Spirituals facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Spiritual |

|

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | African Americans |

| Derivative forms |

|

| Fusion genres | |

| CCM | |

Spirituals are a type of Christian music created by African Americans. This music blends African culture with the difficult experiences of slavery. Spirituals include "sing songs," work songs, and plantation songs. Over time, they led to new music styles like the blues and gospel.

In the 1800s, the word "spirituals" covered all these folk songs. Many spirituals were based on Bible stories. They also described the extreme hardships faced by enslaved African Americans from the 1600s to the 1860s.

Before the American Civil War ended in 1865, spirituals were passed down orally. People memorized Bible stories and turned them into songs. After slavery ended, the words to spirituals were written down. Groups like the Fisk Jubilee Singers, started in 1871, made spirituals famous around the world.

At first, major recording studios only recorded white musicians singing spirituals. This changed in 1920 with the success of Mamie Smith. Starting in the 1920s, more people heard spirituals and their new music styles through commercial recordings.

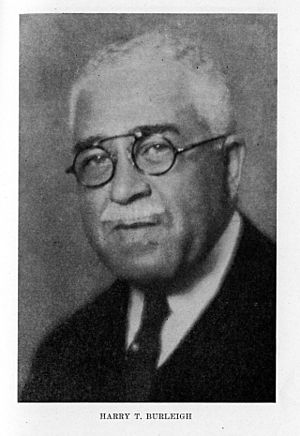

Black composers, like Harry Burleigh and R. Nathaniel Dett, used their classical music training to create new versions of spirituals for concerts. Even though spirituals began with enslaved people, they became known as the first "signature" music of the United States.

Contents

What are Spirituals?

The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians is a huge book about music. It describes "spirituals" as a "type of sacred song created by and for African Americans." These songs started as an oral tradition, meaning they were sung and passed down, not written. They became a clear music style by the early 1800s.

The term "spirituals" was used in the 1800s for religious songs made by enslaved Africans in America. The first book of slave songs called them spirituals.

Today, in music studies, the single term "spirituals" is often used. The Library of Congress uses "African American Spirituals" for its official entries. They also say, "A spiritual is a type of religious folksong most closely linked to the enslavement of African people in the American South." These songs grew popular in the late 1700s, leading up to the end of slavery in the 1860s.

The Story Behind Spirituals

The transatlantic slave trade forced millions of Africans to move across the ocean. This happened over 400 years. From 1501 to 1867, about 12.5 million Africans were kidnapped and forced into slavery. Most came from West Africa and were sent to the Americas.

About 6% of all enslaved Africans brought by the slave trade arrived in the United States. Most of these came from the West African slave coast. After the U.S. outlawed the international slave trade in 1808, a domestic slave trade began. This trade lasted until the Civil War. It tore apart many African American families.

Slavery in the U.S. was different from other places. In the U.S., the enslaved population grew naturally over time. By 1850, most enslaved African Americans were third, fourth, or fifth-generation Americans. This meant they were born in America, unlike many enslaved people in other regions who were born in Africa.

Slavery ended in the U.S. with the Civil War in 1865. The first enslaved Africans arrived in what is now South Carolina in 1526. They were the first to rebel against slavery. In 1619, another ship brought twenty people from the Kingdom of Kongo to America. The Kongo Kingdom was a large, Christian kingdom in Africa.

The descendants of enslaved people in the Gullah community, from Sierra Leone, were unique. They lived on islands off South Carolina and were more isolated. Their spirituals are sung in a special language. This language was influenced by African-American Vernacular English and African languages like Akan, Yoruba, and Igbo.

How Spirituals Helped Enslaved People

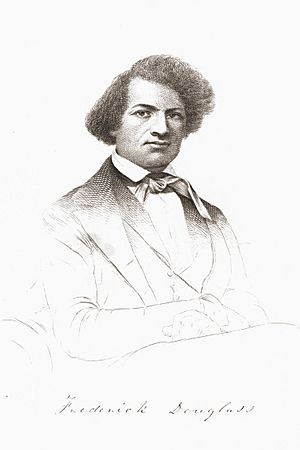

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) was a famous speaker and former slave. In his 1845 book, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, he described slave songs. He said they told a story "beyond my feeble comprehension." He felt they were "the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish." These songs made him hate slavery even more. Douglass's book was very important in the early movement to end slavery.

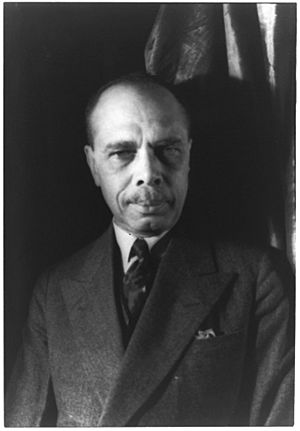

W. E. B. Du Bois called slave songs "Sorrow songs" in his 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk.

Hansonia Caldwell, a music expert, said spirituals "sustained Africans when they were enslaved." She called them "code songs." For example, "Steal Away" could announce meetings. "Follow the Drinkin' Gourd" might describe a path to escape. "Go Down Moses" referred to Harriet Tubman, who was nicknamed Moses. When people heard that song, they knew she was coming to help them.

Caldwell explained that spirituals were like an "omnibus term" because they included many types of songs. People sang them while working in the fields. In church, they became gospel songs. In the fields, they developed into the blues.

The Library of Congress stated in 2016 that "The African American spiritual... constitutes one of the largest and most significant forms of American folksong."

Spirituals were first passed down by singing. But in 1867, the first collection, "Slave Songbook," was published. One of the compilers, William Francis Allen, said it was hard to write down spirituals. He said the unique voices and "delicate variations" of African American singers could not be "reproduced on paper." He described how a lead singer would start a verse, often making it up, and others would join in the chorus.

In their 1925 book, The Books of American Negro Spirituals, James Weldon Johnson and Grace Nail Johnson wrote that spirituals are "purely and solely the creation" of African Americans. They called them "America's only type of folk music." They noted that the song makers used the words they knew to share Bible stories and other facts through song. James Weldon Johnson was a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Arthur C. Jones started "The Spirituals Project" at the University of Denver. Its goal is to save and share the "music and teachings of the sacred folk songs called spirituals." These songs were created by enslaved African Americans. They became the first "signature" music of the United States. Enslaved people were often not allowed to speak their native languages. They learned Christianity and used the words they knew to turn Bible stories into songs.

African Roots of Spirituals

J.H. Kwabena Nketia, a leading expert on African music, said in 1973 that there is a strong connection between African and African American music.

Enslaved African Americans in the South used their native rhythms and African heritage. A 2012 PBS interview explained that spirituals were religious folk songs. They were often based on Bible stories and passed down through generations of enslaved people.

Walter Pitts' 1996 book said that spirituals are a unique music form. They came from the religious experiences of enslaved Africans and their descendants in the U.S. Pitts believed they were a mix of African and European music and religion.

Uzee Brown, Jr. said in a 2012 PBS interview that spirituals were "survival tools for the African slave." He noted that African slaves survived because they "sang through many of their problems." They created their own "way of communicating." Enslaved people brought new instruments to America, like the bones and early versions of the banjo. They also brought traditions of storytelling.

The use of "complex rhythms" and "polyrhythms" from West Africa shows how important African music was in creating spirituals.

Religion in Daily Life

In the beliefs of enslaved people, the "material and the spiritual are part of an intrinsic unity." This means music, religion, and daily life were all connected in spirituals. Through these songs, religious ideas became part of everyday activities. Spirituals helped protect African American religion from being taken over. This kept a "sacred space of resistance."

A 2015 article in the Journal of Black Studies noted that spirituals were sung as "rowing songs, field songs, work songs, and social songs," not just in church. The article explained that spirituals used "metonymy" (using related words to change meaning). This allowed them to teach about both physical and spiritual freedom at the same time. An example is the spiritual "Steal Away to Jesus."

William Eleazar Barton wrote in Old Plantation Hymns that African American hymns rarely mentioned the Bible as their source. They preferred "heart religion" over "book religion." Barton observed that they appealed to a personal "revelation from the Lord." He gave examples like "We're Some of the Praying People" and "Wear a starry crown." These songs often had a "threefold repetition and a concluding line" and the "familiar swing and syncopation" of African American music.

Spirituals were not just different versions of hymns. They were new creations with new melodies, changed words, and unique styles. This made them distinctly African-American.

The First Great Awakening, a series of Christian revivals in the 1730s and 1740s, led many enslaved people to become Christians. Northern Baptist and Methodist preachers converted African Americans. In some places, African Americans became deacons in Christian communities. From 1800 to 1825, enslaved people heard religious music at camp meetings. As African religious traditions faded in America, more African Americans converted to Christianity.

Bible Stories in Spirituals

By the 1600s, enslaved Africans knew Bible stories like Moses and Daniel. They saw their own lives reflected in these stories. An Africanized form of Christianity grew among enslaved people. Spirituals became a way to show their new faith, their sadness, and their hopes.

As Africans learned Bible stories, they saw connections to their own experiences. The story of the Jews being exiled and held captive in Babylon felt similar to their own captivity.

Christian spirituals use symbols from the Bible. For example, Moses and Israel's Exodus from Egypt appear in songs like "Michael Row the Boat Ashore". Spirituals often had a double meaning. They shared Christian ideas while also talking about the hardships of slavery.

The Jordan River in African American religious songs was a symbol. It could mean the border between this world and the next. It could also mean traveling north to freedom or moving from slavery to a free life.

Spiritual music naturally used syncopation, which is a "ragged" or off-beat rhythm. Songs were played on instruments inspired by African music.

Collecting Spirituals

African-American spirituals are linked to plantation songs, slave songs, freedom songs, and songs of the Underground Railroad. They were passed down orally until the end of the American Civil War. After the war, many spirituals were collected and saved as folk songs.

The first collection of Negro spirituals was published in 1867, two years after the war. It was called Slave Songs of the United States. Three abolitionists from the North—Charles Pickard Ware, Lucy McKim Garrison, and William Francis Allen—put it together. Most of the songs in the book were gathered directly from African Americans.

By the 1830s, "plantation songs" and "Negro melodies" were very popular. Some "fake" songs were created for more "sentimental tastes." The authors noted that songs like "Long time ago" were borrowed from African-American songs. There was new interest in these songs through the Port Royal Experiment (1861). In this experiment, newly freed African Americans successfully ran plantations on Port Royal Island. Northern abolitionists, teachers, and doctors came to help. The authors noted that by 1867, the first seven spirituals in their collection were "regularly sung at church."

In 1869, Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson published his memoir, Army Life in a Black Regiment. He commanded the first African-American regiment in the Civil War. He admired the former slaves in his regiment. He wrote down some of the spirituals he heard in camp. He noted that "Almost all their songs were thoroughly religious... and were in a minor key."

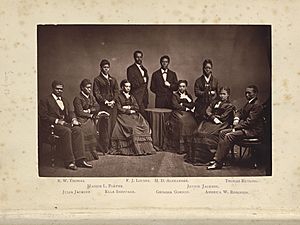

Starting in 1871, the Fisk Jubilee Singers began touring. This made spirituals popular as concert music. By 1872, the Jubilee Singers were publishing their own songbooks, including "The Gospel Train".

Reverend Alexander Reid heard the Fisk Jubilee Singers perform in 1871. He suggested they add songs he heard from an enslaved couple, Wallace Willis and his wife Minerva. They sang "their favorite plantation songs" in Oklahoma. Reid gave the Jubilee Singers the words to songs like "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" and "Steal Away To Jesus". The Jubilee Singers helped make Willis's songs famous.

Spirituals Become Popular

Fisk Jubilee Singers

The original Fisk Jubilee Singers were a touring group of nine students from the new Fisk school in Nashville, Tennessee. They sang a cappella (without instruments) from 1871 to 1878. They made Negro spirituals very popular. The name "jubilee" came from the "year of jubilee" in the Old Testament, a time when slaves were freed.

Fisk University was founded in 1866, shortly after the Civil War. The Fisk Jubilee Singers started their first tour on October 6, 1871, to raise money for the school. At first, their audiences were small. But by 1872, they performed at Boston's World Peace Festival and at the White House. In 1873, they toured Europe.

In their early days, the Jubilee Singers did not sing slave songs. Ella Sheppard, one of the original singers, explained that these songs "were sacred to our parents." She said it took many months for their hearts to open to these songs' "wonderful beauty and power." Eventually, these songs became part of their performances.

The original Singers stopped performing in 1878. But in 1890, Ella Sheppard returned to Fisk. She began coaching new jubilee singers, including John Wesley Work Jr.. In 1899, Fisk University formed a new mixed choir to tour. This choir became too expensive, so it was replaced by John Work II's male quartet. This quartet became very famous and made many best-selling recordings. John Work Jr. spent 30 years at Fisk University, collecting and sharing the "jubilee songcraft." In 1901, he published New Jubilee Songs as Sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers with his brother.

From 1890 to 1919, African Americans made important contributions to the early recording industry. The Fisk Jubilee Singers and others made many recordings.

Hampton Singers

In 1873, the Hampton Singers formed at what is now Hampton University in Virginia. They were the first group to compete with the Jubilee Singers. With Robert Nathaniel Dett as their conductor until 1933, the Hampton Singers became famous worldwide.

Tuskegee Institute Quartet

The first official a cappella Tuskegee Quartet was started in 1884 by Booker T. Washington. He was the founder of the Tuskegee Institute. Washington believed everyone at their weekly religious services should sing African American spirituals. The Quartet was formed to "promote the interest of Tuskegee Institute." A new quartet formed in 1909 and toured until the 1940s. Like the Fisk Jubilee Singers, they sang spirituals in a changed, harmonized style.

Concert Spirituals

African American composers like Harry Burleigh, R. Nathaniel Dett, and William Dawson used their classical music training to create new versions of spirituals for concert stages. They brought spirituals to formal concerts. They also guided the next generation of professional spirituals musicians starting in the early 1900s.

Harry Burleigh (1866–1949) was an African-American classical composer and singer. He performed in many concerts. In 1929, he published Jubilee Songs of the United States. This made spirituals available for solo concert singers as "art songs" for the first time. Burleigh arranged spirituals in a classical style. He also introduced classical artists like Antonín Dvořák to African-American spirituals. Some believe Dvořák was inspired by spirituals for his Symphony From the New World. Burleigh coached African-American solo singers like Marian Anderson. Others, like Roland Hayes and Paul Robeson, continued his work.

R. Nathaniel Dett (1882–1943) is known for his arrangements. He combined the music of European Romantic composers with African-American spirituals. In 1918, he said, "We have this wonderful store of folk music—the melodies of an enslaved people." He believed spirituals should be used in "choral form, in lyric and operatic works, in concertos and suites." R. Nathaniel Dett mentored Edward Boatner (1898–1981). Boatner was an African American composer who wrote many popular concert arrangements of spirituals. Boatner and Willa A. Townsend published Spirituals triumphant old and new in 1927. Boatner believed in keeping spirituals authentic but also liked new, polished arrangements.

William L. Dawson (1876–1938) was a composer and choir director. His 1934 Negro Folk Symphony was first performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra. He revised it in 1952, adding African rhythms after a trip to West Africa. One of his most famous spirituals is "Ezekiel Saw the Wheel".

Spirituals Today

The Fisk Jubilee Singers are still popular today. They perform live in places like the Grand Ole Opry House in Nashville, Tennessee. In 2019, Tazewell Thompson created an a cappella musical called Jubilee, honoring the Fisk Jubilee Singers.

Spirituals are still very important, especially in small Black churches in the deep South.

In the late 1900s, spirituals became popular again. Composers and music directors like Moses Hogan and Brazeal Dennard greatly influenced this trend.

Arthur Jones started "The Spirituals Project" at the University of Denver in 1999. It aims to keep the message and meaning of these songs alive.

Everett McCorvey founded The American Spiritual Ensemble in 1995. This group of about two dozen professional singers performs spirituals in the U.S. and other countries. They have released several CDs and are featured in a public broadcasting documentary.

Music Style of Spirituals

Spirituals are known for their excellent blending of voices, timing, and pitch.

Originally, spirituals were sung without instruments. They were "monophonic," meaning everyone sang the same melody. Sometimes the tempo would slow down, especially in "sorrow songs," to show the beauty of the voices.

Songs might include a "solo call and unison response." They can also have "overlapping layers" and high-pitched humming.

Spirituals get their style from African music, Christian hymns, work songs, field holler, and Islamic music. They were sung as lullabies and play songs. Some were changed to be work songs.

Black spirituals use "microtonally flatted notes," syncopation, and counter-rhythms with handclapping. The singers' voices are strong, with shouting, exclamations of "Glory!", and rough, high-pitched tones.

Many rhythms and sounds in spirituals come from African sources. This includes the use of the pentatonic scale (like the black keys on a piano).

In his 1954 book Studies in African Music, Arthur Morris Jones said that in African music, complex rhythms were central. This was like how harmonies were important in European music. Jones explained that drums are the best way to make rhythms. But rhythms can also be made by hand-clapping, stick-beating, rattles, and pounding.

Over time, a "formal concert tradition" for spirituals developed. This included the work of the Hampton Singers under composer R. Nathaniel Dett.

In the 1900s, composers like Moses Hogan and Roland Carter changed a cappella arrangements of spirituals for choirs. They moved beyond the songs' traditional folk roots.

Sorrow Songs

W. E. B. Du Bois called slave songs "Sorrow Songs" in his 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk. Sorrow songs are spirituals like "Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child" and "Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen". These songs are deep and sad, sung at a slower pace.

Jubilee Songs

The Fisk Jubilee Singers were so successful that other groups formed to sing similar music. Over time, "jubilee" also referred to other groups who sang the original group's songs. In the early 1900s, jubilee singers also sang gospel music and hymns. Examples include the Norfolk Jubilee Quartet and the Tuskegee Institute Singers.

Jubilee songs, also called "camp meeting songs," like "Fare Ye Well" and "Rocky my soul in the bosom of Abraham" are fast-paced and rhythmic. Spiritual songs that looked forward to future happiness or freedom were often called 'jubilees'.

In some churches, like Pentecostal churches in New Orleans in the 1910s and 1920s, there was no organ or choir. The music was louder and more joyful. It included fast spirituals called "jubilees." They used drums, cymbals, tambourines, and steel triangles. Everyone sang, clapped, and stomped their feet. They had a strong rhythm from slavery days.

Freedom Songs

Frederick Douglass, a former slave and abolitionist, said slave songs made him realize how terrible slavery was. He said, "Those songs still follow me, to deepen my hatred of slavery."

A 2017 PBS Newshour segment said that "Wade in the Water" is believed to be one of the songs linked to the Underground Railroad. The Underground Railroad was a secret network used by enslaved people to escape to freedom. "Wade in the Water" might have warned slaves to get into the water to hide their scent from bloodhounds used by slave owners.

Jones described how existing spirituals were secretly used during the Underground Railroad. This was one of many ways people fought for freedom. Coded words could be hidden in the call-and-response parts of songs. Only those who knew the secret message would understand.

A project by Maryland Public Television said that many slave songs had "secret meanings." They could be used to signal many things. Some songs were believed to contain instructions for escaping slaves on how to avoid capture and find their way to freedom. Other spirituals thought to have coded messages include "The Gospel Train" and "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot".

A 1953 article by Sterling Brown noted that some scholars believed when enslaved people sang of freedom, they only meant freedom from sin. But Brown argued that for an enslaved person, freedom also meant freedom from slavery. When they sang, "I been rebuked, I been scorned; done had a hard time sho's you bawn," they meant both spiritual and physical freedom. Brown mentioned that Douglass said "Canaan" stood for Canada. He also said songs were like "grapevines for communications." Harriet Tubman, called the Moses of her people, said "Go Down Moses" was forbidden in slave states, but people sang it anyway.

A 2016 Library of Congress article said that Freedom songs and protest songs, like Bob Marley's "Redemption Song", were based on African American spirituals. These songs became the music for calls for democracy around the world. Many freedom songs, such as "Oh, Freedom!" and "Eyes on the Prize," that defined the Civil rights movement (1954–1968) came from early African American spirituals. Some, like "We Shall Overcome," combined the gospel hymn "I'll Overcome Someday" with the spiritual "I'll Be all right."

Work Songs

In the 1927 book The American Songbag, Carl Sandburg wrote that "Ain' go'n' to study war no mo'" was a spiritual used as a work song. He said that as singers worked, they would add lines from other spirituals. The rhythm was steady and flowing. It was a work song-spiritual.

Field Hollers

Field holler music was an early form of African American music from the 1800s. Field hollers were cries and hollers from enslaved people and later sharecroppers working in fields, prison chain gangs, or railway gangs. They were the start of the call-and-response style in African American spirituals and gospel music. They also led to the blues, rhythm and blues, jazz, and African American music in general.

Music Styles That Came From Spirituals

Blues and gospel music are music styles that grew out of African American spirituals.

The Blues

In the early 1960s, Blues People by Amiri Baraka told the history of African Americans through their music, starting with spirituals and moving to the blues.

The blues style began in the 1860s in the Deep South. These states relied heavily on slave labor on plantations. The blues were developed by generations of enslaved African Americans. They started as "unaccompanied work-songs of the plantation culture." The roots of the blues can be traced back to West African music. Elements like the "leader-and-chorus" style come from there. The blues became one of the most recorded types of traditional music. Since the early 1960s, it has been a major influence on Western popular music.

On August 10, 1920, Mamie Smith's recording of "Crazy Blues" became a huge success. This opened the door for commercial record companies to record music for an African American audience. Before this, recording companies mainly featured non-African American musicians playing African-American music. Mamie Smith's band, the Jazz Hounds, played lively, improvised music. This was a refreshing change from the more formal versions of the blues played by white artists in the 1910s.

A 1976 book, Stomping the Blues by Albert Murray, said that the mix of Christianity and African-American spirituals happened only in the United States. Africans who became Christian in other parts of the world, even in the Caribbean, did not develop this specific music form.

Gospel Songs

Sacred music includes both spirituals and gospel music. Gospel music "originated in the black church and has become a globally recognized genre." At first, gospel music was a key part of worship services. Now, it is also sold commercially and uses modern sounds while still sharing spiritual ideas.

Famous gospel singer Mahalia Jackson (1911–1972) was a strong supporter of gospel music. She said, "Blues are the songs of despair. Gospel songs are the songs of hope." She believed gospel music offered a cure for problems, while the blues left you with nothing. Horace Clarence Boyer traced gospel music's start to Pentecostal churches in the Deep South in 1906. Through the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to the North, especially in the 1930s, gospel songs became part of popular American culture. Gospel music was most popular from 1945 to 1955, known as the "Golden Age of Gospel."

Gospel Quartets, like the Golden Jubilee Quartet and the Golden Gate Quartet, changed the style of spirituals. They used new harmonies and complex arrangements. An example is their performance of "Oh, Jonah!" The Golden Gate Quartet performed at Carnegie Hall in the late 1930s. Zora Neale Hurston, in her 1938 book The Sanctified Church, criticized the "Glee Club style" of groups like the Fisk Jubilee Singers in the 1930s. She felt they used "musicians' tricks" that were not true to the original African American spirituals. She believed authentic spirituals could only be found in the "unfashionable Negro church."

White Spirituals

In his 1938 book, White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands, George Pullen Jackson wrote about white spirituals. These differed from African American spirituals. Jackson argued that African-American spirituals used many words and melodies from white hymns and spiritual songs. He used the term "spirituals" for a wider range of folk hymns. The term has also been used for later arrangements of spirituals into more standard European-American hymn styles. It also includes post-emancipation songs that sound similar to the original African American spirituals.

Islamic Influence

Historian Sylviane Diouf and music expert Gerhard Kubik believe Islamic music influenced spirituals. Diouf noticed a strong similarity between the Adhan (the Islamic call to prayer) and 1800s field holler music. Both have similar lyrics praising God, melodies, and vocal styles. She thinks field holler music came from African Muslim slaves, who made up about 30% of African slaves in America.

Kubik noted that the singing style of many blues singers, with its wavy tones, comes from West Africa. This region had contact with the Arabic-Islamic world since the 600s and 700s. There was a lot of musical exchange between North Africa and West Africa.

There was a difference in music between mostly Muslim slaves from the Sahel region and mostly non-Muslim slaves from coastal West Africa and Central Africa. Sahelian Muslim slaves preferred wind and string instruments and solo singing. Non-Muslim slaves preferred drums and group chants. Plantation owners feared revolts, so they banned drums and group chants. But they allowed Sahelian slaves to sing and play wind and string instruments, which seemed less threatening. Muslim African slaves introduced instruments like ancestors of the banjo. Many were pressured to become Christian. But Sahelian slaves were allowed to keep their music traditions, adapting their skills to instruments like the fiddle and guitar. Some even performed at balls for slave owners, helping their music spread across the South.

See also

In Spanish: Espiritual para niños

In Spanish: Espiritual para niños

- African-American music

- Deep River Boys

- Gospel music

- History of slavery in the United States

- Original Nashville Students

- Religious music

- Songs of the Underground Railroad

Notable Songs

These are some famous spirituals:

- All God's Chillun Got Wings

- Bosom of Abraham

- Children, Go Where I Send Thee

- Deep River

- Dem Bones

- Didn't It Rain

- Do Lord Remember Me

- Down by the Riverside

- Down in the River to Pray

- Every Time I Feel the Spirit

- Ezekiel Saw the Wheel

- Follow the Drinkin' Gourd

- Go Down Moses

- Go Tell It on the Mountain

- Golden Slippers

- Gospel Plow

- The Gospel Train

- He's Got the Whole World in His Hands

- I Shall Not Be Moved

- I'm So Glad

- Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho

- Kumbaya

- Lord, I Want to Be a Christian

- Michael Row the Boat Ashore

- Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen

- Roll, Jordan, Roll

- Satan, Your Kingdom Must Come Down

- Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child

- Song of the Free

- Steal Away

- Swing Low, Sweet Chariot

- There Is a Balm in Gilead

- This Little Light of Mine

- Wade in the Water

- We Are Climbing Jacob's Ladder

- Were You There

- We Shall Overcome

- When the Chariot Comes

- When the Saints Go Marching In