James Weldon Johnson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

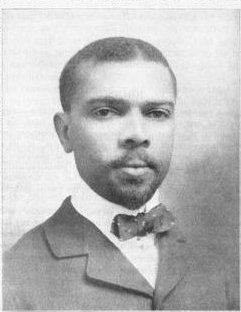

James Weldon Johnson

|

|

|---|---|

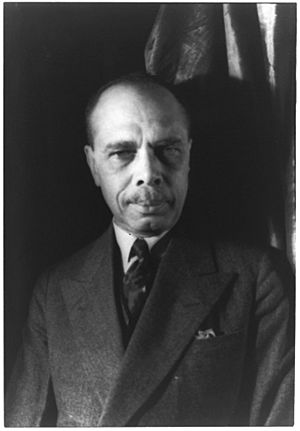

Photographed by Carl Van Vechten, 1932

|

|

| Born | June 17, 1871 Jacksonville, Florida |

| Died | June 26, 1938 (aged 67) Wiscasset, Maine |

| Resting place | Green-Wood Cemetery, New York City |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | English |

| Alma mater | Atlanta University |

| Period | Harlem Renaissance (1891–1938) |

| Subject | Civil rights |

| Notable works | "Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing", The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, God's Trombones, Along This Way |

| Notable awards | Spingarn Medal from NAACP, Harmon Gold Award |

| Spouse | Grace Nail Johnson |

James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871 – June 26, 1938) was an important American writer and civil rights activist. He was married to Grace Nail Johnson, who was also a civil rights activist.

Johnson was a key leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He started working there in 1917. In 1920, he became the executive secretary, which meant he was in charge of the organization's daily work. He held this important role until 1930.

He became well-known as a writer during the Harlem Renaissance. This was a time when African American art and culture greatly grew in the 1920s. Johnson was famous for his poems, a novel, and collections of poems and spirituals (religious songs) from Black culture. He wrote the words for "Lift Every Voice and Sing". This song later became known as the Negro National Anthem. His younger brother, J. Rosamond Johnson, wrote the music.

President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Johnson as a U.S. consul (a diplomat who helps citizens abroad) in Venezuela and Nicaragua. He served in these roles from 1906 to 1913. In 1934, he made history as the first African American professor hired at New York University. Later, he taught creative writing at Fisk University, a university mainly for Black students.

Contents

Life Story

Johnson was born in 1871 in Jacksonville, Florida. His mother, Helen Louise Dillet, was from the Bahamas. His father was also named James Johnson. His great-grandmother had escaped from Haiti in 1802 during a revolution. She settled in the Bahamas. Her son, Stephen Dillet, became the first Black man elected to the Bahamian government in 1833.

James's brother, J. Rosamond Johnson, became a famous composer. Their mother, a musician and teacher, taught them a lot about English literature and music. At 16, Johnson went to Atlanta University, a historically black college. He graduated in 1894.

His father, a preacher and headwaiter at a fancy hotel, inspired James to have a professional career. Johnson felt it was his duty to use his education to help Black people. He was also a proud member of the Phi Beta Sigma fraternity.

Johnson and his brother Rosamond moved to New York City. They were part of the Great Migration, when many Black people moved from the South to Northern cities. They worked together writing songs and had success on Broadway in the early 1900s. For the next 40 years, Johnson worked in education, as a diplomat, and as a civil rights activist.

In 1910, Johnson married Grace Nail. She was a well-educated New Yorker. Grace later worked with her husband on writing movie scripts. After returning from Nicaragua, Johnson became very involved in the Harlem Renaissance. He wrote his own poetry and helped other Black artists and writers. His influence and new style of poetry made him a leading voice in the Harlem Renaissance.

Fighting for Civil Rights

Johnson became very active in the fight for civil rights. He especially worked to pass the federal Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill. This bill aimed to stop lynchings (mob killings) in the Southern states, where local governments often did not punish those responsible. He spoke at a big meeting about lynching in 1919.

Johnson started as a field secretary for the NAACP in 1917. He quickly became one of the most successful leaders in the organization. In 1920, he wrote a report about the U.S. occupation of Haiti. He described how the U.S. military caused economic problems, forced labor, and violence there. This report encouraged many African Americans to demand that U.S. troops leave Haiti. The U.S. finally ended its occupation in 1934.

In 1920, Johnson became the first Black executive secretary of the NAACP. He helped the NAACP grow by organizing many new local groups in the South. During this time, the NAACP often challenged laws that stopped African Americans from voting. These laws included poll taxes (fees to vote), literacy tests (reading tests), and white primaries (only white people could vote in primary elections).

While at Atlanta University, Johnson was known as a powerful speaker. In 1895, he started and edited the Daily American newspaper. This newspaper covered political and racial issues. It was a time when Southern states were passing Jim Crow laws to create racial segregation and stop Black people from voting. These early efforts showed Johnson's long commitment to activism.

In 1914, Johnson became an editor for the New York Age. This was an important African-American newspaper in New York City. His writing for the Age showed his great political skill.

In 1916, Johnson began working as an organizer for the NAACP. He helped build and restart local chapters. He organized large protests against race riots in Northern cities and the frequent lynchings in the South after World War I. On July 28, 1917, he organized a silent protest parade of over 10,000 African Americans down Fifth Avenue in New York City.

After World War I, there was a lot of tension as veterans returned and looked for jobs. In 1919, Johnson named the period the "Red Summer". This was because of the white racial violence against Black people that happened in many cities across the North and Midwest. He organized peaceful protests against this violence.

Johnson traveled to Haiti to see what was happening there. U.S. Marines had occupied the island since 1915. In 1920, Johnson published articles in The Nation magazine describing the American occupation as cruel. He suggested ways to help Haiti's economy and society. These articles were later put into a book called Self-Determining Haiti.

As executive secretary of the NAACP from 1920 to 1930, Johnson worked hard for the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill of 1921. The House of Representatives easily passed the bill, but white Southern politicians in the Senate repeatedly blocked it.

Throughout the 1920s, Johnson supported and promoted the Harlem Renaissance. He helped young Black authors get their work published. Before he died in 1938, Johnson also supported Ignatz Waghalter, a Jewish composer who escaped the Nazis. Waghalter wanted to create a classical orchestra of African-American musicians.

Teacher and Lawyer

In 1891, after his first year at Atlanta University, Johnson taught in a rural area of Georgia. He taught the children and grandchildren of formerly enslaved people. He said those three months taught him a lot about life. Johnson graduated from Atlanta University in 1894.

After college, he returned to Jacksonville. He taught at Stanton, a school for African-American students. Public schools were separated by race back then. In 1906, at 35, he became the principal. Even as principal, Johnson was paid less than half of what white principals earned. He improved Black education by adding the ninth and tenth grades to the school. He later left this job to follow other goals.

While teaching, Johnson also studied law. In 1897, he became the first African American to pass the Florida Bar Exam since the Reconstruction era ended. He was also the first Black person in Duval County, Florida to try to become a lawyer. He had to take a two-hour oral test in front of three lawyers and a judge. Johnson used his legal knowledge often during his years as a civil rights activist with the NAACP.

In 1930, at age 59, Johnson returned to teaching after his many years leading the NAACP. He accepted a special teaching position in Creative Literature at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. The university created this job for him because of his achievements as a poet, editor, and critic during the Harlem Renaissance. He taught about literature and also lectured on many topics related to the lives and civil rights of Black Americans. He held this job until he died. In 1934, he also became the first African-American professor at New York University. There, he taught classes on literature and culture.

Music Career

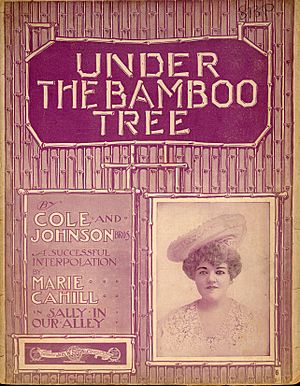

In 1901, Johnson moved to New York City with his brother J. Rosamond Johnson to work in musical theater. They wrote many hit songs together. James wrote the words and his brother wrote the music for songs like "Tell Me, Dusky Maiden" and the spiritual "Dem Bones".

Johnson wrote a poem that later became the song "Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing". He wrote it to honor the famous educator Booker T. Washington. Five hundred schoolchildren recited the poem as a tribute to Abraham Lincoln's birthday. This song became very popular and is known as the "Negro National Anthem." The NAACP adopted and promoted this title. The song includes these lines:

After their success, the brothers worked on Broadway and with producer Bob Cole. Johnson also worked on an opera called Tolosa with his brother. It made fun of the U.S. taking over islands in the Pacific. Because of his success as a Broadway songwriter, Johnson became part of the upper levels of African-American society in New York.

Diplomatic Work

In 1906, President Roosevelt appointed Johnson as a consul in Puerto Cabello, Venezuela. In 1909, he moved to Corinto, Nicaragua. While he was in Corinto, a rebellion started against President Adolfo Diaz. Johnson showed he was a skilled diplomat during these difficult times.

His diplomatic jobs also gave him time to work on his writing. He wrote large parts of his novel, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, and his poetry collection, Fifty Years, during this period. His poems were published in major magazines like The Century Magazine.

Literary Works

Johnson's first big success as a writer was the poem "Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing" (1899). His brother Rosamond later set it to music. This song became known as the "Negro National Anthem."

While working as a diplomat, Johnson finished his most famous book, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man. He published it without his name in 1912. He did this to avoid any problems that might hurt his diplomatic career. It wasn't until 1927 that Johnson said he wrote the novel. He made sure to say it was mostly fiction, not his own life story.

During this time, he also published his first poetry collection, Fifty Years and Other Poems (1917). This book showed that he was becoming more involved in politics and using Black everyday language in his writing.

Johnson returned to New York and became a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. He greatly admired Black artists, musicians, and writers. He worked to make more people aware of their amazing creativity. In 1922, he published an important collection called The Book of American Negro Poetry. It had a "Preface" that celebrated the power of Black culture. He also put together and edited the book The Book of American Negro Spirituals, published in 1925.

He also continued to publish his own poetry. Johnson's collection God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927) is considered very important. In it, he showed that Black folk life could be the subject of serious poetry. He also wrote about the violence of racism in poems like "Fragment," which says slavery goes against God's love and law.

After the Harlem Renaissance grew in the 1920s, Johnson reissued his poetry collection, The Book of American Negro Poetry, in 1931. He added many new poets to it. This helped share African-American poetry with a much wider audience and inspired younger poets.

In 1930, he published a study about society called Black Manhattan. His book Negro Americans, What Now? (1934) argued for full civil rights for African Americans. By this time, many African Americans had moved from the South to Northern and Midwestern cities in the Great Migration. However, most still lived in the South. There, they could not vote and faced Jim Crow laws and white supremacy. Outside the South, many faced unfair treatment but had more political rights and better chances for education and jobs.

Film Work

At least one of Johnson's works led to a movie. Go Down, Death! was a film made by Harlemwood Studios, directed by Spencer Williams. The movie featured an all African-American cast. It also showed a fun, middle-class club with dancing, a band, drinks, and gambling at the beginning.

Death

Johnson died in 1938 while on vacation in Wiscasset, Maine. The car his wife was driving was hit by a train. More than 2,000 people attended his funeral in Harlem. Johnson's ashes are buried at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Legacy and Honors

- 1904: Received an honorary master's degree from Atlanta University.

- 1925: Awarded the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP for outstanding achievement by an American Negro.

- 1928: Won the Harmon Gold Award for God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927).

- 1929: Received a grant from the Julius Rosenwald Fund.

- 1933: Won the W. E. B. Du Bois Prize for Negro Literature.

- Received honorary doctorates from Talladega College (1917) and Howard University (1923).

- 2007: Emory University in Atlanta created the James Weldon Johnson Institute for Advanced Interdisciplinary Studies in his honor. It was later renamed the James Weldon Johnson Institute for the Study of Race and Difference.

- The James Weldon Johnson building at Coppin State University in Baltimore, Maryland, is named after him.

- The James Weldon Johnson Middle School in Jacksonville, Florida, his birthplace, is named in his honor.

- The James Weldon Johnson Community Library in St. Petersburg, Florida, is named after him.

- On February 2, 1988, the United States Postal Service issued a 22-cent postage stamp in his honor.

- On August 11, 2020, the Jacksonville, Florida City Council renamed Hemming Park to James Weldon Johnson Park.

- In 2021, the Maine Legislature made June 17 James Weldon Johnson Annual Observance Day. They also created a group to educate the public about Johnson's life and work to end racism.

Books

Poetry

- Fifty Years and Other Poems (1917)

- God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927)

- Saint Peter Relates an Incident: Selected Poems (1935)

Anthologies

- The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922, editor), a collection of poems

- The Book of Negro Spirituals (1925, editor), a collection of songs

- The Second Book of Negro Spirituals (1926, editor)

Other works

- The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (1912/1927, novel)

- Black Manhattan (1930, a study of society)

- Negro Americans, What Now? (1934, an essay)

See also

In Spanish: James Weldon Johnson para niños

In Spanish: James Weldon Johnson para niños

- African American musical theater

- Harlem Renaissance

- Red Summer of 1919

- List of first minority male lawyers and judges in Florida

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |