Civil rights movement (1896–1954) facts for kids

The Civil Rights Movement (1896–1954) was a long period when people, mostly using peaceful methods, worked to get full civil rights and equal treatment under the law for all Americans. This time had a big impact on the United States. It showed how common and harmful racism was. It also led to more social and legal acceptance of civil rights.

Two important decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court mark the beginning and end of this period. In 1896, the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling said that "separate but equal" racial segregation was allowed by the Constitution. But in 1954, Brown v. Board of Education overturned Plessy.

During this era, some groups like Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association were very successful for a while. Others, like the NAACP's legal fight against state-supported segregation, slowly gained important victories. These included cases about voting, housing, and schooling. Also, the Scottsboro Boys cases led to rulings in 1935 that made anti-racism laws more important in criminal justice.

After the Civil War, the United States expanded the legal rights of African Americans. In 1865, the 13th Amendment ended slavery. But it did not give citizenship or equal rights. In 1868, the 14th Amendment was added. It gave African Americans citizenship and promised "equal protection" under the law for everyone born in the U.S. The 15th Amendment (1870) said that race could not stop men from voting.

During Reconstruction (1865–1877), Northern troops were in the South. They worked with the Freedmen's Bureau to enforce these new amendments. Many Black leaders were elected to local and state jobs. Many also formed community groups, especially to support education.

Reconstruction ended in 1877 with a deal between Northern and Southern White leaders. Northern troops left the South. This allowed Southern White Democrats to regain power. They then had more freedom to create and enforce discriminatory practices. Many African Americans left the South in response, moving to Kansas in 1879.

The Supreme Court's decision in the Civil Rights Cases largely stopped efforts to end private discrimination. The Court said the 14th Amendment did not give Congress power to outlaw racial discrimination by private people or businesses.

Contents

- Understanding Segregation

- Political Opposition to Civil Rights

- Black Workers and Businesses

- Executive Orders for Fair Hiring

- The Black Church's Role

- Growth in Education

- Libraries and Desegregation

- The NAACP's Fight for Equality

- Jewish Community Support

- "The New Negro" Movement

- Labor Movement and Civil Rights

- Regional Council of Negro Leadership

Understanding Segregation

The Supreme Court's Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896 supported state-mandated discrimination in public transportation. It introduced the "separate but equal" idea. Justice Harlan disagreed, predicting that if states could separate people on trains, they could separate them everywhere.

The Plessy decision did not address an earlier case, Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886). This case said that a law that seems fair but is used unfairly is against the 14th Amendment.

While the Supreme Court later began to overturn laws that stopped African Americans from voting, Plessy allowed Southern states to enforce segregation in almost all public and private life. The Court soon extended Plessy to schools. In Berea College v. Kentucky, it upheld a Kentucky law that stopped a private college from teaching Black and White students together. Many states, especially in the South, used Plessy and Berea to create strict laws known as Jim Crow laws. These laws created a second-class status for African Americans.

In many places, African Americans could not share a taxi with White people. They had to use separate entrances, drink from separate water fountains, and use separate restrooms. They attended separate schools and were buried in separate cemeteries. They were often not allowed in restaurants or public libraries. Some parks had signs saying "Negroes and dogs not allowed."

The rules of racial segregation were very harsh, especially in the South. African Americans were expected to step aside for White people. Black men were not supposed to look White women in the eye. Black adults were often called "Tom" or "Jane" instead of "Mr." or "Miss" or "Mrs.."

Less formal segregation in the North slowly began to change. However, in 1941, the United States Naval Academy refused to play a lacrosse game against Harvard University because Harvard's team had a Black player.

Jackie Robinson's Baseball Debut (1947)

Jackie Robinson was a sports hero in the civil rights movement. He became the first African American to play professional sports in the major leagues. Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers of Major League Baseball on April 15, 1947. His first game happened before the U.S. Army was integrated, before the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, and before Rosa Parks or Martin Luther King Jr. became famous.

Political Opposition to Civil Rights

The "Lily-White" Movement

After the Civil War, Black leaders made good progress in the Republican Party. This made many White voters uncomfortable. In Texas, a term called lily-white movement was used to describe efforts by White conservatives to remove Black people from party leadership. This movement slowly pushed Black leaders out of the party. It was part of a larger effort to stop Black people from voting in the South.

By the late 1800s, the Democratic Party controlled most state legislatures in the South. From 1890 to 1908, they stopped most Black people and some poor White people from voting. Despite legal challenges by the NAACP, Democrats continued to find new ways to limit Black voting, such as white primaries, until the 1960s.

Nationally, the Republican Party tried to respond to Black interests. President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909) had mixed views on race. He invited Booker T. Washington to dinner at the White House, challenging racist attitudes. But he also started separating federal employees.

Republicans in Congress tried to pass federal laws against lynching, a severe form of racial violence. These laws were always blocked by Southern politicians. Lynchings, mostly of Black men in the South, had increased around the turn of the 20th century.

Stopping People from Voting

Opponents of Black civil rights used economic threats and violence at voting places in the 1870s and 1880s. Groups like the Red Shirts and White League used intimidation for the Democratic Party. By the early 1900s, White Democratic-controlled Southern states had passed laws and constitutional rules that stopped almost all eligible African-American voters. These rules, like poll taxes and literacy tests, were aimed at Black people and poor White people.

Mississippi passed a new constitution in 1890 with poll taxes, literacy tests, and complex residency rules. These greatly reduced the number of Black people who could register to vote. In 1898, the Supreme Court upheld this. Other Southern states quickly adopted similar plans. From 1890 to 1908, ten states adopted new constitutions to stop most Black people and many poor White people from voting. These measures lasted for decades until federal laws in the mid-1960s provided oversight for voting rights.

Black people were most affected. In many Southern states, Black voter turnout dropped to zero. Poor White people were also stopped from voting. For example, in Alabama by 1941, 600,000 poor White people and 520,000 Black people could not vote.

It was not until the 20th century that legal challenges by African Americans began to succeed in the Supreme Court. In 1915, in Guinn v. United States, the Court said Oklahoma's 'grandfather clause' was unconstitutional. Even though this affected states using the clause, state legislatures quickly found new ways to stop people from voting. Each new rule had to be challenged separately. The NAACP, founded in 1909, fought many of these rules.

One method the Democratic Party used was the white primary. This stopped the few Black people who managed to register from voting in the Democratic Party primary elections. Since the Republican Party was weak in the South, winning the Democratic primary was like winning the election. White primaries were not struck down by the Supreme Court until Smith v. Allwright in 1944.

Black Workers and Businesses

White society also kept Black people in lower-paying or less important jobs. Most Black farmers in the South in the early 1900s worked as sharecroppers or tenant farmers. Few owned land.

Employers and labor unions often limited African Americans to the worst-paid jobs. Because good jobs were scarce, positions like Pullman Porter or hotel doorman became respected jobs in Black communities in the North. The growth of railroads meant tens of thousands of Black people moved North to work, for example, for the Pennsylvania Railroad, during the Great Migration.

The Golden Age of Black Entrepreneurship

Even though political and legal rights were at a low point in the early 1900s, Black business owners succeeded. They created thriving businesses that served Black customers, including professionals. In cities, the Black population and its income grew. This created opportunities for many businesses, from barbershops to insurance companies.

Historian Juliet Walker calls the 1900s-1930s the "Golden age of black business." The number of Black-owned businesses quickly doubled, from 20,000 in 1900 to 40,000 in 1914. One famous business owner was Madame C.J. Walker (1867–1919). She built a national franchise business based on her successful hair care products.

Booker T. Washington, who led the National Negro Business League and was president of the Tuskegee Institute, was a major supporter of Black businesses. He traveled to encourage local business owners to join the national league.

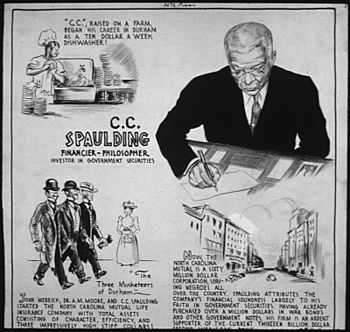

Charles Clinton Spaulding (1874–1952) was a leading Black American business leader. He founded North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company, which became America's largest Black-owned business.

However, Black businesses struggled in the rural South, where most Black people lived. Farmers depended on White merchants who offered credit. Black business owners had little access to credit for this kind of business.

Executive Orders for Fair Hiring

President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued two Executive Orders that told defense contractors to hire, promote, and fire people without racial discrimination. In places like West Coast shipyards, Black people started getting more skilled, higher-paying jobs and supervisory roles.

The Black Church's Role

Black churches were central to community life. They were important leaders and organizers in the civil rights movement. Their history as a meeting place for the Black community and a link between Black and White worlds made them perfect for this role.

During this time, independent Black churches grew stronger. Their leaders were often strong community leaders too. Black people had left White churches after the Civil War to create their own churches free from White control. They quickly formed state groups and, by 1895, joined several into the Black National Baptist Convention. Other independent Black churches, like the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, also grew in the South. These churches were centers for community activities, especially organizing for education.

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was one of many famous Black ministers involved in the later civil rights movement. Many other ministers were also important activists, especially in the 1950s and 1960s.

Growth in Education

Many talented Black people became teachers, a highly respected job. They believed education was the main way to advance. Segregated schools for Black children in the South were underfunded and had shorter school years in rural areas. Despite segregation, in Washington, D.C., Black and White teachers were paid the same because they were federal employees. Excellent Black teachers in the North earned advanced degrees and taught in respected schools. These schools trained future leaders in cities like Chicago, Washington, and New York, where Black populations grew due to the Great Migration.

Education was a major success for the Black community in the 1800s. Black leaders in Reconstruction governments helped create public education in every Southern state. Despite challenges, by 1900, the African-American community had trained 30,000 African-American teachers in the South. Most Black people could read and write.

Northern groups helped fund schools and colleges to train African-American teachers and other professionals. The American Missionary Association helped fund many private schools and colleges in the South. These schools worked with Black communities to train generations of teachers and leaders. Wealthy business owners, like George Eastman, also gave large donations to Black educational institutions like Tuskegee Institute.

In 1862, the U.S. Congress passed the Morrill Act. This law provided federal money for a land-grant college in each state. But 17 states refused to admit Black students. So, Congress passed the second Morrill Act in 1890. It required states that excluded Black students to open separate colleges and share the funds fairly. These colleges became today's public historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). Along with private HBCUs and unsegregated colleges in the North and West, they offered higher education to African Americans.

In the 1800s, Black people formed social groups across the South and North, including many women's clubs. They created and supported organizations that improved education, health, and well-being for Black communities. After 1900, Black men and women also started their own college fraternities and sororities. These groups created more networks for service and cooperation. For example, Alpha Phi Alpha, the first Black intercollegiate fraternity, was founded at Cornell University in 1906. These new organizations strengthened independent community life under segregation.

Libraries and Desegregation

Library services for Black people, especially in the South, were slow to develop. In the early 1900s, there were only a few libraries available, mostly on private property. The Western Colored Branch, opened in 1908, was the first public library in the South for African Americans. It was funded by a Carnegie grant. After this, other similar libraries were built, often with black schools.

The Tougaloo Nine

After the Brown v. Board of Education decision, efforts were made to desegregate public libraries and other facilities. The Tougaloo Nine were a group of African-American college students. In 1961, they bravely tried to end segregation at the Jackson, Mississippi Public Library. They simply asked for a philosophy book from the "whites only" branch. They were refused and told to leave. They chose to stay despite being harassed and were arrested. There were similar events during the Civil Rights Movement. Peaceful protests by students in libraries helped expand access.

The NAACP's Fight for Equality

The Niagara Movement and the NAACP's Start

Around 1900, Booker T. Washington was seen by many, especially White people, as the main spokesperson for African Americans. Washington, who led the Tuskegee Institute, taught a message of self-reliance. He urged Black people to focus on improving their economic situation rather than demanding social equality right away. Publicly, he accepted Jim Crow and segregation for a short time. But privately, he helped fund court cases that challenged these laws.

W. E. B. Du Bois and others in the Black community disagreed with Washington's approach to segregation. In 1905, Du Bois and other Black activists met in Canada near Niagara Falls. They called for voting rights for all men, an end to all forms of racial segregation, and more education for everyone. This group was called the Niagara Movement. It faced opposition from Washington and eventually broke apart by 1908.

Du Bois then joined with other Black leaders and White activists to create the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. Du Bois also became the editor of its magazine, The Crisis. In its early years, the NAACP focused on using the courts to fight Jim Crow laws and rules that stopped people from voting. It successfully challenged a law in Louisville, Kentucky that required residential segregation in Buchanan v. Warley (1917). It also won a Supreme Court ruling against Oklahoma's grandfather clause in Guinn v. United States (1915). This clause had stopped most illiterate Black voters from voting.

After World War II, African-American veterans returned home. Their experiences made them demand their constitutional rights as citizens even more. From 1940 to 1946, the NAACP's membership grew from 50,000 to 450,000.

Ending Segregation in Schools

The NAACP's legal team, led by Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall, worked for decades to overturn the "separate but equal" idea from Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). Instead of asking lawmakers or the president, they focused on court challenges. They knew that Congress was controlled by Southern segregationists.

The NAACP's first cases did not directly challenge "separate but equal." Instead, they tried to show that segregated facilities in transportation, schools, and parks were not truly equal. These facilities were usually underfunded and had old textbooks. These cases helped set the stage for overturning Plessy v. Ferguson.

Marshall believed it was time to end "separate but equal." The NAACP decided their goal was "obtaining education on a nonsegregated basis." The first case Marshall argued on this basis was Briggs v. Elliott. The NAACP also filed challenges to segregated education in other states. In Topeka, Kansas, the local NAACP chose Oliver Brown to file a lawsuit. He was a pastor and father of three girls. The NAACP told him to try to enroll his daughters in a local White school. After he was rejected, Brown v. Board of Education was filed. This case and several others went to the Supreme Court and were combined under the name Brown.

In December 1952, the Supreme Court heard the case but could not decide. They postponed it for a year. In September 1953, Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson died. He was replaced by Earl Warren, who was known for his moderate views on civil rights.

After the case was heard again in December, Warren worked to convince his fellow judges to make a unanimous decision to overturn Plessy. In May 1954, Warren announced the Court's decision. He wrote that "segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race" was unconstitutional. This was because it took away "equal educational opportunities" from minority children and thus denied them equal protection under the law.

Many Southern leaders strongly resisted the ruling. The Governor of Virginia, Thomas B. Stanley, said he would "use every legal means...to continue segregated schools." Some school districts closed rather than integrate.

Many Senators and members of the House of Representatives, mostly Southern Democrats, signed "The Southern Manifesto." They promised to resist the decision by "lawful means." By the fall of 1955, Cheryl Brown started first grade at an integrated school in Topeka. This was a major step toward equality for African Americans.

Jewish Community Support

Many people from the American-Jewish community supported the civil rights movement. Several co-founders of the NAACP were Jewish. Later, many of its White members and leaders came from the Jewish community.

Jewish philanthropists actively supported the NAACP and other civil rights groups, as well as schools for African Americans. The Jewish philanthropist Julius Rosenwald helped build thousands of schools for Black youth in the rural South. Public schools were segregated, and Black facilities were historically underfunded. Rosenwald worked with Booker T. Washington and Tuskegee University. He created a fund that provided initial money for building. Black communities often raised additional funds themselves through community events, donating land, and labor. At one time, about 40% of rural Southern Black children attended Rosenwald elementary schools. Nearly 5,000 were built in total. Rosenwald also gave money to HBCUs like Howard, Dillard, and Fisk universities.

The 2000 PBS show From Swastika to Jim Crow talked about Jewish involvement. It explained that Jewish scholars who fled or survived the Holocaust after World War II came to teach at many Southern schools. They connected with Black students.

After World War II, groups like the American Jewish Committee and Anti-Defamation League (ADL) actively promoted civil rights.

"The New Negro" Movement

Fighting in World War I and seeing different racial attitudes in Europe influenced Black veterans. They came home demanding the freedoms and equality they had fought for. But conditions at home were still bad. Some veterans were even attacked while wearing their uniforms. This generation had a more militant spirit. They urged Black people to fight back when attacked. A. Philip Randolph used the term New Negro in 1917. It became a popular phrase to describe the new spirit of militancy and impatience after the war.

During the Great Migration, hundreds of thousands of African Americans moved to Northern industrial cities before and after World War I. Another wave of migration during and after World War II led many to West Coast cities. They were escaping violence and segregation and looking for jobs. These growing Northern communities faced familiar problems like racism and poverty. But in the North, men could vote (and women after 1920), and there were more chances for political action than in the South.

Marcus Garvey and the UNIA

Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) grew quickly in these new Northern communities in the early 1920s. Garvey's plan was different from mainstream civil rights groups like the NAACP. Instead of seeking integration, Garvey's idea of Pan-Africanism, known as Garveyism, encouraged economic independence within the system of racial segregation in the United States. He also promoted an African Orthodox Church with a Black Jesus. He urged African Americans to "return to Africa," at least in spirit. Garvey gained thousands of supporters in the U.S. and the Caribbean.

Garvey's movement was a mix of self-reliance and separatism. It combined ideas that Booker T. Washington might have supported with a rejection of colonialism and racial inferiority.

The movement quickly declined after the federal government convicted Garvey for mail fraud in 1922. He was deported to his home country of Jamaica in 1927. While the movement struggled without him, it inspired other self-help and separatist movements that followed.

Labor Movement and Civil Rights

The labor movement had often excluded African Americans. However, some left-wing activists in the labor movement made progress in the 1920s and 1930s. A. Philip Randolph, a long-time member of the Socialist Party of America, became the leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) in 1925. The union faced opposition from the Pullman Company and even some Black community leaders. The union eventually gained support by linking its organizing efforts with the larger goal of Black empowerment. The union won recognition from the Pullman Company in 1935 and a contract in 1937.

The BSCP became the only Black-led union within the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1935. Randolph remained a voice for Black workers within the labor movement. He demanded an end to Jim Crow unions within the AFL. BSCP members like Edgar Nixon played a big role in the civil rights struggles of later decades.

Many unions, especially the Packinghouse Workers and the United Auto Workers, made civil rights part of their goals. They achieved improvements for workers in meatpacking and other industries. The Transport Workers Union of America worked with Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., the NAACP, and the National Negro Congress to fight employment discrimination in public transit in New York City in the early 1940s.

Unions were very vocal in calling for an end to racial discrimination by defense industries during World War II. They also had to fight racism within their own members. Some White workers went on "hate strikes" and refused to work with Black co-workers. While many of these strikes were short, one in Philadelphia in 1944 lasted two weeks. It ended only when the Roosevelt administration sent troops and arrested the strike leaders.

Randolph and the BSCP took the fight against employment discrimination even further. They threatened a March on Washington in 1942 if the government did not outlaw racial discrimination by defense contractors. Randolph only canceled the march after getting important promises from the Roosevelt administration.

The Scottsboro Boys Cases

In 1931, the NAACP and the Communist Party USA supported the "Scottsboro Boys." These were nine Black men who were arrested and sentenced to death for allegedly assaulting two White women. The legal campaign for the Scottsboro Boys led to two important Supreme Court decisions (Powell v. Alabama and Norris v. Alabama). These rulings expanded the rights of defendants. The political campaign saved all the defendants from the death sentence and eventually led to freedom for most of them.

The Scottsboro defense was one of many cases by the International Labor Defense (ILD) in the South. For a time in the 1930s, the ILD was very active in defending Black people's civil rights. Its campaigns helped focus national attention on the difficult conditions Black defendants faced in the criminal justice system in the South.

International Pressure

The way the United States treated African Americans affected its image as a world leader and supporter of democracy. The global challenge from Communism made Western democracies change their old racial attitudes. Incidents of discrimination in the U.S. were widely reported in other countries. The victory over Nazis and Fascists in World War II also helped set the stage for the civil rights movement.

Regional Council of Negro Leadership

On December 28, 1951, T. R. M. Howard, a Black entrepreneur and leader in Mississippi, founded the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL) with other key Black leaders. The RCNL, based in the all-Black town of Mound Bayou, at first did not directly challenge "separate but equal." Instead, it worked to ensure that facilities were truly "equal." It often pointed out that inadequate schools were a main reason Black people moved North. It called for equal school terms for both races. From the start, the RCNL also promised a full fight for unrestricted voting rights.

The RCNL's most famous member was Medgar Evers. After graduating from Alcorn State University in 1952, he moved to Mound Bayou. Evers soon became the RCNL's program director. He helped organize a boycott of gas stations that did not provide restrooms for Black people. As part of this, the RCNL gave out about 20,000 bumper stickers that said "Don't Buy Gas Where You Can't Use the Rest Room." Starting in 1953, it directly challenged "separate but equal" and demanded integration of schools.

The RCNL's yearly meetings in Mound Bayou between 1952 and 1955 drew crowds of 10,000 or more. They featured speeches by important figures like Rep. William L. Dawson and NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall. These events were like "a huge all-day camp meeting: a combination of pep rally, old-time revival, and Sunday church picnic." The conferences also had discussions and workshops on voting rights, business ownership, and other topics. Attending these meetings was a life-changing experience for many future Black leaders of the 1960s, such as Fannie Lou Hamer and Medgar Evers' wife, Myrlie Evers-Williams.

On November 27, 1955, Rosa Parks attended one of these speeches at Dexter Avenue Church in Montgomery. The host was a then little-known Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.. Parks later said she was thinking of Till when she refused to give up her seat four days later.

|

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |