History of African-American education facts for kids

The History of African-American education looks at the schools and learning opportunities for African Americans in the United States. It also covers the rules and discussions around these schools. Before the 1950s, many schools for black students were separate from schools for white students. These were often called "Negro schools" or "colored schools." They started after the American Civil War, during the Reconstruction era, as free public schools for people who had been enslaved. After 1877, these schools continued, but they usually received much less money than white schools.

Contents

A New Start: Education After Slavery

The Reconstruction Era (1863-1876)

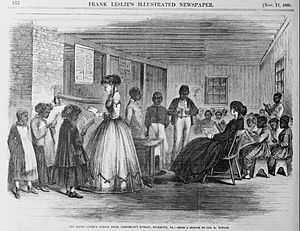

After the Civil War, during a time called the Reconstruction Era, many new schools for black people were started in the South. These schools were created by the government, by white religious groups, and by black communities themselves. For the first time, public schools, which are paid for by the government, were set up during this period.

Many groups from the North, especially religious ones, also opened private schools and colleges for formerly enslaved people across the South. Some schools were also set up in the North, like the African Free School in New York.

Creating Private Schools

Many large Protestant churches helped start and pay for these schools. The American Missionary Association was very active, providing money for many years. The Catholic Church also opened some schools for black students, often run by nuns. Examples include St. Frances Academy in Baltimore (1828) and St. Mary's Academy in New Orleans (1867).

The African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), which was an all-black church, strongly believed in education. They helped create Wilberforce University in Ohio, one of the first historically black colleges (HBCUs). By 1880, the AME Church ran over 2,000 schools, mostly in the South. They used church buildings as classrooms, and ministers and their wives often taught.

Freedmen's Bureau Schools

The U.S. government created the Freedmen's Bureau to help formerly enslaved people. This bureau set up a large network of schools. Many leaders for these schools came from black people in the North who had never been enslaved.

Black communities fought hard for good public schools. They saw education as key to gaining freedom and equal rights. Before the war, many Southern states had laws against teaching black people to read. Because of this, many black people couldn't read or write. So, creating new schools was a top priority.

The Freedmen's Bureau opened about 1,000 schools across the South for black children. Many students were eager to learn. By the end of 1865, over 90,000 formerly enslaved people were enrolled in public schools. The schools taught subjects similar to those in Northern schools. However, after Reconstruction ended, state funding for black schools became very low, and facilities were often poor.

Many teachers in Freedmen's Bureau schools were well-educated women from the North, driven by their religious beliefs and opposition to slavery. About a third of the teachers were black, and they were often the most dedicated to racial equality.

Southern States Create Public Schools

Formerly enslaved people were the first Southerners to push for public education for everyone, paid for by the state. Black leaders played a big role in getting this idea into state laws during Reconstruction. Some enslaved people had learned to read secretly before the war. Many black communities also started their own "native schools" and Sunday schools to teach reading.

During Reconstruction, public schools were created, but they were mostly separate for black and white students everywhere except New Orleans. Elementary schools and some high schools were built in cities and occasionally in the countryside.

However, rural areas faced many challenges. Rural schools were often one-room buildings and only about half of the younger children attended. Teachers were paid very little, and sometimes their pay was delayed. After Reconstruction, when white officials took control, they consistently gave much less money to black schools.

Higher Education: Creating Colleges

During Reconstruction, state governments in the South also started colleges for formerly enslaved people, like Alcorn State University in Mississippi. These colleges continued to operate even after Republicans lost control of state governments. To train elementary school teachers, states and cities also created "normal schools" (teacher training schools). These schools helped many African Americans become teachers. By 1900, most African Americans could read and write.

In the late 1800s, the U.S. government passed laws to fund higher education. When they saw that black students were not allowed in land-grant colleges in the South, Congress passed a second law in 1890. This law said that if states excluded black students from their existing land-grant colleges, they had to open separate colleges for black students and share the money fairly. These colleges became today's public historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

At the start of Reconstruction, most teachers in integrated schools were white. Some black educators felt that these white teachers sometimes made black students feel less capable. This led to a lack of trust in the public education system at that time.

Almost all public and private schools in the South were either all-white or all-black until the 1950s. Berea College was a rare exception, but a Kentucky law forced it to stop enrolling black students in 1904. New Orleans was also a partial exception, with some integrated schools during Reconstruction.

The Jim Crow Era (After 1876)

After white leaders regained power in the South in the 1870s, they passed Jim Crow laws. These laws made segregation mandatory, meaning black and white people were kept separate in many areas of life, including schools. Black schools almost always received much less money than white schools. The South was also very poor after the war.

Into the 1900s, black schools often had old, second-hand books and buildings. Teachers were paid less and had larger classes. However, in Washington, D.C., black and white public school teachers were paid the same because they were federal employees.

The Virginia Constitution of 1870 created a public education system, but schools were segregated. In rural areas, one teacher often taught all subjects and grades. These schools were always overcrowded because they were underfunded. For example, in 1900, black schools in Virginia had 37 percent more students than white schools on average. This unfairness continued for many years.

20th Century: Progress and Challenges

Many talented black individuals became teachers, a highly respected profession. Even though black schools in the South were underfunded, black teachers were dedicated. By 1900, the African-American community had trained about 30,000 black teachers in the South. Most black people had also learned to read and write.

Northern groups and churches helped fund teacher training schools and colleges for African Americans. The American Missionary Association helped create many private schools and colleges in the South. Wealthy business leaders, like George Eastman (who founded Kodak), also gave large donations to black educational institutions like Tuskegee Institute.

Rosenwald Schools

Julius Rosenwald, who owned Sears, Roebuck, and Company, was a generous giver. After meeting Booker T. Washington in 1911, Rosenwald started a fund to improve education for black students in the South, especially in rural areas. His fund helped build over 5,300 schools by the time he died in 1932. He created a system where local communities had to raise some money themselves and work together to maintain the schools. Black communities often donated land and labor to help build these schools.

Today, many Rosenwald schools have been restored and are seen as important historical sites for African American education.

Sarah Roberts vs. City of Boston (1849)

The case of Sarah Roberts vs. the City of Boston was about a five-year-old black girl named Sarah Roberts. Her parents tried to send her to a nearby school that was mostly white, but she was not allowed in because of her race. This was an early attempt to challenge racial segregation in education.

The court ruled against the Roberts family, saying that school officials could deny admission based on race. However, this case helped highlight the unfairness of segregation. It also helped set the stage for future challenges, including the famous 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, which declared that racial segregation in public schools was against the law.

Fight for Equal Funding

In the 1930s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) started a campaign to make schools equal, even within the "separate but equal" system that was allowed by the Supreme Court's 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision. However, white opposition made it hard for black schools to get the money they needed.

Studies showed huge differences in spending. For example, in the late 1920s, Georgia spent $4.59 per year on each African-American child compared to $36.29 on each white child. The NAACP won some victories, especially in getting equal pay for teachers.

Citizenship Schools (1950s)

Septima Poinsette Clark was an educator and civil rights activist who created "citizenship schools" in 1957. These schools started as secret reading classes for African American adults in the South. Citizenship schools helped black Southerners learn to read and understand their rights, especially the right to vote. They also trained activists and leaders for the Civil Rights Movement. These schools trained over 10,000 teachers and helped about 700,000 African Americans register to vote.

Freedom Schools (1960s)

In 1964, Charles E. Cobb Jr., an activist with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), suggested creating a network of Freedom Schools. These schools aimed to help black students become agents of social change for the Civil Rights Movement. Black educators also used these schools to provide education in areas where public schools for black students were closed down in response to the Brown v. Board of Education ruling. By the end of the summer in 1964, more than 40 Freedom Schools were open, serving nearly 3,000 students.

Desegregation

Public schools were officially desegregated in the United States in 1954 by the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education. However, many schools remained segregated in practice because of housing patterns. President Dwight Eisenhower enforced the Supreme Court's decision by sending U.S. Army troops to Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957 to protect the "Little Rock Nine" students as they entered school. This was the first time since Reconstruction that a president sent federal troops to the South to protect the rights of African Americans.

Busing

In 1971, the Supreme Court allowed the government to use mandatory busing to integrate schools in cities like Charlotte, North Carolina. This meant students were bused to schools outside their neighborhoods to create more diverse classrooms. The idea was to fight segregation that had developed over time. However, busing was controversial because it took students away from their local communities. Some school districts also tried "magnet schools," which were special schools designed to attract students from different backgrounds voluntarily.

21st Century: Re-segregation

The desegregation of U.S. public schools reached its highest point around 1988. Since then, schools have become more segregated again. This is partly due to changes in where people live, with more growth in suburbs.

According to a 2005 report, the number of black students in mostly white schools was lower than it had been since 1968. Changing populations, with more growth in the South and Southwest and new immigrant groups, have also changed school populations in many areas.

Black school districts continue to try different programs to improve student performance. In Omaha, Nebraska, after busing ended in 1999, some observers felt that public schools had become segregated again. In 2006, a state senator proposed creating separate school districts for black, white, and Hispanic communities in Omaha. This idea was controversial, with opponents calling it "state-sponsored segregation."

A 2003 study suggested that white teachers leaving mostly black schools in the South is a result of federal court decisions that limited methods like busing. Teachers and principals also mention challenges like poverty in schools and teachers choosing to work closer to home or in higher-performing schools.

See also

- Education during the slave period in the United States

- African Americans

- Freedmen's Schools

- Historically black colleges and universities

- Racial integration

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |