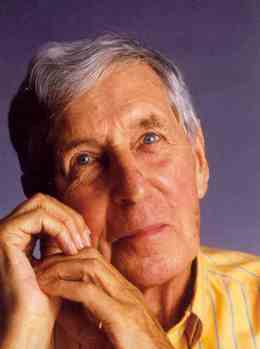

Michael Tippett facts for kids

Sir Michael Kemp Tippett (born January 2, 1905 – died January 8, 1998) was an English composer. He became well-known during and after the Second World War. Many people thought he was one of the most important British composers of the 20th century, alongside Benjamin Britten. Some of his most famous works include the oratorio A Child of Our Time, the orchestral piece Fantasia Concertante on a Theme of Corelli, and the opera The Midsummer Marriage.

Tippett's musical talent grew slowly. He didn't publish any of his works until he was 30 years old, and he even destroyed some of his early pieces. In his younger years, his music was often gentle and flowing. Later, in the 1950s, his style became more experimental. He started to include new sounds, like jazz and blues, especially after visiting America in 1965. While more people started to appreciate his music, some critics didn't like these changes. From about 1976, his later works began to sound more like his earlier, lyrical music. Tippett received many awards during his life, but opinions on his music have varied, with his earlier works often receiving the most praise.

Tippett was a pacifist (someone who believes war is wrong) after 1940. He was even sent to prison in 1943 for refusing to do war-related duties. He was a strong supporter of music education and often shared his ideas about music on the radio and in his writings.

Life of Michael Tippett

Family Background

The Tippett family came from Cornwall, a county in England. Michael Tippett's grandfather, George Tippett, moved to London in 1854 to make money in business. He was a lively person with a strong singing voice. Michael's father, Henry, born in 1858, became a successful lawyer and was quite wealthy when he married in 1903. Henry Tippett was a very open-minded person for his time.

Henry Tippett married Isabel Kemp, who came from a large, well-off family. Isabel's cousin was Charlotte Despard, a famous activist who fought for women's rights and other causes. Isabel was influenced by Charlotte and had an artistic talent, like her mother. Michael was born on January 2, 1905, in Eastcote, near London, the second son of Henry and Isabel.

Childhood and Schooling

Soon after Michael was born, his family moved to Wetherden in Suffolk. Michael started his education in 1909 with a governess and tutors. This is when he first learned to play the piano. He loved to improvise on the piano, calling it "composing," even though he didn't fully understand what that meant. In 1914, he became a boarder at Brookfield Preparatory School in Dorset. Later, in 1918, he won a scholarship to Fettes College in Edinburgh, where he continued piano lessons, sang in the choir, and started learning the pipe organ. He found this school difficult. In 1920, he moved to Stamford School in Lincolnshire.

Around this time, Michael's parents moved to France, but Michael and his brother stayed in England for school, visiting France for holidays. Michael enjoyed Stamford School much more than Fettes. He improved a lot in his studies and music. His piano teacher, Frances Tinkler, introduced him to the music of famous composers like Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, and Chopin. Even though his parents wanted him to go to Cambridge University, Michael was determined to become a composer.

By 1922, Tippett had become quite independent. He left Stamford School but continued his music lessons. He also started studying a book called Musical Composition by Charles Villiers Stanford, which became very important for his own composing. In 1923, his father agreed to support him in studying at the Royal College of Music (RCM) in London. He was accepted even without all the usual entry qualifications.

Royal College of Music

Tippett started at the RCM in 1923, when he was 18. He was very ambitious, but his musical knowledge was still basic. Living in London opened up a new world of music for him. He went to many concerts, operas, and ballets. He heard famous singers and saw concerts conducted by composers like Stravinsky and Ravel. He also learned about older music by attending masses at Westminster Cathedral.

At the RCM, Tippett's first composition teacher was Charles Wood, who taught him about musical forms using the works of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven. After Wood died, Tippett studied with C.H. Kitson, but they didn't get along well. Tippett also studied conducting and learned a lot about orchestral instruments and the music of composers like Delius and Debussy.

In 1924, Tippett became the conductor of an amateur choir in Oxted, Surrey. He worked with this choir for many years, even combining it with a local theater group to put on performances. He passed his Bachelor of Music (BMus) exams in 1928. Instead of continuing his studies, Tippett decided to leave the academic world and focus on his music.

Early Career

Early Compositions

After leaving the RCM, Tippett settled in Oxted to continue working with his choir and theater group and to compose. He also taught French at a school to support himself. In 1930, he put on a concert entirely of his own works. However, he was not happy with these pieces and decided he needed more training. In September 1930, he went back to the RCM to study counterpoint and orchestration. This period was very important for him to find his own unique musical style.

In 1931, Tippett conducted his Oxted choir in a performance of Handel's Messiah. He tried to use the same number of singers and musicians that Handel would have used, which was unusual at the time and attracted a lot of attention.

New Ideas and Music

In 1932, Tippett moved to a cottage in Limpsfield, given to him by friends so he could focus on composing. He met important writers like W. H. Auden and T. S. Eliot, who he considered his "spiritual father." Tippett became more interested in political ideas. He stopped teaching and became the conductor of the South London Orchestra, which was made up of unemployed musicians.

In the summers of 1932 and 1934, Tippett led musical activities at work camps for unemployed miners in northern England. He helped stage a shorter version of The Beggar's Opera and wrote music for a new folk opera called Robin Hood. These shows were very popular. Some of the music from Robin Hood was later used in his Birthday Suite for Prince Charles in 1948.

Tippett briefly joined the British Communist Party in 1935 but left after a few months because of different political views. He realized that too much political activity would take him away from his main goal: becoming a recognized composer. A big step in his career came in December 1935, when his String Quartet No. 1 was performed in London. This piece is considered the first important work in his collection.

Towards Maturity

Personal Growth

Before the Second World War began in September 1939, Tippett released two more works: the Piano Sonata No. 1 (1938) and the Concerto for Double String Orchestra (1940). As the world became more tense, Tippett went through a difficult emotional time. He sought help from a psychotherapist, John Layard, who helped him understand his feelings and dreams.

A Child of Our Time

While working on his personal growth, Tippett looked for a theme for a major musical work, like an opera or an oratorio. He wanted it to reflect both the world's problems and his own experiences. He decided to base his work on the murder of a German diplomat by a young Jewish refugee, Herschel Grynszpan, in Paris. This event led to Kristallnacht (Crystal Night), a terrible attack on Jewish people and their property in Nazi Germany in November 1938.

Tippett hoped the poet T. S. Eliot would write the words for his oratorio, but Eliot advised him to write his own text. Tippett called his oratorio A Child of Our Time. He used a three-part structure, similar to Handel's Messiah. A unique part of his oratorio was using North American spirituals (songs with religious themes, often from African-American traditions) instead of traditional church songs. These spirituals helped to shape the music and the story. Tippett began composing the oratorio in September 1939, right after the war started.

Morley College, War, and Imprisonment

Because of the war, the South London Orchestra was temporarily closed. Tippett returned to teaching. In October 1940, he became the Director of Music at Morley College, even though its buildings had been badly damaged by a bomb. Tippett worked to rebuild the college's music program, using temporary spaces and whatever resources he could find. He brought back the Morley College Choir and orchestra and created interesting concert programs that mixed old music with new works by composers like Stravinsky.

He continued the college's focus on the music of Purcell. A performance of Purcell's Ode to St Cecilia in 1941, with new arrangements, attracted a lot of attention. The music staff at Morley College grew with the addition of musicians who had come to England as refugees from Europe.

A Child of Our Time was finished in 1941, but there were no immediate plans to perform it. Tippett's Fantasia on a Theme of Handel for piano and orchestra was performed in 1942. His String Quartet No. 2 was first played a year later. The first recording of Tippett's music, his Piano Sonata No. 1, was released in 1941 and was well-received. In 1942, Schott Music began publishing Tippett's works, a partnership that lasted throughout his life.

Tippett was a conscientious objector, meaning he refused to participate in war because of his beliefs. In 1940, he officially joined the Peace Pledge Union. In 1942, a tribunal (a special court) assigned him to non-combatant duties, but Tippett refused this work, believing it went against his principles. In June 1943, after several hearings, he was sentenced to three months in HM Prison Wormwood Scrubs. He served two months and was then left alone by the authorities.

International Acclaim

King Priam and Beyond

In 1960, Tippett moved to a house in the village of Corsham, Wiltshire. By then, he had started working on his second major opera, King Priam. He chose the story of Priam, the mythical king of the Trojans from Homer's Iliad, and wrote his own story for the opera. Because he was so focused on the opera, he wrote only a few smaller pieces during these years. King Priam was first performed in Coventry in May 1962 as part of a festival celebrating the new Coventry Cathedral.

The music in King Priam was very different from Tippett's earlier works. Some people wondered about this big change in his style, but the opera was a great success with both critics and the public. This success, along with a popular BBC broadcast of The Midsummer Marriage in 1963, helped Tippett become recognized as a leading British composer.

After King Priam, Tippett's new compositions, like the Piano Sonata No. 2 (1962) and the Concerto for Orchestra (1963), continued to show the musical style of the opera. His main work in the mid-1960s was the cantata The Vision of Saint Augustine, which is considered a high point in his career. His importance as a national figure was growing. He received a knighthood in 1966, becoming "Sir Michael Tippett."

Wider Horizons

In 1965, Tippett made his first trip to the United States. His experiences in America greatly influenced his music in the late 1960s and early 1970s. You can hear elements of jazz and blues in his third opera, The Knot Garden (1966–69), and in his Symphony No. 3 (1970–72). In 1969, Tippett helped save the Bath International Music Festival from financial trouble and became its artistic director for five years. In 1970, he moved to a quiet house in the countryside. During this time, he wrote pieces like In Memoriam Magistri (1971), a tribute to Stravinsky, and the Piano Sonata No. 3 (1973).

In February 1974, Tufts University in Massachusetts held a "Michael Tippett Festival" in his honor. He also attended the first performance of his opera The Knot Garden in the US. Two years later, he was back in America for a lecture tour. Between these trips, Tippett traveled to Lusaka, Zambia, for the first African performance of A Child of Our Time.

In 1976, Tippett received the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society. The next few years included trips to Java and Bali, where he was fascinated by the sounds of gamelan (traditional Indonesian music) ensembles. He also visited Australia, where he conducted a performance of his Fourth Symphony. In 1979, he used money from selling some of his original music papers to start the Michael Tippett Musical Foundation. This foundation helps young musicians and supports music education.

Tippett remained a pacifist and served as president of the Peace Pledge Union from 1959. In 1977, he spoke out against plans to develop a neutron bomb.

Later Life

In his seventies, Tippett continued to compose and travel, even though his health was declining. His eyesight was getting worse, and he relied more on his musical assistant, Michael Tillett, and his close companion, Meirion Bowen. His main works from the late 1970s were a new opera, The Ice Break, his Symphony No. 4, the String Quartet No. 4, and the Triple Concerto for violin, viola, and cello. The Ice Break was inspired by his American experiences, but some critics found its language difficult. The Triple Concerto includes a part inspired by the gamelan music he heard in Java.

In 1979, Tippett was made a Companion of Honour (CH). In the early 1980s, he worked on his oratorio The Mask of Time, which explored big ideas about humanity's relationship with time and the universe. This oratorio was commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and was first performed in America.

In 1983, Tippett became president of the London College of Music and was appointed a Member of the Order of Merit (OM). By his 80th birthday in 1985, his eyesight was very poor, and he composed less. However, in his final active years, he wrote his last opera, New Year. This futuristic story, with flying saucers and urban violence, was first performed in Houston, Texas, in 1989. It was later brought to Britain in 1990.

Despite his health, Tippett toured Australia in 1989–90 and also visited Senegal. His last major works, written between 1988 and 1993, included Byzantium for soprano and orchestra, the String Quartet No. 5, and The Rose Lake. He intended The Rose Lake to be his final piece, but in 1996, he wrote "Caliban's Song" as a contribution to a celebration of Purcell.

Death

In 1997, Tippett moved from Wiltshire to London to be closer to his friends and caregivers. In November of that year, he made his last trip overseas to Stockholm for a festival of his music. He had a stroke and was taken home, where he died on January 8, 1998, six days after his 93rd birthday. He was cremated on January 15.

Tippett's Music and Legacy

Many people considered Tippett and Britten to be the two best British composers of their generation. After Britten died in 1976, Tippett was widely seen as the most important British composer. However, critics had mixed opinions about his later works. Some felt that his creative power declined after the success of King Priam. Others argued that his later music was just harder to understand because it used a more challenging musical language.

After Tippett's death, his more popular early pieces continued to be played, but there wasn't much public interest in his later works. Performances and recordings became less frequent after his 2005 centenary celebrations. Some critics believe his reputation has fallen since his death, while others predict he will eventually be recognized as one of the most original and powerful musical voices of 20th-century Britain.

Many of Tippett's articles and radio talks were published in collections. In 1991, he published his autobiography, Those Twentieth Century Blues, where he openly discussed his life and relationships. Tippett believed that art could help society by showing parts of human experience that science couldn't explain.

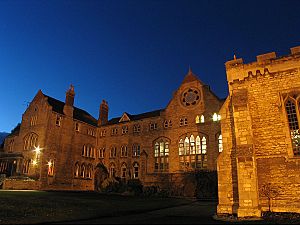

While Tippett didn't create a specific "school" of composition, other composers like David Matthews and William Mathias have said he influenced them. His musical and educational impact continues through the Michael Tippett Foundation. He is also remembered by the Michael Tippett Centre, a concert venue at Bath Spa University. In London, there is also the Heron Academy (formerly The Michael Tippett School), which helps young people with learning disabilities, and it includes the Tippett Music Centre for music education.

Writings by Michael Tippett

Three collections of Tippett's articles and broadcast talks have been published:

- Moving into Aquarius (1959). London, Routledge and Kegan Paul. OCLC 3351563

- Music of the Angels: essays and sketchbooks of Michael Tippett (1980). London, Eulenburg Books. ISBN: 0-903873-60-5

- Tippett on Music (1995). Oxford, Clarendon Press. ISBN: 0-19-816541-2

|

See also

In Spanish: Michael Tippett para niños

In Spanish: Michael Tippett para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |