Althea Gibson facts for kids

Gibson in 1956

|

|

| Country (sports) | |

|---|---|

| Born | August 25, 1927 Clarendon County, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | September 28, 2003 (aged 76) East Orange, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Height | 5 ft 11 in (1.80 m) |

| Retired | 1958 |

| Plays | Right-handed |

| Int. Tennis HoF | 1971 (member page) |

| Singles | |

| Career titles | 56 |

| Highest ranking | No. 1 (1957) |

| Grand Slam singles results | |

| Australian Open | F (1957) |

| French Open | W (1956) |

| Wimbledon | W (1957, 1958) |

| US Open | W (1957, 1958) |

| Doubles | |

| Grand Slam doubles results | |

| Australian Open | W (1957) |

| French Open | W (1956) |

| Wimbledon | W (1956, 1957, 1958) |

| US Open | F (1957, 1958) |

| Grand Slam mixed doubles results | |

| Australian Open | SF (1957) |

| French Open | QF (1956) |

| Wimbledon | F (1956, 1957, 1958) |

| US Open | W (1957) |

Althea Gibson (born August 25, 1927 – died September 28, 2003) was an amazing American tennis player and professional golfer. She was one of the first Black athletes to break through racial barriers in international tennis. In 1956, she made history by becoming the first Black player to win a major tennis event, called a Grand Slam, at the French Open.

The next year, she won both Wimbledon and the US Nationals (which is now the US Open). She won both again in 1958. Because of her incredible achievements, the Associated Press voted her the Female Athlete of the Year in both 1957 and 1958.

Overall, Althea Gibson won 11 Grand Slam titles. This included five singles titles, five doubles titles, and one mixed doubles title. Many people in tennis, like Bob Ryland, who coached Venus and Serena Williams, said she was one of the greatest players ever. She was honored in the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1971 and the International Women's Sports Hall of Fame in 1980. In the early 1960s, she also became the first Black player to compete in the Ladies Professional Golf Association for golf.

Althea Gibson achieved her success at a time when racism and unfair treatment were common in sports and society. She was often compared to Jackie Robinson, who broke barriers in baseball. Billie Jean King said Althea's path was tough, but she never gave up. Former New York City Mayor David Dinkins said Althea inspired everyone because of what she did when it was so hard for Black people to play tennis. Venus Williams shared that Althea's achievements helped pave the way for her own success and the success of other players like Serena.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Althea Gibson was born on August 25, 1927, in Silver, Clarendon County, South Carolina. Her parents, Daniel and Annie Bell Gibson, were sharecroppers on a cotton farm. During the Great Depression, many farmers in the South faced hard times. So, in 1930, her family moved to Harlem, New York, as part of the Great Migration. Her three sisters and brother were born there.

Their apartment was on 143rd Street, which was a special play area for children. The street was blocked off during the day so kids could play organized sports. Althea quickly became very good at paddle tennis. By 1939, when she was 12, she was the New York City women's paddle tennis champion.

Althea left school at 13. She spent her time playing basketball and watching movies, and sometimes got into trouble. After leaving school, she faced some difficult times and lived for a while in a safe place run by a Catholic church.

In 1940, some of Althea's neighbors helped her join the Cosmopolitan Tennis Club in Harlem. They paid for her membership and lessons. At first, Althea didn't like tennis, thinking it was for "weak people." She said, "I kept wanting to fight the other player every time I started to lose a match." But in 1941, she entered her first tournament, the American Tennis Association (ATA) New York State Championship, and won! She won the ATA national championship for girls in 1944 and 1945. After losing in the women's final in 1946, she won her first of ten straight national ATA women's titles in 1947. She wrote that she knew she was a talented girl and wanted to prove it to her opponents.

Althea's success in the ATA caught the eye of Walter Johnson, a doctor from Lynchburg, Virginia. He was very active in the African American tennis community. Dr. Johnson helped Althea get better training and enter more important competitions. Later, he helped her get into the United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA, now USTA).

In 1946, she moved to Wilmington, North Carolina, with the help of another doctor and tennis supporter, Hubert A. Eaton. She enrolled at the Williston Industrial High School, which was a racially segregated school. In 1949, she became the first Black woman to play in the USTA's National Indoor Championships, reaching the quarter-finals. Later that year, she attended Florida A&M University (FAMU) on a full sports scholarship.

Amateur Tennis Career

Even though Althea was becoming a top player, she was not allowed to enter the biggest American tournament, the United States National Championships (now the US Open). While the rules didn't officially allow discrimination, players qualified by earning points at tournaments, and most of these were held at clubs that only allowed white members. In 1950, after a lot of effort from ATA officials and retired champion Alice Marble, Althea became the first Black player invited to the Nationals. She played her first match there a few days after her 23rd birthday.

She lost a close match in the second round to Louise Brough, who was the reigning Wimbledon champion. But her participation was big news everywhere. A journalist named Lester Rodney wrote that no Black player had ever played on those courts before. He said it was even tougher than what Jackie Robinson faced when he first played baseball for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

In 1951, Althea won her first international title, the Caribbean Championships in Jamaica. Later that year, she was one of the first Black players to compete at Wimbledon. In 1952, the USTA ranked her seventh nationally. In 1953, she graduated from Florida A&M and became a physical education teacher at Lincoln University.

In 1955, the State Department sent her on a special tour of Asia to play exhibition matches. People in countries like Burma, India, and Thailand felt a connection to Althea because she was a woman of color. They were happy to see her as part of an official US group. This six-week tour greatly boosted Althea's confidence. After the tour, she stayed abroad and won 16 out of 18 tournaments in Europe and Asia, beating many of the world's best players.

On May 27, 1956, Althea Gibson became the first African-American athlete to win a Grand Slam tournament. She won the singles event at the French Championships, beating Briton Angela Mortimer in the final. She also won the doubles title with her partner, Briton Angela Buxton. Later that year, she won the Wimbledon doubles championship (again with Buxton). She also won five tournaments in Italy, including the Italian Championships, and championships in India and Ceylon.

The year 1957 was "Althea Gibson's year," as she described it. In July, she was the top seed at Wimbledon, which was considered the "world championship of tennis." She defeated Darlene Hard in the finals to win the singles title. She was the first Black champion in the tournament's 80-year history. She also received the trophy directly from Queen Elizabeth II. Althea said that shaking hands with the Queen was a long way from being forced to sit in the "colored section" of the bus. She also won the doubles championship for the second year in a row.

When she returned home, Althea became only the second Black American, after Jesse Owens, to be honored with a ticker tape parade in New York City. Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. gave her the Bronze Medallion, the city's highest award for civilians. A month later, she won her first US National Championship. She wrote that winning Wimbledon was wonderful, but nothing felt quite like winning the championship of her own country. In 1957, she reached the finals of eight Grand Slam events, winning five of them. She also became the first Black player on the US Wightman Cup team, which won against Great Britain. Althea won her last 55 matches of 1957 and her first 2 matches in 1958, making it 57 wins in a row.

In 1958, Althea successfully defended her Wimbledon and US National singles titles. She also won her third straight Wimbledon doubles championship with a different partner. She was ranked the number-one woman in the United States and the world in both 1957 and 1958. The Associated Press named her Female Athlete of the Year in both years. She also became the first Black woman to appear on the covers of Sports Illustrated and Time magazines.

Professional Career

In late 1958, after winning 56 national and international titles, Althea Gibson stopped playing amateur tennis. Before the Open Era, there was no prize money at major tournaments, and players couldn't sign direct endorsement deals. They only received money for expenses. Althea wrote that her finances were in bad shape. She said being the "Queen of Tennis" was nice, but it didn't pay the bills. She had an "empty bank account" and couldn't fill it by playing amateur tennis.

Professional tours for women were still many years away, so her chances to earn money were limited to special events. In 1959, she played a series of exhibition matches against Karol Fageros before Harlem Globetrotter basketball games. After the tour, she won titles at the Pepsi Cola World Pro Tennis Championships, but only received $500 in prize money.

During this time, Althea also followed her dream of working in entertainment. She was a talented singer and saxophone player. She even came in second in a talent contest at the Apollo Theater in 1943. She made her professional singing debut in 1957. A record executive signed her to record an album of popular songs called Althea Gibson Sings, which came out in 1959. She performed two songs from it on The Ed Sullivan Show, but the album didn't sell well. She also appeared on a TV show called What's My Line? and acted in the movie The Horse Soldiers (1959). She refused to speak in a stereotypical way that the script asked for. She also worked as a sports commentator and appeared in ads. In 1960, her first book, I Always Wanted to Be Somebody, was published.

Her professional tennis career wasn't going well. She noticed that white tennis players, whom she had often beaten, were getting many offers. She realized that her victories had not completely removed the racial barriers as she had hoped. She also mentioned that she applied many times to be a member of the All-England Club (where Wimbledon is held) but was never accepted. Her doubles partner, Angela Buxton, who was Jewish, was also denied membership.

In 1964, at age 37, Althea became the first African-American woman to join the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) tour. Racial discrimination was still a problem. Many hotels did not allow people of color, and some golf clubs would not let her compete. When she did compete, she often had to change in her car because she was not allowed in the clubhouse. Even though she was one of the LPGA's top 50 money earners for five years, her total golf earnings were not very high.

Althea set course records in some individual rounds, but her highest ranking was 27th in 1966. Her best tournament finish was tying for second place in 1970. She retired from professional golf at the end of 1978. Golfer Judy Rankin said Althea could have been a great player if she had started golf when she was younger. She came along during a difficult time in golf and made a quiet difference.

After Retirement

In 1959, soon after retiring from tennis, Althea appeared in the film The Horse Soldiers. She played Lukey, a housekeeper. Her lines were originally written in a stereotypical way that Althea found offensive. She told the director, John Ford, that she would not say them as written. Even though Ford was known for not liking actors' demands, he agreed to change the script.

In 1968, when the Open Era began (allowing professional players to compete in major tournaments), Althea started entering big tennis tournaments again. However, by then she was in her forties and could not compete as well against younger players.

In 1972, Althea started running Pepsi Cola's national mobile tennis project. This program brought portable nets and equipment to less fortunate areas in big cities. She ran many other clinics and tennis programs for the next 30 years. She also coached many rising players, including Leslie Allen and Zina Garrison. Garrison wrote that Althea pushed her like a professional, not a junior, and that she owed her opportunities to Althea.

In the early 1970s, Althea began leading women's sports and recreation for the Essex County Parks Commission in New Jersey. In 1976, she was appointed New Jersey's athletic commissioner, becoming the first woman in the country to hold such a position. However, she resigned after one year because she didn't have enough control or funding. She said she didn't want to be just a "figurehead."

In 1976, Althea made it to the finals of the ABC television show Superstars. She finished first in basketball shooting and bowling, and second in softball throwing.

In 1977, Althea ran for State Senator in Essex County, New Jersey. She came in second. She then managed the Department of Recreation in East Orange, New Jersey. She also served on the State Athletic Control Board and became a supervisor for the Governor's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports.

Althea tried to make a comeback in golf in 1987, at age 60. Her goal was to be the oldest active tour player, but she couldn't get her tour card back. In her second book, So Much to Live For, she wrote about her disappointments, including dreams that didn't come true, few endorsement deals, and the many challenges she faced over the years.

Personal Life and Later Years

Althea Gibson married William Darben in 1965, but they divorced in 1976. In 1983, she married Sydney Llewellyn, who had been her coach during her best tennis years, but that marriage also ended in divorce. Althea Gibson did not have any children.

In the late 1980s, Althea's health started to get worse after she had two brain bleeds, followed by a stroke in 1992. Her medical bills became very high, causing her financial problems. She asked several tennis organizations for help but did not receive any. Her situation became known when her former doubles partner, Angela Buxton, told the tennis community about Althea's struggles. This led to nearly $1 million in donations from supporters around the world.

Althea survived a heart attack in 2003 but passed away on September 28 of that year due to complications from respiratory and bladder infections. She was buried in the Rosedale Cemetery, Orange, New Jersey, near her first husband, Will.

Legacy and Impact

It took 15 years for another non-White woman, Evonne Goolagong (an Australian Indigenous player), to win a Grand Slam championship in 1971. It was 43 years until another African-American woman, Serena Williams, won her first US Open in 1999. Serena's sister Venus then won back-to-back titles at Wimbledon and the US Open in 2000 and 2001, just like Althea did in 1957 and 1958.

Ten years after Althea's last win at the US Nationals, Arthur Ashe became the first African-American man to win a Grand Slam singles title at the 1968 US Open. Billie Jean King said that if it hadn't been for Althea, it wouldn't have been so easy for Arthur or the players who came after them.

In 1980, Althea Gibson was one of the first six people inducted into the International Women's Sports Hall of Fame. This placed her alongside famous pioneers like Amelia Earhart and Wilma Rudolph. She was also inducted into many other halls of fame, including the International Tennis Hall of Fame and the National Women's Hall of Fame. In 1988, she received a Candace Award.

In 1991, Althea became the first woman to receive the Theodore Roosevelt Award, the highest honor from the National Collegiate Athletic Association. She was recognized for showing the best qualities of competitive excellence and good sportsmanship. She was also honored for helping to create more opportunities for women and minorities in sports. Sports Illustrated for Women included her on its list of the "100 Greatest Female Athletes."

In 1977, a writer for The New York Times, William C. Rhoden, wrote that Althea Gibson and Wilma Rudolph were the most important Black women in sports history. He said that while Wilma's achievements made women athletes more visible, Althea's achievements were more "revolutionary." Her victories, like Jackie Robinson's in baseball, proved that Black people could compete at any level in American society when given a chance.

On the opening night of the 2007 US Open, which was 50 years after her first victory at the US National Championships, Althea Gibson was honored in the US Open Court of Champions. USTA president Alan Schwartz said that Althea's quiet strength during the challenging 1950s was truly remarkable. He added that her legacy lives on in stadiums, schools, and parks. He noted that when she started playing, less than five percent of new tennis players were minorities. Today, about 30 percent are minorities, and two-thirds of those are African American. This is her legacy.

Althea Gibson's five Wimbledon trophies are displayed at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History. The Althea Gibson Cup, a tournament for older players, is held every year in Croatia. The Althea Gibson Foundation helps talented golf and tennis players who live in cities. In 2005, her friend Bill Cosby created the Althea Gibson Scholarship at her old university, Florida A&M University.

In September 2009, Wilmington, North Carolina, named its new community tennis court facility the Althea Gibson Tennis Complex. Other tennis facilities named after her include those at Manning High School (near her birthplace) and Florida A&M University.

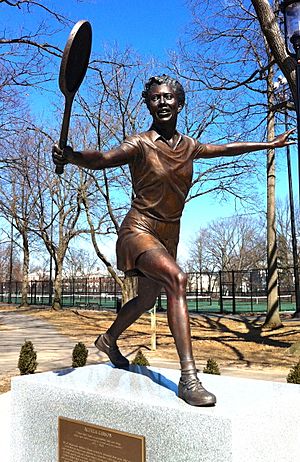

In 2012, a bronze statue of Althea, created by sculptor Thomas Jay Warren, was placed in Branch Brook Park in Newark, New Jersey. It is near the courts where she ran clinics for young players.

In August 2013, the United States Postal Service released a postage stamp honoring Althea Gibson. A documentary called Althea was shown on PBS in September 2015. In November 2017, Paris, France, opened a public sports center named Gymnase Althea Gibson. Althea Gibson will also be honored on a U.S. quarter coin in 2025.

In 2018, the USTA decided to build a statue honoring Althea at Flushing Meadows, where the US Open is held. The statue, created by Eric Goulder, was unveiled in 2019. It is only the second monument there honoring a champion. Goulder said that Althea changed the world and how we see what is possible.

In her 1958 retirement speech, Althea said she hoped she had achieved one thing: to be a credit to tennis and to her country. The inscription on her Newark statue says, "By all measures, Althea Gibson certainly attained that goal."

Why is Althea Gibson an American hero?

Althea Gibson was an American hero because she was a groundbreaking athlete who bravely broke down racial barriers in the world of sports, especially in tennis and golf. She was the first African American person to win major championships in these sports, showing incredible talent, determination, and courage that inspired countless people and helped change how society viewed athletes of color.

Grand Slam Finals

Singles: 7 (5 titles, 2 runner-ups)

| Result | Year | Tournament | Surface | Opponent | Score | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | 1956 | French Championships | Clay | 6–0, 12–10 | ||

| Loss | 1956 | US Championships | Grass | 3–6, 4–6 | ||

| Loss | 1957 | Australian Championships | Grass | 3–6, 4–6 | ||

| Win | 1957 | Wimbledon | Grass | 6–3, 6–2 | ||

| Win | 1957 | US Championships | Grass | 6–3, 6–2 | ||

| Win | 1958 | Wimbledon (2) | Grass | 8–6, 6–2 | ||

| Win | 1958 | US Championships (2) | Grass | 3–6, 6–1, 6–2 |

Key: (#) denotes her number of singles titles at the tournament at the time.

Doubles: 7 (5 titles, 2 runner-ups)

| Result | Year | Tournament | Surface | Partner | Opponents | Score | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | 1956 | French Championships | Clay | 6–8, 8–6, 6–1 | |||

| Win | 1956 | Wimbledon | Grass | 6–1, 8–6 | |||

| Win | 1957 | Australian Championships | Grass | 6–2, 6–1 | |||

| Win | 1957 | Wimbledon (2) | Grass | 6–1, 6–2 | |||

| Loss | 1957 | US Championships | Grass | 2–6, 5–7 | |||

| Win | 1958 | Wimbledon (3) | Grass | 6–3, 7–5 | |||

| Loss | 1958 | US Championships | Grass | 6–2, 3–6, 4–6 |

Key: (#) denotes her number of doubles titles at the tournament at the time.

Mixed Doubles: 4 (1 title, 3 runner-ups)

| Result | Year | Tournament | Surface | Partner | Opponents | Score | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss | 1956 | Wimbledon | Grass | 6–2, 2–6, 5–7 | |||

| Loss | 1957 | Wimbledon | Grass | 4–6, 5–7 | |||

| Win | 1957 | US Championships | Grass | 6–3, 9–7 | |||

| Loss | 1958 | Wimbledon | Grass | 3–6, 11–13 |

Grand Slam Tournament Performance Timeline

| W | F | SF | QF | #R | RR | Q# | A | NH |

Singles

| Tournament | 1950 | 1951 | 1952 | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | SR | W–L | Win % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australian Championships | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | F | A | 0 / 1 | 4–1 | 80% |

| French Championships | A | A | A | A | A | A | W | A | A | 1 / 1 | 6–0 | 100% |

| Wimbledon Championships | A | 3R | A | A | A | A | QF | W | W | 2 / 4 | 17–2 | 89% |

| US Championships | 2R | 3R | 3R | QF | 1R | 3R | F | W | W | 2 / 9 | 27–7 | 79% |

| Win–loss | 1–1 | 3–2 | 2–1 | 3–1 | 0–1 | 2–1 | 15–2 | 16–1 | 12–0 | 5 / 15 | 54–10 | 84% |

Source:

See also

In Spanish: Althea Gibson para niños

In Spanish: Althea Gibson para niños

- List of African American firsts

- Performance timelines for all female tennis players who reached at least one Grand Slam final

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |