Duncan Campbell Scott facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

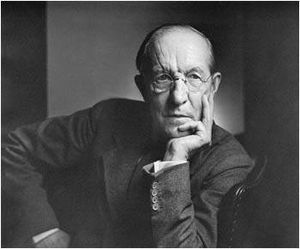

Duncan Campbell Scott

CMG FRSC

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | August 2, 1862 Ottawa, United Province of Canada |

| Died | December 19, 1947 (aged 85) Ottawa, Canada |

| Occupation | Civil servant |

| Citizenship | British subject |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Literary movement | Confederation Poets |

| Notable awards | CMG, Lorne Pierce Medal, FRSC |

| Spouse | Belle Botsford, Elise Aylen |

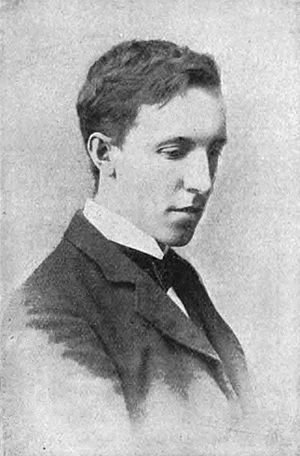

Duncan Campbell Scott CMG FRSC (born August 2, 1862 – died December 19, 1947) was a Canadian government worker and a talented poet and writer. He is known as one of Canada's Confederation Poets, alongside famous writers like Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carman, and Archibald Lampman.

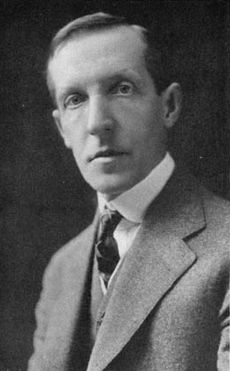

Scott spent his career working for the government. From 1913 to 1932, he was the deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs. This was a very important role in the government's dealings with Indigenous peoples.

Contents

Life and Early Career

Duncan Campbell Scott was born in Ottawa, Ontario. His father, William Scott, was a Methodist preacher. Duncan went to Stanstead Wesleyan College. From a young age, he was a skilled pianist.

Scott initially wanted to become a doctor. However, his family's money situation was difficult. So, in 1879, he joined the federal civil service, which meant working for the government.

His father, William Scott, knew important people, including the Prime Minister, Sir John A. Macdonald. Macdonald met with Duncan and offered him a temporary job as a copying clerk in the Indian Branch of the Department of the Interior. This was the start of Scott's long career in government.

Scott worked in the same government department his entire career. He rose through the ranks to become the deputy superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1913. This was the highest non-elected position in his department. He stayed in this role until he retired in 1932.

Duncan Campbell Scott lived in a new house on 108 Lisgar St. in Ottawa for the rest of his life. His father also later worked in Indian Affairs.

Friendship and Early Poetry

In 1883, Scott met Archibald Lampman, another government worker. They became instant friends. Scott introduced Lampman to wilderness camping trips, which Lampman loved. Lampman's dedication to poetry inspired Scott to start writing his own poems.

By the late 1880s, Scott's poems were appearing in Scribner's, a respected American magazine. In 1889, his poems "At the Cedars" and "Ottawa" were part of an important early collection called Songs of the Great Dominion.

Scott and Lampman both loved poetry and the Canadian wilderness. In the 1890s, they often went on canoe trips together in the area north of Ottawa.

From 1892 to 1893, Scott, Lampman, and William Wilfred Campbell wrote a literary column for the Toronto Globe newspaper. They called it "At the Mermaid Inn." Scott chose the name to remind people of The Mermaid Inn Tavern in old London. Famous writers like Ben Jonson used to meet there.

Published Works

In 1893, Scott published his first book of poetry, The Magic House and Other Poems. He would go on to publish seven more poetry books, including:

- Labor and the Angel (1898)

- New World Lyrics and Ballads (1905)

- Via Borealis (1906)

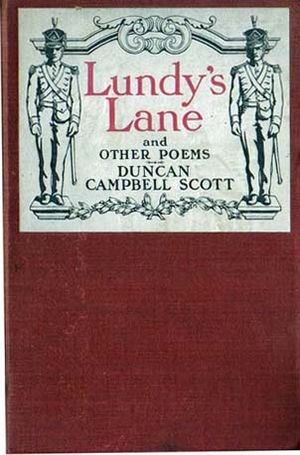

- Lundy's Lane and Other Poems (1916)

- Beauty and Life (1921)

- The Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott (1926)

- The Green Cloister (1935)

In 1894, Scott married Belle Botsford, who was a concert violinist. They had one child, Elizabeth, who sadly died at age 12.

Scott also wrote short stories. His first collection, In the Village of Viger, came out in 1896. It featured gentle stories about French Canadian life. Later collections included The Witching of Elspie (1923) and The Circle of Affection (1947). He also wrote a novel, The Untitled Novel, which was published after his death in 1979.

After Archibald Lampman died in 1899, Scott helped publish several editions of Lampman's poetry.

Scott also helped start the Ottawa Little Theatre and the Dominion Drama Festival. In 1923, his one-act play, Pierre, was performed by the Little Theatre.

His first wife, Belle, passed away in 1929. In 1931, Scott married Elise Aylen, who was also a poet. After he retired in 1932, the couple traveled a lot in Europe, Canada, and the United States during the 1930s and 1940s.

Duncan Campbell Scott died in December 1947 in Ottawa at 85 years old. He is buried in Ottawa's Beechwood Cemetery.

Honours and Awards

Scott received many honours for his writing during his lifetime and after. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada in 1899 and was its president from 1921 to 1922. In 1927, the Society gave him the Lorne Pierce Medal for his important contributions to Canadian literature.

In 1934, he was made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George. He also received honorary degrees from the University of Toronto (in 1922) and Queen's University (in 1939). In 1948, the year after he died, he was named a Person of National Historic Significance in Canada.

Poetry and Themes

Duncan Campbell Scott's writing is highly regarded. His poems have been included in almost all major collections of Canadian poetry since 1900.

Scottish literary critic William Archer wrote about Scott in 1901. He said Scott was a "poet of climate and atmosphere." Archer noted that Scott used "clear, pure, transparent colours" in his writing. He also mentioned Scott's "philosophic and also a romantic strain." Archer believed Scott's work was "careful and highly finished."

The Government of Canada's biography of Scott states that his best work describes the Canadian wilderness and Indigenous peoples. Even though these poems are a small part of his writing, they helped build his literary fame. In these poems, you can feel Scott's mixed feelings. He was a government administrator who supported a policy for Indigenous peoples to adopt European ways. But as a poet, he felt sad about how European civilization was changing the Indigenous way of life.

Desmond Pacey, a literary critic, said that Scott's first book, The Magic House and Other Poems, had "not a really bad poem" and "a number of extremely good ones." One well-known poem from this collection is "At the Cedars." It's a dramatic story about a young couple who die during a log-jam on the Ottawa River.

His next book, Labour and the Angel, showed Scott's willingness to try new poem structures. Notable poems included "The Cup" and the sonnet "The Onondaga Madonna." "The Piper of Arll" was also very memorable. John Masefield, who later became the British Poet Laureate, read "The Piper of Arll" as a teenager. Years later, he wrote to Scott, saying the poem "impressed me deeply, and set me on fire."

New World Lyrics and Ballads (1905) showed Scott's unique voice. His dramatic writing about the wilderness and the lives of people there became more clear. This book included "On the Way to the Mission" and "[The Forsaken]." These are two of Scott's most famous "Indian poems."

Lundy's Lane and Other Poems (1916) included the title poem, which won Scott a prize for the best poem about Canadian history. Other important poems in this book are "A Love Song," "The Height of Land," and "Lines Written in Memory of Edmund Morris." One anthologist called the last poem "so original, tender and beautiful that it is destined to live among the best in Canadian literature."

Scott considered Beauty and Life (1921) his favorite poetry book. It contained many different types of poems he enjoyed writing. These ranged from the moving war poem "To a Canadian Aviator Who Died For His Country in France" to the mysterious "A Vision."

The Green Cloister, published after Scott retired, is like a travel journal. It describes places he visited in Europe with his second wife, Elise. It also includes two dramatic "Indian poems" with Canadian settings.

The Circle of Affection (1947) contains 26 poems Scott wrote after The Green Cloister. It also has some prose pieces. The poem "At Delos" suggests he was aware of his own mortality. He died that same year.

-

-

- There is no grieving in the world

- As beauty fades throughout the years:

- The pilgrim with the weary heart

- Brings to the grave his tears.

- There is no grieving in the world

-

Work in Indian Affairs

Before becoming the head of the Department of Indian Affairs, Scott was one of the Treaty Commissioners. In 1905, he helped negotiate Treaty No. 9 in Northern Ontario.

Scott's most significant impact on Canadian history, besides his poetry, was as the top government worker in the Department of Indian Affairs. He held this role from 1913 to 1932.

Even before Canada became a country, the government had a policy to encourage First Nations people to adopt the ways of European Canadians. This was called the Gradual Civilization Act of 1857. One writer about Scott explained his view:

The Canadian government's Indian policy had already been set before Scott was in a position to influence it, but he never saw any reason to question its assumption that the 'red' man ought to become just like the 'white' man. Shortly after he became Deputy Superintendent, he wrote approvingly: 'The happiest future for the Indian race is absorption into the general population, and this is the object and policy of our government.'... Assimilation, so the reasoning went, would solve the 'Indian problem,' and wrenching children away from their parents to 'civilize' them in residential schools until they were eighteen was believed to be a sure way of achieving the government's goal. Scott ... would later pat himself on the back: 'I was never unsympathetic to aboriginal ideals, but there was the law which I did not originate and which I never tried to amend in the direction of severity.'

Scott himself wrote about this goal:

I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone… Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill.

In 1910, a report by Peter Bryce warned the department about serious tuberculosis outbreaks in residential schools. Scott did not support changes to the policy based on Bryce's recommendations. He stated that the number of diseases and deaths in the schools "does not justify a change in the policy of this Department, which is geared towards a final solution of our Indian Problem."

In 1920, under Scott's leadership, the Indian Act was changed. It made it mandatory for all Indigenous children aged seven to fifteen to attend school. Attending a residential school became compulsory if it was the only type of school available. This meant Indigenous children were sometimes forced to leave their homes and families. Scott believed that removing children from their homes would help them adopt European Canadian culture and economy faster.

However, in 1901, most Indigenous schools (226 out of 290) were day schools. By 1961, there were many more day schools (377) than residential schools (56).

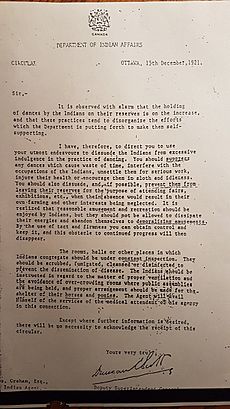

In December 1921, Scott wrote a letter to his staff about Indigenous customs. He expressed concern that dances on reserves were increasing. He believed these practices interfered with efforts to make Indigenous people self-supporting. Scott directed his agents to "use your utmost endeavours to dissuade the Indians from excessive indulgence in the practice of dancing." He added that agents should use tact to "obtain control and keep it" and prevent Indigenous people from attending "fairs, exhibitions etc." He believed that while some amusement was fine, Indigenous people "should not be allowed to dissipate their energies and abandon themselves to demoralizing amusements." This letter has been seen in the 21st century as showing Scott's negative views toward Indigenous customs.

In 2008, when problems in the residential schools were being investigated, CBC reported that about 150,000 Indigenous children were forced to attend these schools. It's important to note that many children attended day schools in their communities. While the residential school system faced much criticism for poor conditions and abuse, most children were educated in day schools. The goal of changing Indigenous culture was present in all schools.

When Scott retired, his policy of encouraging Indigenous people to adopt European Canadian ways was widely accepted at the time. He was praised for his management. Scott noted that school enrollment and attendance increased. The number of First Nations children in any school rose from 11,303 in 1912 to 17,163 in 1932. Residential school enrollment also increased. Scott believed this was partly due to the law making attendance compulsory. He also thought First Nations people had a more positive view of education.

However, Scott's efforts to achieve assimilation through residential schools did not fully succeed. Many former students kept their language and culture as adults. They also often refused full Canadian citizenship when it was offered. Also, only a small number of students went beyond elementary grades. This meant they often lacked skills for employment.

In 2015, the plaque at his grave in Ottawa's Beechwood cemetery was updated. It now states:

As Deputy Superintendent, Scott oversaw the assimilationist Indian Residential School system for Aboriginal children, stating his goal was 'to get rid of the Indian problem'" ... " In its 2015 report, Canada's Truth and Reconciliation Commission said that the Indian Residential School system amounted to cultural genocide.

Reputation as an Assimilationist

In 2003, Scott's work in Indian Affairs was criticized by writers Neu and Therrien. They described him as a complex person:

[Scott] took a romantic interest in Native traditions, he was after all a poet of some repute (a member of the Royal Society of Canada), as well as being an accountant and a bureaucrat. He was three people rolled into one confusing and perverse soul. The poet romanticized the whole 'noble savage' theme, the bureaucrat lamented our inability to become civilized, the accountant refused to provide funds for the so-called civilization process. In other words, he disdained all 'living' Natives but "extolled the freedom of the savages".

According to Encyclopædia Britannica, Scott is best known today not for his writing, but for supporting the policy of assimilation for Canada's First Nations peoples. In 2007, a panel of experts for The Beaver magazine named Scott one of the "Worst Canadians" in their poll.

In his 2013 book, Conversations with a Dead Man: The Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott, writer Mark Abley explored Scott's complex character. Abley did not defend Scott's government work. However, he showed that Scott was more than just a simple villain.

See also

- Canadian literature

- Canadian poetry

- List of Canadian poets

Images for kids

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |