Gradual Civilization Act facts for kids

The Act to Encourage the Gradual Civilization of Indian Tribes in this Province, and to Amend the Laws Relating to Indians is often called the Gradual Civilization Act. It was a law passed in 1857 by the Parliament of the Province of Canada. This Act created a way for recognized Indigenous men to become "enfranchised". This meant they would lose their legal ‘Indian status’ and become regular British subjects.

To apply, men had to speak English or French. A group of non-Indigenous people would decide if they were approved. If approved, they would get land and the right to vote. This Act aimed to make Indigenous people more like the European settlers.

The Act built on older British laws about Indigenous rights. These laws started with the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which protected Indigenous lands. By the 1830s, Britain wanted to 'civilize' Indigenous people in Canada. They placed them on protected reserves to teach them European skills, values, and religion. The 1857 Act wanted to fully blend Indigenous people into settler society through enfranchisement.

The Act's policies took away some power from Indigenous tribal councils. These councils usually managed their own affairs. Because of this, many councils fought against the Act. They wanted it to be cancelled, but they were not successful. In the end, only one Indigenous person became enfranchised under this Act.

The Gradual Civilization Act was later updated by the Gradual Enfranchisement Act in 1869. Ideas from both these Acts were put into the Indian Act of 1876. The Indian Act still guides the relationship between the Canadian government and First Nations today, though it has changed many times.

How It Started

Early Relations Between Britain and Indigenous Peoples

Britain's first policies about Indigenous lands and rights began in the mid-1700s. Britain needed Indigenous groups as military allies against France in North America. In 1753, the Mohawk declared their alliance with Britain, called the Covenant Chain, broken. This was because colonists were taking Indigenous land. Losing this ally was a big problem for Britain, especially when the French and Indian War started in 1754.

When colonial governments could not fix things with the Iroquois Confederacy, Britain took over. In 1755, they created the British Indian Department. This department had leaders who protected Indigenous lands. They also controlled trade between Indigenous people and colonists, who often cheated them. The department gave gifts to tribes to gain their support. These actions convinced the Iroquois to rejoin Britain in the French and Indian War. Britain won the war and gained most of France's land in North America through the Treaty of Paris (1763).

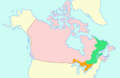

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 made these protective policies official British law. It set aside land west of the Appalachian Mountains as an Indigenous reserve. It also created a way for the government to buy Indigenous land through treaty agreements. The Royal Proclamation created a "nation-to-nation" relationship between Britain and its Indigenous allies. This relationship was based on protection and working together. Indigenous tribes stayed loyal during the American Revolutionary War. But when Britain lost in 1781, they lost their traditional lands. Britain then gave them new land in its remaining North American territories, called the British Canadas.

Creating Indian Reserves

After 1815, Britain's view of Indigenous peoples changed. They started to focus on 'civilization' in addition to protection. Protestant groups in the colonies and Britain believed the government should 'civilize' Indigenous people. This meant converting them to Christianity and teaching them European ways of life. This led to the creation of Indian reserves in Upper Canada and Lower Canada in 1830. On these reserves, Indigenous people were taught farming and other skills. They also received English education and Christian teachings from missionaries.

The Act for the Protection of the Indians in Upper Canada (1839) said that reserves were Crown lands. In 1850, more protective laws were passed in both Upper and Lower Canada. Indigenous people on reserves did not have to pay taxes. Colonists were not allowed to trespass on Indigenous lands or take them if debts were unpaid. In Lower Canada, a new law defined ‘Indian status’ for the first time.

Why Enfranchisement Was Important to Politicians

By 1857, Canadian politicians and Indian Department officials were getting "impatient." They felt that Indigenous people on reserves were not changing fast enough. The colonial government also faced pressure from Britain to lower the costs of managing Indigenous affairs. Two important studies, the 1844 Bagot Commission and the 1856 Pennefather Commission, suggested that owning private property and becoming enfranchised would motivate Indigenous people. They believed this would help Indigenous people become self-sufficient and 'civilized' members of colonial society.

Many experts agree that these studies changed British policy. The goal shifted from protecting Indigenous people as a separate group to fully blending them into settler society. This goal became law with the Gradual Civilization Act in 1857. It created a legal way for Indigenous people on reserves to become enfranchised and receive their own piece of land.

What the Act Did

The Act's introduction stated its goal: to help Indigenous people become 'civilized' and remove legal differences between them and other Canadian subjects. It also aimed to make it easier for individuals to own property and gain rights.

'Indian Status'

Sections 1 and 2 of the Act defined who was an ‘Indian’. It also said that this status would be removed upon enfranchisement. To be a ‘status Indian’, a person had to have Indigenous ancestors or be married to someone with Indigenous ancestry. They also had to be a member of a recognized Indian band and live on that band's land. An 'enfranchised Indian' would lose this status and the special legal rights that came with it. For example, the Act said that enfranchised Indigenous people would no longer be protected from debt to non-Indigenous people.

How to Become Enfranchised

Section 3 of the Act explained how Indigenous men could apply for enfranchisement. Only men over 21 could apply. A committee would then examine them. This committee included an Indian Department official, a missionary, and another non-Indigenous person. The committee was told to approve applicants who could read and write English or French. They also had to be "sufficiently" educated, "of good moral character," and debt-free. If approved, an Indigenous man would be officially enfranchised by the government.

Section 4 described a different process for Indigenous men (aged 21 to 40) who could not read or write but spoke English or French. If the committee thought such a man was "sober and industrious," "intelligent enough," and debt-free, he would be on probation for three years. If he behaved well during this time, he could then be officially enfranchised.

An enfranchised Indigenous man had to choose a last name, which the committee had to approve. The Superintendent General of Indian Affairs would then give him up to 50 acres (20 hectares) of land from his band's reserve. He would also receive a lump sum of money. This money was equal to his share of the yearly payments and income received by the band. This land and money became his own property. However, he would no longer be a member of the band. This meant he lost any future claim to its lands or money.

How the Act Treated Women Differently

Several parts of the Act treated Indigenous women differently from men regarding enfranchisement. Women were not allowed to apply on their own. Instead, if a woman's husband became enfranchised, she would automatically become enfranchised with him. She could only regain her band membership if she remarried a status Indian.

An enfranchised woman would not receive any reserve land. If her husband died, she would only get his land if he had no children. Enfranchised women were allowed their share of band money, but unlike men, they did not get it all at once. A woman's share would be "held in trust" by the Indian Department. The department would then pay her yearly interest.

What Happened Because of the Act

Impact on Indigenous Rights

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 said that Indigenous tribes controlled their own lands. Their land could only be acquired through formal treaty agreements. However, the Gradual Civilization Act allowed the Indian Department to give reserve lands to enfranchised Indigenous people. This could happen without the consent of the tribal council. This went against the idea of tribal self-governance that had been in place since 1763.

The Act also continued a trend started in 1850 in Lower Canada. The colonial government began deciding who counted as an Indigenous person. The Act's legal definition of a ‘status Indian’ replaced the traditional way Indigenous communities identified their own members. The Act also created a way for the government to reduce the number of people with this status. Enfranchisement meant the loss of ‘Indian status’ for the man who applied, his wife, and all their future children.

The Act treated Indigenous women unfairly. They had fewer rights than men. Women had no control over their own society and culture. If their husband was enfranchised, a woman automatically lost her ‘Indian status’. This showed how the colonial government viewed women as "dependents."

Who Applied for Enfranchisement

Tribal governments strongly resisted the Act. Because of this, very few Indigenous people chose to become enfranchised. In the Grand River Reserve of the Six Nations Confederacy, three Mohawk men applied in the first year. A committee approved only one of them, Elias Hill. He passed a "civilization test" by reciting the catechism and the names of the world's seven continents. This test was made up on the spot. Hill was the only Indigenous person enfranchised under the Act before it was combined into the Indian Act of 1876. The Confederacy Council refused to accept his enfranchisement for 30 years. They eventually gave him cash instead of the reserve lands the Act promised.

How It Influenced Later Laws

The 1857 Act set important legal and political examples for later laws. These laws were passed by the government of the new Dominion of Canada. Experts say the Act changed the main idea behind how the government treated Indigenous people. The goal of 'civilization' now meant fully absorbing their lands and peoples into colonial society. The Act made enfranchisement the way to achieve this "eradication." This led to more enfranchisement policies in the Gradual Enfranchisement Act of 1869 and the Indian Act of 1876.

Government officials and missionaries blamed the Act's failure (only one successful enfranchisement) on the resistance of tribal councils. They started a campaign against Indigenous self-governance in the 1860s. They argued that tribal leaders were "the major block on the road to civilization." The Gradual Civilization Act already allowed the colonial government to interfere with Indigenous control over their lands. It allowed individual pieces of reserve land to be given to enfranchised Indigenous people. The Gradual Enfranchisement Act went further. It gave the Canadian government the power to reject any legal decisions made by tribal councils. The later Indian Act gave complete control of Indigenous governance to the Parliament of Canada.

See also

- Cultural assimilation of Native Americans

- Indian Act

- Macaulayism

- Code de l’Indigénat – a set of French colonial laws with a similar goal

- Aboriginal Protection Act of Australia, 1869

Images for kids

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |