Gustav Holst facts for kids

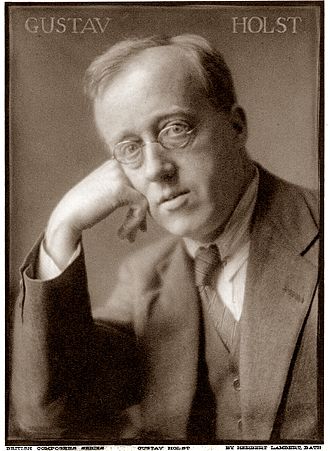

Gustav Theodore Holst (born Gustavus Theodore von Holst; September 21, 1874 – May 25, 1934) was an English composer, music arranger, and teacher. He is most famous for his amazing orchestral piece, The Planets. Holst wrote many other musical works in different styles, but none became as popular as The Planets. His unique musical style was shaped by many things, especially the music of Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss when he was younger. Later, he was inspired by the English folk music revival and modern composers like Maurice Ravel. This helped Holst create his very own special sound.

Holst came from a family of musicians, going back three generations. It was clear from a young age that he would also become a musician. He wanted to be a pianist, but a problem with his right arm (called neuritis) stopped him. Even though his father had doubts, Holst decided to become a composer. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Charles Villiers Stanford. Since he couldn't make enough money just from composing, he played the trombone professionally. Later, he became a teacher, and his friend Ralph Vaughan Williams said he was a great one! He helped build a strong music program at Morley College and was a pioneer in music education for girls at St Paul's Girls' School. He also started music festivals called Whitsun festivals, which continued for the rest of his life.

Holst's music was played often in the early 1900s. But he only became truly famous after The Planets became a huge success around the world after World War I. Holst was a shy person and didn't like being famous. He preferred to quietly compose and teach. In his later years, some people found his music a bit too serious, and his popularity faded. However, he greatly influenced younger English composers like Edmund Rubbra, Michael Tippett, and Benjamin Britten. Besides The Planets and a few other pieces, his music was mostly forgotten until the 1980s, when many of his works were recorded.

Contents

Gustav Holst's Life and Music

Early Life and Family

Family Background

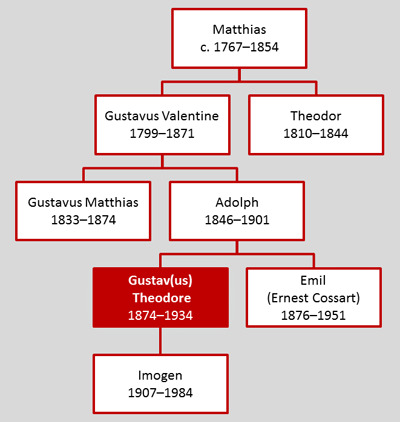

Gustav Holst was born in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England. He was the older of two children. His father, Adolph von Holst, was a professional musician. His mother, Clara Cox, came from a British family. The Holst family had roots in Sweden, Latvia, and Germany, and there had been at least one professional musician in their family for three generations before Gustav.

One of Holst's great-grandfathers, Matthias Holst, was German and born in Latvia. He worked as a composer and harp teacher for the Russian royal family. Matthias's son, Gustavus, moved to England as a child in 1802. He was a composer of light music and a well-known harp teacher. He added "von" to the family name to sound more important and attract more students.

Holst's father, Adolph von Holst, was an organist and choirmaster at All Saints' Church, Cheltenham. He also taught music and gave piano concerts. Gustav's mother, Clara, was a talented singer and pianist. Gustav had a younger brother, Emil Gottfried, who became a successful actor known as Ernest Cossart. Clara died in 1882, and the family moved. Adolph's sister, Nina, helped raise the boys. Gustav was very grateful to her and dedicated some of his early music to her. In 1885, Adolph married Mary Thorley Stone, another one of his students. They had two more sons, Matthias and Evelyn. Mary was interested in theosophy (a spiritual philosophy) and not very involved in family life. All four of Adolph's sons were somewhat neglected. Gustav, especially, was "miserable and scared" because his weak eyesight and chest problems were not properly cared for.

Childhood and Youth

Holst learned to play the piano and violin. He liked the piano but disliked the violin. When he was twelve, his father suggested he play the trombone, hoping it would help his asthma. Holst went to Cheltenham Grammar School from 1886 to 1891. He started composing around 1886. He was inspired by Macaulay's poem Horatius and began a big piece for choir and orchestra, but he didn't finish it. His early music included piano pieces, organ music, songs, and a symphony (from 1892). At this time, he was mainly influenced by Mendelssohn, Chopin, Grieg, and especially Sullivan.

Adolph wanted his son to be a pianist, not a composer. Holst was very sensitive and often unhappy. His eyes were weak, but no one realized he needed glasses. Holst's health greatly affected his musical future. He was never strong, and besides his asthma and poor eyesight, he suffered from neuritis, which made playing the piano difficult. He described his affected arm as "like a jelly overcharged with electricity."

After school in 1891, Holst spent four months in Oxford studying music theory with George Frederick Sims. When he returned, at age seventeen, he got his first job as an organist and choirmaster in Wyck Rissington, Gloucestershire. This job also included leading the Bourton-on-the-Water Choral Society. This experience helped him improve his conducting skills. In November 1891, Holst gave his first public performance as a pianist, playing with his father. The program listed his name as "Gustav," which he had been called since he was young.

Studying at the Royal College of Music

In 1892, Holst wrote an operetta called Lansdown Castle, or The Sorcerer of Tewkesbury, similar to the style of Gilbert and Sullivan. It was performed in February 1893 and was well-received, encouraging him to keep composing. He applied for a scholarship at the Royal College of Music (RCM) in London. He didn't get the composition scholarship that year, but he was accepted as a student. His father borrowed money to cover the first year's costs. Holst moved to London in May 1893. Money was tight, so he became a vegetarian. Two years later, he finally received a scholarship, which helped financially, but he kept his simple lifestyle.

At the RCM, Holst studied piano, organ, trombone, and instrumentation. He also studied composition with Charles Villiers Stanford.

To support himself, Holst played the trombone professionally. He played at seaside resorts in the summer and in London theaters in the winter. His daughter, Imogen Holst, who wrote his biography, said that his earnings allowed him to buy necessities like food, lodging, music paper, and tickets to hear operas at Covent Garden. He sometimes played in symphony concerts, even under the famous conductor Richard Strauss in 1897.

Like many musicians of his time, Holst was fascinated by Wagner's music. At first, he didn't like Wagner's Götterdämmerung when he heard it in 1892. But his friend Fritz Hart encouraged him, and Holst quickly became a huge fan. Wagner's music replaced Sullivan's as the main influence on Holst's own compositions. For a while, as Imogen said, "bits of Tristan appeared on nearly every page of his own songs." Stanford admired some of Wagner's works, but he didn't like Holst's Wagner-inspired pieces, telling him, "It won't do, me boy; it won't do." Holst respected Stanford, calling him "the one man who could get any one of us out of a technical mess." However, he felt that his fellow students influenced his development more than his teachers.

In 1895, around his twenty-first birthday, Holst met Ralph Vaughan Williams. They became lifelong friends and Vaughan Williams had the biggest influence on Holst's music. Stanford taught his students to be critical of their own work, but Holst and Vaughan Williams became each other's main critics. They would play their newest compositions for each other while still working on them. Vaughan Williams later said that students learn more from their friends than from their teachers. In 1949, he wrote that Holst believed his music was influenced by his friend, and the same was certainly true for Vaughan Williams.

Also in 1895, the 200th anniversary of Henry Purcell was celebrated. Performances included Stanford conducting Dido and Aeneas. This work deeply impressed Holst. Years later, he admitted that his search for "the musical idiom of the English language" was "unconsciously" inspired by hearing the singing style in Purcell's Dido.

Another early influence was William Morris, a famous artist and writer. Vaughan Williams said that Holst "discovered a feeling of unity with his fellow men" which made him a great teacher. This feeling, rather than strong political beliefs, led him to join the Socialist League while still a student. They met at Morris's home, Kelmscott House. There, Holst attended talks by Morris and Bernard Shaw. Holst's own socialist views were moderate, but he enjoyed the club for the good company and his admiration for Morris. His ideas were influenced by Morris's, but with a different focus. Morris wanted art, education, and freedom for everyone, not just a few. Holst said that art is not for everyone, but only for a chosen few. However, he believed the only way to find those few was to bring art to everyone. He was invited to conduct the Hammersmith Socialist Choir, teaching them old songs called madrigals, choruses by Purcell, and works by Mozart, Wagner, and himself. One of his singers was Emily Isobel Harrison, a beautiful soprano two years younger than him. He fell in love with her, and they got engaged, though they couldn't marry right away because Holst earned so little money.

Becoming a Professional Musician

In 1898, the RCM offered Holst another year's scholarship, but he felt he had learned enough and needed to "learn by doing." Some of his compositions were published and performed. The year before, The Times newspaper praised his song "Light Leaves Whisper."

Even with some successes, Holst found that "man cannot live by composition alone." He took jobs as an organist at various London churches and continued playing the trombone in theater orchestras. In 1898, he became the main trombonist for the Carl Rosa Opera Company and toured with the Scottish Orchestra. He was a skilled player, even though not a superstar, and was praised by the famous conductor Hans Richter. His salary was barely enough to live on, so he also played in a popular orchestra called the "White Viennese Band."

Holst enjoyed playing for this band and learned a lot about musical expression from its conductor. However, he longed to spend all his time composing and found playing for light orchestras "a wicked and loathsome waste of time." Vaughan Williams didn't fully agree. He admitted some of the music was "trashy" but thought it helped Holst. He believed Holst's experience as an orchestral player gave him a "sure touch" in his orchestral writing.

With a steady, though small, income, Holst was able to marry Isobel on June 22, 1901. Their marriage lasted until his death. They had one child, Imogen, born in 1907. On April 24, 1902, Holst's symphony The Cotswolds was performed for the first time. Its slow movement was a tribute to William Morris, who had died in 1896. In 1903, Adolph von Holst died, leaving a small inheritance. Holst and his wife decided to spend it all on a holiday in Germany, as they were always short on money.

Composer and Teacher

While in Germany, Holst thought about his career. In 1903, he decided to stop playing in orchestras and focus on composing. But his earnings as a composer were too low to live on. So, two years later, he accepted a teaching job at James Allen's Girls' School in Dulwich, where he worked until 1921. He also taught at the Passmore Edwards Settlement, where he introduced two Bach pieces to British audiences for the first time. The two teaching jobs he is most famous for were as music director at St Paul's Girls' School in Hammersmith (from 1905 until his death) and as music director at Morley College (from 1907 to 1924).

Vaughan Williams wrote that at St Paul's Girls' School, Holst replaced the "childish sentimentality" often given to schoolgirls with serious music by Bach. Many of Holst's students at St Paul's went on to have successful music careers.

About Holst's impact at Morley College, Vaughan Williams said that Holst had to break down "a bad tradition." At first, his high demands made many students leave. But he kept going, and slowly built up a group of dedicated music lovers.

According to composer Edmund Rubbra, who studied with Holst in the early 1920s, Holst was a teacher who brought in modern scores like Petrushka instead of old textbooks. He never forced his own ideas on his students. Rubbra remembered that Holst would understand a student's difficulties and gently guide them to find their own solutions. He would suggest changes, but only if the student agreed. Holst often removed unnecessary parts from music because he disliked anything extra.

As a composer, Holst was often inspired by literature. He set poems by Thomas Hardy and Robert Bridges to music. A special influence was Walt Whitman, whose words he used in "Dirge for Two Veterans" and The Mystic Trumpeter (1904). He also wrote an orchestral piece called Walt Whitman Overture in 1899. While touring with the Carl Rosa company, Holst read books by Max Müller, which sparked his interest in Sanskrit texts, especially the Rig Veda hymns. He found the existing English translations not very good, so he decided to make his own, even though he wasn't a skilled linguist. In 1909, he enrolled at University College London to study the language.

Imogen Holst commented on his translations: "He was not a poet, and sometimes his verses seem simple. But they are never unclear or messy, because he aimed for words that would be 'clear and dignified' and would 'lead the listener into another world'." His music based on Sanskrit texts included Sita (1899–1906), a three-act opera. He also wrote Savitri (1908), a short opera for a small group of musicians, based on a story from the Mahabharata. Other works included four groups of Hymns from the Rig Veda (1908–14) and two pieces based on texts by Kālidāsa: Two Eastern Pictures (1909–10) and The Cloud Messenger (1913).

Around the late 1800s, British musicians became very interested in national folk music. Some composers, like Sullivan, didn't care much, but others, like Parry and Stanford, helped start the Folk-Song Society. Parry believed that by rediscovering English folk songs, English composers could find a true national voice. Vaughan Williams was an early and eager supporter, traveling the English countryside to collect folk songs. These songs influenced Holst. Although not as passionate as his friend, Holst used many folk melodies in his own music and arranged folk songs collected by others. The Somerset Rhapsody (1906–07) was written at the suggestion of folk-song collector Cecil Sharp and used tunes Sharp had written down. Holst called its performance in 1910 "my first real success." A few years later, Holst became excited by another musical discovery: the rediscovery of English madrigal composers. Weelkes was his favorite Tudor composer, but Byrd also meant a lot to him.

Holst loved rambling (long walks). He walked a lot in England, Italy, France, and Algeria. In 1908, he traveled to Algeria for his asthma and depression, which he suffered from after his opera Sita didn't win a prize. This trip inspired his suite Beni Mora, which included music he heard in the Algerian streets. Vaughan Williams said that if this unique work had been played in Paris instead of London, it would have made Holst famous across Europe.

The 1910s

In June 1911, Holst and his Morley College students performed Purcell's The Fairy-Queen for the first time since the 1600s. The original music had been lost and was only recently found. Twenty-eight Morley students copied all the vocal and orchestral parts, which was 1,500 pages of music! It took them almost 18 months to copy it in their free time. A concert performance was given, and The Times newspaper praised Holst for a "most interesting and artistic performance."

After this success, Holst was disappointed the next year by the cool reception of his choral work The Cloud Messenger. He traveled again, joining friends in Spain. During this holiday, one of his friends introduced Holst to astrology, which later inspired his famous suite The Planets. Holst continued to create horoscopes for his friends for the rest of his life and called astrology his "pet vice."

In 1913, St Paul's Girls' School opened a new music building. Holst composed St Paul's Suite for the occasion. The new building had a sound-proof room where he could work without being disturbed. Holst and his family moved to a house near the school. For six years, they had lived in a house overlooking the Thames, but the foggy river air affected his breathing. For weekends and holidays, Holst and his wife bought a cottage in Thaxted, Essex, a village with old buildings and many walking paths. In 1917, they moved to a house in the center of Thaxted, where they stayed until 1925.

In Thaxted, Holst became friends with the Rev Conrad Noel, known as the "Red Vicar." Noel supported the Independent Labour Party and many ideas that were unpopular with traditional people. Noel also encouraged old folk dances and processions as part of church ceremonies, which caused arguments among some churchgoers. Holst sometimes played the organ and led the choir at Thaxted Parish Church. He also became interested in bell-ringing. He started an annual music festival at Whitsuntide in 1916. Students from Morley College and St Paul's Girls' School performed with local people.

Holst's carol, "This Have I Done for My True Love", was dedicated to Noel. It was first performed at the Third Whitsun Festival in Thaxted in May 1918. During that festival, Noel, who supported Russia's October Revolution, asked for more political involvement from those in the church. He said some of Holst's students were just "camp followers," which offended them. Holst, wanting to protect his students from church conflicts, moved the Whitsun Festival to Dulwich. However, he continued to help with the Thaxted choir and play the church organ sometimes.

First World War

When World War I started, Holst tried to join the army but was rejected because he was not fit for military service. He felt frustrated that he couldn't help with the war effort. His wife became an ambulance driver. Vaughan Williams and Holst's brother Emil went to fight in France. Holst's friends, the composers George Butterworth and Cecil Coles, were killed in battle. Holst continued to teach and compose. He worked on The Planets and prepared his short opera Savitri for performance. It was first performed in December 1916 by students. It didn't get much attention then, but when it was professionally staged five years later, it was called "a perfect little masterpiece." In 1917, he wrote The Hymn of Jesus for choir and orchestra, which was not performed until after the war.

In 1918, as the war was ending, Holst finally had a chance to serve. The music section of the YMCA (a charity) needed volunteers to work with British troops in Europe who were waiting to go home. Morley College and St Paul's Girls' School gave him a year off. But there was one problem: the YMCA thought his last name, "von Holst," sounded too German. So, in September 1918, he officially changed his name to "Holst." He was appointed the YMCA's music organizer for the Near East, based in Salonica, Greece.

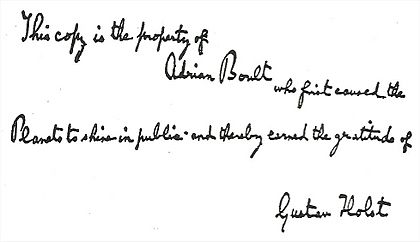

Holst had a spectacular send-off. The conductor Adrian Boult remembered that Holst came to his office and said, "Adrian, the YMCA is sending me to Salonica soon. And Balfour Gardiner, bless his heart, has given me a parting gift: the Queen's Hall, full of the Queen's Hall Orchestra for a whole Sunday morning. So we're going to do The Planets, and you've got to conduct!" Everyone rushed to get things ready. The girls at St Paul's helped copy the orchestral parts, and the women of Morley and St Paul's girls learned the choir part for the last movement.

The performance was on September 29 for a special audience, including Sir Henry Wood and most of London's professional musicians. Five months later, while Holst was in Greece, Boult introduced The Planets to the public in February 1919. Holst sent him a long letter with suggestions, but couldn't convince him to play the whole suite. Boult believed that about half an hour of such new music was all the public could handle at first, so he only played five of the seven movements that time.

Holst enjoyed his time in Salonica. He visited Athens, which greatly impressed him. His musical duties were varied, and he even had to play the violin in the local orchestra sometimes, though he said he wasn't much help. He returned to England in June 1919.

After the War

When he returned from Greece, Holst went back to teaching and composing. Besides his existing work, he accepted a teaching position in composition at the University of Reading. He also joined Vaughan Williams in teaching composition at their old school, the RCM. Inspired by Adrian Boult's conducting classes, Holst tried to further music education for women. He suggested to the headmistress of St Paul's Girls' School that Boult should give classes there, saying, "It would be glorious if the SPGS turned out the only women conductors in the world!" In his soundproof room at the school, he composed the Ode to Death, a setting of a poem by Whitman. Vaughan Williams considered it one of Holst's most beautiful choral works.

In his forties, Holst suddenly became very popular. The New York Philharmonic and Chicago Symphony Orchestra competed to be the first to play The Planets in the US. The success of The Planets was followed in 1920 by an enthusiastic reception for The Hymn of Jesus. The Observer called it "one of the most brilliant and one of the most sincere pieces of choral and orchestral expression heard for some years." The Times called it "undoubtedly the most strikingly original choral work which has been produced in this country for many years."

To his surprise and dislike, Holst was becoming famous. He was a shy person and fame was completely against his nature. As music expert Byron Adams says, "he struggled for the rest of his life to escape the web of flashy publicity, public misunderstanding, and professional jealousy caused by this unwanted success." He turned down honors and awards and refused to give interviews or sign autographs.

Holst's comic opera The Perfect Fool (1923) was often seen as a parody of Wagner's Parsifal, though Holst strongly denied it. The opera, with famous singer Maggie Teyte and conductor Eugene Goossens, was very well received at its first performance. In 1923, at a concert, Holst slipped and fell, getting a concussion. He seemed to recover well and accepted an invitation to the US, where he lectured and conducted at the University of Michigan. After he returned, he found himself in even more demand to conduct, prepare his older works for publication, and teach. The stress was too much. On doctor's orders, he canceled all professional engagements in 1924 and went back to Thaxted. In 1925, he resumed his work at St Paul's Girls' School, but did not return to his other jobs.

Later Years

Holst's ability to compose improved almost immediately after he stopped his other work. His pieces from this time include the Choral Symphony using words by Keats. A short Shakespearean opera, At the Boar's Head, followed. Neither of these had the immediate popularity of A Moorside Suite for brass band, written in 1928.

In 1927, the New York Symphony Orchestra asked Holst to write a symphony. Instead, he wrote an orchestral piece called Egdon Heath, inspired by Thomas Hardy's Wessex, a fictional region in his novels. It was first performed in February 1928, a month after Hardy's death, at a memorial concert. By this time, the public's brief excitement for all things Holstian was fading. The piece was not well received in New York. Olin Downes in The New York Times said that "the new score seemed long and undistinguished." The day after the American performance, Holst conducted the City of Birmingham Orchestra in the British premiere. The Times acknowledged the bleakness of the work but said it matched Hardy's serious view of the world. Holst had been upset by bad reviews of some of his earlier works, but he didn't care about the critics' opinions of Egdon Heath, which he considered his "most perfectly realized composition."

Towards the end of his life, Holst wrote the Choral Fantasia (1930). He was also asked by the BBC to write a piece for military band. The resulting prelude and scherzo Hammersmith was a tribute to the place where he had lived most of his life. The composer and critic Colin Matthews believes the work is "as serious in its way as Egdon Heath." It was unlucky to be premiered at a concert that also featured the London premiere of Walton's Belshazzar's Feast, which somewhat overshadowed it.

Holst wrote music for a British film, The Bells (1931), and found it amusing to be an extra in a crowd scene. Both the film and its music are now lost. He wrote a "jazz band piece" that his daughter Imogen later arranged for orchestra as Capriccio. Having composed operas throughout his life with varying success, Holst found the right style for his last opera, The Wandering Scholar, which Matthews calls "economical and direct."

Harvard University offered Holst a teaching position for the first six months of 1932. He arrived via New York and was happy to see his brother, Emil, whose acting career had taken him to Broadway. But Holst was bothered by the constant attention from reporters and photographers. He enjoyed his time at Harvard, but became ill there with a duodenal ulcer that kept him unwell for several weeks. He returned to England, joined briefly by his brother for a holiday in the Cotswolds. His health declined, and he withdrew further from musical activities. One of his last efforts was guiding the young players of the St Paul's Girls' School orchestra through one of his final compositions, the Brook Green Suite, in March 1934.

Holst died in London on May 25, 1934, at age 59. He passed away from heart failure after an operation on his ulcer. His ashes were buried at Chichester Cathedral in Sussex, near the memorial to Thomas Weelkes, his favorite Tudor composer. Bishop George Bell gave the memorial speech at the funeral, and Vaughan Williams conducted music by Holst and himself.

Holst's Musical Style

How Holst Composed

Holst's use of folk music, not just for melodies but for its simple and direct expression, helped him create a style that many people, even his fans, found serious and intellectual. This is different from how most people know Holst through The Planets, which some believe hides his true originality as a composer. Against claims that his music was cold, his daughter Imogen pointed to Holst's "sweeping modal tunes moving reassuringly above the steps of a descending bass." Music critic Michael Kennedy also noted the warmth in some of his later songs.

Many of Holst's musical traits—like unusual time signatures, rising and falling scales, repeated musical patterns (called ostinato), and using two or more keys at once (called bitonality or polytonality)—made him stand out from other English composers. Vaughan Williams said that Holst always expressed what he wanted to say in his music, directly and clearly. He wasn't afraid to be obvious when needed, nor did he hesitate to be mysterious when that suited his purpose. Kennedy thought that Holst's simple style was partly because of his poor health. However, as an experienced musician and orchestra member, Holst understood music from the players' point of view. He made sure that, no matter how challenging, their parts were always playable.

Early Music Works

Even though Holst wrote many pieces, especially songs, during his student days and early adulthood, he later called almost everything he wrote before 1904 "early horrors." However, composer and critic Colin Matthews still sees an "instinctive orchestral flair" even in these early works. Of the few pieces from this time that show some originality, Matthews points to the G minor String Trio of 1894 as Holst's first truly original work. Matthews and Imogen Holst both highlight the "Elegy" movement in The Cotswold Symphony (1899–1900) as one of the more skilled early works. Imogen also sees glimpses of her father's true self in the 1899 Suite de ballet and the Ave Maria of 1900. They both believe Holst found his real voice in his setting of Whitman's poem, The Mystic Trumpeter (1904). In this piece, the trumpet calls that are a key part of "Mars" in The Planets are briefly heard. In this work, Holst first used the technique of bitonality.

Experimental Years

At the start of the 20th century, it seemed Holst might follow composers like Schoenberg into a late Romantic style. Instead, Holst later realized that hearing Purcell's Dido and Aeneas made him search for a "musical idiom of the English language." The folk song revival also encouraged Holst to find inspiration from other sources during the first decade of the new century.

Indian Period

Holst's interest in Indian mythology, shared by many people at the time, first appeared in his opera Sita (1901–06). While working on Sita, Holst also created other Indian-themed pieces. Then, through Vaughan Williams, Holst discovered and admired the music of Ravel, whom he considered a "model of purity."

The combined influences of Ravel, Hindu spirituality, and English folk tunes helped Holst move beyond the strong influences of Wagner and Richard Strauss and create his own style. Imogen Holst noted that her father suggested that one should follow Wagner until he leads you to new things. She observed that while much of his opera Sita is "good old Wagnerian bawling," towards the end, the music changes, and the calm phrases of the hidden chorus are in Holst's own unique style.

According to Rubbra, the publication of Holst's Rig Veda Hymns in 1911 was a major step in the composer's development. Before this, Holst's music was clear, but harmonically, there was little to make him stand out in modern music. Music expert Dickinson describes these Vedic settings as more pictorial than religious. While the quality varies, the sacred texts clearly "touched vital springs in the composer's imagination." Although the music of Holst's Indian verse settings generally remained Western in style, in some of the Vedic settings, he experimented with Indian raga (scales).

The short opera Savitri (1908) is written for three solo singers, a small hidden female choir, and a small group of instruments. Music critic John Warrack comments on the "extraordinary expressive subtlety" with which Holst uses these few forces. He describes the work as unique for its time due to its compact intimacy. Dickinson considers it a significant step for Holst's musical vision. Of the Kālidāsa texts, Dickinson finds The Cloud Messenger (1910–12) to be a confusing mix of events. However, the Two Eastern Pictures (1911) leave a "more memorable final impression."

Folk Songs and Other Influences

Holst's Indian-themed works were only part of his compositions from 1900 to 1914. A very important factor in his musical growth was the English folk song revival. This is clear in the orchestral suite A Somerset Rhapsody (1906–07). This piece was originally meant to use eleven folk song themes, but this was later reduced to four. Dickinson notes that with its strong overall structure, Holst's composition "rises beyond the level of a song-selection." Imogen Holst acknowledged that Holst's discovery of English folk songs "transformed his orchestral writing." She added that composing A Somerset Rhapsody helped him get rid of the complex harmonies that had been common in his early works. In the Two Songs without Words of 1906, Holst showed he could create his own original music using the folk style.

In the years before World War I, Holst composed in many different styles. Matthews considers the depiction of a North African town in the Beni Mora suite of 1908 to be Holst's most unique work up to that point. The third movement even gives a hint of minimalism with its constant repetition of a four-bar tune. Holst wrote two suites for military band, in E flat (1909) and F major (1911). The first of these became and remains a very popular piece for brass bands. This highly original work was a big change from the usual transcriptions and opera selections that filled band music. Also in 1911, he wrote Hecuba's Lament, based on a Greek play. In 1912, Holst composed two psalm settings, where he experimented with plainsong (simple, ancient church music). The same year saw the popular St Paul's Suite and the failure of his large orchestral work Phantastes.

Holst's Best-Known Works

The Planets

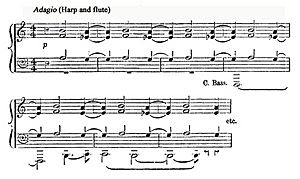

Holst got the idea for The Planets in 1913. This was partly because of his interest in astrology and his desire to create a large orchestral work after Phantastes failed. Holst began composing The Planets in 1914. The movements were not written in their final order. "Mars" was first, then "Venus" and "Jupiter." "Saturn," "Uranus," and "Neptune" were all composed in 1915, and "Mercury" was finished in 1916.

Each planet has its own distinct character. Dickinson notes that "no planet borrows color from another." In "Mars," a strong, uneven rhythm of five beats, combined with trumpet calls and harsh harmonies, creates battle music. Short says this music is unique in showing violence and terror, as Holst wanted to show the reality of war, not glorify heroism. In "Venus," Holst used music from an unfinished vocal work to create the opening. The main feeling in this movement is peacefulness and longing. "Mercury" is full of uneven rhythms and quick changes of tune, showing the speedy flight of the winged messenger. "Jupiter" is famous for its central melody, "Thaxted", which Dickinson calls "a fantastic relaxation." Dickinson and other critics have criticized the later use of this tune in the patriotic hymn "I Vow to Thee, My Country"—even though Holst fully agreed to it.

For "Saturn," Holst again used an earlier vocal piece as the basis. Here, repeated chords represent the unstoppable approach of old age. "Uranus," which follows, has elements of Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique and Dukas's The Sorcerer's Apprentice. It depicts a magician who "disappears in a puff of smoke as the sound of the movement fades." "Neptune," the final movement, ends with a wordless female choir slowly fading away. Warrack compares this effect to "unresolved timelessness... never ending, since space does not end, but drifting away into eternal silence." Besides his agreement for "I Vow to Thee...", Holst insisted that the whole work should be played together and opposed performing individual movements. However, Imogen wrote that the piece "suffered from being quoted in snippets as background music."

Later Compositions

During and after composing The Planets, Holst wrote or arranged many vocal and choral works. Many of these were for the wartime Thaxted Whitsun Festivals from 1916–18. They include the Six Choral Folksongs of 1916, based on West Country tunes. Holst downplayed such music as "a limited form of art." However, composer Alan Gibbs believes Holst's set is as good as Vaughan Williams's Five English Folk Songs of 1913.

Holst's first major work after The Planets was The Hymn of Jesus, finished in 1917. The words come from an ancient text, the apocryphal Acts of John. Holst prepared the translation from Greek with help from Clifford Bax and Jane Joseph. Head comments on the Hymns new style: "Holst had instantly moved away from the old-fashioned sentimental oratorio and created a work that was a forerunner of pieces like those John Tavener would write in the 1970s." Matthews wrote that the Hymns "ecstatic" quality is matched in English music "perhaps only by Tippett's The Vision of Saint Augustine." The music includes ancient church chants, two choirs placed apart to create dialogue, dance sections, and "explosive chord changes."

In the Ode to Death (1918–19), the quiet, calm mood is seen by Matthews as a sudden change after the spiritual energy of the Hymn. Warrack refers to its distant tranquility. Imogen Holst believed the Ode showed Holst's private feelings about death. The piece has rarely been performed since its first showing in 1922.

The influential critic Ernest Newman considered The Perfect Fool "the best of modern British operas." However, its unusual short length (about an hour) and its funny, whimsical nature made it different from typical operas. Only the ballet music from the opera, which The Times called "the most brilliant thing," has been regularly performed since 1923. Holst's story for the opera received much criticism.

Later Works

Before his forced rest in 1924, Holst showed a new interest in counterpoint (combining different melodies). This was seen in his Fugal Overture of 1922 for orchestra and the Fugal Concerto of 1923 for flute, oboe, and strings. In his last ten years, he wrote songs and smaller pieces mixed with major works and new styles. The 1925 Terzetto for flute, violin, and oboe, where each instrument plays in a different key, is cited by Imogen as Holst's only successful chamber music piece. Of the Choral Symphony finished in 1924, Matthews writes that after several good movements, the ending is disappointing. Holst's second-to-last opera, At the Boar's Head (1924), is based on tavern scenes from Shakespeare's Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2. The music, which uses old English melodies, is lively and energetic.

Egdon Heath (1927) was Holst's first major orchestral work after The Planets. Matthews describes the music as "elusive and unpredictable" with three main parts: a slow, wandering melody for strings, a sad brass procession, and restless music for strings and oboe. The mysterious dance near the end is "the strangest moment in a strange work." Richard Greene describes the piece as a slow dance with a simple, rocking melody, but lacking the power of The Planets and sometimes boring. A more popular success was A Moorside Suite for brass band, written as a test piece for a competition in 1928. While it follows brass-band traditions, the suite has Holst's clear style.

After this, Holst tried opera again in a cheerful way with The Wandering Scholar (1929–30). Imogen calls the music "Holst at his best in a playful mood." Vaughan Williams commented on the lively, folk-like rhythms.

Holst composed few large works in his final years. A Choral Fantasia of 1930 was written for a festival. It begins and ends with a soprano soloist and includes a significant organ solo. Besides his unfinished final symphony, Holst's remaining works were for small groups. The eight Canons of 1932 were dedicated to his students. The Brook Green Suite (1932), written for the St Paul's School orchestra, was a later companion piece to the St Paul's Suite. The Lyric Movement for viola and small orchestra (1933) was written for Lionel Tertis. This quiet and thoughtful piece was slow to become popular among viola players. Robin Hull praised its "clear beauty." Holst's final composition, the orchestral scherzo movement of a planned symphony, contains features typical of much of Holst's earlier music.

Recordings of Holst's Music

Holst made some recordings, conducting his own music. For the Columbia company, he recorded Beni Mora, the Marching Song, and the complete Planets with the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) in 1922. Early recording technology had limitations. For example, the gradual fade-out of women's voices at the end of "Neptune" couldn't be fully captured, and lower strings had to be replaced by a tuba for a better bass sound. With an unnamed string orchestra, Holst recorded the St Paul's Suite and Country Song in 1925. Columbia's main competitor, HMV, also released recordings of some of the same music. When electrical recording improved sound quality dramatically, Holst and the LSO re-recorded The Planets for Columbia in 1926.

In the early days of LP records, not much of Holst's music was available. By the early 2000s, most of his major and many of his smaller orchestral and choral works had been released on CD. Of his operas, Savitri, The Wandering Scholar, and At the Boar's Head have been recorded.

Holst's Legacy

Warrack emphasizes that Holst gained a deep understanding of the importance of folk song. In it, he found "a new idea not only of how melody might be organized, but of what it meant for developing a mature artistic language." Holst did not start or lead a specific style of composition. However, he influenced both his friends and later composers. According to Short, Vaughan Williams called Holst "the greatest influence on my music," although Matthews believes they influenced each other equally. Among later composers, Michael Tippett is recognized by Short as Holst's "most significant artistic successor." Tippett, who took over from Holst as music director at Morley College, kept Holst's musical spirit alive there. Tippett later wrote that Holst "seemed to look right inside me, with an acute spiritual vision." Kennedy observes that "a new generation of listeners... recognized in Holst the source of much that they admired in the music of Britten and Tippett." Holst's student Edmund Rubbra acknowledged how he and other younger English composers adopted Holst's simple style.

Short mentions other English composers who owe something to Holst, especially William Walton and Benjamin Britten. He also suggests that Holst's influence might have spread further. Most importantly, Short sees Holst as a composer for everyone. Holst believed it was a composer's job to create music for practical uses—festivals, celebrations, ceremonies, Christmas carols, or simple hymn tunes. So, Short says, "many people who may never have heard any of [Holst's] major works... have nevertheless derived great pleasure from hearing or singing such small masterpieces as the carol 'In the Bleak Midwinter'."

On September 27, 2009, after a weekend of concerts at Chichester Cathedral in memory of Holst, a new memorial was unveiled. This marked the 75th anniversary of the composer's death. It is inscribed with words from The Hymn of Jesus: "The heavenly spheres make music for us." In April 2011, a BBC television documentary, Holst: In the Bleak Midwinter, explored Holst's life, especially his support for socialism and working people. Holst's birthplace, 4 Pittville Terrace (now 4 Clarence Road) in Pittville, Cheltenham, is now a Holst museum and is open to visitors.

See also

In Spanish: Gustav Holst para niños

In Spanish: Gustav Holst para niños