convinced the Athenians not to remove Diopeithes. Also in 342 BC, he gave the Third Philippic, considered his best political speech. With all his speaking power, he demanded strong action against Philip. He told them it would be "better to die a thousand times than pay court to Philip." Demosthenes now led Athenian politics and greatly weakened the group that supported Macedon.

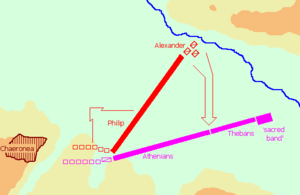

Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC)

In 341 BC, Demosthenes was sent to Byzantium to renew its alliance with Athens. Thanks to Demosthenes' diplomatic skills, Abydos also allied with Athens. These events worried Philip and made him angrier at Demosthenes. The Assembly ignored Philip's complaints about Demosthenes and ended the peace treaty. This was like an official declaration of war. In 339 BC, Philip made his final and most effective move to conquer southern Greece. During a meeting of the Amphictyonic Council, Philip accused the Amfissian Locrians of entering sacred land. Aeschines agreed that Athens should join the Council's meeting to punish the Locrians. However, Demosthenes changed Aeschines' plans, and Athens did not participate. After a first failed attack against the Locrians, the Amphictyonic Council gave command of its forces to Philip. Philip acted quickly, entering Amfissa and defeating the Locrians. After this victory, Philip quickly entered Phocis in 338 BC. He then moved south, took Elateia, and rebuilt the city's defenses.

At the same time, Athens formed an alliance with Euboea, Megara, Achaea, Corinth, Acarnania, and other states. But the most important ally for Athens was Thebes. To get their support, Athens sent Demosthenes to Thebes. Philip also sent a group, but Demosthenes succeeded in getting Thebes to join Athens. The alliance came with a cost: Thebes' control of Boeotia was recognized, Thebes would lead on land, and Athens would pay two-thirds of the war's cost.

While Athens and Thebes prepared for war, Philip tried one last time to make peace, but it failed. After some small fights, Philip led his army against the Athenian and Theban forces near Chaeronea, where he defeated them. Demosthenes fought as a regular soldier. Philip disliked Demosthenes so much that, after his victory, he made fun of the Athenian leader's misfortunes.

Later Political Actions and Death

Facing Alexander the Great

After the battle of Chaeronea, Philip punished Thebes harshly but made peace with Athens on easy terms. Demosthenes encouraged Athens to strengthen its defenses and was chosen to give the funeral speech. In 337 BC, Philip created the League of Corinth, a group of Greek states under his leadership, and returned home. In 336 BC, Philip was killed. The Macedonian army quickly named Alexander III of Macedon, then 20 years old, as the new king. Greek cities like Athens and Thebes saw this as a chance to become fully independent again. Demosthenes celebrated Philip's death and played a big part in Athens' uprising. According to Aeschines, Demosthenes celebrated even though his own daughter had just died. Demosthenes also sent messengers to Attalus, who he thought was against Alexander. However, Alexander quickly moved to Thebes, which surrendered. When Athenians learned Alexander had moved quickly, they panicked and begged for mercy. Alexander warned them but did not punish them.

In 335 BC, Alexander went to fight in the north. While he was away, Demosthenes spread a rumor that Alexander and his army had been killed. Thebans and Athenians rebelled again, with money from Darius III of Persia. Demosthenes was accused of taking money for Athens and misusing it. Alexander reacted immediately and destroyed Thebes. He did not attack Athens, but he demanded that all anti-Macedonian politicians, especially Demosthenes, be sent away. Plutarch says that a special Athenian group, led by Phocion, convinced Alexander to change his mind.

Ancient writers said Demosthenes called Alexander "Margites," a word used for foolish people.

The Speech On the Crown

| "You are revealed in your life and actions, in what you do publicly and what you avoid. When a project approved by the people moves forward, Aeschines is silent. When a bad event is reported, Aeschines appears. He is like an old injury: the moment you are unwell, it becomes active." |

| Demosthenes (On the Crown, 198)—In this speech, Demosthenes strongly attacked Aeschines. |

Even though his plans against Philip and Alexander failed, most Athenians still respected Demosthenes. They shared his feelings and wanted to be independent again. In 336 BC, a speaker named Ctesiphon suggested that Athens honor Demosthenes with a golden crown for his service. This idea became a political issue. In 330 BC, Aeschines accused Ctesiphon of breaking legal rules. In his most famous speech, On the Crown, Demosthenes defended Ctesiphon and strongly attacked those who wanted peace with Macedon. He did not regret his past actions. He said that his goal was always the honor and power of Athens, and he was always loyal to his city. He defeated Aeschines, even though Aeschines' legal arguments against the crowning might have been correct.

The Harpalus Case and Death

In 324 BC, Harpalus, who was in charge of Alexander's treasures, ran away and came to Athens. The Assembly first refused to accept him, following Demosthenes' and Phocion's advice. But Harpalus eventually entered Athens. He was put in prison after Demosthenes and Phocion suggested it. The Assembly also decided to take control of Harpalus' money, which was given to a committee led by Demosthenes. When the committee counted the money, they found only half of what Harpalus said he had. When Harpalus escaped, the Areopagus (a council) investigated. They accused Demosthenes and others of mismanaging money.

Demosthenes was the first to be tried in front of a very large jury. He was found guilty and fined a huge amount of money. Unable to pay, Demosthenes escaped. He returned to Athens nine months later, after Alexander's death. When he came back, his countrymen gave him a very warm welcome. Some historians believe Demosthenes was innocent and that the charges against him were politically motivated. They think he was not paid by Harpalus.

| "For a house, or a ship, or anything like that, its main strength must be in its foundation. And so too in state matters, the principles and foundations must be truth and justice." |

| Demosthenes (Second Olynthiac, 10)—He faced serious accusations but always said he was innocent. |

However, other historians note that many Athenian leaders, including Demosthenes, made money from their political work, often by taking payments from other cities. Demosthenes received large sums for the many laws he proposed. Given this history of such actions in Greek politics, it seems likely that Demosthenes accepted money from Harpalus and was rightly found guilty.

After Alexander's death in 323 BC, Demosthenes again urged Athenians to seek independence from Macedon. This led to the Lamian War. However, Antipater, Alexander's general, stopped all resistance. He demanded that Athens hand over Demosthenes and others. The Assembly had no choice but to agree, sentencing the anti-Macedonian leaders to death. Demosthenes escaped to a safe place on the island of Kalaureia. There, he was found by Archias, Antipater's trusted man. Demosthenes died before he could be captured by taking poison. He pretended he wanted to write a letter to his family. When he felt the poison working, he spoke to Archias, then fell down and died. Years later, Athenians honored Demosthenes with a statue and decided that the state should provide meals to his family.

How Demosthenes is Remembered

His Political Impact

Plutarch praised Demosthenes for being loyal to his beliefs. He said Demosthenes stuck to his political ideas from beginning to end, choosing to die rather than give them up. On the other hand, Polybius, a Greek historian, criticized Demosthenes' policies. He accused Demosthenes of unfairly attacking great men from other cities, calling them traitors. Polybius believed Demosthenes judged everything based on Athens' interests, thinking all Greeks should focus on Athens. According to Polybius, the only thing Athenians got from opposing Philip was defeat at Chaeronea.

| "Two things, Athenians, a good citizen must show: when he has power, he must keep working for noble actions and his country's greatness. And at all times, he must stay loyal. This comes from his own character. His power and influence come from outside reasons. And in me, you will find, this loyalty has always been pure...From the very start, I chose the honest path in public life: I chose to help my country's honor, power, and good name, to make them better, and to succeed or fail with them." |

| Demosthenes (On the Crown, 321–322)—He judged his policies by their ideals, not just their success. |

Some historians praise Demosthenes' love for his country but criticize him for not seeing the bigger picture. They believe he should have understood that Greek states could only survive if they united under Macedon's leadership. So, Demosthenes is sometimes criticized for misjudging events and not seeing Philip's victory as unavoidable. He is also criticized for overestimating Athens' ability to fight Macedon. Athens had lost most of its allies, while Philip had control over Macedon and its wealth.

However, other scholars point out that those who favored peace, like Aeschines, did not have an inspiring vision like Demosthenes. Demosthenes asked Athenians to choose what was right and honorable, even over their own safety. The people preferred Demosthenes' active approach. Even the defeat at Chaeronea was seen as a worthwhile price to try and keep freedom. Historian Arthur Wallace Pickarde said that success might not be the best way to judge people like Demosthenes, who were driven by the ideals of democracy and freedom. Demosthenes tried to bring back Athens' glory and became a "teacher of the people."

The fact that Demosthenes fought at Chaeronea as a regular soldier shows he wasn't a military leader. In his time, politicians and generals were often separate. Demosthenes focused on ideas and policies, not war. Historian George Grote noted that Demosthenes saw the danger from Philip early on. Throughout his career, he showed "earnest patriotism with wise and long-sighted policy." If Athenians and other Greeks had followed his advice, Macedon's power might have been stopped. Grote also said, "it was not Athens only that he sought to defend against Philip, but the whole Hellenic world. In this he towers above the greatest of his predecessors."

His Speaking Skills

In Demosthenes' early court speeches, you can see the influence of other speakers, but his own unique style is already clear. Most of his surviving speeches from private cases show his talent: a strong mind, smart choice of facts, and a confident way of arguing his case. However, at this early stage, his writing was not yet known for its fine details or variety.

According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a Greek historian, Demosthenes perfected the way Attic prose was written. Both Dionysius and Cicero said Demosthenes combined the best parts of different writing styles. He used a normal style most often but could also use older or very elegant styles when needed. He was better than other masters in each style. He is seen as a perfect speaker, skilled in all speaking techniques.

According to scholar Harry Thurston Peck, Demosthenes "aims at no elegance; he seeks no glaring ornaments." He rarely made soft, emotional appeals. Peck says the secret of his power was that his political beliefs were deeply connected to his spirit. George A. Kennedy believes his political speeches were "the artistic exposition of reasoned views."

Demosthenes was good at mixing short, sudden sentences with longer ones. His style matched his strong feelings. His language was simple and natural, never fake. According to Jebb, Demosthenes was a true artist who controlled his art. Aeschines, his rival, criticized his intensity, calling his ideas "absurd." Dionysius said Demosthenes' only flaw was a lack of humor. Cicero, who admired Demosthenes, sometimes felt Demosthenes "nods" or failed to fully satisfy him. The main criticism of Demosthenes' speaking was that he often did not like to speak without preparing first. However, he prepared all his speeches very carefully, so his arguments were well-thought-out. He was also known for his sharp wit.

Besides his style, Cicero also admired Demosthenes' good rhythm and how he organized his speeches. Cicero believed Demosthenes thought "delivery" (gestures, voice) was more important than style. Even though he didn't have Aeschines' charming voice or Demades' skill at speaking without preparation, he used his body effectively to make his words stronger. This helped him present his ideas powerfully. However, not everyone in ancient times liked his delivery. Some people made fun of his "theatricality."

Demosthenes used different ways to make himself believable. When speaking to the Assembly, he had to show himself as a wise leader to be convincing. One method he used was foresight. He urged his audience to imagine being defeated and to prepare. He appealed to their emotions by talking about patriotism and the terrible things that would happen if Athens was taken over by Philip. He was good at showing his past achievements to build trust. He would also cleverly tell his audience they were wrong for not listening before, but they could make up for it by listening and acting with him now.

Demosthenes changed his style for each audience. He was proud of using simple, effective language instead of fancy words. He carefully arranged his sentences to make complex ideas easy to follow. He often repeated things to make them stick in the audience's minds. He also used speed and pauses to create excitement when presenting important parts of his speech. One of his best skills was finding a balance: his speeches were complex enough not to sound too simple, but the most important parts were clear and easy to understand.

Demosthenes' Lasting Influence

Demosthenes is widely thought to be one of the greatest speakers of all time. His fame has lasted through the centuries. Writers and scholars in Rome admired his speeches. Juvenal called him "a large and overflowing fountain of genius." He inspired Cicero's speeches against Mark Antony, which were also called the Philippics. Professor Cecil Wooten says Cicero ended his career trying to be like Demosthenes in politics.

During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, Demosthenes was known for his speaking skills. He was read more than almost any other ancient speaker, with only Cicero being a real rival. French writer Guillaume du Vair praised his speeches for their clever structure and elegant style. John Jewel, a bishop, and Jacques Amyot, a French writer, saw Demosthenes as a great or even the "supreme" speaker. For Thomas Wilson, who first translated Demosthenes' speeches into English, Demosthenes was not just a good speaker but also a wise leader, "a source of wisdom."

In modern history, speakers like Henry Clay copied Demosthenes' methods. His ideas and principles have influenced important politicians and movements today. He inspired the writers of The Federalist Papers (essays supporting the U.S. Constitution) and major speakers of the French Revolution. French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau admired Demosthenes and wrote a book about him. Friedrich Nietzsche, a philosopher, often wrote his sentences in a style similar to Demosthenes, whose writing he admired.

His Works and How They Survived

The "publication" and sharing of written speeches was common in Athens by the late 300s BC. Demosthenes was one of the Athenian politicians who helped this trend, publishing many or all of his speeches. After his death, copies of his speeches were kept in Athens and in the Library of Alexandria.

The texts from Alexandria became part of the classic Greek writings that were saved and studied by scholars. From then until the 300s AD, many copies of Demosthenes' speeches were made. They were in a good position to survive the difficult period from the 500s to the 800s AD. Today, sixty-one speeches are believed to be by Demosthenes (though some might be by others). Friedrich Blass, a German scholar, thinks nine more speeches were recorded but are now lost. Modern versions of these speeches are based on four old handwritten copies from the 900s and 1000s AD.

Some speeches in the "Demosthenic collection" are known to have been written by other authors, but scholars disagree on which ones. The speeches attributed to Demosthenes are often put into three groups:

- Symbouleutic or political: These speeches discuss what should be done in the future. Sixteen such speeches are in the collection.

- Dicanic or judicial: These speeches judge past actions. Only about ten of these are cases Demosthenes was personally involved in; the rest were written for other speakers.

- Epideictic or display: These speeches give praise or blame, often at public events. Only two are in the collection. One funeral speech is considered "poor," and the other is probably not by him.

Besides the speeches, there are fifty-six prologues (speech openings). They were collected for the Library of Alexandria by Callimachus, who thought they were real. Modern scholars are divided on whether they are truly by Demosthenes. Finally, six letters also exist under Demosthenes' name, and their true author is also debated.

Later Honors

The Demosthenian Literary Society, founded in 1803 at the University of Georgia, was named in honor of Demosthenes. In 1936, an American botanist named Albert Charles Smith named a group of South American shrubs Demosthenesia in honor of Demosthenes.

Images for kids

-

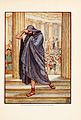

Demosthenes Practising Oratory by Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouy (1842–1923). Demosthenes used to study in an underground room he constructed himself. He also used to talk with pebbles in his mouth and recited verses while running. To strengthen his voice, he spoke on the seashore over the roar of the waves.

See also

In Spanish: Demóstenes para niños

In Spanish: Demóstenes para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |