W. H. Auden facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

W. H. Auden

|

|

|---|---|

Auden in 1939

|

|

| Born |

Wystan Hugh Auden

21 February 1907 York, England

|

| Died | 29 September 1973 (aged 66) Vienna, Austria

|

| Citizenship | British (birth), American (1946) |

| Education | M.A. English language and literature |

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Spouse(s) | Erika Mann (unconsummated marriage, 1935, to provide her with a British passport) |

| Relatives |

|

Wystan Hugh Auden (born February 21, 1907 – died September 29, 1973) was a famous British-American poet. His poems were known for their amazing style and skill. They often talked about politics, good and bad choices, love, and religion. Auden wrote in many different ways and about many different things.

Some of his most famous poems are about love, like "Funeral Blues". Others are about political and social ideas, such as "September 1, 1939". He also wrote about culture and feelings, like in The Age of Anxiety. Some poems, like "For the Time Being", focused on religious themes.

Auden was born in York, England, and grew up near Birmingham. He went to schools in England and studied English at Christ Church, Oxford. After living in Berlin for a short time, he taught at schools in Britain. He also traveled to Iceland and China, writing books about his trips.

In 1939, Auden moved to the United States. He became an American citizen in 1946 but kept his British citizenship. He taught at American universities and later became a visiting professor. For many years, he spent winters in New York and summers in Europe.

He became well-known at 23 with his first book, Poems, in 1930. His plays, written with Christopher Isherwood, made him famous as a writer who supported left-wing political ideas. Auden moved to the U.S. partly to get away from this image. His work in the 1940s, including long poems like "For the Time Being", focused more on religious topics.

He won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1948 for his poem The Age of Anxiety. The title of this poem became a popular way to describe the modern world. From 1956 to 1961, he was a Professor of Poetry at Oxford University. His lectures were very popular and later became a book called The Dyer's Hand.

Auden wrote many essays and reviews about literature, politics, and religion. He also worked on documentary films and plays. Throughout his life, people had different opinions about his work. Some thought he was not as good as other poets, while others, like Joseph Brodsky, called him "the greatest mind of the twentieth century." After he died, his poems became even more famous through movies and TV.

Contents

Auden's Life Story

Childhood and Early Years

W. H. Auden was born in York, England, on February 21, 1907. His father, George Augustus Auden, was a doctor. His mother, Constance Rosalie Auden, had trained to be a missionary nurse. Wystan was the youngest of three sons. His older brother, George, became a farmer, and John became a geologist.

Auden's family had a long history of church leaders. He grew up in a church-going home that followed a traditional form of Anglicanism. He felt that his love for music and language came from the church services he attended as a child. He also believed he had family roots in Iceland. This led to his lifelong interest in Icelandic legends and old Norse stories, which you can see in his writing.

In 1908, his family moved to Solihull, near Birmingham. His father worked there as a school medical officer. Auden's interest in how the mind works began in his father's library. From age eight, he went to boarding schools, coming home for holidays. He often visited the Pennines, an area with old lead-mining towns. These places appeared in many of his poems. For him, the quiet mining village of Rookhope was a "sacred landscape." Until he was 15, he thought he would become a mining engineer. But his love for words had already started to grow.

School Days and Oxford

Auden went to St Edmund's School, Hindhead, in Surrey. There, he met Christopher Isherwood, who later became a famous novelist. At 13, Auden went to Gresham's School in Norfolk. In 1922, a friend asked him if he wrote poetry. Auden then realized that being a poet was what he truly wanted to do. Soon after, he also realized he had lost his religious faith.

In school plays by William Shakespeare, he acted in The Taming of the Shrew in 1922 and The Tempest in 1925. His first poems were published in the school magazine in 1923.

In 1925, he went to Christ Church, Oxford, on a scholarship for biology. But in his second year, he switched to English. There, he learned about Old English poetry from J. R. R. Tolkien's lectures. At Oxford, he met friends like Cecil Day-Lewis, Louis MacNeice, and Stephen Spender. These four were sometimes called the "Auden Group" because they shared similar left-wing ideas. Auden finished Oxford in 1928.

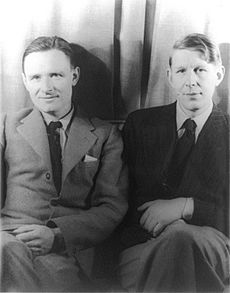

He reconnected with Christopher Isherwood in 1925. For several years, Auden sent his poems to Isherwood for feedback. From 1935 to 1939, they worked together on three plays and a travel book. Friends described Auden as funny, generous, and often lonely. He was very organized with his work but lived in a messy space.

Life in Britain and Europe

In late 1928, Auden left Britain for nine months to go to Berlin. In Berlin, he saw the political and economic problems that later became a big part of his writing. Around this time, Stephen Spender printed a small book of Auden's poems.

When he returned to Britain in 1929, he worked as a tutor. In 1930, his first book, Poems, was published. From 1930, he taught at boys' schools for five years. He was a very popular teacher. In 1933, he had a special experience where he felt a deep love for his fellow teachers. He said this experience later led him to return to the Anglican Church in 1940.

In 1935, Auden married Erika Mann, a novelist, to help her get a British passport. This was a "marriage of convenience" to help her escape the Nazis. They never lived together but remained friends.

From 1935 until 1939, Auden worked as a freelance writer and lecturer. He worked with the GPO Film Unit, making documentary films. Through this, he met and worked with Benjamin Britten, a composer. Auden's plays in the 1930s were performed by the Group Theatre.

His work now showed his belief that a good artist should be like a journalist. In 1936, Auden spent three months in Iceland. He collected material for a travel book, Letters from Iceland (1937), with Louis MacNeice. In 1937, he went to Spain during the Spanish Civil War. He wanted to drive an ambulance but ended up writing propaganda. This visit deeply affected him. He realized that political situations were more complicated than he thought.

He and Isherwood spent six months in China in 1938 during the Second Sino-Japanese War. They wrote a book about it called Journey to a War. On their way back, they stopped in New York and decided to move to the United States.

Many of Auden's poems from the 1930s were inspired by love that was not returned. He was very good at making friends and wanted the stability of marriage. He often did kind acts for others, sometimes in public, like his marriage to Erika Mann. More often, he helped people in private.

Moving to America

Auden and Isherwood sailed to New York City in January 1939. Many people in Britain saw their departure as a betrayal, and Auden's reputation suffered. In April 1939, Isherwood moved to California, and they saw each other less often. Around this time, Auden met the poet Chester Kallman. Auden dedicated his collected poetry books to both Isherwood and Kallman.

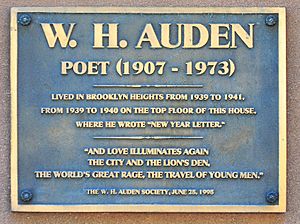

In 1940–41, Auden lived in a house in Brooklyn Heights with other artists, including Carson McCullers and Benjamin Britten. This house became a famous artistic hub. In 1940, Auden rejoined the Episcopal Church, returning to the church he had left at 15. His return to faith was influenced by writers like Charles Williams and Søren Kierkegaard. His new, practical Christianity became a key part of his life.

After Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, Auden offered to return to the UK. He was told that only qualified personnel were needed. In 1941–42, he taught English at the University of Michigan. He was called for the U.S. Army draft in 1942 but was rejected for health reasons. He taught at Swarthmore College from 1942 to 1945.

In 1945, after World War II ended in Europe, he was in Germany. He studied how Allied bombing affected German morale. This experience deeply influenced his later work. When he returned, he settled in Manhattan. He worked as a freelance writer and a visiting professor. In 1946, he became a U.S. citizen.

In 1948, Auden began spending his summers in Europe with Chester Kallman. First, they went to Ischia, Italy. Then, from 1958, he spent summers in Kirchstetten, Austria, where he bought a farmhouse. He was very happy to own a home for the first time. His later poems, written in Austria, include "Thanksgiving for a Habitat" about his Kirchstetten home.

From 1956 to 1961, Auden was a Professor of Poetry at Oxford University. He had to give three lectures each year. This light schedule allowed him to spend winters in New York and summers in Austria. He earned money from readings, lectures, and writing for magazines like The New Yorker.

In 1963, Kallman moved to Athens for winters but still spent summers with Auden in Austria. In February 1972, Auden moved his winter home from New York to Oxford. His old college, Christ Church, gave him a cottage. He spent only one winter in Oxford before he died in 1973.

Auden died at 66 from heart failure in Vienna on September 29, 1973. This was just hours after he gave a poetry reading. He was buried in Kirchstetten, Austria. A memorial stone was placed in Westminster Abbey in London a year later.

Auden's Amazing Poems

Auden published about 400 poems, including seven long ones. His poetry covered many topics and styles. He wrote in modern styles but also used traditional forms like ballads and limericks. His poems ranged from simple songs to deep philosophical thoughts. They covered everything from his own body to atoms and stars.

He also wrote more than 400 essays and reviews about literature, history, politics, and music. He worked on plays with Christopher Isherwood and on opera stories with Chester Kallman. He also collaborated on documentary films.

Auden sometimes changed or removed some of his famous poems from later collections. He said he removed poems he found "boring" or "dishonest." This meant they expressed ideas he didn't truly believe but used for effect. Some rejected poems include "Spain" and "September 1, 1939." His literary helper, Edward Mendelson, says Auden did this because he believed poetry had a powerful effect and didn't want to misuse it.

Early Poems (1922–1939)

Auden started writing poems in 1922, at age 15. His early poems were often like those of 19th-century romantic poets. At 18, he discovered T. S. Eliot and copied his style. He found his own unique voice at 20. His poems from the late 1920s were often short and mysterious. They hinted at themes of loneliness and loss. Twenty of these poems appeared in his first book, Poems (1928).

In 1928, he wrote his first play, Paid on Both Sides. It mixed styles from Icelandic stories with jokes from English school life. This blend of serious and funny, with a dream scene, became a common feature in his later work. This play and 30 short poems appeared in his first published book Poems (1930). These poems were mostly about love, hope, and new beginnings.

A common idea in these early poems is the effect of "family ghosts." This was Auden's term for the strong, hidden ways that past generations affect a person's life. He also explored the difference between natural changes (like evolution) and human changes (like how cultures and people grow).

Developing His Style (1931–1935)

Auden's next big work was The Orators: An English Study (1932). This book, with both poems and prose, was mostly about admiring heroes in personal and political life. His shorter poems became easier to understand. He started using forms from traditional ballads and popular songs. He was also influenced by poets like Dante and Alexander Pope.

During these years, much of his work showed left-wing ideas. He became known as a political poet. However, he was more unsure about revolutionary politics than many people thought. He often wrote about big social changes as a "change of heart." This meant a society moving from fear to love.

His play The Dance of Death (1933) was a political show. His next play, The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935), written with Isherwood, was a modern, political version of a musical. It focused on the idea of social change.

The Ascent of F6 (1937), another play with Isherwood, was partly a satire against imperialism. It also explored Auden's own reasons for being a public political poet. This play included an early version of "Funeral Blues" ("Stop all the clocks"). Auden later rewrote it as a song about lost love. In 1935, he worked on documentary films. He wrote the famous verse for Night Mail. This was part of his effort to create art that was easy to understand and focused on social issues.

Later Early Work (1936–1939)

In 1936, Auden's publisher called a collection of his poems Look, Stranger!. Auden disliked the title. He renamed it On This Island for the 1937 US edition. This book included political poems, love poems, and comic songs.

Auden believed an artist should be like a journalist. He showed this in Letters from Iceland (1937), a travel book with prose and verse written with Louis MacNeice. In 1937, after seeing the Spanish Civil War, he wrote a political poem called Spain. He later removed it from his collected works. Journey to a War (1939) was another travel book with verse and prose. It was written with Isherwood after their visit to the Second Sino-Japanese War. Auden's last work with Isherwood was their play, On the Frontier, an anti-war satire.

Auden's shorter poems now dealt with how fragile personal love can be. He also explored how public life can harm individual lives. In 1938, he wrote dark, ironic poems about people who failed. All these appeared in Another Time (1940). This book also included famous poems like "Musée des Beaux Arts" and "The Unknown Citizen".

His poems for Yeats and Freud were partly anti-heroic. They showed that great things are done not by unique geniuses, but by ordinary people who were "silly like us" (Yeats) or "not clever at all" (Freud). These people became teachers, not just amazing heroes.

Middle Period Poems (1940–1957)

New Themes and Forms

In 1940, Auden wrote a long philosophical poem, "New Year Letter." It appeared in The Double Man (1941). When he returned to the Anglican Church, he began writing abstract poems about religious ideas. Around 1942, as he felt more comfortable with religious themes, his poems became more open. He started using a style called syllabic verse.

Auden's work in this time talked about how artists might use others for their art instead of valuing them as people. It also discussed the importance of keeping promises. From 1942 to 1947, he worked on three long poems in play form. These included "For the Time Being: A Christmas Oratorio" and "The Sea and the Mirror: A Commentary on Shakespeare's The Tempest." Both were published in For the Time Being (1944). He also wrote The Age of Anxiety: A Baroque Eclogue (1947). The first two, with his other new poems, were in his first collected edition, The Collected Poetry of W. H. Auden (1945).

Post-War Work

After finishing The Age of Anxiety in 1946, he focused on shorter poems. Many of these poems described the Italian village where he spent his summers. His next book, Nones (1951), had a Mediterranean feel. A new idea in his work was the "sacred importance" of the human body in everyday life. This included breathing, sleeping, and eating. His poems on these ideas included "In Praise of Limestone" (1948). In 1949, Auden and Kallman wrote the story for Igor Stravinsky's opera The Rake's Progress.

Auden's first prose book was The Enchafèd Flood (1950). It was based on lectures about the image of the sea in romantic literature. Between 1949 and 1954, he worked on a series of seven poems called "Horae Canonicae". These poems looked at history, focusing on the act of murder. While writing this, he also wrote "Bucolics", seven poems about humans and nature. Both series appeared in his next book, The Shield of Achilles (1955).

In 1955–56, Auden wrote poems about "history." He used this term for unique events made by human choices. This was different from "nature," which meant involuntary events like natural processes. These poems included the title poem of his next collection, Homage to Clio (1960).

Later Work (1958–1973)

In the late 1950s, Auden's style became less formal. In 1958, after moving his summer home to Austria, he wrote "Good-bye to the Mezzogiorno." Other poems from this time included "Dichtung und Wahrheit," about love and language. These poems appeared in Homage to Clio (1960). His prose book The Dyer's Hand (1962) collected many of his lectures from Oxford.

Auden started writing haiku and tanka poems after translating some from Dag Hammarskjöld's Markings. A series of 15 poems about his house in Austria, "Thanksgiving for a Habitat," appeared in About the House (1965). In the late 1960s, he wrote strong poems like "River Profile" and two poems looking back at his life. All these were in City Without Walls (1969). His love for Icelandic stories led to his translation of The Elder Edda (1969). One of his later themes was "religionless Christianity," which he learned from Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

A Certain World: A Commonplace Book (1970) was like a self-portrait. It was made of his favorite quotes with his comments, arranged alphabetically. His last prose book was Forewords and Afterwords (1973). His last poetry books, Epistle to a Godson (1972) and Thank You, Fog (published after he died, 1974), included poems about language, philosophy, and getting older. His last finished poem was "Archaeology," about traditions and timelessness.

Auden's Impact and Fame

Auden's place in modern literature has been much discussed. Many critics in the 1930s thought he was less important than poets like Yeats and Eliot. However, some, especially in recent years, believe he was the best of the three. Opinions varied greatly. Some called him "a complete wash-out," while others said he was "its undisputed master." Joseph Brodsky even said Auden had "the greatest mind of the twentieth century."

When Auden's first book, Poems (1930), came out, some critics were very positive. But others, like John Sparrow, thought his early work showed wrong goals for poets.

Auden's sharp, ironic style in the 1930s was copied by many younger poets. He was seen as the leader of an "Auden group" with his friends Stephen Spender, Cecil Day-Lewis, and Louis MacNeice. Some people made fun of them, calling them "Macspaunday." Auden's political plays and poems, like "Spain," gave him a reputation as a political poet. This was different from Eliot. But this political stance caused strong reactions. Some called his work "liberal, democratic, and humane," while others said he used a "popularizing trick" to present left-wing views that were only for middle-class people.

Auden's move to America in 1939 was debated in Britain. Some saw it as a betrayal. But his supporters, like Geoffrey Grigson, said Auden "arches over all." Books like Auden and After (1942) and The Auden Generation (1977) showed his importance.

In the U.S., Auden's calm, ironic style became very influential from the late 1930s. John Ashbery remembered that in the 1940s, Auden "was the modern poet." His influence was so widespread that the wild style of the Beat Generation was partly a reaction against it. From the 1940s to the 1960s, many critics felt Auden's work had declined.

The first full study of Auden was Richard Hoggart's Auden: An Introductory Essay (1951). It said Auden's work was a "civilising force." Monroe K. Spears' The Poetry of W. H. Auden (1963) called his poetry "unique in our time."

Auden was suggested for the Nobel Prize in Literature several times in the 1960s. By the time he died in 1973, he was seen as a respected older writer. A memorial stone for him was placed in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey in 1974. The Encyclopædia Britannica says that by 1965, Auden was seen as Eliot's successor, just as Eliot had followed Yeats. British critics often liked his early work best, while American critics preferred his middle and later work.

Many critics and poets believe Auden's fame did not fade after his death. His later writing strongly influenced younger American poets. Later evaluations describe him as "arguably the [20th] century's greatest poet."

Public interest in Auden's work greatly increased after his poem "Funeral Blues" was read in the movie Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994). A small book of his poems then sold over 275,000 copies. An excerpt from "As I walked out one evening" was recited in the film Before Sunrise (1995). After September 11, 2001, his 1939 poem "September 1, 1939" was widely shared. In 2007, his 100th birthday was celebrated with readings and tributes.

Overall, Auden's poetry was known for its great style and skill. It explored politics, morals, love, and religion, and showed a wide range of tones, forms, and topics.

Memorials for Auden include stones and plaques in Westminster Abbey, at his birthplace in York, near his home in Birmingham, and in Oxford. There are also plaques in Brooklyn Heights and New York. His study in Kirchstetten, Austria, is open to the public.

Published Works

The list below includes the books of poems and essays that Auden prepared during his lifetime.

- Poems (London, 1930; includes poems and Paid on Both Sides: A Charade).

- The Orators: An English Study (London, 1932, verse and prose).

- The Dance of Death (London, 1933, play).

- Poems (New York, 1934; contains Poems [1933 edition], The Orators [1932 edition], and The Dance of Death).

- The Dog Beneath the Skin (London, New York, 1935; play, with Christopher Isherwood).

- The Ascent of F6 (London, 1936; play, with Christopher Isherwood).

- Look, Stranger! (London, 1936, poems; US edn., On This Island, New York, 1937).

- Letters from Iceland (London, New York, 1937; verse and prose, with Louis MacNeice).

- On the Frontier (London, 1938; play, with Christopher Isherwood).

- Journey to a War (London, New York, 1939; verse and prose, with Christopher Isherwood).

- Another Time (London, New York 1940; poetry).

- The Double Man (New York, 1941, poems; UK edn., New Year Letter, London, 1941).

- For the Time Being (New York, 1944; London, 1945; two long poems: "The Sea and the Mirror: A Commentary on Shakespeare's The Tempest" and "For the Time Being: A Christmas Oratorio").

- The Collected Poetry of W. H. Auden (New York, 1945; includes new poems).

- The Age of Anxiety: A Baroque Eclogue (New York, 1947; won the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry).

- Collected Shorter Poems, 1930–1944 (London, 1950; similar to 1945 Collected Poetry).

- The Enchafèd Flood (New York, 1950; prose).

- Nones (New York, 1951; poems).

- The Shield of Achilles (New York, London, 1955; poems; won the 1956 National Book Award for Poetry).

- Homage to Clio (New York, London, 1960; poems).

- The Dyer's Hand (New York, 1962; essays).

- About the House (New York, London, 1965; poems).

- Collected Shorter Poems 1927–1957 (London, 1966).

- Collected Longer Poems (London, 1968).

- Secondary Worlds (London, New York, 1969; prose).

- City Without Walls and Other Poems (London, New York, 1969).

- A Certain World: A Commonplace Book (New York, London, 1970; quotations with commentary).

- Epistle to a Godson and Other Poems (London, New York, 1972).

- Forewords and Afterwords (New York, London, 1973; essays).

- Thank You, Fog: Last Poems (London, New York, 1974).

- Coal Face (1935, closing chorus for documentary).

- Night Mail (1936, narrative for documentary).

- Paul Bunyan (1941, story for operetta by Benjamin Britten).

- The Rake's Progress (1951, with Chester Kallman, story for an opera by Igor Stravinsky).

- Elegy for Young Lovers (1956, with Chester Kallman, story for an opera by Hans Werner Henze).

- The Bassarids (1961, with Chester Kallman, story for an opera by Hans Werner Henze).

- Runner (1962, documentary film narrative).

- Love's Labour's Lost (1973, with Chester Kallman, story for an opera by Nicolas Nabokov).

- Our Hunting Fathers (1936, song cycle for Benjamin Britten).

- Hymn to St Cecilia (1942, choral piece composed by Benjamin Britten).

- An Evening of Elizabethan Verse and its Music (1954 recording; Auden spoke the verse).

- The Play of Daniel (1958, verse narration for a production).

Images for kids

-

Christopher Isherwood (left) and W. H. Auden (right) photographed by Carl Van Vechten, 1939

See also

In Spanish: Wystan Hugh Auden para niños

In Spanish: Wystan Hugh Auden para niños