Meharry Medical College facts for kids

|

|

|

Former names

|

Medical Department of Central Tennessee College |

|---|---|

| Motto | Worship of God through Service to Mankind |

| Type | Private historically black medical school |

| Established | 1876 |

|

Religious affiliation

|

United Methodist Church |

|

Academic affiliation

|

ORAU |

| Endowment | $156.7 million (2020) |

| President | James E. K. Hildreth |

| Students | 956 (Fall 2021) |

| Location |

,

,

United States

36°10′01″N 86°48′25″W / 36.167°N 86.807°W |

Meharry Medical College is a private, historically black medical school. It is connected with the United Methodist Church and is located in Nashville, Tennessee.

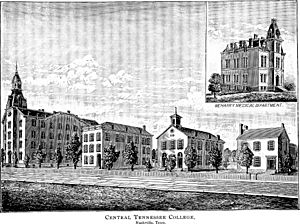

The college started in 1876 as the Medical Department of Central Tennessee College. It was the first medical school in the South for African Americans. At that time, many African Americans were not allowed into colleges. Meharry Medical College was created to help solve this problem.

In 1915, Meharry Medical College became its own separate school. Today, it is the largest private school for African Americans in the United States. It focuses on training health care workers and scientists. The school has always welcomed students of all races.

Meharry Medical College has several different schools. These include the School of Medicine and the School of Dentistry. It also has schools for graduate studies and applied computational sciences. Students can earn degrees like Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) and Doctor of Dental Surgery (D.D.S.). They can also get master's and Ph.D. degrees in health sciences.

Meharry trains many African-American doctors and dentists. It also has the highest number of African Americans earning Ph.D.s in biomedical sciences. The school owns and edits the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. About 76% of Meharry graduates work in communities that need more health care.

Contents

Meharry's Story: A Helping Hand

Meharry Medical College was one of six medical schools started in Tennessee between 1876 and 1900. These schools opened after the Civil War, when slavery ended. There were very few African-American doctors then. Many freed people needed medical care.

Because of segregation, most hospitals did not accept African Americans. Many white doctors also did not treat them. To fix this, people like Samuel Meharry helped create medical schools for African Americans. Organizations like the National Medical Association also supported these efforts.

The college is named after Samuel Meharry. He was a young Irish American who traded salt and grit. Once, a family of freed people helped him when he was in trouble. Meharry promised to help their community when he could. Later, he and his four brothers donated $15,000 to start the college.

In 1875, students at Central Tennessee College (CTC) wanted a medical school. The college president, John Braden, spoke with Samuel Meharry. With the Meharry brothers' donation and help from the Methodist Episcopal Church, the Medical College at CTC opened in 1876. Classes began in the basement of a church with nine students.

The medical program first lasted two years. It grew to three years in 1879 and four years in 1893. Dr. George W. Hubbard was the first president. The first student graduated in 1877.

Growing the College: New Departments

In 1886, a Dental Department was added. A Pharmacy Department followed in 1889. By 1896, half of all "regularly educated physicians" in the South had graduated from Meharry.

A nursing school started in 1900. A training hospital, Mercy Hospital, was built in 1901. This hospital was replaced in 1916 and named the George W. Hubbard Hospital. A large auditorium was built in 1904.

In 1915, the medical department of Walden University became its own school. It was named Meharry Medical College. The college stayed in its original buildings. Walden University moved to a different campus in 1922.

Meharry's reputation improved in 1923. The American Medical Association (AMA) gave it a "grade-A institution" rating. This happened after Abraham Flexner helped with advice and funding.

Expanding Programs and Services

Since its start, Meharry Medical College has added many graduate programs. These programs are in science, medicine, and public health. In 1938, the School of Graduate Studies and Research was founded. The first master's degree in Public Health began in 1947.

In the 1950s, the nursing and dental technology schools closed. The Department of Psychiatry started in 1961. Meharry began to focus on understanding health differences. In 1968, Meharry created the Matthew Walker Health Center. This center provides health services to the community. A Ph.D. degree in basic sciences was also added in 1968.

By the early 1970s, most African-American doctors had trained at Meharry or Howard University. In 1972, Meharry started getting federal grants. These grants helped medical schools with money problems. By 1976, the school campus covered 65 acres.

In 1981, Meharry faced a challenge with its accreditation. This was because there were not enough patients at Hubbard Hospital for students. Also, there were too many students for each teacher. In 1983, the school was allowed to work with patients at nearby veterans' hospitals. This helped the college get full accreditation again. By 1986, about 46% of all black faculty members in medical schools had graduated from Meharry.

A Ph.D. program was added in 1972. An M.D./Ph.D. program started in 1982. In 2004, Meharry created a Master's of Science in Clinical Investigation program.

The Hubbard Hospital closed in 1994. It was renovated and reopened in 1997 as the Metropolitan Nashville General Hospital. In 1999, the college partnered with Vanderbilt University.

In 2017, Meharry partnered with Hospital Corporation of America (HCA). This agreement allows Meharry's medical students to get clinical training at HCA's TriStar Southern Hills Medical Center. In 2019, Meharry also partnered with Detroit Medical Center. This partnership helps more Meharry students complete their studies there.

In September 2020, Michael Bloomberg donated $34 million to Meharry. This gift helps students with their school debt. It was the largest gift in Meharry's history at that time. In March 2022, MacKenzie Scott also donated $20 million to Meharry. In 2024, Bloomberg Philanthropies gave Meharry a $175 million gift to support the school's future.

Leaders of Meharry Medical College

George W. Hubbard was Meharry Medical College's first president. He served from 1876 until 1921.

The second president was John J. Mullowney, from 1921 to 1938. He made changes to improve Meharry's academic standing. He made admission rules stricter and added more faculty and research facilities. Two years after he took over, Meharry got its 'A' rating back.

Later presidents include:

- Edward Lewis Turner (1938–1944)

- M. Don Clawson (1944–1950)

- Harold D. West (1952–1966)

- Lloyd C. Elam (1968–1981)

- Richard G. Lester (1981–1982)

- David Satcher (1982–1993)

- John E. Maupin (1994–2006)

- Wayne J. Riley (2006–2013)

- Anna Epps (2013–2015)

- James E.K. Hildreth (2015–present)

From 1950 to 1952, a committee led the school. In 1952, Dr. Harold D. West became the first African-American president. He raised $20 million, which helped him make many improvements. He added a new part to Hubbard Hospital and bought land for the campus to grow.

Research and Discoveries

Meharry Medical College has a long history of research. This research helps improve health, especially for people who do not have good access to health care.

In 1893, Georgianna Esther Patton, Meharry's first female medical graduate, studied health in Liberia. She found that anemia and dropsy were common health problems there. In 1910, Arthur Melvin Townsend found that pellagra was caused by not getting enough nutrients.

In the 1950s, under President Harold D. West, Meharry started one of the first research programs on cancer differences. This program was supported by the American Cancer Society.

Since the 1970s, Meharry has been active in genetics research. Scientists Joseph Galley and Thomas Shockley studied keloid scarring. This condition affects people of African descent more often. In 1972, Meharry opened the Sickle Cell Center. It was one of the first centers in the U.S. to help newborns with inherited blood disorders.

In 2015, Dr. James EK Hildreth became president. He shifted Meharry's research to focus on personalized medicine. This means using information about a person's genes and other data to create special treatments.

Between 2013 and 2017, Meharry spent $96 million on research. In 2019, the college created the Office for Research and Innovation. This office helps different research areas work together. It manages grants, research rules, and new inventions.

Since 2020, Anil Shanker has led this office. He is a cancer immunologist. Under his leadership, Meharry has found new ways to get research funding. Annual research funding grew from $29 million in 2020 to $128 million by 2025. More faculty and students are now involved in research and clinical trials.

Meharry Medical College continues to expand its research. It works to solve health care needs. It has partnerships with many groups in the U.S. and around the world. Some of these include:

- NIH AIM-AHEAD Southeast Hub: Uses artificial intelligence to improve health.

- Center for Genome Research: Studies human genes.

- NSF Innovation-Corps Mid-South Hub: Helps new health businesses start.

- Chan Zuckerberg Initiative Partnership: Supports precision health research at HBCUs.

- Dry January USA: A public health program about alcohol use.

- Beacon of Hope program: Helps with clinical research.

- Equitable Breakthroughs in Medicine Development (EQBMED): Works to include more diverse people in clinical trials.

- The Diaspora Human Genomics Institute (DHGI): A non-profit that studies the genes of people of African ancestry.

- Together for CHANGE (T4C): Builds a gene database for African ancestry populations.

- Meharry DNA Learning Center: Teaches K-12 students and teachers about DNA.

Meharry also partners with other research institutions. These include the University of Memphis and the University of Zambia.

Meharry Medical College is a member of the United Nations Academic Impact. This is because of its work to improve health and reduce inequality worldwide.

The Office for Research and Innovation also publishes the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. This journal focuses on health issues for people who do not have good medical care. It is a leading journal for public health in the United States.

BS/MD Program

Meharry has partnerships with twelve universities. These partnerships help prepare students for medical school. The universities are: Alabama A&M University, Albany State University, Alcorn State University, Fisk University, Grambling State University, Hampton University, Jackson State University, Southern University, Tennessee State University, Virginia Union University, and Tuskegee University.

Famous Graduates

| Name | Class year | Notability |

|---|---|---|

| Lucinda Bragg Adams | 1907 | Composer, writer, and editor before becoming a doctor. |

| Daniel Sharpe Malekebu | 1917 | First Malawian to get a medical degree; Christian missionary. |

| Hastings Kamuzu Banda | 1937 | President of the Republic of Malawi. |

| Carl C. Bell | 1971 | Professor of psychiatry. |

| Emmett Ethridge Butler | 1934 | Physician and community leader. |

| Clive O. Callender | Transplant surgeon; founder of a program to educate minorities about organ donation. | |

| Donna P. Davis | 1975 | First African-American woman doctor in the United States Navy. |

| Tameka A. Clemons | 2003 | Biochemist and professor at Meharry. |

| Lillian Singleton Dove | 1917 | Early physician and surgeon in Chicago. |

| Jacob J. Durham | 1882 | Founder of Morris College. |

| Winston C. Hackett | First African American physician in Arizona. | |

| John Henry Hale | 1905 | Famous surgeon who performed 30,000 operations. |

| Robert Hayling | 1960 | Leader in the civil rights movement in St. Augustine, Florida. |

| Corey Hébert | 1994 | Celebrity physician and radio host. |

| Robert Walter Johnson | Tennis instructor for Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe. | |

| John S. Jackson | First African American surgeon and mayor of Lakeland, Florida. | |

| Robert Lee | 1944 | Dentist who moved to Ghana and practiced there for almost 50 years. |

| John Angelo Lester | 1895 | Professor and surgeon. |

| Monroe Alpheus Majors | 1886 | Physician, writer, and civil rights activist. |

| Eleanor L. Makel | 1943 | Supervising medical officer at St. Elizabeths Hospital. |

| Audrey F. Manley | 1959 | Surgeon General of the United States, President of Spelman College. |

| Lloyd Tevis Miller | 1893 | Medical director of the Afro-American Sons and Daughters Hospital. |

| Conrad Murray | Personal physician. | |

| Louis Pendleton | Dentist and civil rights leader. | |

| James Maxie Ponder | First African American physician in St. Petersburg, Florida. | |

| Theresa Greene Reed | 1949 | First African-American woman epidemiologist. |

| Charles Victor Roman | 1899 | Founder of a department at Meharry Medical College. |

| Frank S. Royal | 1968 | Chair of Meharry Medical College's board. |

| William B. Sawyer | Founder of Miami's first hospital for African Americans. | |

| C. O. Simpkins Sr. | Dentist and civil rights leader. | |

| Walter R. Tucker Jr. | Former mayor of Compton, California. | |

| Matthew Walker Sr. | 1934 | Former professor and chairman of surgery at Meharry. |

| Georgia E. L. Patton Washington | 1893 | First African American woman licensed to practice medicine in Tennessee. |

| Josie English Wells | 1904 | First woman to join Meharry's faculty. |

| Emma Rochelle Wheeler | 1905 | Founder of Walden Hospital and nursing school. |

| Charles H. Wright | 1943 | Founder of the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History. |

| Joyce Yerwood | 1933 | Physician and social justice advocate. |